Progress, Challenges and Opportunities for Biodiversity Accounting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Record of Spencer's Skink Pseudemoia Spenceri from The

Contributions A record of Spencer’s Skink Pseudemoia spenceri from the Victorian Volcanic Plain Peter Homan School of Life & Physical Sciences, RMIT University, GPO Box 2476V, Melbourne, Victoria 3001. Email: [email protected] Abstract During a survey of vertebrate fauna at a site in Yan Yean, north of Melbourne on the Victorian Volcanic Plain, a small population of Spencer’s Skink Pseudemoia spenceri was found inhabiting a heritage dry stone fence. Spencer’s Skink is normally found in wet schlerophyll forest and cool temperate environments, and the species is not considered a grassland inhabitant. There are no other records of Spencer’s Skink occurring in any part of the Victorian Volcanic Plain. (The Victorian Naturalist 128(3) 2011, 106-110) Keywords: Spencer’s Skink Pseudemoia spenceri, Volcanic Plain, grasslands, dry stone fences. Introduction The Growling Frog Golf Course (GFGC) is the dry stone fences as habitat. These include situated on the Victorian Volcanic Plain in Yan Large Striped Skink Ctenotus robustus, Bou- Yean (37° 33'S, 145° 04'E), approximately 33 km gainville’s Skink Lerista bougainvillii, Lowland north-north-east of the Melbourne Central Copperhead Austrelaps superbus, Little Whip Business District. The course was established Snake Parasuta flagellum, Southern Bullfrog in 2005 by the City of Whittlesea under strict Limnodynastes dumerilii and Spotted Marsh environmental conditions that required the Frog Limnodynastes tasmaniensis. preservation of important natural and herit- Record of Spencer’s Skink Pseudemoia spen- age features. These included protection of ceri inhabiting dry stone fence stony knolls, ephemeral wetlands and an area On 26 March 2010, staff and students from the of Plains Grassy Woodland; preservation of all School of Life and Physical Sciences, RMIT River Red Gums Eucalyptus camaldulensis and University, visited the GFGC to examine a hab- several rare plant species; and retention of her- itat enhancement program near the dry stone itage dry stone fences. -

A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes)

Galliform Baraminology 1 Running Head: GALLIFORM BARAMINOLOGY A Baraminological Analysis of the Land Fowl (Class Aves, Order Galliformes) Michelle McConnachie A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2007 Galliform Baraminology 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Timothy R. Brophy, Ph.D. Chairman of Thesis ______________________________ Marcus R. Ross, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Harvey D. Hartman, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Judy R. Sandlin, Ph.D. Assistant Honors Program Director ______________________________ Date Galliform Baraminology 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, without Whom I would not have had the opportunity of being at this institution or producing this thesis. I would also like to thank my entire committee including Dr. Timothy Brophy, Dr. Marcus Ross, Dr. Harvey Hartman, and Dr. Judy Sandlin. I would especially like to thank Dr. Brophy who patiently guided me through the entire research and writing process and put in many hours working with me on this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family for their interest in this project and Robby Mullis for his constant encouragement. Galliform Baraminology 4 Abstract This study investigates the number of galliform bird holobaramins. Criteria used to determine the members of any given holobaramin included a biblical word analysis, statistical baraminology, and hybridization. The biblical search yielded limited biosystematic information; however, since it is a necessary and useful part of baraminology research it is both included and discussed. -

Alpine Skinks

AUSTRALIAN THREATENED SPECIES ALPINE SKINKS Alpine Water Skink Eulamprus kosciuskoi; Conservation Status (Victoria): Critically Endangered* Alpine She-oak Skink Cyclodomorphus praealtus ; Conservation Status (Victoria): Endangered* *Advisory List of Rare or Threatened Vertebrate Fauna, Department of Sustainability and Environment (2003) and listed under Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 What do they look like? Australia and its external territories occur nowhere else in the world. Generally, skinks (family Scincidae ) are small- • to medium-sized lizards. The reptile fauna of the alpine region of Victoria is dominated by skinks (in terms of Two threatened alpine skinks are the Alpine she- numbers), although one dragon lizard and oak skink — a relatively broad-headed, short- three venomous snakes also occur in this legged, smooth-scaled lizard and the Alpine area. • water skink – a robust skink, with a body length Two other Victorian alpine skinks, the of up to 80 millimetres. Alpine bog skink ( Pseudemoia cryodroma) and the Guthega skink ( Egernia guthega) are also threatened with extinction in Where do they live? Victoria. Although some alpine skink species also occur in • The Alpine skinks give birth to live young. other parts of Victoria, several are endemic to the • A large proportion of the known range of the Alps. Nearly half of the skinks are officially Alpine she-oak skink occurs within, or listed as threatened by the Victorian Department adjacent to, the Mt Hotham and Falls Creek of Sustainability and Environment. Some of Alpine Resorts. these reptiles are abundant and readily observed, whilst others are rare and/or secretive. The Alpine water skink is restricted to sphagnum bogs, streamsides and wet heath vegetation. -

