The Legal Implications of Underbelly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg Mclean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS

A Stan Original Series presents A Screentime, a Banijay Group company, production, in association with Emu Creek Pictures financed with the assistance of Screen Australia and the South Australian Film Corporation Based on the feature films WOLF CREEK written, directed and produced by Greg McLean Adapted for television by Peter Gawler, Greg McLean & Felicity Packard Production Notes Greg Haddrick, Greg McLean Nick Forward, Rob Gibson, Jo Rooney, Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Felicity Packard SERIES WRITERS Tony Tilse & Greg McLean SERIES DIRECTORS As at 2.3.16 As at 2.3.16 TABLE OF CONTENTS Key Cast Page 3 Production Information Page 4 About Stan. and About Screentime Page 5 Series Synopsis Page 6 Episode Synopses Pages 7 to 12 Select Cast Biographies & Character Descriptors Pages 15 to 33 Key Crew Biographies Pages 36 to 44 Select Production Interviews Pages 46 to 62 2 KEY CAST JOHN JARRATT Mick Taylor LUCY FRY Eve Thorogood DUSTIN CLARE Detective Sergeant Sullivan Hill and in Alphabetical Order EDDIE BAROO Ginger Jurkewitz CAMERON CAULFIELD Ross Thorogood RICHARD CAWTHORNE Kane Jurkewitz JACK CHARLES Uncle Paddy LIANA CORNELL Ann-Marie RHONDDA FINDELTON Deborah ALICIA GARDINER Senior Constable Janine Howard RACHEL HOUSE Ruth FLETCHER HUMPHRYS Jesus (Ben Mitchell) MATT LEVETT Kevin DEBORAH MAILMAN Bernadette JAKE RYAN Johnny the Convict MAYA STANGE Ingrid Thorogood GARY SWEET Jason MIRANDA TAPSELL Constable Fatima Johnson ROBERT TAYLOR Roland Thorogood JESSICA TOVEY Kirsty Hill 3 PRODUCTION INFORMATION Title: WOLF CREEK Format: 6 X 1 Hour Drama Series Logline: Mick Taylor returns to wreak havoc in WOLF CREEK. -

VIEW from the BRIDGE Marco Melbourne Theatre Company Dir: Iain Sinclair

sue barnett & associates DAMIAN WALSHE-HOWLING AWARDS 2011 A Night of Horror International Film Festival – Best Male Actor – THE REEF 2009 Silver Logie Nomination – Most Outstanding Actor – UNDERBELLY 2008 AFI Award Winner – Best Guest or Supporting Actor in a Television Drama – UNDERBELLY 2001 AFI Award Nomination – Best Actor in a Guest Role in a Television Series – THE SECRET LIFE OF US FILM 2021 SHAME John Kolt Shame Movie Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Major 2018 2067 Billy Mitchell Arcadia/Kojo Entertainment Dir: Seth Larney DESERT DASH (Short) Ivan Ralf Films Dir: Gracie Otto 2014 GOODNIGHT SWEETHEART (Short) Tyson Elephant Stamp Dir: Rebecca Peniston-Bird 2012 MYSTERY ROAD Wayne Mystery Road Films Pty Ltd Dir: Ivan Sen AROUND THE BLOCK Mr Brent Graham Around the Block Pty Ltd Dir; Sarah Spillane THE SUMMER SUIT (Short) Dad Renegade Films 2011 MONKEYS (Short) Blue Tongue Films Dir: Joel Edgerton POST APOCALYPTIC MAN (Short) Shade Dir: Nathan Phillips 2009 THE REEF Luke Prodigy Movies Pty Ltd Dir: Andrew Traucki THE CLEARING (Short) Adam Chaotic Pictures Dir: Seth Larney 2006 MACBETH (M) Ross Mushroom Pictures Dir: Geoffrey Wright 2003 JOSH JARMAN Actor Prod: Eva Orner Dir: Pip Mushin 2002 NED KELLY Glenrowan Policeman Our Sunshine P/L Dir: Gregor Jordan 2001 MINALA Dan Yirandi Productions Ltd Dir: Jean Pierre Mignon 1999 HE DIED WITH A FELAFEL IN HIS HAND Milo Notorious Films Dir: Richard Lowenstein 1998 A WRECK A TANGLE Benjamin Rectango Pty Ltd Dir: Scott Patterson TELEVISION 2021 JACK IRISH (Series 3) Daryl Riley ABC TV Dir: Greg McLean -

