Sudan Studies Was Originally Distributed in Hard Copy to Members of the Sudan Studies Society of the United Kingdom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019

1 Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019 IN PREPARATION FOR THE GENERAL CHAPTER OF MAY 2020 THE HISTORY OF CAMILLIAN SUPERIOR GENERALS AND GENERAL CHAPTERS: Some Historical Notes and Curiosities! Fr. Leo Pessini The superior general presides over the government of the entire Order. He has jurisdiction and authority over the provinces, the vice-provinces, the delegations, the houses and the religious (Constitution, 97). The superior general also consults the provincial superiors, vice-provincials and delegates in matters of major importance which concern the entire Order. If possible once a year and, whenever this is necessary, he shall convene the provincials, vice-provincials and delegates…to address various questions with the general consulta (General Statutes, 79) The general chapter, wherein resides the supreme collegial authority of the Order, is formed of representatives of the whole Order and thus is a sign of unity in charity (Constitution, 113) Introduction We are beginning the preparations for the fifty-ninth General Chapter of the Order of Camillians which we will celebrate starting on 2 May 2020 and whose subject will be ‘Which Camillian Prophecy Today? Peering into the Past and Living in the Present Trying to Serve as Samaritans and Journeying with Hope towards the Future’ The subject of prophecy is once again of great contemporary relevance and appears always new as a challenge for consecrated life today. Let us welcome the invitation of Pope Francis who has repeatedly called our attention to this specific characteristic of consecrated life: prophecy! ‘I hope that you will wake up the world’ because the known characteristic of consecrated life is prophecy. -

Don Bosco's Missionary Dreams-Images of a Worldwide Salesian a Posto Late

DON BOSCO'S MISSIONARY DREAMS-IMAGES OF A WORLDWIDE SALESIAN A POSTO LATE Prefatory Notel Because of the vastness of the subject and of the amount of material involved, this essay will be presented in two installments. In this issue, after a general introduction, we will discuss the First Missionary Dream, expressing Don Bosco's original option for the missions; and then, the two "South American" missionary dreams, projecting the expansion of the Salesian work in that sub continent. In the next issue we will present the two world-oriented dreams, and we will conclude with an interpretation of the missionary dreams as a whole, as well as of particular facets thereof. Introduction he Biographical Memoirs and the Documenti that preceded them record over T150 narratives of dreams attributed to Don Bosco.2 Many of them are 1 The present study is a rewritten version of two earlier essays by the same author: "I Sogni in Don Bosco. Esame storico-critico, significato e ruolo profetico missionario per I'America Latina," in Don Bosco e Brasilia. Profezia, realta sociale e diritto, a cura di Cosimo Semeraro. Padova: CEDAM, 1990, p. 85-130; and "Don Bosco's Mission Dreams in Context," Indian Missiological Review 10 (1988) 9-52. In spite of basic identity with the earlier drafts, it was felt that in its present form the essay will interest the readers of the Journal. 2 The Italian Memorie Biografiche are cited as IBM The English Biographical Memoirs (volumes I-XV) are cited as EBM. [Giovanni Battista Lemoyne] Documenti per scrivere la storia di D. -

The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto Da Postioma

Social Sciences and Missions 32 (2019) 148–176 Social Sciences and Missions Sciences sociales et missions brill.com/ssm The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma Laura António Nhaueleque Open University, Lisbon [email protected] Luca Bussotti CEI-ISCTE—University Institute of Lisbon and, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show the evolution of the conceptualisation of Africa according to the Catholic Church, using as its key references Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma, two Italian missionaries who lived in the 19th century and 20th century respectively. Through them, the article attempts to interpret how the Catholic Church has conceived and implemented its relationships with the African continent in the last two centuries. The article uses history to analyse the thought of the two authors using a qualitative and comparative methodology. Résumé Le but de cet article est de montrer l’évolution de la conceptualisation de l’Afrique par l’église catholique, à partir des cas de Daniele Comboni et Adalberto da Postioma, deux missionnaires italiens du 19ème et 20ème siècles. À travers eux, l’article cherche à interpréter la manière dont l’église catholique a conçu et mis en œuvre ses relations avec le continent africain au cours des deux derniers siècles. L’article utilise l’histoire pour analyser la pensée des deux auteurs, en mobilisant une méthodologie qualitative et comparative. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/18748945-03201004Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 12:36:38PM via free access the conceptualisation of africa in the catholic church 149 Keywords Comboni – Postioma – Catholic Thought – Africa – mission Mots-clés Comboni – Postioma – pensée catholique – Afrique – mission This article aims to analyse how the Catholic Church dealt with the “African question”. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com08/31/2021 02:46:22AM

Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 07:30:01PM via free access AFRIKA FOCUS, Vol.3, Nr.3-4, I987, pp.237-285 CONGOLESE CHILDREN AT THE CONGO HOUSE IN COLWYN BAY (NORTH WALES, GREAT-BRITAIN), AT THE END OF THE 19th CENTURY. Unpublished documents. Zana Aziza ETAMBALA. Bursaal, K.U.Leuven Departement Moderne Geschiedenis Blijde Inkomststraat 21/5 B-3OOO Leuven CURRENT RESEARCH INTEREST : - the presence of Africans in Europe : 19-20 th century - the attitude of the Belgian Catholic Church towards Congo Free State SUMMARY In the present study we like to focus the attention on the presence of Congolese children at the Congo House in Colwyn Bay (North Wales, Great-Britain) during the last decade of the 19th century. The idea, which William Hughes conceived and which consisted of educating Congolese, in a first phase, and other African youth, in a second one, never received a just interest. The experiment of Hughes, a former baptist missionary, was a unique specimen for Great-Britain. Henry Morton Stanley and King Leopold II were a little bit involved in the successful start of this initiative. But this article has particularly in view an identification of the Congolese boys and girls who frequented the 'Congo House1! KEYWORDS : Colwyn Bay, Congolese children, Education, End of 19th century, W. Hughes Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 07:30:01PM via free access - 238 - INTRODUCTION During the last quarter of the 19th century, a lot of African children were sent out of the continent in order to receive a western education. Several young black boys and girls were taken to Belgium as well to Sweden, France, Germany, Italy, Malta, Great-Britain, Portugal, the United States and other countries (1). -

Don Bosco's Missionary Call and China

49-rss(215-294)studi.qxd 19-12-2006 14:38 Pagina 215 STUDI DON BOSCO’S MISSIONARY CALL AND CHINA Carlo Socol * Comparative Chronology: (A) General Events (B) Salesian Events 1839-1842 1st Opium War: 1841 Don Bosco ordained a priest Treaty of Nanking 1840/09 Martyrdom of Gabriel Perboyre 1845 1st edition of the Storia Ecclesiastica 1843 Cause of beatification of Perboyre begins 1853-1854 Japan opens to outside world 1859 Birth of the Salesian Society 1856 Martyrdom of Auguste Chapdelaine nd 1864 Comboni at Valdocco speaks 1858-1860 2 Opium War about Africa 1860/10 Treaty of Tientsin: French Protectorate 1869 The Holy See approves 1862 Canonization of Martyrs the Salesian Society of Nagasaki (1597) 1869 Mons. Lavigerie invites Salesians 1867 Beatification of Japanese Martyrs to Algeria (1617-32) 1869-70 3rd Edition of the 1867/09 Bishop E. Zanoli Storia Ecclesiastica of Hupei visits Valdocco 1870 Negotiations for San Francisco 1870/07 Comboni’s proposal for Cairo 1869-1870 1st Vatican Council 1871-72 1st missionary dream 1870 Bishops from China visit Valdocco 1873/10 Negotiations with 1870 Anti-foreign violence in Tientsin Msgr. T. Raimondi begin 1873/04 Consecration of Shrine of Zo-sé 1874/04 Salesian Constitutions approved st (Shanghai) 1875/11 1 Mission to Argentina 1874 Anti-foreign violence in Yunnan 1885/07 Dream about Angel of Arphaxad 1875 Anti-foreign violence in Szechwan 1886/04 Dream of Barcelona: 1885-1886 Persecution in Kiangsi Peking, Meaco… 1886/10 Conversation with A. Conelli in San Benigno 1886 Spiritual Testament 1888/1 Death of Don Bosco 1890 Conelli contacts Rondina about Macao * Salesiano, docente di Storia Ecclesiastica presso lo Holy Spirit Seminary di Hong Kong. -

1 Missionary Institutes in Europe: What

MISSIONARY INSTITUTES IN EUROPE: WHAT FUTURE? Introduction The title we have adopted may lead some readers to a hasty conclusion, even before reading the text: that we are concerned about the survival of missionary institutes due to the lack of missionary vocations in Europe. We say straight away that this is not our starting point, even if, as we shall see, the question of the general lack of missionary vocations in Europe cannot be avoided when we talk about missionary institutes in this continent. Our point of departure is another: the perception of an uprooting of missionary Institutes from the local Churches of Europe. On the one hand, it seems that the Churches of Europe no longer recognise missionary institutes as their actualised missionary expressions and, on the other hand, it seems that missionary institutes have moved away from the sensitivity and life of the European Churches. Obviously, we are only talking about missionary institutes in Europe and we are not referring to their situation in Africa (or America and Asia), for example, where their apostolic fruitfulness is evident and their insertion in the local Churches is easier and less problematic. This our starting point may not be shared and/or it may be rejected. But it is from this observation that we start. Faced with an evident lack of apostolic fruitfulness and creativity (which goes far beyond the question of vocations), we think that we cannot avoid the question of the rootedness, or lack thereof, of missionary institutes in the local Churches that have seen them born. We write in first person plural, because we want to capture the benevolence of the reader and involve him/her in the writing of the narrative, perhaps building their own, adopting the one proposed here or integrating it with different points of view. -

