211 Interpretation of C Ulturec Ontact Atc Olonyr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOSE LUIZ E JOSE AUGUSTO.P65

CÂNDIDO DE MELLO LEITÃO FRANCO, José Luiz de Andrade; DRUMMOND, José Augusto. Cândido de Mello Leitão: as ciências biológicas e a Cândido de Mello valorização da natureza e da diversidade da vida. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, Leitão: as ciências Rio de Janeiro, v.14, n.4, p.1265-1290, out.-dez. 2007. biológicas Examina o pensamento do zoólogo brasileiro Cândido de Mello Leitão (1886-1948). Explora aspectos do seu pensamento e a valorização relacionados à preocupação com a valorização do conhecimento científico e da da natureza e da natureza em toda a sua diversidade. Destaca episódios relevantes de sua biografia pessoal diversidade da vida e profissional, bem como analisa parte de sua produção bibliográfica, publicada entre 1935 e 1947. Mello Leitão afirmava a necessidade de um processo civilizador que reconciliasse o homem e o mundo natural, processo no Cândido de Mello qual ciência e Estado teriam responsabilidades a compartilhar, sobretudo no Brasil, país que Leitão: the biological ele considerava estar em busca de identidade nacional e de um modelo de civilização. sciences and the PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Cândido de Mello Leitão; conservação da natureza; Museu Nacional do Rio de Janeiro; história da valorization of nature ciência; fauna selvagem; zoogeografia. and diversity of life FRANCO, José Luiz de Andrade; DRUMMOND, José Augusto. Cândido de Mello Leitão: the biological sciences and the valorization of nature and diversity of life . História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, Rio de Janeiro, v.14, n.4, p.1265-1290, Oct.-Dec. 2007. This exploration of the thought of Brazilian zoologist Cândido de Mello Leitão (1886-1948) concentrates on his concern with valuing scientific knowledge and nature in all its diversity. -

The Brazilian Campos in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Art

The Brazilian Campos in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Art André S. Bailão Summary The mosaic of tropical grasslands, savannahs, and woodlands in the Brazilian Highlands, commonly called campos in the early nineteenth century and Cerrado nowadays, was depicted by European traveling artists and naturalists following new modes of visualization in arts and sciences, in dialogue with Alexander von Humboldt. Illustrations in travel albums presented landscapes following sensorial experiences from the journeys and physiognomic and phytogeographic features studied in the field. They document the transformations of the territory by the advancing settler colonization, with a strong focus on cattle ranching, hunting, and burning of the grasslands. Traveling naturalists and artists took advantage of the opening of Brazilian borders in 1808 by the Portuguese Crown, which moved to Rio de Janeiro during the Napoleonic Wars. They were interested in describing, botanizing, and collecting in a country that remained mostly unknown outside the Portuguese Empire. Most travelers remained on the coast, especially in Rio de Janeiro, which resulted in multiple accounts and images of the surrounding rainforests and coastal landscapes. The inner Highlands (planalto) of Central Brazil were more difficult to reach due to long distances and travel conditions but some visited the mining districts, where the coastal rainforests (Mata Atlântica) change into drier vegetations as people advance towards the interior. Bailão, André S. “The Brazilian Campos in Nineteenth-Century Landscape Art.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2021), no. 15. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9279. Print date: 07 June 2021 17:37:06 Map of the Cerrado ecoregion as delineated by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF). -

A Publisher and an Antique Dealer for Most of His Life, Streeter Blair (1888–1966) Began Painting at the Age of 61 in 1949

