Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” in Japan and Its Impact on Post-War Animation Samuel Kaczorowski

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Leonardoelectronicalma

/ ____ / / /\ / /-- /__\ /______/____ / \ ________________________________________________________________ Leonardo Electronic Almanac volume 11, number 9, September 2003 ________________________________________________________________ ISSN #1071-4391 ____________ | | | CONTENTS | |____________| ________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL --------- < Art and Weightlessness: The MIR Campaign 2003 in Star City, by Annick Bureaud > FEATURES -------- < Art and Weightlessness: The MIR Campaign 2003 in Star City, by Annick Bureaud > < The Multidisciplinary Research Laboratory, by Nicola Triscott > < An Artist in Space - An Achievable Goal?, by Rob LaFrenais > < Projekt Atol Flight Operations and the MIR Network, by Marko Peljhan > < Contextualizing Zero-Gravity Art, by Roger Malina > < Art Critic in Microgravity, by Annick Bureaud > < May the Force Be with You, by Alex Adriaansens > < Transpermia - Dédalo Project, by Marcel.lí Antúnez Roca > < Open Sky and Microgravity, by Ewen Chardronnet > < Initial Report on the Pilot Study on the Military and Behavioral Preconditions for Permanent Habitation in Microgravity, by The Otolith Group (Kodwo Eshun, Richard Couzins, Anjalika Sagar) > < Filming in Microgravity, by Richard Couzins > < Kaplegraf 0g (Drops Orbits), by Vadim Fishkin, Livia Páldi > < The Celestial Vault, by Stefan Gec > LEONARDO REVIEWS ---------------- < Consciousness Reframed 2003: Art and Consciousness in the Post-Biological Era, Reviewed by Pia Tikka > < Coded Characters: Media Art by Jill Scott, Reviewed -

Odysseus the Hero of Ithaca Adapted from the Third Book of the Primary Schools of Athens, Greece by Mary E

ODYSSEUS THE HERO OF ITHACA ADAPTED FROM THE THIRD BOOK OF THE PRIMARY SCHOOLS OF ATHENS, GREECE BY MARY E. BURT Author of "Literary Landmarks," "Stories from Plato," "Story of the German Iliad," "The Child-Life Reading Study"; Editor of "Little Nature Studies"; Teacher in the John A. Browning School, New York City AND ZENAÏDE A. RAGOZIN Author of "The Story of Chaldea," "The Story of Assyria," "The Story of Media, Babylon, and Persia," "The Story of Vedic India"; Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, of the American Oriental Society, of the Société Ethnologique of Paris, etc. CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS NEW YORK CHICAGO BOSTON COPYRIGHT, 1898, BY CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS Printed in the United States of America To THE TEACHER WHOSE INTEGRITY AND PEDAGOGICAL SPIRIT HAVE CREATED A SCHOOL WHEREIN THE IDEAL MAY PROVE ITSELF THE PRACTICAL AND THOSE ENTHUSIASTIC PUPILS WHO LOVE THE LOYALTY AND BRAVERY OF ODYSSEUS THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED INTRODUCTION It has long been the opinion of many of the more progressive teachers of the United States that, next to Herakles, Odysseus is the hero closest to child-life, and that the stories from the "Odyssey" are the most suitable for reading-lessons. These conclusions have been reached through independent experiments not related to educational work in foreign countries. While sojourning in Athens I had the pleasure of visiting the best schools, both public and private, and found the reading especially spirited. I examined the books in use and found the regular reading- books to consist of the classic tales of the country, the stories of Herakles, Theseus, Perseus, and so forth, in the reader succeeding the primer, and the stories of Odysseus, or Ulysses, as we commonly call him, following as a third book, answering to our second or third reader. -