Official Committee Hansard

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Official Committee Hansard JOINT COMMITTEE ON THE AUSTRALIAN CRIME COMMISSION Reference: Legislative arrangements to outlaw serious and organised crime groups THURSDAY, 3 JULY 2008 ADELAIDE BY AUTHORITY OF THE PARLIAMENT INTERNET Hansard transcripts of public hearings are made available on the inter- net when authorised by the committee. The internet address is: http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard To search the parliamentary database, go to: http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au JOINT STATUTORY COMMITTEE ON AUSTRALIAN CRIME COMMISSION Thursday, 3 July 2008 Members: Senator Hutchins (Chair), Mr Wood (Deputy Chair), Senators Barnett, Parry and Polley and Mr Champion, Mr Gibbons, Mr Hayes and Mr Pyne Members in attendance: Senators Barnett, Hutchins and Parry and Mr Champion, Mr Gibbons, Mr Hayes, Mr Pyne and Mr Wood Terms of reference for the inquiry: To inquire into and report on: The effectiveness of legislative efforts to disrupt and dismantle serious and organised crime groups and associations with these groups, with particular reference to: a. international legislative arrangements developed to outlaw serious and organised crime groups and association to those groups, and the effectiveness of these arrangements; b. the need in Australia to have legislation to outlaw specific groups known to undertake criminal activities, and membership of and association with those groups; c. Australian legislative arrangements developed to target consorting for criminal activity and to outlaw serious and organised crime groups, and membership of and association with those groups, and the effectiveness of these arrangements; d. the impact and consequences of legislative attempts to outlaw serious and organised crime groups, and membership of and association with these groups on: i. -

Qatar, France Sign Pact for Strategic Dialogue

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Czech star Pliskova takes tough Vodafone Qatar schedule in posts QR118mn profi t in 2018 her stride published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXIX No. 11092 February 12, 2019 Jumada II 7, 1440 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Amir meets French FM Amir honours winners of state awards His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani honoured winners of the Qatar’s appreciative and incentive state awards in sciences, arts and literature. His Highness the Amir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani met with French Minister The award winners were Dr Abdulaziz bin Abdullah Turki al-Subaie in the field of education, Mohamed Jassim al-Khulaifi (museums and archaeology), Dr Saif Saeed of Europe and Foreign Aff airs Jean-Yves Le Drian and his accompanying delegation Saif al-Suwaidi (economics), Dr Yousif Mohamed Yousif al-Obaidan (political science), Dr Hamad Abdulrahman al-Saad al-Kuwari (earth and environmental sciences), at the Amiri Diwan yesterday. The minister conveyed to the Amir the congratulations Mohanna Rashid al-Asiri al-Maadeed (earth and environmental sciences), Dr Huda Mohamed Abdullatif al-Nuaimi (allied medical sciences and nursing), Dr Asma of French President Emmanuel Macron on Qatar national football team winning the Ali Jassim al-Thani (allied medical sciences and nursing), Salman Ibrahim Sulaiman al-Malik (the art of caricature) and Abdulaziz Ibrahim al-Mahmoud in the novel 2019 Asian Cup. During the meeting, they reviewed bilateral relations and means of field. The Amir commended the winners’ distinguished performance, wishing them success in rendering services to the homeland. -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 01/12/2012 A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra ABB V.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.1 ABB V.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.2 ABB V.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.3 ABB V.4 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Schmidt ABO Above the rim ACC Accepted ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam‟s Rib ADA Adaptation ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes‟ smarter brother, The AEO Aeon Flux AFF Affair to remember, An AFR African Queen, The AFT After the sunset AFT After the wedding AGU Aguirre : the wrath of God AIR Air Force One AIR Air I breathe, The AIR Airplane! AIR Airport : Terminal Pack [Original, 1975, 1977 & 1979] ALA Alamar ALE Alexander‟s ragtime band ALI Ali ALI Alice Adams ALI Alice in Wonderland ALI Alien ALI Alien vs. Predator ALI Alien resurrection ALI3 Alien 3 ALI Alive ALL All about Eve ALL All about Steve ALL series 1 All creatures great and small : complete series 1 ALL series 2 All creatures great and small : complete series 2 ALL series 3 All creatures great and small : complete series 3 *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ALL series 4 All creatures great -