1960 Paintings by Streeter Blair (January 12–February 7) A publisher and an antique dealer for most of his life, Streeter Blair (1888–1966) began painting at the age of 61 in 1949. Blair became quite successful in a short amount of time with numerous exhibitions across the United States and Europe, including several one-man shows as early as 1951. He sought to recapture “those social and business customs which ended when motor cars became common in 1912, changing the life of America’s activities” in his artwork. He believed future generations should have a chance to visually examine a period in the United States before drastic technological change. This exhibition displayed twenty-one of his paintings and was well received by the public. Three of his paintings, the Eisenhower Farm loaned by Mr. & Mrs. George Walker, Bread Basket loaned by Mr. Peter Walker, and Highland Farm loaned by Miss Helen Moore, were sold during the exhibition. [Newsletter, memo, various letters] The Private World of Pablo Picasso (January 15–February 7) A notable exhibition of paintings, drawings, and graphics by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), accompanied by photographs of Picasso by Life photographer, David Douglas Duncan (1916– 2018). Over thirty pieces were exhibited dating from 1900 to 1956 representing Picasso’s Lautrec, Cubist, Classic, and Guernica periods. These pieces supplemented the 181 Duncan photographs, shown through the arrangement of the American Federation of Art. The selected photographs were from the book of the same title by Duncan and were the first ever taken of Picasso in his home and studio. -

VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, and COLONIALISM on the NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA a THESIS Pres

“OUR PEOPLE SCATTERED:” VIOLENCE, CAPTIVITY, AND COLONIALISM ON THE NORTHWEST COAST, 1774-1846 by IAN S. URREA A THESIS Presented to the University of Oregon History Department and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Ian S. Urrea Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the History Department by: Jeffrey Ostler Chairperson Ryan Jones Member Brett Rushforth Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded September 2019 ii © 2019 Ian S. Urrea iii THESIS ABSTRACT Ian S. Urrea Master of Arts University of Oregon History Department September 2019 Title: “Our People Scattered:” Violence, Captivity, and Colonialism on the Northwest Coast, 1774-1846” This thesis interrogates the practice, economy, and sociopolitics of slavery and captivity among Indigenous peoples and Euro-American colonizers on the Northwest Coast of North America from 1774-1846. Through the use of secondary and primary source materials, including the private journals of fur traders, oral histories, and anthropological analyses, this project has found that with the advent of the maritime fur trade and its subsequent evolution into a land-based fur trading economy, prolonged interactions between Euro-American agents and Indigenous peoples fundamentally altered the economy and practice of Native slavery on the Northwest Coast. -

José Bonifácio, Primeiro Chanceler Do Brasil MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES

José Bonifácio, primeiro Chanceler do Brasil MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES Ministro de Estado Embaixador Celso Amorim Secretário-Geral Embaixador Samuel Pinheiro Guimarães FUNDAÇÃO ALEXANDRE DE GUSMÃO Presidente Embaixador Jeronimo Moscardo INSTITUTO RIO BRANCO (IRBr) Diretor Embaixador Fernando Guimarães Reis A Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão, instituída em 1971, é uma fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério das Relações Exteriores e tem a finalidade de levar à sociedade civil informações sobre a realidade internacional e sobre aspectos da pauta diplomática brasileira. Sua missão é promover a sensibilização da opinião pública nacional para os temas de relações internacionais e para a política externa brasileira. Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo, Sala 1 70170-900 Brasília, DF Telefones: (61) 3411 6033/6034/6847 Fax: (61) 3411 9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br João Alfredo dos Anjos José Bonifácio, primeiro Chanceler do Brasil Brasília, 2008 Direitos de publicação reservados à Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo 70170-900 Brasília – DF Telefones: (61) 3411 6033/6034/6847/6028 Fax: (61) 3411 9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br E-mail: [email protected] Capa: Coroação de D. Pedro I pelo Bispo do Rio de Janeiro, Monsenhor José Caetano da Silva Coutinho, no dia 1º de dezembro de 1822, na Capela do Paço Imperial. 1828, Rio de Janeiro. Óleo sobre tela, 340x640cm Doação do Embaixador Assis Chateaubriand. Equipe Técnica Coordenação: Eliane Miranda Paiva Programação Visual e Diagramação: Cláudia Capella e Paulo Pedersolli Originalmente apresentado como tese do autor no LII CAE, Instituto Rio Branco, 2007. -