Keywords Studios 2019 Annual Report

Keywords Studios plc Studios Keywords Annual Report Annual Report and Accounts 2019 and Accounts 2019 Building our platform for growth Keywords Studios plc Overview Strategic report Annual Report and Accounts 2019 Pages 1–6 Pages 8–44 Highlights 1 Q&A with Andrew Day 8 At a glance 2 Chief Executive’s review 10 Investment summary 4 Market outlook 16 Chairman’s statement 6 Business model 18 Our strategy 22 Service line review 24 Our people, our culture 28 KPIs 34 Financial and operating review 36 Responsible Business report 40 Board engagement with our stakeholders 43 Principal risks and uncertainties 45 2019 Highlights Our vision is to be the world’s leading technical and creative services platform for the video games industry and beyond. At Keywords Studios (Keywords), we are using our passion for games, technology and media to create a global services platform. In 2019, we delivered strong growth as we invested in a strengthened and more diversified services platform. Alternative performance measures* The Group reports certain Alternative performance measures (APMs) to present the financial performance of the business which are not GAAP measures as defined by International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS). Management believes these measures provide valuable additional information for the users of the financial information to understand the underlying trading performance of the business. In particular, adjusted profit measures are used to provide the users of the accounts a clear understanding of the underlying profitability of the business over time. For full definitions and explanations of these measures and a reconciliation to the most directly referenceable IFRS line item, please see pages 135 to 143. -

Persephone in Hades

EDITORS John Blair, Un ivers ity of Geneva Karin Blair, United Nations, Geneva • Harry M. Bu ck, Wilso n College Rebecca Nisley, Silver Spring, Md. EDITORIAL Joyce L. Morrison ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE Beatrice Bruteau, Ph ilosophers' Exchange EDITORS Paul Cadrin, Un iversite Laval Carol Christ, San Diego State Un ivers ity Cornel ia Dimm itt, Georgetown University Linda Fish er, Harvard Un ivers ity Dan iel Goleman, Psychology Today • Rita Gross, Un ivers ity of Wisconsin-Eau Claire John Lindberg, Sh ippensburg State Co llege Linda Patricia, Kean College June Singer, Jungian Analyst, Ch icago CONSULTING Cynthia Allen, Florida State Un ivers ity EDITORS Martha Ashton, Udipi, India JoAnne Bauer, Hartford Seminary Foundation Su kumari Bhattacharji, Jadavpur Un iversity, Calcutta Barbara Blair, Fordham University Caro lyn Demaree, American Un iversity Richard and Florence Fa lk , Princeton University Naomi Goldenberg, Un iversity of Ot tawa • Josephine Harris, Wilson College Jean Houston, Foundation for Mind Research Thomas A Kapacinskas, Not re Da me Un iversity Susan Nichols, Dickinson Co llege Richard Rubenstein, Florida Stat e University PHOTOGRAPHY Veron ica Pera lta CONSULTANT CONSULTANT Raymond A. Ball inger DESIGNER • ANI MA, An Experiential Journal, is published by Conococheague Associates, Inc., adjacent to the Campus of Wilson College, 1053 Wilson Avenue, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania 17201 . Entire contents copyright © by Conococheague Associates, Inc., 1977. All rights reserved. Published semi-annually in celebration of the Spring and Fall Equinoxes. Address all correspond ence, including changes of address, to Harry M. Buck, 1053 Wilson Avenue, Chambersburg PA 17201 . Subscription price $7.50 annually, single copies $4.00. Unsolicited materials welcomed, but publisher assumes no responsibility for them. -

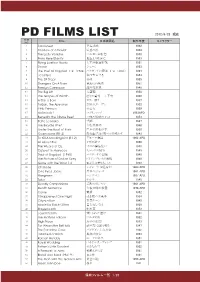

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Chaucer's Handling of the Proserpina Myth in The

CHAUCER’S HANDLING OF THE PROSERPINA MYTH IN THE CANTERBURY TALES by Ria Stubbs-Trevino A thesis submitted to the Graduate Council of Texas State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts with a Major in Literature May 2017 Committee Members: Leah Schwebel, Chair Susan Morrison Victoria Smith COPYRIGHT by Ria Stubbs-Trevino 2017 FAIR USE AND AUTHOR’S PERMISSION STATEMENT Fair Use This work is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, section 107). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of this material for financial gain without the author’s express written permission is not allowed. Duplication Permission As the copyright holder of this work I, Ria Stubbs-Trevino, authorize duplication of this work, in whole or in part, for educational or scholarly purposes only. DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my indomitable mother, Amber Stubbs-Aydell, who has always fought for me. If I am ever lost, I know that, inevitably, I can always find my way home to you. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are three groups of people I would like to thank: my thesis committee, my friends, and my family. I would first like to thank my thesis committee: Dr. Schwebel, Dr. Morrison, and Dr. Smith. The lessons these individuals provided me in their classrooms helped shape the philosophical foundation of this study, and their wisdom and guidance throughout this process have proven essential to the completion of this thesis. -