Walpole Public Library DVD List A

Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] Last updated: 9/17/2021 INDEX Note: List does not reflect items lost or removed from collection A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nonfiction A A A place in the sun AAL Aaltra AAR Aardvark The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.1 vol.1 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.2 vol.2 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.3 vol.3 The best of Bud Abbot and Lou Costello : the Franchise Collection, ABB V.4 vol.4 ABE Aberdeen ABO About a boy ABO About Elly ABO About Schmidt ABO About time ABO Above the rim ABR Abraham Lincoln vampire hunter ABS Absolutely anything ABS Absolutely fabulous : the movie ACC Acceptable risk ACC Accepted ACC Accountant, The ACC SER. Accused : series 1 & 2 1 & 2 ACE Ace in the hole ACE Ace Ventura pet detective ACR Across the universe ACT Act of valor ACT Acts of vengeance ADA Adam's apples ADA Adams chronicles, The ADA Adam ADA Adam’s Rib ADA Adaptation ADA Ad Astra ADJ Adjustment Bureau, The *does not reflect missing materials or those being mended Walpole Public Library DVD List [Items purchased to present*] ADM Admission ADO Adopt a highway ADR Adrift ADU Adult world ADV Adventure of Sherlock Holmes’ smarter brother, The ADV The adventures of Baron Munchausen ADV Adverse AEO Aeon Flux AFF SEAS.1 Affair, The : season 1 AFF SEAS.2 Affair, The : season 2 AFF SEAS.3 Affair, The : season 3 AFF SEAS.4 Affair, The : season 4 AFF SEAS.5 Affair, -

Fat Tony__Co Final D

A SCREENTIME production for the NINE NETWORK Production Notes Des Monaghan, Greg Haddrick Jo Rooney & Andy Ryan EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS Peter Gawler & Elisa Argenzio PRODUCERS Peter Gawler, Adam Todd, Jeff Truman & Michaeley O’Brien SERIES WRITERS Peter Andrikidis, Andrew Prowse & Karl Zwicky SERIES DIRECTORS MEDIA ENQUIRIES Michelle Stamper: NINE NETWORK T: 61 3 9420 3455 M: 61 (0)413 117 711 E: [email protected] IMPORTANT LEGAL NOTIFICATION TO MEDIA Screentime would like to remind anyone reporting on/reviewing the mini-series entitled FAT TONY & CO. that, given its subject matter, the series is complicated from a legal perspective. Potential legal issues include defamation, contempt of court and witness protection/name suppression. Accordingly there are some matters/questions that you may raise which we shall not be in a position to answer. In any event, please note that it is your responsibility to take into consideration all such legal issues in determining what is appropriate for you/the company who employs you (the “Company”) to publish or broadcast. Table of Contents Synopsis…………………………………………..………..……………………....Page 3 Key Players………….…………..…………………….…….…..……….....Pages 4 to 6 Production Facts…………………..…………………..………................Pages 7 to 8 About Screentime……………..…………………..…….………………………Page 9 Select Production & Cast Interviews……………………….…….…Pages 10 to 42 Key Crew Biographies……………………………………………...….Pages 43 to 51 Principal & Select Supporting Cast List..………………………………...….Page 52 Select Cast Biographies…………………………………………….....Pages 53 to 69 Episode Synopses………………………….………………….………..Pages 70 to 72 © 2013 Screentime Pty Ltd and Nine Films & Television Pty Ltd 2 SYNOPSIS FAT TONY & CO., the brand-new production from Screentime, tells the story of Australia’s most successful drug baron, from the day he quit cooking pizza in favour of cooking drugs, to the heyday of his $140 million dollar drug empire, all the way through to his arrest in an Athens café and his whopping 22-year sentence in Victoria’s maximum security prison. -

