Regulated Proteolysis of a Cross-Link–Specific Peptidoglycan Hydrolase Contributes to Bacterial Morphogenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ubiquitin-Mediated Proteolysis the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2004 Is

Advanced information on the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 6 October 2004 Information Department, P.O. Box 50005, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden Phone: +46 8 673 95 00, Fax: +46 8 15 56 70, E-mail: [email protected], Website: www.kva.se Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis The Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 2004 is shared between three scientists who have made fundamental discoveries concerning how cells regulate the breakdown of intracellular proteins with extreme specificity as to target, time and space. Aaron Ciechanover, Avram Hershko and Irwin Rose together discovered ubiquitin- mediated proteolysis, a process where an enzyme system tags unwanted proteins with many molecules of the 76-amino acid residue protein ubiquitin. The tagged proteins are then transported to the proteasome, a large multisubunit protease complex, where they are degraded. Numerous cellular processes regulated by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis include the cell cycle, DNA repair and transcription, protein quality control and the immune response. Defects in this proteolysis have a causal role in many human diseases, including a variety of cancers. Fig. 1 Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis and its many biological functions 2 Introduction Eukaryotic cells, from yeast to human, contain some 6000 to 30000 protein-encoding genes and at least as many proteins. While much attention and research had been devoted to how proteins are synthesized, the reverse process, i.e. how proteins are degraded, long received little attention. A pioneer in this field was Schoenheimer, who in 1942 published results from isotope tracer techniques indicating that proteins in animals are continuously synthesized and degraded and therefore are in a dynamic state (Schoenheimer, 1942). -

Insights Into Clpxp Proteolysis: Heterooligomerization and Partial Deactivation Cite This: Chem

Chemical Science View Article Online EDGE ARTICLE View Journal | View Issue Insights into ClpXP proteolysis: heterooligomerization and partial deactivation Cite this: Chem. Sci.,2017,8,1592 enhance chaperone affinity and substrate turnover in Listeria monocytogenes† a a a b a Dora´ Balogh,‡ Maria Dahmen,‡ Matthias Stahl, Marcin Poreba, Malte Gersch,§ Marcin Dragb and Stephan A. Sieber*a Caseinolytic proteases (ClpP) are important for recognition and controlled degradation of damaged proteins. While the majority of bacterial organisms utilize only a single ClpP, Listeria monocytogenes expresses two isoforms (LmClpP1 and LmClpP2). LmClpPs assemble into either a LmClpP2 homocomplex or a LmClpP1/2 heterooligomeric complex. The heterocomplex in association with the chaperone ClpX, exhibits a boost in proteolytic activity for unknown reasons. Here, we use a combined chemical and biochemical strategy to unravel two activation principles of LmClpPs. First, determination Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported Licence. of apparent affinity constants revealed a 7-fold elevated binding affinity between the LmClpP1/2 heterocomplex and ClpX, compared to homooligomeric LmClpP2. This tighter interaction favors the formation of the proteolytically active complex between LmClpX and LmClpP1/2 and thereby accelerating the overall turnover. Second, screening a diverse library of fluorescent labeled peptides and proteins with various ClpP mutants allowed the individual analysis of substrate preferences for both isoforms within the heterocomplex. In addition to Leu and Met, LmClpP2 preferred a long aliphatic chain (2-Aoc) in the P1 position for cleavage. Strikingly, design and synthesis of a corresponding 2-Aoc chloromethyl ketone inhibitor resulted in stimulation of proteolysis by 160% when LmClpP2 was partially Received 2nd August 2016 This article is licensed under a alkylated on 20% of the active sites. -

Changes in Proteolysis in Fermented Milk Produced by Streptococcus Thermophilus in Co-Culture with Lactobacillus Plantarum Or Bifidobacterium Animalis Subsp