Summer Brings Classic Walt Disney and Warner Bros. Films, a Calder-Inspired Performance, and More Family-Friendly Offerings to the National Gallery of Art

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: May 31, 2012 Summer Brings Classic Walt Disney and Warner Bros. Films, a Calder-Inspired Performance, and More Family-Friendly Offerings to the National Gallery of Art Film still f rom The Tortoise and the Hare (1935, Walt Disney ), to be shown as part of the program Selections from the Silly Symphonies at National Gallery of Art on Saturday , July 7, Sunday , July 8, and Wednesday , July 11. Washington, DC—The National Gallery of Art welcomes summer with several free family-friendly activities, including an art-inspired performance in June and the popular Film Program for Children and Teens in July and August. On June 29, actor and visual artist Kevin Reese presents a one-man play inspired by the colorful, playful mobiles of Alexander Calder. In July, the Gallery presents Selections from the Silly Symphonies, a program of animated shorts produced by Walt Disney from 1929 to 1939. In August, Classic Looney Tunes features favorite cartoons from the Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies series. The film program presents a broad range of recently produced films selected for their appeal to youth and adult audiences, and helps foster an understanding of film as an art form. Age recommendations are intended to guide parents in selecting emotionally and intellectually stimulating films for their children. For a closer look at the Gallery's own works of art, families may explore the collection using the children's audio and video tour. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1 . See, for example, Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto’s review article “Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing Contemporary Japanese Animation. By Susan J. Napier” in The Journal of Asian Studies , 61(2), 2002, pp. 727–729. 2 . Key texts relevant to these thinkers are as follows: Gilles Deleuze, Cinema I and Cinema II (London: Athlone Press, 1989); Jacques Ranciere, The Future of the Image (London and New York: Verso, 2007); Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement Affect, Sensation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002); Slavoj Žižek, The Sublime Object of Ideology (London and New York: Verso, 1989); Steven Shaviro, The Cinematic Body (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993). 3 . This is a recurrent theme in The Anime Machine – and although Lamarre has a carefully nuanced approach to the significance of technology, he ultimately favours an engagement with the specificity of the technology as the primary starting point for an analysis of the “animetic” image: see Lamarre, 2009: xxi–xxiii. 4 . For a concise summing up of this point and a discussion of the distinction between creation and “fabrication” see Collingwood, 1938: pp. 128–131. 5 . Lamarre is strident critic of such tendencies – see The Anime Machine , p. xxviii & p. 89. 6 . “Culturalism” is used here to denote approaches to artistic products and artefacts that prioritize indigenous traditions and practices as a means to explain the artistic rationale of the content. While it is a valuable exercise in contextualization, there are limits to how it can account for creative processes themselves. 7 . Shimokawa Ōten produced Imokawa Mukuzo Genkanban no Maki (The Tale of Imokawa Mukuzo the Concierge ) which was the first animated work to be shown publicly – the images were retouched on the celluloid. -

Press Release

Press Release CaixaForum Madrid From July 19 to November 4, 2018 Until next November 4, ”la Caixa” Foundation presents a thrilling journey through the fantastic world of the company Walt Disney Animation Studios “The age-old kind of entertainment based on the classic fairy tale recognises no old, no young”. Through film, Walt Disney (Chicago, 1901 – Burbank, California, 1966) and his successive creative teams have brought popular and literary traditions to millions of spectators of all ages and all around the world. Since the 1930s, the American entertainment company has updated many classic stories, making them more accessible to audiences in every generation, always in the most delightful and entertaining fashion, continually interpreting the needs of a public seeking emotions and fantasy. Now, ”la Caixa” Foundation and the Walt Disney Animation Research Library join forces to present Disney. Art of Storytelling , an exhibition that explores the origins of some of the studio’s best-known films, all universal works in the art of animation. Spanning the period from Three Little Pigs (1933) to Frozen (2013), the show features 215 objects, including drawings, paintings, digital prints, screenplays and storyboards, as well as a number of film projections. Disney. Art of Storytelling . Organised and produced by : ”la Caixa” Foundation and the Walt Disney Animation Research Library. Curated by : The Walt Disney Animation Research Library curatorial team: Fox Carney, Tamara Khalaf, Kristen McCormick and Mary Walsh. Dates : From July 19 to November 4, 2018. Place : CaixaForum Madrid (Paseo del Prado, 36). @FundlaCaixa @CaixaForum #DisneyCaixaForum 2 Madrid, 18 July 2018. At CaixaForum Madrid today, Elisa Durán, Deputy General Manager of ”la Caixa” Banking Foundation; Isabel Fuentes, Director of CaixaForum Madrid; and the director of the Walt Disney Animation Research Library and co-curator of the exhibition, Mary Walsh; presents Disney. -