PDF Download Gangland Melbourne Ebook, Epub

GANGLAND MELBOURNE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Morton | 208 pages | 01 Oct 2011 | Melbourne University Press | 9780522858693 | English | Carlton, Australia Gangland Melbourne PDF Book EU leaders to discuss plans to roll-out Covid vaccine passports - while Britons who have received jabs will Ordinary Australians are being fined extortionate amounts for doing regular things like exercising outside for too long. News Home. Medical emergency involving flight crew member forces Virgin plane to return to Adelaide Posted 5 h hours ago Fri Friday 15 Jan January at am. Scottish Tories suspend candidate who claimed 'fat' foodbank users are 'far from starving' and accused Rebel Roundup Every Friday. The world's most popular perfume revealed: Carolina Herrerra's Good Girl is the most in demand across the Many of the murders remain unsolved, although detectives from the Purana Taskforce believe that Carl Williams was responsible for at least 10 of them. In the wake of the Informer scandal, Williams believed she could still get back the Primrose Street property, which was seized to repay her family's tax debt. May 8, - Lewis Caine, a convicted killer who had changed his name to Sean Vincent, shot dead and his body dumped in a back street in Brunswick. Never-before-seen photos of the St Kilda murder scene of an underworld figure have been released as part of a renewed police push for answers over the major event in the early years of Melbourne's gangland war. It is not allowed to happen,' she said. Boris Johnson and the Two Ronnies could be replaced by An edited version commenced screening in Victoria on 14 September Investigation concludes Joe the pigeon had a fake US leg band and won't be executed. -

Sue Barnett & Associates

sue barnett & associates AARON JEFFERY TRAINING Graduate of the National Institute of Dramatic Art, 1993 FILM MOONROCK FOR MONDAY Bob Lunar Productions Dir: Kurt Martin THE FLOOD Mitch Harvest Pictures/Redman Entertainments Dir: Victoria Wharfe McIntyre PALM BEACH Doug Soapbox Industries Dir: Rachel Ward OCCUPATION Major Davis Sparke Films Dir: Luke Sparke RIP TIDE Owen The Steve Jaggi Company Dir: Rhiannon Bannenberg TURBO KID Frederic T&A Films Dir: Jason Eisner LOCKS OF LOVE: A FAMILIAR FEELING Terry Knox ScreenACT Dir: Adele Morey X-MEN ORIGINS: WOLVERINE Thomas Logan Wolverine Films Pty Ltd Dir: Gavin Hood BEAUTIFUL Alan Hobson Kojo Pictures Dir. Dean O’Flaherty STRANGE PLANET Joel Strange Planet Productions Dir: Emma Kate Croghan THE INTERVIEW Prior Interview Films P/L Dir: Craig Monaghan CARCRASH Narrator Binnaburra Film Corp. SQUARE ONE Jeremy Hostick Arcadia Pictures GOOD FRUIT Sharman Mezmo Pictures Dir: William Osack TELEVISION BETWEEN TWO WORLDS David Baines Seven Network Dir: Various UNDERBELLY FILES: CHOPPER Chopper Read Screentime Dir: Peter Andrikidis BLUE MURDER: KILLER COP (Mini-series) Chris Bronowski Endemol Shine Dir: Michael Jenkins JANET KING (Series 2) Simon Hamilton Screentime Dir: Peter Andrikidis/Grant Brown TEXAS RISING Ranger History Channel WENTWORTH (Series 3) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin Carlin WENTWORTH (Series 2) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin Carlin OLD SCHOOL Rick Matchbox Pictures Dir: Gregor Jordan WENTWORTH (Series 1) Matt Fletcher FremantleMedia/Foxtel Dir: Kevin -