molecules Article Changes in Proteolysis in Fermented Milk Produced by Streptococcus thermophilus in Co-Culture with Lactobacillus plantarum or Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis During Refrigerated Storage Sining Li 1,2 , Shanhu Tang 1,*, Qiang He 2,*, Jiangxiao Hu 1 and Jing Zheng 1 1 College of Life Science and Technology, Southwest Minzu University, Chengdu 610041, China; [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (J.H.); [email protected] (J.Z.) 2 College of Biomass Science and Engineering, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610065, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (Q.H.); Tel.: +86-28-85528876 (S.T.); +86-28-85468323 (Q.H.) Received: 1 September 2019; Accepted: 13 October 2019; Published: 15 October 2019 Abstract: Proteolysis in fermented milk, a complex and dynamic process, depends on the starter cultures used. This study aimed to evaluate the influence of Lactobacillus plantarum or Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis, or both, co-fermented with Streptococcus thermophilus, on the changes in the proteolysis profile of fermented milk during 21-day storage at 4 ◦C, including the pH value, proteolytic degree, protease activity, aminopeptidase activity, free amino acid content, and electrophoresis performance. The results showed that the treatments with co-cultures exhibited a higher amount of free amino groups and neutral protease activity at an extracellular level, whereas lower pH values and aminopeptidase activities towards the six substrates at an intracellular level than the ones with a single-strain of S. thermophilus over the refrigerated storage were observed. In co-fermentation with S. thermophilus, B. animalis subsp. lactis did not significantly affect the concentrations of most free amino acids, while contributions of L. -

1 No. Affymetrix ID Gene Symbol Genedescription Gotermsbp Q Value 1. 209351 at KRT14 Keratin 14 Structural Constituent of Cyto

1 Affymetrix Gene Q No. GeneDescription GOTermsBP ID Symbol value structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 1. 209351_at KRT14 keratin 14 filament, epidermis development <0.01 biological process unknown, S100 calcium binding calcium ion binding, cellular 2. 204268_at S100A2 protein A2 component unknown <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 3. 33323_r_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 4. 33322_i_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 5. 201820_at KRT5 keratin 5 filament, epidermis development <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 6. 209125_at KRT6A keratin 6A filament, ectoderm development <0.01 regulation of progression through cell cycle, extracellular space, cytoplasm, cell proliferation, protein kinase C inhibitor activity, protein domain specific 7. 209260_at SFN stratifin/14-3-3σ binding <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, intermediate 8. 213680_at KRT6B keratin 6B filament, ectoderm development <0.01 receptor activity, cytosol, integral to plasma membrane, cell surface receptor linked signal transduction, sensory perception, tumor-associated calcium visual perception, cell 9. 202286_s_at TACSTD2 signal transducer 2 proliferation, membrane <0.01 structural constituent of cytoskeleton, cytoskeleton, intermediate filament, cell-cell adherens junction, epidermis 10. 200606_at DSP desmoplakin development <0.01 lectin, galactoside- sugar binding, extracellular binding, soluble, 7 space, nucleus, apoptosis, 11. 206400_at LGALS7 (galectin 7) heterophilic cell adhesion <0.01 2 S100 calcium binding calcium ion binding, epidermis 12. 205916_at S100A7 protein A7 (psoriasin 1) development <0.01 S100 calcium binding protein A8 (calgranulin calcium ion binding, extracellular 13. -

Protacs: Chimeric Molecules That Target Proteins to the Skp1–Cullin–F Box Complex for Ubiquitination and Degradation

Protacs: Chimeric molecules that target proteins to the Skp1–Cullin–F box complex for ubiquitination and degradation Kathleen M. Sakamoto*†‡, Kyung B. Kim§, Akiko Kumagai†, Frank Mercurio¶, Craig M. Crews§, and Raymond J. Deshaies†‡ʈ *Department of Pediatrics and Pathology, Mattel Children’s Hospital at University of California Los Angeles, University of California Los Angeles School of Medicine, Gwynn Hazen Cherry Memorial Laboratories, and Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, Los Angeles, CA 90095-1752; †Division of Biology, and ʈHoward Hughes Medical Institute, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91125; §Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520; and ¶Signal Division, Celgene Pharmaceuticals, La Jolla, CA 92121 Communicated by Alexander Varshavsky, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, May 10, 2001 (received for review March 29, 2001) The intracellular levels of many proteins are regulated by ubiq- to be the primary target of the potent angiogenesis inhibitors uitin-dependent proteolysis. One of the best-characterized en- fumagillin and ovalicin (OVA; refs. 7 and 8). Both of these zymes that catalyzes the attachment of ubiquitin to proteins is a compounds inhibit MetAP-2 by covalently binding His-231 in the ubiquitin ligase complex, Skp1-Cullin-F box complex containing active site. The consequent reduction in MetAP-2 activity is Hrt1 (SCF). We sought to artificially target a protein to the SCF thought to block endothelial cell proliferation by causing p53- complex for ubiquitination and degradation. To this end, we tested dependent arrest in the G1 phase of the cell cycle (9). Impor- methionine aminopeptidase-2 (MetAP-2), which covalently binds tantly, MetAP-2 is not known to be ubiquitinated or a substrate the angiogenesis inhibitor ovalicin. -