A Molecular Phylogeny of the Peacock-Pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron Spp.) Indicates Loss and Reduction of Ornamental Traits and Display Behaviours

Biological Journal of the Linnean Society (2001), 73: 187–198. With 3 figures doi:10.1006/bijl.2001.0536, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on A molecular phylogeny of the peacock-pheasants (Galliformes: Polyplectron spp.) indicates loss and reduction of ornamental traits and display behaviours REBECCA T. KIMBALL1,2∗, EDWARD L. BRAUN1,3, J. DAVID LIGON1, VITTORIO LUCCHINI4 and ETTORE RANDI4 1Department of Biology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA 2Department of Evolution, Ecology and Organismal Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 3Department of Plant Biology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 4Istituto Nazionale per la Fauna Selvatica, via Ca` Fornacetta 9, 40064 Ozzano dell’Emilia (BO), Italy Received 4 September 2000; accepted for publication 3 March 2001 The South-east Asian pheasant genus Polyplectron is comprised of six or seven species which are characterized by ocelli (ornamental eye-spots) in all but one species, though the sizes and distribution of ocelli vary among species. All Polyplectron species have lateral displays, but species with ocelli also display frontally to females, with feathers held erect and spread to clearly display the ocelli. The two least ornamented Polyplectron species, one of which completely lacks ocelli, have been considered the primitive members of the genus, implying that ocelli are derived. We examined this hypothesis phylogenetically using complete mitochondrial cytochrome b and control region sequences, as well as sequences from intron G in the nuclear ovomucoid gene, and found that the two least ornamented species are in fact the most recently evolved. Thus, the absence and reduction of ocelli and other ornamental traits in Polyplectronare recent losses. -

A Review of Natural Values Within the 2013 Extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area

A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Nature Conservation Report 2017/6 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Hobart A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area Jayne Balmer, Jason Bradbury, Karen Richards, Tim Rudman, Micah Visoiu, Shannon Troy and Naomi Lawrence. Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, September 2017 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (World Heritage Program). Australian Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Tasmanian or Australian Governments. ISSN 1441-0680 Copyright 2017 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Published by Natural Values Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart, Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph of Eucalyptus regnans tall forest in the Styx Valley: Rob Blakers Cite as: Balmer, J., Bradbury, J., Richards, K., Rudman, T., Visoiu, M., Troy, S. and Lawrence, N. 2017. A review of natural values within the 2013 extension to the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2017/6, Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Hobart. -

The Victorian Naturalist

The Volume 128 (3) June 2011 Published by The Field Naturalists Club of Victoria since 1884 From the Editors Over the long history of The Victorian Naturalist the journal has continued to provide a record of studies by both scientifically-trained and amateur researchers of what was observed at a given time and place. These records have often provided a valuable basis, through comparison, for observing change over time in aspects of natural history. The current issue maintains these traditions, with the papers illustrating such changes. We publish here the first study of the decapods of the Pilliga Scrub in New South Wales, details of an extension of the Victorian range of a species of skink, and observations on an undescribed species of fungi. The range of subject matter in these papers also highlights, once again, the diversity that exists of both interest and study regarding the natural world. The Victorian Naturalist is published six times per year by the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria Inc Registered Office: FNCV, 1 Gardenia Street, Blackburn, Victoria 3130, Australia. Postal Address: FNCV, Locked Bag 3, Blackburn, Victoria 3130, Australia. Phone/Fax (03) 9877 9860; International Phone/Fax 61 3 9877 9860. email: [email protected] www.fncv.org.au Patron: His Excellency, the Governor of Victoria Address correspondence to: The Editors, The Victorian Naturalist, Locked Bag 3, Blackburn, Victoria, Australia 3130. Phone: (03) 9877 9860. Email: [email protected] The opinions expressed in papers and book reviews published in The Victorian Naturalist are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the FNCV. -