Coleção E Circulação Da Produção Visual De Maria Graham

Viajar, observar e registrar: coleção e circulação da produção visual de Maria Graham Traveling, observing and recording: collection and circulation of Maria Graham's visual production Maria de Fátima Medeiros de Souza Como citar: SOUZA, M. de F. M. de. Viajar, observar e registrar: Coleção e circulação da produção visual de Maria Graham. MODOS: Revista de História da Arte, Campinas, SP, v. 5, n. 2, p. 59–85, 2021. DOI: 10.20396/modos.v5i2.8664763. Disponível em: https://periodicos. sbu.unicamp.br/ojs/index.php/mod/article/view/8664763. Imagem: Maria Graham. Aristolachia. Aquarela, s/d. Fonte: Library, Art & Archives, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Viajar, observar e registrar: coleção e circulação da produção visual de Maria Graham Traveling, observing and recording: collection and circulation of Maria Graham's visual production Maria de Fátima Medeiros de Souza* Resumo A produção visual de Maria Graham se relaciona com as redes de sociabilidade estabelecidas com naturalistas, colecionadores, viajantes, artistas e antiquarianistas. Os acervos da viajante britânica indicam negociações com editores de seus livros de viagem, aspectos da configuração das ilustrações dos livros, assim como trocas de coleções naturais e de informações sobre a paisagem e a flora brasileira. Graham viajou por países como Índia, Brasil, Chile e Itália, e publicou diários sobre esses percursos. Paralela à escrita dos livros, ela produzia cadernos de viagens e ilustrações científicas que ainda são pouco conhecidos e estudados pela literatura especializada. Como uma das poucas mulheres de seu tempo a se destacar na literatura de viagem e a possuir um trabalho botânico consistente, a trajetória de Graham mostra como as mulheres se articularam com figuras chave nas artes e nas ciências. -

O Imperador Do Brasil E Os Seus Amigos Da Nova-Inglaterra

O IMPERADOR DO BRASIL E OS SEUS AMIGOS DA NOVA-INGLATERRA Explicação Apresenta o Museu Imperial, neste número de seu Anuário, um trabalho do prof. David James, acerca das relações entre d. Pedro II e os seus amigos da Norte América. Não é a primeira vez que honra o prof. James as páginas desta publicação. No volume referente a 1946 apresentou ele erudito e interessante estudo sabre o pintor francês Raymond Quinsac Monvoisin, artista ligado à arte brasileira do Segundo Reinado, tendo, nessa oportunidade, a colaboração do sr. Francisco Marques dos Santos, profundo conhecedor de nossa história, e cuja sempre solicitada e nunca negada cooperação foi, mais uma vez, posta à prova. Vem agora o prof. James trazer-nos o resultado de suas laboriosas pesquisas em arquivos nacionais e estrangeiros, avultando entre aqueles a preciosa coleção de documentos da família imperial brasileira, agora incorporada ao patrimônio deste museu. As relações entre o imperador e os sábios estrangeiros não é assunto inédito no Anuário. Já no volume VIII, referente a 1947, foi publicado um substancioso estudo sobre o tema, intitulado: “Dom Pedro II e os intelectuais portugueses”, de autoria do saudoso diretor desta casa, Alcindo Sodré. O trabalho do prof. David James é obra primacial para o estudo das relações entre os nossos dois países e ninguém mais indicado para fazê-lo que quem, como o autor, vem se dedicando à pesquisa de fatos e temas relacionados com a história e a literatura latino- americanas. Deu o autor ao seu trabalho o título: “The emperor of Brazil and his New England friends”. -

Universidade De Brasília Instituto De Artes Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Artes Visuais

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais Viajar, observar e registrar: coleção e circulação da produção visual de Maria Graham Maria de Fátima Medeiros de Souza Brasília, 2020 1 Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais Viajar, observar e registrar: coleção e circulação da produção visual de Maria Graham Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais do Instituto de Artes da Universidade de Brasília como pré-requisito para a obtenção do Título de Doutora em Artes Visuais. Linha de Pesquisa: Teoria e História da Arte Discente: Maria de Fátima Medeiros de Souza Orientador: Dr. Emerson Dionisio Gomes de Oliveira (UnB) Co orientadora: Dra. Elaine Cristina Dias (UNIFESP) Brasília, 2020 2 3 Aos meus pais, Maria Licinha e Pedro Madeiro. 4 Agradecimentos Primeiramente, agradeço aos orientadores, o professor Dr. Emerson Dionisio Gomes de Oliveira do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arte Visuais da Universidade de Brasília, e a professora Dra. Elaine Cristina Dias do Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte da Universidade Federal de São Paulo, que indicaram caminhos relevantes para o desenvolvimento desta pesquisa sobre Maria Graham; À professora Dra. Maria Margaret Lopes do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Universidade de Brasília e do Programa de Pós-Graduação da Universidade de Évora (Portugal), e à professora Dra. Vera Marisa Pugliese do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes Visuais da Universidade de Brasília, que fizeram parte da banca de qualificação desta tese de doutorado; À professora Dra. Maria Margaret Lopes do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Informação da Universidade de Brasília e do Programa de Pós-Graduação da Universidade de Évora (Portugal), à professora Dra. -

