Downloaded from Brill.Com08/31/2021 02:46:22AM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019

1 Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019 IN PREPARATION FOR THE GENERAL CHAPTER OF MAY 2020 THE HISTORY OF CAMILLIAN SUPERIOR GENERALS AND GENERAL CHAPTERS: Some Historical Notes and Curiosities! Fr. Leo Pessini The superior general presides over the government of the entire Order. He has jurisdiction and authority over the provinces, the vice-provinces, the delegations, the houses and the religious (Constitution, 97). The superior general also consults the provincial superiors, vice-provincials and delegates in matters of major importance which concern the entire Order. If possible once a year and, whenever this is necessary, he shall convene the provincials, vice-provincials and delegates…to address various questions with the general consulta (General Statutes, 79) The general chapter, wherein resides the supreme collegial authority of the Order, is formed of representatives of the whole Order and thus is a sign of unity in charity (Constitution, 113) Introduction We are beginning the preparations for the fifty-ninth General Chapter of the Order of Camillians which we will celebrate starting on 2 May 2020 and whose subject will be ‘Which Camillian Prophecy Today? Peering into the Past and Living in the Present Trying to Serve as Samaritans and Journeying with Hope towards the Future’ The subject of prophecy is once again of great contemporary relevance and appears always new as a challenge for consecrated life today. Let us welcome the invitation of Pope Francis who has repeatedly called our attention to this specific characteristic of consecrated life: prophecy! ‘I hope that you will wake up the world’ because the known characteristic of consecrated life is prophecy. -

Don Bosco's Missionary Dreams-Images of a Worldwide Salesian a Posto Late

DON BOSCO'S MISSIONARY DREAMS-IMAGES OF A WORLDWIDE SALESIAN A POSTO LATE Prefatory Notel Because of the vastness of the subject and of the amount of material involved, this essay will be presented in two installments. In this issue, after a general introduction, we will discuss the First Missionary Dream, expressing Don Bosco's original option for the missions; and then, the two "South American" missionary dreams, projecting the expansion of the Salesian work in that sub continent. In the next issue we will present the two world-oriented dreams, and we will conclude with an interpretation of the missionary dreams as a whole, as well as of particular facets thereof. Introduction he Biographical Memoirs and the Documenti that preceded them record over T150 narratives of dreams attributed to Don Bosco.2 Many of them are 1 The present study is a rewritten version of two earlier essays by the same author: "I Sogni in Don Bosco. Esame storico-critico, significato e ruolo profetico missionario per I'America Latina," in Don Bosco e Brasilia. Profezia, realta sociale e diritto, a cura di Cosimo Semeraro. Padova: CEDAM, 1990, p. 85-130; and "Don Bosco's Mission Dreams in Context," Indian Missiological Review 10 (1988) 9-52. In spite of basic identity with the earlier drafts, it was felt that in its present form the essay will interest the readers of the Journal. 2 The Italian Memorie Biografiche are cited as IBM The English Biographical Memoirs (volumes I-XV) are cited as EBM. [Giovanni Battista Lemoyne] Documenti per scrivere la storia di D. -

74950 4 Rhos Gwyn, 493 Abergele Road, Old Colwyn

4 MOSTYN STREET 47 PENRHYN AVENUE LLANDUDNO RHOS ON SEA, COLWYN BAY AUCTIONEERS LL30 2PS LL28 4PS (01492) 875125 (01492) 544551 ESTATE AGENTS email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Please contact Rhos on Sea Office £74,950 4 Rhos Gwyn, 493 Abergele Road, Old Colwyn, Colwyn Bay, LL29 9AE A Purpose Built Two Bedroom Apartment located at the rear of the development with far reaching views of the sea and coastline and within half a mile of Old Colwyn village shops, promenade and bus services. The apartment is accessed by a communal entrance door from the front and down a staircase to the lower level. The apartment comprises: entrance door to the hallway; lounge-dining room with double glazed door to the balcony; modern kitchen; principal bedroom with fitted wardrobes; bedroom two and fully tiled shower room. It benefits from electric heating and upvc double glazing. Outside the communal gardens are maintained by the Management Company. There is a garage in a block and communal residents parking. www.bdahomesales.co.uk 4 Rhos Gwyn, 493 Abergele Road, Old Colwyn, Colwyn Bay, LL29 9AE The accommodation comprises: Upvc double glazed door to the: Communal entrance into the hallway and ENCLOSED BALCONY steps down to lower level. Apartment With sea views. door for no. 4. HALLWAY Airing cupboard, electric wall heater, entry phone. LOUNGE/DINING ROOM 7.27m x 3.15m (23'10" x 10'4") Maximum narrowing to 2.40m (7'10") Decorative coving and ceiling roses, two electric wall heaters, one storage heater. Sliding door to the: KITCHEN 2.79m x 1.73m (9'2" x 5'8") Fully tiled walls, clad ceiling with inset downlighters, modern wall, base and drawer units with open display and one illuminated glazed cabinet, round edge worktops incorporating single drainer sink with mixer tap, four ring halogen hob inset to worktop with extractor hood, plumbing for an automatic washing machine and space for fridge/freezer, ceramic tile floor. -