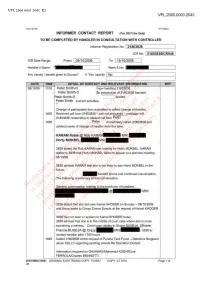

Redactions Have Been Applied by the Royal Commission in This Document

VPL.2000.0003.2043_R2 VPL.2000.0003.2043 New 07/05 VP1092A INFORMER CONTACT REPORT (For DSU Use Only) TO BE COMPLETED BY HANDLER IN CONSULTATION WITH CONTROLLER Informer Registration No: | 21803838 | ICR No: I 21803838ICR048 | ICR Date Range From: | 09/10/2006 | To: I 15/10/2006 | Handler’s Name: Rank & No: Any money! benefit given to Source? If ‘Yes’ specify No DATE TIME DETAIL OF CONTACT AND RELEVANT INFORMATION REF 09/10/06 1315 Peter Smith-0 | now handling 21803838. Peter Smith-0 |in possession ofCommission 21803838 handset. Peter Smith-0 _ _ _______ briefed Peter Smith Current activities. it including, Royal Change of participants form submitted to reflect changelegal of handler. 1405 Received call from 21803838 -the call not answered - message left. 21803838 responding to missed call from Peter 1405 byPeter reasonsimmediately called 21803838 and advised same of change of handler from this time. determined of immunity,non-publication KARAM Rabie @ Rob KARAM^^^Mof has legislative, Horty MOKBEL^^Happlied mNI^^^H numberinterest 3838 beenstated the a Rob KARAM was looking for Horty MOKBEL. KARAM stated to 3838 that Horty MOKBEL failed to appear at a planned meeting 08/10/06.for operation have public Commissionreputational, 3838 advisedto, KARAM that she is not likely to see Horty MOKBEL in the future. ________the on privilege, handed phone and continued conversation. documentThe following a summary of that conversation. limited wherebased reasons. Redactionsthis General conversation relating to the handover of handlers. not in and @ M N1: but safety professional3838 stated thator she last saw Kamel KHODER on Sunday - 08/10/2006 orders,andappropriate drove same to Crispy Creme Donuts at the request of Kamel KHODER. -

New York City Council Bans N-Word

INTERNATIONAL CHINA DAILY FRIDAY MARCH 2, 20079 WORLDSCENE New York city council bans N-word UNITED STATES councillor who proposed the reso- ment right to free speech, Richards come to be seen by many as the most ‘Old Man’ of mafi a’s guilty plea Black screenwriters and rappers urged lution, has called on the academy said, pointing to the supreme court’s offensive racial slur in English. A 96-year-old gangster who oversaw which runs the Grammy awards decision to uphold the right to burn Roy Miller, a lawyer from Atlanta, robberies, money laundering, bank to rein back use of racist term following to withhold nominations from acts the American fl ag, and its ruling that Georgia, was invited to speak to a fraud and other crimes for one of using it. At the awards last month, a man resisting military conscription committee of the New York council the largest mafi a families in the councillors unanimous vote for crackdown artists such as Ludacris and Chamil- had the right to wear a jacket in court when it debated the resolution on US pleaded guilty yesterday, but lionaire were honored for songs which saying “fuck the draft”. Monday. The civil rights committee because of his age will probably be ew York banned the word mon use of the word, especially in contained the term. Marcia Williams, of the campaign- voted by fi ve to none to pass the reso- sentenced to house arrest. nigger yesterday in a the black community, where it has ing website Ban the N-word, said that lution imposing a moratorium. -

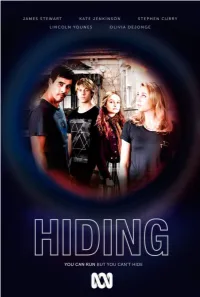

Hiding Media Kit.Pdf

YOU CAN RUN BUT YOU CAN’T HIDE PREMIERES THURSDAY 5 FEBRUARY 8.30PM You can change your job, your city, your identity, but some things you can A bureaucratic bungle lands Mitchell (Lincoln Younes) and Tara (Olivia DeJonge) never escape. And they could cost Troy Quigg and his family their lives in the in a performing arts school. While it’s a happy outcome for aspirational uniquely gripping, family drama series, HIDING. fifteen year-old Tara, it’s torture for seventeen year-old surfer, Lincoln, who is desperate to get his old life back, especially his gorgeous girlfriend, Kelly After a botched drug deal, Troy (James Stewart) must take his family into (Jenna Kratzel). Adding to the teenager’s torment, no phones or Facebook, Witness Protection in exchange for giving evidence against his former no texts or twitter. Because a trace could bring a killer to their door. employer, vicious crime boss Nils Vandenberg (Marcus Graham). As the dysfunctional Swift family adjusts to their new world living with constant With new names and fresh identities, the Quigg family is ripped from their threat of corrupt cops or a leak within Witness Protection, a surprise phone home on the sun-drenched Gold Coast and dumped in a safe house in call unleashes an emotional upheaval that could crack their cover and bring Western Sydney as the Swift Family. But dislocation puts immense pressure those who want Lincoln silenced gunning for him and those he loves. on everyone. HIDING delivers a unique blend of humour and tension in this high stakes Lincoln Swift’s cover as a post-doctorate fellow in the Criminal Psychology family drama.