Malaspina's Visit to Doubtful Sound, New Zealand, 25 February 1793

New Zealand and the EU Revisiting the Malaspina Expedition: Cultural Contacts and Contexts November 2011 Guest Editor, José Colmeiro School of European Languages and Literatures The University of Auckland Anne Salmond Mercedes Camino Anthropology Department Hispanic Studies Department The University of Auckland Lancaster University Phyllis S. Herda James Braund Anthropology Department School of European Languages The University of Auckland and Literatures The University of Auckland Research Series Editor: Hannah Brodsky-Pevzner Honorary Research Fellow School of European Languages and Literatures The University of Auckland The Europe Institute is a multi-disciplinary research institute that brings together researchers from a large number of different departments, including Anthropology, Art History, International Business and Commerce, Economics, European Languages and Literature, Film, Media and TV Studies, Law, and Political Studies. The mission of the Institute is to promote research, scholarship and teaching on contemporary Europe and EU-related issues, including social and economic relations, political processes, trade and investment, security, human rights, education, culture and collaboration on shared Europe-New Zealand concerns. ISSN 1177 8229 © The Publishers and each contributor CONTENTS PREFACE: JOSÉ COLMEIRO European Explorations in the South Pacific: The Underexplored Narratives of the Malaspina Expedition v ANNE SALMOND Not a Trace, however Remote, of Inhabitants: Malaspina’s Visit to Doubtful Sound, New Zealand, 25 February -

Uma Análise Dos Auxiliares Na Expedição De Louis Agassiz Ao Brasil (1865-1866)

Casa de Oswaldo Cruz – FIOCRUZ Programa de Pós-Graduação em História das Ciências e da Saúde ANDERSON PEREIRA ANTUNES A REDE DOS INVISÍVEIS: UMA ANÁLISE DOS AUXILIARES NA EXPEDIÇÃO DE LOUIS AGASSIZ AO BRASIL (1865-1866) Rio de Janeiro 2015 ii ANDERSON PEREIRA ANTUNES A REDE DOS INVISÍVEIS: UMA ANÁLISE DOS AUXILIARES NA EXPEDIÇÃO DE LOUIS AGASSIZ AO BRASIL (1865-1866) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Curso de Pós-Graduação em História das Ciências e da Saúde da Casa de Oswaldo Cruz-Fiocruz, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Grau de Mestre. Área de Concentração: História das Ciências Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Luisa Medeiros Massarani Co-orientador: Prof. Dr. Ildeu de Castro Moreira Rio de Janeiro 2015 iii ANDERSON PEREIRA ANTUNES A REDE DOS INVISÍVEIS: UMA ANÁLISE DOS AUXILIARES NA EXPEDIÇÃO DE LOUIS AGASSIZ AO BRASIL (1865-1866) Dissertação de mestrado apresentada ao Curso de Pós-Graduação em História das Ciências e da Saúde da Casa de Oswaldo Cruz-Fiocruz, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Grau de Mestre. Área de Concentração: História das Ciências BANCA EXAMINADORA ___________________________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Luisa Medeiros Massarani (Núcleo de Estudos da Divulgação Científica, Museu da Vida, Casa de Oswaldo Cruz, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz) – Orientadora ___________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Ildeu de Castro Moreira (Instituto de Física, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro) – Co-orientador ___________________________________________________________________ -

Visconde Do Uruguai E Sua Atuação Diplomática Para a Consolidação Da Política Externa Do Império Ministério Das Relações Exteriores