Gwynedd Archives, Caernarvon Record Office

GB 0219 Porter Gwynedd Archives, Caernarvon Record Office This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 29348 The National Archives PORTER & C 0. PAPERS Caernarvonshire Record Office 1961 AN XHXBB2M 1*131! of records deposited by Messrs. Porter and Co., Solicitors, Plas Vardre, Conraay, in the Caerma^onshire Iteeord Office in February 1901. ggeaegg of th'.*. Roart of Petty, fusions 1^0 Registers of the Court, 1337-96, 1005-1905. (There are 2 Registers covering the years 2/537-90; one was vised when the court cat at Corrvny, the other when it sat at Llazviudna.) 7. Rough Minute Book, 139-4-97* 8-9 J&gistrateo1 Clerk'3 Fee Books, 1379-3-4, 1909-14. 10. Security Book, 1397-1913. 11. Fsynsnts Book, 1334-90. 12. Social Sessions Boole, 1339-1955. 13. fctty Sessional Parser o, 3893-1919 (1 snail bundle) ^* BEBffc filiation Agreements and RcleeseCj, 1333-1924. (1 bundle) 13. Kteacranavira for the parish of Uynfnen to be policed by DenJjinhahire polios, 1390. (Hie pariah of Llynfaen VT&S, until 1922, a part of Caernar vorinhire.) Copy Shrievalty; ^ecprtU 10. letter Book covering the yearn 1391-92 an! 1923-24. Conray and Colwvn TVry Joint Water Supply Boajfl Recorcln 17. Reglctor of Mortgages, 1392-1909. 13. letter Book, 1892-3903. Receivers1 Records 25, Gro.rn Rentals: Ilarrlrcd of Isaf, 1902, 1901-05, 1908, 1910-11. 20. Artic3.es of clerkship, 1353-1325. Drafts (1 bundles 7 Items) 81* Abstracts of title, 1355-99, 1907-25. (5 bunllest a. -

Tyn Y Ffordd Cottage Later Known As Gwynfron Minffordd Road Llanddulas Conwy LL22 8EW

Gwynt y Mor Outreach Project Tyn y ffordd Cottage later known as Gwynfron Minffordd Road Llanddulas Conwy LL22 8EW researched and written by Gill. Jones ©Discovering Old Welsh Houses PLEASE NOTE ALL THE HOUSES IN THIS PROJECT ARE PRIVATE AND THERE IS NO ADMISSION TO ANY OF THE PROPERTIES Contents page 1. Early Background History 2 2. The Wynne Family of Garthewin and Bron y wendon 2 3. The Building of Tyn y Fford Cottage 3 4. 19 th Century 4 5. 20 th Century 19 6. 21 st Century 23 Appendix 1 The Wynnes of Garthewin & Bron y wendon 24 Acknowledgements With thanks for the support received from the Gwynt y Mor Community Investment Fund. 1 Early Background History Llanddulas is one of the ancient parishes of Denbighshire . Until 1878, the parish consisted of the two townships of Tre'r Llan and Tre'r Cefn , containing 606 acres. The name translates as the ‘church on the River Dulas’; it has been claimed that the proper ecclesiastical name is Llangynbryd , from Cynbryd the dedicatee of the church. The first written record, which almost inevitably relates to the church, is in the 1254 Norwich Taxation (The pope ordered a new assessment of clergy property for taxation purposes) and exhibits a form not so very different from today, Llanndulas . Later in the century there are some curious variations as with Thlantheles in 1287 and Landuglas in 1291 (The Lincoln taxation of Pope Nicholas) . It is conceivable that the original name was Nant Dulas derived from the nearby stream, particularly as Nandulas was referred to in 1284. -