In Dialogue with the Comboni Missionary Sisters

DISCERNING A SPIRITUALITY FOR TRANSFORMATIVE MISSION: IN DIALOGUE WITH THE COMBONI MISSIONARY SISTERS by LAURA LEPORI submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR. MAGDALENE KARECKI CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. JNJ KRITZINGER JANUARY 2019 ii Summary This research seeks to acquire a deep understanding of how spirituality and mission correlate and shape each other. An initial review of missiological texts has revealed that spirituality is not often (nor explicitly) taken into consideration by missiologists. Likewise, mission generally does not occupy a central place within the academic discipline of spirituality. I contend that spirituality is the motor of mission and missiology and therefore cannot be only briefly mentioned or omitted from missiological discourse. This thesis explores this relationship with a specific focus on the Comboni Missionary Sisters. It explores the mission spirituality of their founder, Daniel Comboni, how this is taken up by the Comboni Missionary Sisters and how it shapes their lives and their being in mission. The research also aims to foster some transformations. It explores new ways for the Sisters to express their ways of being in mission in the context(s) in which they live, in order to be faithful to Comboni’s charism as well as to be a relevant presence today. The thesis proposes that mission spirituality be studied and lived by making use a Mission spirituality spiral. Its six dimensions are: spirituality, at the centre and all along the spiral; encounter with other(s) and with the context; context analysis; theological reflection (encounter with Scripture and Tradition); discernment for transformative ways of being in mission and reflexivity. -

Gender and Migration in Italy C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Gender and Migration in Italy A Multilayered Perspective© Copyrighted Material provided by Archivio della ricerca- Università di Roma La Sapienza University of Rome ‘La Sapienza’, Italy ELISA OLIVITOEdited by brought to you by www.ashg ate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.a shgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com www.ashgate.com CORE © Copyrighted Material © Elisa Olivito 2016 All rights reserved. system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Elisa Olivito has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents be identified as the editor of this work. Publishedby Ashgate Publishing Limited Ashgate Publishing Company Wey Court East Union Farnham Burlington,VT No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval Surrey,7PGU9T USA England Road 3-1Suite www.ashgate.com © Copyrighted Material British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Olivito, Elisa, author. Gender and migration in Italy : a multilayered perspective / by Elisa Olivito. pages cm -- (Law and migration) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4724-5575-8 (hardback) -- ISBN 978-1-4724-5576-5 (ebook) -- ISBN 978-1-4724-5577-2 (epub) 1. Foreign workers--Legal status, laws, etc.--Italy. 2. Women migrant labor--Italy. I. KKH1328.A44O45 2015 304.80945--dc23 110 Cherry Street ISBN 9781472455758 (hbk) ISBN 9781472455765 (ebk – PDF) T ISBN 9781472455772 (ebk – ePUB) itle. -

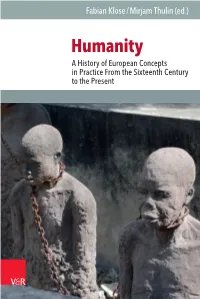

Humanity. a History of European Concepts in Practice From

Fabian Klose / Mirjam Thulin (ed.) Humanity A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Abendländische Religionsgeschichte Abteilung für Universalgeschichte Edited by Irene Dingel and Johannes Paulmann Supplement 110 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Humanity A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present Edited by Fabian Klose and Mirjam Thulin Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online: https://dnb.de. © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International license, at DOI 10.10139/9783666101458. For a copy of this license go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any use in cases other than those permitted by this license requires the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover picture: The Monument to the Slaves in the Grounds of Christ Church, Zanzibar. © Fabian Klose Typesetting: Vanessa Weber, Mainz Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1056 ISBN 978-3-666-10145-8 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Acknowledgments The present volume grew out of the interdisciplinary conference “Human- ity – a History of European Concepts in Practice”, sponsored by the research group “Concepts of Humanity and Humanitarian Practice”, in October 2015 at the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz. -

White Paper on Creativity Towards an Italian Model of Development

White paper on creativity Towards an Italian model of development Edited by Walter Santagata Cover image: Michelangelo Pistoletto “ConTatto” 1962 - 2007 Screen print on polished reflecting stainless steel, 22 x 16 x 23 cm Edition for the Ministry of Heritage and Cultural Activity Photograph: J.E.S. English Translation by David Kerr Editing by Federica Cau Italian original version: Walter Santagata (Editor) “Libro Bianco sulla Creatività. Per un modello italiano di sviluppo”. Università Bocconi Editore, Milano. 2009 Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution – NonCommercial – ShareAlike 2.5 license. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ or send a letter to “Creative Commons, 543 Howard Street, 5th Floor, San Francisco, California, 94105, USA.” Index Acknowledgements ....................................................................9 Foreword................................................................................... 10 Part I ......................................................................................... 12 1 Culture, Creativity and Industry: an Italian model .................. 14 Walter Santagata, Enrico Bertacchini, Paola Borrione 1.1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................14 1.2 Creativity and social quality: building an Italian model...................................................15 1.3 Styles and models of cultural production and creativity.................................................21 -

