Gender and Migration in Italy C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019

1 Meeting of the Major Superiors of the Order of Camillians Rome, 14-18 March 2019 IN PREPARATION FOR THE GENERAL CHAPTER OF MAY 2020 THE HISTORY OF CAMILLIAN SUPERIOR GENERALS AND GENERAL CHAPTERS: Some Historical Notes and Curiosities! Fr. Leo Pessini The superior general presides over the government of the entire Order. He has jurisdiction and authority over the provinces, the vice-provinces, the delegations, the houses and the religious (Constitution, 97). The superior general also consults the provincial superiors, vice-provincials and delegates in matters of major importance which concern the entire Order. If possible once a year and, whenever this is necessary, he shall convene the provincials, vice-provincials and delegates…to address various questions with the general consulta (General Statutes, 79) The general chapter, wherein resides the supreme collegial authority of the Order, is formed of representatives of the whole Order and thus is a sign of unity in charity (Constitution, 113) Introduction We are beginning the preparations for the fifty-ninth General Chapter of the Order of Camillians which we will celebrate starting on 2 May 2020 and whose subject will be ‘Which Camillian Prophecy Today? Peering into the Past and Living in the Present Trying to Serve as Samaritans and Journeying with Hope towards the Future’ The subject of prophecy is once again of great contemporary relevance and appears always new as a challenge for consecrated life today. Let us welcome the invitation of Pope Francis who has repeatedly called our attention to this specific characteristic of consecrated life: prophecy! ‘I hope that you will wake up the world’ because the known characteristic of consecrated life is prophecy. -

Don Bosco's Missionary Dreams-Images of a Worldwide Salesian a Posto Late

DON BOSCO'S MISSIONARY DREAMS-IMAGES OF A WORLDWIDE SALESIAN A POSTO LATE Prefatory Notel Because of the vastness of the subject and of the amount of material involved, this essay will be presented in two installments. In this issue, after a general introduction, we will discuss the First Missionary Dream, expressing Don Bosco's original option for the missions; and then, the two "South American" missionary dreams, projecting the expansion of the Salesian work in that sub continent. In the next issue we will present the two world-oriented dreams, and we will conclude with an interpretation of the missionary dreams as a whole, as well as of particular facets thereof. Introduction he Biographical Memoirs and the Documenti that preceded them record over T150 narratives of dreams attributed to Don Bosco.2 Many of them are 1 The present study is a rewritten version of two earlier essays by the same author: "I Sogni in Don Bosco. Esame storico-critico, significato e ruolo profetico missionario per I'America Latina," in Don Bosco e Brasilia. Profezia, realta sociale e diritto, a cura di Cosimo Semeraro. Padova: CEDAM, 1990, p. 85-130; and "Don Bosco's Mission Dreams in Context," Indian Missiological Review 10 (1988) 9-52. In spite of basic identity with the earlier drafts, it was felt that in its present form the essay will interest the readers of the Journal. 2 The Italian Memorie Biografiche are cited as IBM The English Biographical Memoirs (volumes I-XV) are cited as EBM. [Giovanni Battista Lemoyne] Documenti per scrivere la storia di D. -

A Selection from the ASCETICAL LETTERS of ANTONIO ROSMINI

A selection from THE ASCETICAL LETTERS OF ANTONIO ROSMINI Volume II 1832-1836 Translated and edited by John Morris Inst. Ch. 1995 John Morris, Our Lady’s Convent, Park Road, Loughborough LE11 2EF ISBN 0 9518938 3 1 Phototypeset by The Midlands Book Typesetting Company, Loughborough Printed by Quorn Litho, Loughborough, Leics and reset with OCR 2004 ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... iii TRANSLATOR’S FOREWORD .................................................................................. 1 1. To His Holiness Pope Gregory XVI .......................................................................... 2 2. To Don Sebastian De Apollonia at Udine ................................................................. 4 3. To the deacon Don Clemente Alvazzi at Domodossola ........................................... 6 4. To Don G. B. Loewenbruck at Domodossola ........................................................... 7 5. To Don Pietro Bruti (curate at Praso) ...................................................................... 8 6. To Don Giacomo Molinari at Domodossola ............................................................. 9 7. To the priests Lissandrini and Teruggi at Arona .................................................. 10 8. To Niccolò Tommaseo in Florence .......................................................................... 12 9. To Don G. B. Loewenbruck at Domodossola ........................................................ -