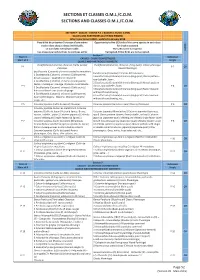

Section P, Quales and Partridges.Cdr

SECTIONS ET CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTIONS AND CLASSES O.M.J./C.O.M. SECTION P - CAILLES - COLINS P.E. ( BAGUES 1 ET/OU 2 ANS) QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES (1/2 YEARS RINGED) Mise à jour Janvier 2018 - updated in January 2018 Possibilité de présenter 5 oiseaux d'une même Opportunity to five (5) birds of the same species in each class C A espèce dans chaque classe individuelle. for singles accepted GE Le nom lan est indispensable. The Lan name is required. S Les oiseaux panachés-frisés ne sont pas admis Variegated-frilled birds are not accepted. Secon P Stam 4 Individuel CAILLES - COLINS DOMESTIQUES Stam of 4 Single QUAILS AND PARTRIDGES DOMESTIC Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) Excalfactoria(coturnix) chinensis. (King quail) Classic phenoype P 1 P 2 O1 Classique Classic Phenotype Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis toutes les mutaons Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis All mutaons: 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 1 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Classic paern : Dessin sauvage : Opale,Brune etIsabelle . opal,Isabelle , fawn.. 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 2 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Mosaïc paern Facteur mosaïque : sauvage, Opale,Brune etIsabelle P 3 classic, opal,Isabelle , fawn. P 4 O1 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 3 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (King quail) Factor melanic Patron mélanisé sans dessin de gorge without throat drawing 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis (Caille peinte) 4 Excalfactoria (Coturnix) chinensis -

Comparison of Cytochrome B Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis

287 Comparison of Cytochrome b Region Among Chinese Painted Quail, Wild-Strain Quail, and White Broiler Chicken Based on PCR-RFLP Analysis Xiang-Jun SHEN1),Hidenori SUZUKI2)*, Masaoki TSUDZUKI3), Shin'ichiITO2) and Takao NAKAMURA2)** 1)The United Graduate School of AgriculturalScience , 2)Faculty of Agriculture, GifuUniversity, Gifu 501-1193 3)Faculty of AppliedBiological Science , Hiroshima University,Higashi-Hiroshima 739-8528 PCR-RFLPanalysis was used to examine 1,075 bp cytochromeb (Cyt b) region of mtDNAineach of 20birds of Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis), wild-strain Japanesequail (Coturnix japonica), and white broiler chicken (Gallus gallus). The total Cytb ampliconwas digested with 10 restriction endonucleases, andits electrophoretic patternwas investigated. Ten kinds of restrictionenzyme digestions were identical among20 individuals ineach of the three species. No variation was observed in the 10 kindsof enzymedigestions among different individuals within the threespecies in- vestigated.The different specific electrophoretic patterns, haplotypes, and total restric- tionfragments were observed in eachof the three species belonging tothe same family Phasianidae.The result representatives the evolutionarygenetic characteristics of RFLPof cytochromeb region in thethree different species, and indicated the genetic diversityamong the three genuses of the family Phasianidae, and genetic identity within eachof thespecies. The result could be used for the identification of different species withinfamily Phasianidae and as a referenceofphysical map for cytochrome b gene. (Jpn.Poult. Sci., 36: 287-294, 1999) Keywords:PCR-RFLP, cytochrome b,Excalfactoria chinensis, Coturnix japonica, Gallus gallus Introduction Chinesepainted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs to the orderGalliformes, family Phasianidae,and genus Excalfactoria,(YAMASHINA, 1986). Japanese quail belongsto the samefamily Phasianidae, a different genus Coturnix (CRAWFORD, 1990). -

Glossy Grass Skink

Threatened Species Link www.tas.gov.au SPECIES MANAGEMENT PROFILE Pseudemoia rawlinsoni Glossy Grass Skink Group: Chordata (vertebrates), Reptilia (reptiles), Squamata (Snakes, Lizards and Skinks), Scincidae Status: Threatened Species Protection Act 1995: rare Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999: Not listed Endemic Found in Tasmania and elsewhere Status: In Tasmania, the Glossy Grass Skink (Pseudemoia rawlinsoni), a ground-dwelling lizard, occurs in swampy and wetland sites. It has a widespread but scattered distribution in Tasmania, known from locations on the east coast, north coast, inland near Cradle Mountain and Cape Barren Island. The species has probably suffered a historical decline in range, and continues to be threatened by several processes. These include clearing and drainage of swampy habitats for agriculture, urban encroachment, forestry operations, and alterations to flow regimes and water quality. Protection of known sites and potential habitat from such activities is the key requirement for the species. A complete species management profile is not currently available for this species. Check for further information on this page and any relevant Activity Advice. Key Points Important: Is this species in your area? Do you need a permit? Ensure you’ve covered all the issues by checking the Planning Ahead page. Important: Different threatened species may have different requirements. For any activity you are considering, read the Activity Advice pages for background information and important advice about managing around the needs of multiple threatened species. Habitat 'Habitat' refers to both known habitat for the species (i.e. in or near habitat where the species has been recorded) and potential habitat (i.e. -

Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome B Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria C