View a List of Current Roadworks Within Conwy

BWLETIN GWAITH FFORDD / ROAD WORKS BULLETIN (C) = Cyswllt/Contact Gwaith Ffordd Rheolaeth Traffig Dros Dro Ffordd ar Gau Digwyddiad (AOO/OOH) = Road Works Temporary Traffic Control Road Closure Event Allan o Oriau/Out Of Hours Lleoliad Math o waith Dyddiadau Amser Lled lôn Sylwadau Location Type of work Dates Time Lane width Remarks JNCT BROOKLANDS TO PROPERTY NO 24 Ailwynebu Ffordd / Carriageway 19/10/2020 OPEN SPACES EAST Resurfacing 19/04/2022 (C) 01492 577613 DOLWEN ROAD (AOO/OOH) B5383 HEN GOLWYN / OLD COLWYN COMMENCED O/S COLWYN BAY FOOTBALL CLUB Ailwynebu Ffordd / Carriageway 19/10/2020 OPEN SPACES EAST Resurfacing 19/04/2022 (C) 01492 577613 LLANELIAN ROAD (AOO/OOH) B5383 HEN GOLWYN / OLD COLWYN COMMENCED from jct Pentre Ave to NW express way Gwaith Cynnal / Maintenance Work 26/07/2021 KYLE SALT 17/12/2021 (C) 01492 575924 DUNDONALD AVENUE (AOO/OOH) A548 ABERGELE COMMENCED Cemetary gates to laybys Gwaith Cynnal / Maintenance Work 06/09/2021 MWT CIVIL ENGINEERING 15/10/2021 (C) 01492 518960 ABER ROAD (AOO/OOH) 07484536219 (EKULT) C46600 LLANFAIRFECHAN COMMENCED 683* A543 Pentrefoelas to Groes Cynhaliaeth Cylchol / Cyclic 06/09/2021 OPEN SPACES SOUTH Maintenance 29/10/2021 (C) 01492 575337 PENTREFOELAS TO PONT TYDDYN (AOO/OOH) 01248 680033 A543 PENTREFOELAS COMMENCED A543 Pentrefoelas to Groes Cynhaliaeth Cylchol / Cyclic 06/09/2021 OPEN SPACES SOUTH Maintenance 29/10/2021 (C) 01492 575337 BRYNTRILLYN TO COTTAGE BRIDGE (AOO/OOH) 01248 680033 A543 BYLCHAU COMMENCED A543 Pentrefoelas to Groes Cynhaliaeth Cylchol / Cyclic 06/09/2021 -

The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto Da Postioma

Social Sciences and Missions 32 (2019) 148–176 Social Sciences and Missions Sciences sociales et missions brill.com/ssm The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma Laura António Nhaueleque Open University, Lisbon [email protected] Luca Bussotti CEI-ISCTE—University Institute of Lisbon and, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show the evolution of the conceptualisation of Africa according to the Catholic Church, using as its key references Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma, two Italian missionaries who lived in the 19th century and 20th century respectively. Through them, the article attempts to interpret how the Catholic Church has conceived and implemented its relationships with the African continent in the last two centuries. The article uses history to analyse the thought of the two authors using a qualitative and comparative methodology. Résumé Le but de cet article est de montrer l’évolution de la conceptualisation de l’Afrique par l’église catholique, à partir des cas de Daniele Comboni et Adalberto da Postioma, deux missionnaires italiens du 19ème et 20ème siècles. À travers eux, l’article cherche à interpréter la manière dont l’église catholique a conçu et mis en œuvre ses relations avec le continent africain au cours des deux derniers siècles. L’article utilise l’histoire pour analyser la pensée des deux auteurs, en mobilisant une méthodologie qualitative et comparative. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/18748945-03201004Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 12:36:38PM via free access the conceptualisation of africa in the catholic church 149 Keywords Comboni – Postioma – Catholic Thought – Africa – mission Mots-clés Comboni – Postioma – pensée catholique – Afrique – mission This article aims to analyse how the Catholic Church dealt with the “African question”. -