The Stigmatine North Am Eric an Province

THE STIGMATINE NORTH AMERICAN PROVINCE Dedicated to the HOLY SPOUSES, MARY and JOSEPH General Appendix: Personalities † Rev. Joseph Henchey, CSS Tereza Lopes [Lay Stigmatine] On the Feast of the Holy Espousals, 2014 USA PROVINCE CHRONICLE - VOLUME I GENERAL APPENDIX: PERSONALITIES 2 GENERAL APPENDIX: PERSONALITIES A Short Biography The First Superior Generals: Father Giovanni Maria Marani, CSS – 1790 - † 1871 [1st Superior General: 1855 – 1871] Father Giovanni Battista Lenotti, CSS – 1817 - † 1875 [2nd Superior General: 1871 – 1875] Father Pietro Vignola, CSS – 1812 - † 1891 [3rd Superior General: 1875 – 1891] Father Pio Gurisatti, CSS – 1848 - † 1921 [4th Superior General: 1891 – 1911] Father Giovanni Battista Tommasi, CSS – 1866 - † 1954 [5th Superior General: 1911 – 1922] Father Giovanni Battista Zaupa, CSS – 1883 - † 1958 [6th Superior General: 1922 – 1934] Father Bruno Chiesa, CSS – 1887 - † 1952 [7th Superior General: 1934 – 1940] Father Giovanni Battista Zaupa, CSS – 1883 - † 1958 [8th Superior General: 1940 – 1946] Other Stigmatines: Father Carlo Zara, CSS – 1843 - † 1883 Father Andrea Sterza – 1847 - † 1898 Father Riccardo Tabarelli, CSS – 1850 - † 1909 Father Nicola Luigi Tomasi, CSS – 1857 - † 1928 Brother Domenico Valzachi, CSS – 1868 - † 1945 Father Alfredo Balestrazzi, CSS – 1871 - † 1845 Father Giovanni Castellani, CSS – 1871 - † 1936 Brother Giuseppe Zuliani, CSS – 1872 - † 1936 USA PROVINCE CHRONICLE - VOLUME I GENERAL APPENDIX: PERSONALITIES 3 Father Giuseppe Nardon, CSS – 1873 - † 1933 Father Emilio Baretella, CSS – -

The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto Da Postioma

Social Sciences and Missions 32 (2019) 148–176 Social Sciences and Missions Sciences sociales et missions brill.com/ssm The Conceptualisation of Africa in the Catholic Church Comparing Historically the Thought of Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma Laura António Nhaueleque Open University, Lisbon [email protected] Luca Bussotti CEI-ISCTE—University Institute of Lisbon and, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife [email protected] Abstract This article aims to show the evolution of the conceptualisation of Africa according to the Catholic Church, using as its key references Daniele Comboni and Adalberto da Postioma, two Italian missionaries who lived in the 19th century and 20th century respectively. Through them, the article attempts to interpret how the Catholic Church has conceived and implemented its relationships with the African continent in the last two centuries. The article uses history to analyse the thought of the two authors using a qualitative and comparative methodology. Résumé Le but de cet article est de montrer l’évolution de la conceptualisation de l’Afrique par l’église catholique, à partir des cas de Daniele Comboni et Adalberto da Postioma, deux missionnaires italiens du 19ème et 20ème siècles. À travers eux, l’article cherche à interpréter la manière dont l’église catholique a conçu et mis en œuvre ses relations avec le continent africain au cours des deux derniers siècles. L’article utilise l’histoire pour analyser la pensée des deux auteurs, en mobilisant une méthodologie qualitative et comparative. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2019 | doi:10.1163/18748945-03201004Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 12:36:38PM via free access the conceptualisation of africa in the catholic church 149 Keywords Comboni – Postioma – Catholic Thought – Africa – mission Mots-clés Comboni – Postioma – pensée catholique – Afrique – mission This article aims to analyse how the Catholic Church dealt with the “African question”. -