-Rapid Communication- Primer Design and Sequence Information for Cytochrome b Gene in the Chinese Painted Quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) Xiang-Jun SHEN, Masaoki TSUDZUKIa, Takao NAKAMURAb The United Graduate School of Agricultural Science, Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan Faculty of Applied Biological Science, Hiroshima University, Higashi-Hiroshima-shi 739-8528,a Japan bFaculty of Agriculture , Gifu University, Gifu-shi 501-1193, Japan (Received April 21, 1999; Accepted May 15, 1999) Abstract In accordance with the chicken and quail mitochondrialDNA sequences,three pairs of primers encompassing light and heavy strand (L14832, L15269, L15500, H15924, H15497, and H16207) with high specificity were designed, synthesized, and used for amplification and sequencing of cytochrome b (Cyt b) gene. The PCR products were sequenced by the direct-sequencing method. The Chinese painted quail cytochrome b gene consisted of 1,143bp nucleotides (base composition: 327 A; 399 C; 281 T and 136 G), encoded for a 380 amino acid sequence, and showed 89.0%, 86.4%, and 86.2%, homology with nucleotide sequences of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The homology of the amino acid sequence of the cytochrome b gene of Chinese painted quail showed 98.2%, 95.3%, and 95.3% with those of Japanese quail, silky fowl, and White Leghorn chicken, respectively. The sequencesreported in this paper have been depositedin the GenBank database(Accession No. AF109217). Animal Science Journal 70 (4): 240-242,1999 Key words: Chinese painted quail,Excalfactoria chinensis, Cytochromeb, Sequence,Homology Chinese painted quail (Excalfactoria chinensis) belongs the test: to the order Galliformes, family Phasianidae, genus (1) L14832: 5'-TACCTGGGTTCCTTCGCCCT-3' Excalfactoria5),and it is the smallest species in the family (2) H15497: 5'-TGTAGGAAGGTGAGTGGAT-3' Phasianidae. -

Preliminary Flora and Fauna Assessment - Penshurst Wind Farm Final.Doc

Preliminary Flora and Fauna Assessment - Penshurst Wind Farm Project: 09 - 055 Prepared for: RES Australia Ecology Australia Pty Ltd Flora and Fauna Consultants www.ecologyaustralia.com.au [email protected] 88B Station Street, Fairfield, Victoria, Australia 3078 Tel: (03) 9489 4191 Fax: (03) 9481 7679 © 2009 Ecology Australia Pty Ltd This publication is copyright. It may only be used in accordance with the agreed terms of the commission. Except as provided for by the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of Ecology Australia Pty Ltd. Document information This is a controlled document. Details of the document ownership, location, distribution, status and revision history are listed below. All comments or requests for changes to content should be addressed to the document owner. Bioregion: Victorian Volcanic Plain Owner Ecology Australia Author Andrew McMahon and Ruth Marr J:\CURRENT PROJECTS\Penshurst Windfarm 09- Location 55\report\Preliminary Flora and Fauna Assessment - Penshurst Wind Farm Final.doc Distribution Simon Kerrison RES Australia Document History Status Changes By Date Draft 0.1 First Draft Andrew McMahon 22/7/09 and Ruth Marr Final Final Andrew McMahon 10/08/09 and Ruth Marr Final - ii Preliminary Flora and Fauna Assessment - Penshurst Wind Farm Contents Summary 1 1 Introduction 1 2 Study Area 3 3 Methods 5 3.1 Information Review 5 3.2 Preliminary site assessment 6 3.3 Liaison -

Download Article (PDF)

PERNo. 330 i s (Aves)· t e Co ·0 0 t e rv yo dia • IVE • RVEYO ' OCCASIONAL PAPER No. 330 RECORDS OF THE ZOOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA Catalogue of Type Specilllens (Aves) in the National Zoological Collection of the Zoological Survey of India R. SAKTHIVE"L*, B.B. DUTrA & K. VENKATARAMAN** (*[email protected] & [email protected]; **[email protected]) Zoological Survey of India M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 Zoological Survey of India Kolkata CITATION Sakthivel, R., Dutta, B.B. and Venkataraman, K. 2011. Catalogue of type specimens (Aves) in the National Zoological Collection of the Zoological Survey of India, Rec. zoc;>l. Surv. India, Occ. Paper No. 330 : 1-174 (Published by the Director, Zool. Surv. India, Kolkata) Published : November, 2011 ISBN 978-81-8171-294-3 © Gout. ofIndia, 2011 All RIGHTS RESERVED • No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. • This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher's consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. • The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page. Any revised price indicated by a rubber stomp or by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. PRICE India : ~ 525.00 Foreign: $ 35; £ 25 Published at the Publication Division by the Director, Zoological Survey of India, M-Block, New Alipore, Kolkata-700 053 and printed at Calcutta Repro Graphics, Kolkata-700 006 CONTENTS INfRODUcrION .................................................................................................................