Applications and Decisions for Wales

OFFICE OF THE TRAFFIC COMMISSIONER (WALES) (CYMRU) APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS PUBLICATION NUMBER: 8619 PUBLICATION DATE: 20/11/2019 OBJECTION DEADLINE DATE: 11/12/2019 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Fax: 0113 248 8521 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The public counter at the above office is open from 9.30am to 4pm Monday to Friday The next edition of Applications and Decisions will be published on: 27/11/2019 Publication Price 60 pence (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] The Welsh Traffic Area Office welcomes correspondence in Welsh or English. Ardal Drafnidiaeth Cymru yn croesawu gohebiaeth yn Gymraeg neu yn Saesneg. APPLICATIONS AND DECISIONS Important Information All correspondence relating to public inquiries should be sent to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Wales) (Cymru) 38 George Road Edgbaston Birmingham B15 1PL The public counter in Birmingham is open for the receipt of documents between 9.30am and 4pm Monday Friday. There is no facility to make payments of any sort at the counter. General Notes Layout and presentation – Entries in each section (other than in section 5) are listed in alphabetical order. Each entry is prefaced by a reference number, which should be quoted in all correspondence or enquiries. Further notes precede each section, where appropriate. -

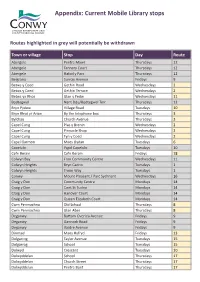

Mobile and Home Library Consultation Appendix

Appendix: Current Mobile Library stops Routes highlighted in grey will potentially be withdrawn Town or village Stop Day Route Abergele Pentre Mawr Thursdays 12 Abergele Tannery Court Thursdays 12 Abergele Hafod y Parc Thursdays 12 Belgrano Sunray Avenue Fridays 9 Betws y Coed Gethin Road Wednesdays 2 Betws y Coed Gethin Terrace Wednesdays 2 Betws yn Rhos Glan y Fedw Wednesdays 11 Bodtegwel Nant Ddu/Bodtegwel Terr. Thursdays 12 Bryn Pydew Village Road Tuesdays 10 Bryn Rhyd yr Arian By the telephone box Thursdays 3 Bylchau Church Avenue Thursdays 3 Capel Curig Plas y Brenin Wednesdays 2 Capel Curig Pinnacle Shop Wednesdays 2 Capel Curig Tyn y Coed Wednesdays 2 Capel Garmon Maes Llydan Tuesdays 6 Capelulo Ysgol Capelulo Tuesdays 10 Cefn Berain Cefn Berain Fridays 18 Colwyn Bay Fron Community Centre Wednesdays 11 Colwyn Heights Bryn Cadno Tuesdays 1 Colwyn Heights Troon Way Tuesdays 1 Conwy Mount Pleasant / Parc Sychnant Wednesdays 16 Craig y Don Community Centre Mondays 14 Craig y Don Cwrt St Tudno Mondays 14 Craig y Don Hanover Court Mondays 14 Craig y Don Queen Elizabeth Court Mondays 14 Cwm Penmachno Old School Thursdays 8 Cwm Penmachno Glan Aber Thursdays 8 Deganwy Bottom Overlea Avenue Fridays 9 Deganwy Gannock Road Fridays 9 Deganwy Vardre Avenue Fridays 9 Dinmael Maes Hyfryd Fridays 13 Dolgarrog Tayler Avenue Tuesdays 15 Dolgarrog School Tuesdays 15 Dolwyd Crescent Tuesdays 10 Dolwyddelan School Thursdays 17 Dolwyddelan Church Street Thursdays 17 Dolwyddelan Pentre Bont Thursdays 17 Dwygyfylchi Gwynan Park Tuesdays 10 Dwygyfylchi -