Spicilegium Historicum

SPICILEGIUM HISTORICUM Congregationis SSmi Redemptoris Annus LXI 2013 Fasc. 2 Collegium S. Alfonsi de Urbe LA RIVISTA SPICILEGIUM HISTORICUM Congregationis SSmi Redemptoris è una pubblicazione dell’Istituto Storico della Congregazione del Santissimo Redentore DIRETTORE Adam Owczarski SEGRETARIO DI REDAZIONE Emilio Lage CONSIGLIO DI REDAZIONE Alfonso V. Amarante, Álvaro Córdoba Chaves, Gilbert Enderle, Emilio Lage, Adam Owczarski DIRETTORE RESPONSABILE Alfonso V. Amarante SEDE Via Merulana, 31, C.P. 2458 I-00185 ROMA Tel [39] 06 494901, Fax [39] 06 49490243 e-mail: [email protected] ; [email protected] Con approvazione ecclesiastica Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Roma N. 310 del 14 giugno 1985 Ogni collaboratore si assume la responsabilità di ciò che scrive. SPICILEGIUM HISTORICUM CONGREGATIONIS SS MI REDEMPTORIS Annus LXI 2013 Fasc. 2 S T U D I A SHCSR 61 (2013) 257-338 PATRICE NYANDA , C.SS.R. LES RÉDEMPTORISTES AU BURKINA-NIGER ENTRE 1946 ET 1996 INTRODUCTION ; I. – PROJET DE FONDATION DES RÉDEMPTORISTES DANS LA COLONIE DU NIGER ; 1. – Remarques Préliminaires ; 2. – La Société des Missions Africaines de Lyon ; 3. – La figure incontournable du Père Constant Quillard ; 4. – L’intuition du P. Quillard ; 5. – Le «Missi» Rédemptoriste ; II. – TRACTATIONS DIVERSES DANS L ’ÉLABO - RATION DU PROJET ; 1. – Du côté des Rédemptoristes ; 2. – Du côté des Missions Afri- caines de Lyon ; 3. – Vers l’approbation du projet ; 4. – Établissement des premiers Rédemptoristes ; 5. – Vers la création d’une nouvelle Préfecture Apostolique ; 6. – Fa- da N’Gourma et Niamey sont promus: 1959-1964 ; 7. – Le déploiement de l’activité missionnaire sur les deux territoires: 1965-1996 ; 8. – Retour à la case départ: Vice- Province du Burkina-Niger ; CONCLUSION GÉNÉRALE . -

Downloaded from Brill.Com08/31/2021 02:46:22AM

Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 07:30:01PM via free access AFRIKA FOCUS, Vol.3, Nr.3-4, I987, pp.237-285 CONGOLESE CHILDREN AT THE CONGO HOUSE IN COLWYN BAY (NORTH WALES, GREAT-BRITAIN), AT THE END OF THE 19th CENTURY. Unpublished documents. Zana Aziza ETAMBALA. Bursaal, K.U.Leuven Departement Moderne Geschiedenis Blijde Inkomststraat 21/5 B-3OOO Leuven CURRENT RESEARCH INTEREST : - the presence of Africans in Europe : 19-20 th century - the attitude of the Belgian Catholic Church towards Congo Free State SUMMARY In the present study we like to focus the attention on the presence of Congolese children at the Congo House in Colwyn Bay (North Wales, Great-Britain) during the last decade of the 19th century. The idea, which William Hughes conceived and which consisted of educating Congolese, in a first phase, and other African youth, in a second one, never received a just interest. The experiment of Hughes, a former baptist missionary, was a unique specimen for Great-Britain. Henry Morton Stanley and King Leopold II were a little bit involved in the successful start of this initiative. But this article has particularly in view an identification of the Congolese boys and girls who frequented the 'Congo House1! KEYWORDS : Colwyn Bay, Congolese children, Education, End of 19th century, W. Hughes Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 07:30:01PM via free access - 238 - INTRODUCTION During the last quarter of the 19th century, a lot of African children were sent out of the continent in order to receive a western education. Several young black boys and girls were taken to Belgium as well to Sweden, France, Germany, Italy, Malta, Great-Britain, Portugal, the United States and other countries (1). -