Daniele Comboni

Testimone di Pace Daniele Comboni Daniele Comboni, futuro fondatore dei Missionari Comboniani, nasce a Limone sul Garda il 15 marzo 1831 in una famiglia di contadini al servizio di un ricco signore della zona; compie gli studi presso l’istituto fondato da don Nicola Mazza a Verona. In questi anni Daniele scopre la sua vocazione al sacerdozio, viene ordinato sacerdote nel 1854, completa gli studi di filosofia e teologia e soprattutto si apre alla missione dell’Africa Centrale, attratto dalle testimonianze dei primi missionari mazziani reduci dal continente africano. Nel 1857 intraprende il suo primo viaggio in Africa insieme ad altri cinque missionari mazziani. Dopo quattro mesi di viaggio la spedizione arriva a Khartoum, capitale del Sudan. Daniele si rende subito conto delle difficoltà che la nuova missione comporta:fatiche, clima insopportabile, malattie, morte di numerosi compagni missionari, povertà, ma è proprio questa realtà che lo porta a perseverare nella sua volontà di impegnarsi nella missione “O Nigrizia, o morte”, o l’Africa o morte. Le necessità dell’Africa e della sua gente spingono Daniele a mettere a punto, tornato in Italia, una nuova strategia missionaria, il Piano per la rigenerazione dell’Africa, un progetto sintetizzabile nella frase “Salvare l’Africa con l’Africa”. Egli crede nella necessità che gli Africani diventino essi stessi protagonisti della loro salvezza: per far questo spera di far nascere in Africa degli istituti, retti da ordini religiosi, per accogliere i giovani africani, educarli alla fede e renderli protagonisti della loro stessa evangelizzazione. L’idea centrale di questo “Piano” è quella di coinvolgere i 12 vicariati, le 9 prefetture e le 12 diocesi che circondavano l’Africa in un’azione concentrica e progressiva verso le regioni interne, attuando il metodo della “rigenerazione dell’Africa con l’Africa”. -

Our Inheritance

FR FRANCESCO PIERLI MCCJ OUR INHERITANCE COMBONI MISSIONARIES OF THE HEART OF JESUS ABBREVIATIONS ACR Archivio Comboniano Roma. AG Ad Gentes, Vatican II, 1965. CA Centesimus Annus, John-Paul II, Ency. Let., 1991. CA Chapter Acts. ChL Christifideles Laici, John-Paul II, Apost. Exort., 1988. DM Dives in Misericordia, John-Paul, Ency. Let., 1980. EN Evangelii Nuntiandi, Paul VI, Apost. Exort., 1975. EP Evangelii Praecones, Pious XII, Ency. Let., 1951. FD Fidei Donum, Pious XII, Ency. Let., 1957. GS Gaudium et Spes, Vatican II, 1965. LG Lumen Gentium, Vatican II, 1964. MC Marialis Cultus, Paul VI, Apost. Exort., 1974. MI Maximum Illud, Ency. Let., Benedict XV, 1919. MuR Mutuae Relationes, Congregation for religious, 1978. NA Nostra Aetate, Vatican II, 1965. PC Perfectae Caritatis, Vatican II, 1965. PO Presbyterorum Ordinis, Vatican II, 1965. Positio Positio super virtutibus Servi Dei Danielis Comboni, Roma 1988. Prp Princeps Pastorum, John XXIII, Ency. Let., 1959. Ratio Ratio fundamentalis institutionis et studiorum, Comboni Missionaries, Rome, 1991. RC Redemptoris Custos, John-Paul II, Apost. Exort., 1989. RD Redemptoris Donum, John-Paul II, Apost. Exort., 1984. RE Rerum Ecclesiae, Pious XII, Ency. Let., 1926. RL Rule of Life, Comboni Missionaries, Rome, 1988. RM Redemptoris Missio, John-Paul II, Ency. Let., 1990. S Scritti, the writings of Daniel Comboni in Italian, EMI Press, Bologna, 1991. SD Salvifici Doloris, John-Paul II, Apost. Let., 1984. PREFACE Being heirs to the Apostle of Africa was made the dominant note for the immediate future when the 14th. General Chapter chose the motto "With Daniel Comboni Today." So I am happy to present these outlines of Comboni missionary spirituality written by Fr.