The Silly Symphonies Disney's First Fantasyland

X XIII THE SILLY SYMPHONIES DISNEY’S FIRST FANTASYLAND 3 PART I THE TIFFANY LINE 5 The Skeleton of an Idea 7 The Earliest Symphony Formula 9 Starting to Tell Tales Il Remaking Fairy Tales 18 Silly Toddlers and Their Families 19 Caste and Class in the Symphonies 21 An Exception to the Silly Rules: Three Little Pigs 22 Another Exception: Who Killed Cock Robin? 25 New Direction for the Symphonies at RKO 27 Ending in a Symphony Dream World 29 On a Final Note 31 PART Il PRODUCING THE SILLY SYMPHONIES 31 The ColurnbiaYears (1929-1932) 35 The United Artists Years (I932- 1937) 45 Disney’s RKO Radio Pictures (I937- 1939) 53 THE SKELETON DANCE (I929) I14 KING NEPTUNE (I932) a5 EL TERRIBLE TOREADOR (I 929) 115 BABES IN THE WOODS (I932) 58 SPRINGTIME (1929) I18 SANTA’S WORKSHOP (I 932) 50 HELL’S BELLS (I 929) 120 BIRDS IN THE SPRING (I933) 62 THE MERRY DWARFS (I929) I22 FATHER NOAH’S ARK (1933) 64 SUMMER (1930) i 24 THREE LITTLE PIGS (1933) 66 AUTUMN (I 930) I28 OLD KING COLE (1933) 58 CANNIBAL CAPERS (I 930) I30 LULLABY LAND (I 933) 7 NIGHT (I 930) I32 THE PIED PIPER (I933) 72 FROLICKING FISH (I 930) I34 THE CHINA SHOP (I933) É4 ARCTIC ANTICS (1930) I36 THE NIGHT BEFORE CHRISTMAS (I933) 76 MIDNIGHT IN ATOY SHOP (1930) I38 GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANTS (I 934) 78 MONKEY MELODIES (I 930) I49 THE BIG BAD WOLF (1934) no WINTER (I 930) i 42 FUNNY LITTLE BUNNIES (1934) 82 PLAYFUL PAN (I 930) I44 THE FLYING MOUSE (I 934) 84 BIRDS OF A FEATHER (I93 I) I46 THE WISE LITTLE HEN (I934) 86 MOTHER GOOSE MELODIES (I 93 I) 148 PECULIAR PENGUINS (1934) 88 THE CHINA PLATE -

Anime in America, Disney in Japan: the Global Exchange of Popular Media Visualized Through Disney’S “Stitch”

Anime in America, Disney in Japan: The Global Exchange of Popular Media Visualized through Disney’s “Stitch” Nicolette Lucinda Pisha Asheville, North Carolina Bachelor of Arts, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2008 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College^oEWilliam and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary January, 2010 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts NicoletteAucinda Pisha Approved ®y the £r, 2009 Associate Professor Arthur Knight, American Studies and English The College of William and Mary,, Visiting Assistant Professor Timothy Barnard, American Studies The College of William and Mary Assistant Professor Hiroshi Kitamura, History The College of William and Mary ABSTRACT PAGE My thesis examines the complexities of Disney’s Stitch character, a space alien that appeals to both American and Japanese audiences. The substitutive theory of Americanization is often associated with the Disney Company’s global expansion; however, my work looks at this idea as multifaceted. By focusing on the Disney Company’s relationship with the Japanese consumer market, I am able to provide evidence of instances when influence from the local Japanese culture appears in both Disney animation and products. For example, Stitch contains many of the same physical characteristics found in both Japanese anime and manga characters, and a small shop selling local Japanese crafts is located inside the Tokyo Disneyland theme park. I completed onsite research at Tokyo Disneyland and learned about city life in Tokyo.