Don Bosco's Missionary Call and China

49-rss(215-294)studi.qxd 19-12-2006 14:38 Pagina 215 STUDI DON BOSCO’S MISSIONARY CALL AND CHINA Carlo Socol * Comparative Chronology: (A) General Events (B) Salesian Events 1839-1842 1st Opium War: 1841 Don Bosco ordained a priest Treaty of Nanking 1840/09 Martyrdom of Gabriel Perboyre 1845 1st edition of the Storia Ecclesiastica 1843 Cause of beatification of Perboyre begins 1853-1854 Japan opens to outside world 1859 Birth of the Salesian Society 1856 Martyrdom of Auguste Chapdelaine nd 1864 Comboni at Valdocco speaks 1858-1860 2 Opium War about Africa 1860/10 Treaty of Tientsin: French Protectorate 1869 The Holy See approves 1862 Canonization of Martyrs the Salesian Society of Nagasaki (1597) 1869 Mons. Lavigerie invites Salesians 1867 Beatification of Japanese Martyrs to Algeria (1617-32) 1869-70 3rd Edition of the 1867/09 Bishop E. Zanoli Storia Ecclesiastica of Hupei visits Valdocco 1870 Negotiations for San Francisco 1870/07 Comboni’s proposal for Cairo 1869-1870 1st Vatican Council 1871-72 1st missionary dream 1870 Bishops from China visit Valdocco 1873/10 Negotiations with 1870 Anti-foreign violence in Tientsin Msgr. T. Raimondi begin 1873/04 Consecration of Shrine of Zo-sé 1874/04 Salesian Constitutions approved st (Shanghai) 1875/11 1 Mission to Argentina 1874 Anti-foreign violence in Yunnan 1885/07 Dream about Angel of Arphaxad 1875 Anti-foreign violence in Szechwan 1886/04 Dream of Barcelona: 1885-1886 Persecution in Kiangsi Peking, Meaco… 1886/10 Conversation with A. Conelli in San Benigno 1886 Spiritual Testament 1888/1 Death of Don Bosco 1890 Conelli contacts Rondina about Macao * Salesiano, docente di Storia Ecclesiastica presso lo Holy Spirit Seminary di Hong Kong. -

1 Missionary Institutes in Europe: What

MISSIONARY INSTITUTES IN EUROPE: WHAT FUTURE? Introduction The title we have adopted may lead some readers to a hasty conclusion, even before reading the text: that we are concerned about the survival of missionary institutes due to the lack of missionary vocations in Europe. We say straight away that this is not our starting point, even if, as we shall see, the question of the general lack of missionary vocations in Europe cannot be avoided when we talk about missionary institutes in this continent. Our point of departure is another: the perception of an uprooting of missionary Institutes from the local Churches of Europe. On the one hand, it seems that the Churches of Europe no longer recognise missionary institutes as their actualised missionary expressions and, on the other hand, it seems that missionary institutes have moved away from the sensitivity and life of the European Churches. Obviously, we are only talking about missionary institutes in Europe and we are not referring to their situation in Africa (or America and Asia), for example, where their apostolic fruitfulness is evident and their insertion in the local Churches is easier and less problematic. This our starting point may not be shared and/or it may be rejected. But it is from this observation that we start. Faced with an evident lack of apostolic fruitfulness and creativity (which goes far beyond the question of vocations), we think that we cannot avoid the question of the rootedness, or lack thereof, of missionary institutes in the local Churches that have seen them born. We write in first person plural, because we want to capture the benevolence of the reader and involve him/her in the writing of the narrative, perhaps building their own, adopting the one proposed here or integrating it with different points of view. -