Ours Faithfully Yr Eiddoch Yn Gywir

CYNGOR TREF BAE COLWYN BAY OF COLWYN TOWN COUNCIL Mrs Tina Earley, PSLCC, Clerk & Finance Officer/Clerc a Swyddog Cyllid Cyngor Tref/Town Hall, Ffordd Rhiw Road, Bae Colwyn Bay, L L29 7TE Ffôn/Telephone: 01492 532248 Ebost/Email: [email protected] www.colwyn-tc.gov.uk Ein Cyf: TE/RD 0ur Ref: TE/RD 12 fed Ionawr 2021 12th January 2021 Annwyl Syr/Fadam Dear Sir/Madam Gŵys: Summons: Fech gwysir i fod yn bresennol mewn Cyfarfod You are summoned to attend a meeting of the o Gyngor Tref Bae Colwyn a gynhelir o hirbell Bay of Colwyn Town Council , to be held (trwy Zoom), am 6.30 p.m. nos Lun, 18 fed remotely (via Zoom) at 6.30 pm on Monday Ionawr 2021 .. 18 th January 2021. I ymuno yn y cyfarfod dilynwch y To join the meeting please follow the cyfarwyddiadau a anfonwyd yn yr e-bost sydd instructions sent in the accompanying e-mail. gyda hwn os gwelwch yn dda. Cysylltwch âr Please call the Clerk on 01492 532248 if you Clerc ar 01492 532248 os ydych angen ir require the log-in details for the meeting to be manylion mewngofnodi ar gyfer y cyfarfod cael sent to you. eu hanfon atoch. Yours faithfully Yr eiddoch yn gywir, Clerk to the Council Clerc y Cyngor AGENDA Cymraeg 1. Ymddiheuriadau am Absenoldeb: (a) Cynnal ennyd o dawelwch er cof am y Cynghorydd Gaye Howcroft-Jones (b) Cael unrhyw ymddiheuriadau am absenoldeb. 2. Cyhoeddiadau: Cael unrhyw gyhoeddiadau gan y Maer. 3. Datgan Cysylltiadau: Fe atgoffir pob aelod or angen iddynt ddatgan unrhyw gysylltiadau personol a / neu gysylltiadau syn rhagfarnu, a natur y fath gysylltiadau. -

14 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

14 bus time schedule & line map 14 Conwy - Llysfaen View In Website Mode The 14 bus line (Conwy - Llysfaen) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Conwy: 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM (2) Llandudno: 6:30 PM (3) Llysfaen: 3:45 PM (4) Mynydd Marian: 6:30 AM - 5:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 14 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 14 bus arriving. Direction: Conwy 14 bus Time Schedule 77 stops Conwy Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM Old Terminus, Llysfaen Tuesday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM Glyndwr Road Middle, Mynydd Marian Wednesday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM Gamar Road, Mynydd Marian Thursday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM Ffordd y Gamar, Llysfaen Community Friday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM St Cynfran`S Church, Mynydd Marian Pentregwyddel Road, Llysfaen Community Saturday 7:30 AM - 4:57 PM Semaphore Lodge, Mynydd Marian Bryn Awel, Mynydd Marian 14 bus Info Tan-Y-Graig Road, Mynydd Marian Direction: Conwy Stops: 77 Glas Coed, Penmaen-Rhos Trip Duration: 69 min Berth y Glyd Road, Llysfaen Community Line Summary: Old Terminus, Llysfaen, Glyndwr Road Middle, Mynydd Marian, Gamar Road, Mynydd Maenen, Penmaen-Rhos Marian, St Cynfran`S Church, Mynydd Marian, Maenen, Llysfaen Community Semaphore Lodge, Mynydd Marian, Bryn Awel, Mynydd Marian, Tan-Y-Graig Road, Mynydd Marian, Llysfaen Road Turn, Llysfaen Glas Coed, Penmaen-Rhos, Maenen, Penmaen-Rhos, Llysfaen Road Turn, Llysfaen, Highlands Road North, Highlands Road North, Penmaen-Rhos Penmaen-Rhos, Highlands Road, Penmaen-Rhos, Parc Cambria, -

Capability, Suitability & Climate Programme, ALC Soil Data

2018-19 Soil Policy Evidence Programme Capability, Suitability & Climate Programme, ALC Soil Data Digitisation 5th March 2020 Report Code: CSCP01 Mae’r ddogfen yma hefyd ar gael yn y Gymraeg. This document is also available in Welsh. © Crown copyright 2020 WG41030 Capability, Suitability & Climate Programme ALC Soil Data Digitisation Prepared by: Caroline Keay Date: 05 March 2020 Capability, Suitability & Climate Programme ALC Soil Data Digitisation Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Methods .......................................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Data Scanning ............................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Map Digitisation ......................................................................................................................... 1 2.3 Profile Data Digitisation ............................................................................................................. 2 2.4 Data Validation .......................................................................................................................... 4 APPENDIX A Context and Guidance (Written by Ian Rugg) ................................................................. 8 APPENDIX B Notes from Correspondence with Ian Rugg .................................................................