O VISCONDE DO URUGUAI E SUA ATUAÇÃO DIPLOMÁTICA PARA A CONSOLIDAÇÃO DA POLÍTICA EXTERNA DO IMPÉRIO MINISTÉRIO DAS RELAÇÕES EXTERIORES Ministro de Estado Embaixador Antonio de Aguiar Patriota Secretário-Geral Embaixador Ruy Nunes Pinto Nogueira FUNDAÇÃO A LEXANDRE DE GUSMÃO Presidente Embaixador Gilberto Vergne Saboia Instituto de Pesquisa de Relações Internacionais Diretor Embaixador José Vicente de Sá Pimentel Centro de História e Documentação Diplomática Diretor Embaixador Maurício E. Cortes Costa A Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão, instituída em 1971, é uma fundação pública vinculada ao Ministério das Relações Exteriores e tem a finalidade de levar à sociedade civil informações sobre a realidade internacional e sobre aspectos da pauta diplomática brasileira. Sua missão é promover a sensibilização da opinião pública nacional para os temas de relações internacionais e para a política externa brasileira. Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo, Sala 1 70170-900 Brasília, DF Telefones: (61) 3411-6033/6034 Fax: (61) 3411-9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br MIGUEL GUSTAVO DE PAIVA TORRES O Visconde do Uruguai e sua atuação diplomática para a consolidação da política externa do Império Brasília, 2011 Direitos de publicação reservados à Fundação Alexandre de Gusmão Ministério das Relações Exteriores Esplanada dos Ministérios, Bloco H Anexo II, Térreo 70170-900 Brasília DF Telefones: (61) 3411-6033/6034 Fax: (61) 3411-9125 Site: www.funag.gov.br E-mail: [email protected] Equipe Técnica: Henrique da Silveira Sardinha Pinto Filho Fernanda Antunes Siqueira Fernanda Leal Wanderley Juliana Corrêa de Freitas Programação Visual e Diagramação: Juliana Orem Impresso no Brasil 2011 Torres, Miguel Gustavo de Paiva. -

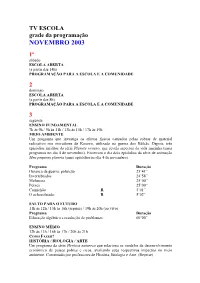

Novembro 2003

TV ESCOLA grade da programação NOVEMBRO 2003 1º sábado ESCOLA ABERTA (a partir das 14h) PROGRAMAÇÃO PARA A ESCOLA E A COMUNIDADE 2 domingo ESCOLA ABERTA (a partir das 8h) PROGRAMAÇÃO PARA A ESCOLA E A COMUNIDADE 3 segunda ENSINO FUNDAMENTAL 7h às 9h / 9h às 11h / 13h às 15h / 17h às 19h MEIO AMBIENTE Um programa que investiga os efeitos físicos causados pelas sobras de material radioativo nos moradores de Kosovo, utilizado na guerra dos Bálcãs. Depois, três episódios inéditos da série Planeta oceano, que revela aspectos da vida marinha (mais programas no dia 4 de novembro). Encerram o dia dois episódios da série de animação Meu pequeno planeta (mais episódios no dia 4 de novembro). Programa Duração Herança da guerra: poluição 25’41” Invertebrados 24’58” Moluscos 25’00” Peixes 25’00” Comichão R 5’01” O achocolatado R 5’02” SALTO PARA O FUTURO 11h às 12h / 15h às 16h (reprise) / 19h às 20h (ao vivo) Programa Duração Educação algébrica e resolução de problemas 60’00” ENSINO MÉDIO 12h às 13h / 16h às 17h / 20h às 21h COMO FAZER? HISTÓRIA / BIOLOGIA / ARTE Um programa da série Heróica natureza que relaciona os modelos de desenvolvimento econômico de países pobres e ricos, avaliando seus respectivos impactos no meio ambiente. Comentado por professores de História, Biologia e Arte. (Reprise) Programa Duração Pobres e sujos, ricos e poluidores 27’21” 4 terça ENSINO FUNDAMENTAL 7h às 9h / 9h às 11h / 13h às 15h / 17h às 19h MEIO AMBIENTE Mais quatro episódios inéditos da série Planeta oceano (outros episódios no dia 3 de novembro).