DOPPI- Monografie Aggiornato 20.06.2016

AUTORE TITOLO ANNO COLLOCAZIONE Istituto suore Elisabettine Atti del capitolo speciale 1968 1968 O.1.122 Flicoteaux E. Nuovo anno liturgico 1961 Z.7.82/83 "Civiltà Cattolica" 2009 2009 M.x.1 Typis polyglottis Vaticanis Acta synodalia sacrosancti concilii vat. II vol III period III pars II 1974 B.4.43 Lapide Cornelio Figura di san Paolo ossia Ideale della vita apostolica 1942 U.4.166 Tipografia Antoniana Atti del sinodo diocesano celebrato nel 1957 1957 A.3.30/31/32 Izard Raymond Adolescenza e vocazioni 1968 G.4.69/70/71 Pilli Fernando Atti della settimana cappellani militari RMNE 1992 B.5.90/91 Agostini Carlo Atti del V congresso Eucaristico- Padova 1958 C.6.27 A* Bibliotèque des exercices de St Ignace A 58 A* Bibliotèque des exercices de St Ignace CX 56 A* Adolescenza e penitenza 1969 A/1 Rops Daniel Al di là delle tenebre 1948 R.1.116 A* Al di là della vita 1981 A/2 A* Archivi ecclesiastici e mondo moderno 1991 A/1 A* Asseblea (L') del popolo di Dio 1964 A/2 A* Atlantino missioni 1960 A/2 Typis polyglottis Vaticanis Acta congressus catechistici internationalis MCML 1953 A.3.10 Agostini Carlo Atti del III congresso Eucaristico Diocesano di Padova 1940 C.6.26 Secretaria status Annuarium statisticum ecclesiae 1974 1976 A.3.6 A* Attività della santa sede 15 dic. 1942 - 15 dic.1943 1944 A/4 Secretaria status Annuarium statisticum ecclesiae 1975 1977 A.3.5 Secretaria status Annuarium statisticum ecclesiae 1983 1977 A.3.7 A* Almanacco dei bibliotecari italiani 1963 1963 A/5 A* Almanacco dei bibliotecari italiani 1964 1964 A/5 Guzzetti G.B. -

In Dialogue with the Comboni Missionary Sisters

DISCERNING A SPIRITUALITY FOR TRANSFORMATIVE MISSION: IN DIALOGUE WITH THE COMBONI MISSIONARY SISTERS by LAURA LEPORI submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR. MAGDALENE KARECKI CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. JNJ KRITZINGER JANUARY 2019 ii Summary This research seeks to acquire a deep understanding of how spirituality and mission correlate and shape each other. An initial review of missiological texts has revealed that spirituality is not often (nor explicitly) taken into consideration by missiologists. Likewise, mission generally does not occupy a central place within the academic discipline of spirituality. I contend that spirituality is the motor of mission and missiology and therefore cannot be only briefly mentioned or omitted from missiological discourse. This thesis explores this relationship with a specific focus on the Comboni Missionary Sisters. It explores the mission spirituality of their founder, Daniel Comboni, how this is taken up by the Comboni Missionary Sisters and how it shapes their lives and their being in mission. The research also aims to foster some transformations. It explores new ways for the Sisters to express their ways of being in mission in the context(s) in which they live, in order to be faithful to Comboni’s charism as well as to be a relevant presence today. The thesis proposes that mission spirituality be studied and lived by making use a Mission spirituality spiral. Its six dimensions are: spirituality, at the centre and all along the spiral; encounter with other(s) and with the context; context analysis; theological reflection (encounter with Scripture and Tradition); discernment for transformative ways of being in mission and reflexivity. -

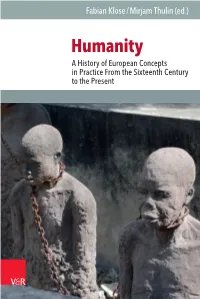

Humanity. a History of European Concepts in Practice From

Fabian Klose / Mirjam Thulin (ed.) Humanity A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Europäische Geschichte Mainz Abteilung für Abendländische Religionsgeschichte Abteilung für Universalgeschichte Edited by Irene Dingel and Johannes Paulmann Supplement 110 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Humanity A History of European Concepts in Practice From the Sixteenth Century to the Present Edited by Fabian Klose and Mirjam Thulin Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data available online: https://dnb.de. © 2016, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Theaterstraße 13, D-37073 Göttingen This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International license, at DOI 10.10139/9783666101458. For a copy of this license go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any use in cases other than those permitted by this license requires the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover picture: The Monument to the Slaves in the Grounds of Christ Church, Zanzibar. © Fabian Klose Typesetting: Vanessa Weber, Mainz Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlage | www.vandenhoeck-ruprecht-verlage.com ISSN 2197-1056 ISBN 978-3-666-10145-8 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 Acknowledgments The present volume grew out of the interdisciplinary conference “Human- ity – a History of European Concepts in Practice”, sponsored by the research group “Concepts of Humanity and Humanitarian Practice”, in October 2015 at the Leibniz Institute of European History in Mainz.