Proteolytic Cleavage—Mechanisms, Function

Review Cite This: Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 1137−1168 pubs.acs.org/CR Proteolytic CleavageMechanisms, Function, and “Omic” Approaches for a Near-Ubiquitous Posttranslational Modification Theo Klein,†,⊥ Ulrich Eckhard,†,§ Antoine Dufour,†,¶ Nestor Solis,† and Christopher M. Overall*,†,‡ † ‡ Life Sciences Institute, Department of Oral Biological and Medical Sciences, and Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada ABSTRACT: Proteases enzymatically hydrolyze peptide bonds in substrate proteins, resulting in a widespread, irreversible posttranslational modification of the protein’s structure and biological function. Often regarded as a mere degradative mechanism in destruction of proteins or turnover in maintaining physiological homeostasis, recent research in the field of degradomics has led to the recognition of two main yet unexpected concepts. First, that targeted, limited proteolytic cleavage events by a wide repertoire of proteases are pivotal regulators of most, if not all, physiological and pathological processes. Second, an unexpected in vivo abundance of stable cleaved proteins revealed pervasive, functionally relevant protein processing in normal and diseased tissuefrom 40 to 70% of proteins also occur in vivo as distinct stable proteoforms with undocumented N- or C- termini, meaning these proteoforms are stable functional cleavage products, most with unknown functional implications. In this Review, we discuss the structural biology aspects and mechanisms -

Intrinsic Evolutionary Constraints on Protease Structure, Enzyme

Intrinsic evolutionary constraints on protease PNAS PLUS structure, enzyme acylation, and the identity of the catalytic triad Andrew R. Buller and Craig A. Townsend1 Departments of Biophysics and Chemistry, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD 21218 Edited by David Baker, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, and approved January 11, 2013 (received for review December 6, 2012) The study of proteolysis lies at the heart of our understanding of enzyme evolution remain unanswered. Because evolution oper- biocatalysis, enzyme evolution, and drug development. To un- ates through random forces, rationalizing why a particular out- derstand the degree of natural variation in protease active sites, come occurs is a difficult challenge. For example, the hydroxyl we systematically evaluated simple active site features from all nucleophile of a Ser protease was swapped for the thiol of Cys at serine, cysteine and threonine proteases of independent lineage. least twice in evolutionary history (9). However, there is not This convergent evolutionary analysis revealed several interre- a single example of Thr naturally substituting for Ser in the lated and previously unrecognized relationships. The reactive protease catalytic triad, despite its greater chemical similarity rotamer of the nucleophile determines which neighboring amide (9). Instead, the Thr proteases generate their N-terminal nu- can be used in the local oxyanion hole. Each rotamer–oxyanion cleophile through a posttranslational modification: cis-autopro- hole combination limits the location of the moiety facilitating pro- teolysis (10, 11). These facts constitute clear evidence that there ton transfer and, combined together, fixes the stereochemistry of is a strong selective pressure against Thr in the catalytic triad that catalysis. -

Activity-Based Profiling of Proteases

BI83CH11-Bogyo ARI 3 May 2014 11:12 Activity-Based Profiling of Proteases Laura E. Sanman1 and Matthew Bogyo1,2,3 Departments of 1Chemical and Systems Biology, 2Microbiology and Immunology, and 3Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California 94305-5324; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014. 83:249–73 Keywords The Annual Review of Biochemistry is online at biochem.annualreviews.org activity-based probes, proteomics, mass spectrometry, affinity handle, fluorescent imaging This article’s doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060713-035352 Abstract Copyright c 2014 by Annual Reviews. All rights reserved Proteolytic enzymes are key signaling molecules in both normal physi- Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2014.83:249-273. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org ological processes and various diseases. After synthesis, protease activity is tightly controlled. Consequently, levels of protease messenger RNA by Stanford University - Main Campus Lane Medical Library on 08/28/14. For personal use only. and protein often are not good indicators of total protease activity. To more accurately assign function to new proteases, investigators require methods that can be used to detect and quantify proteolysis. In this review, we describe basic principles, recent advances, and applications of biochemical methods to track protease activity, with an emphasis on the use of activity-based probes (ABPs) to detect protease activity. We describe ABP design principles and use case studies to illustrate the ap- plication of ABPs to protease enzymology, discovery and development of protease-targeted drugs, and detection and validation of proteases as biomarkers. 249 BI83CH11-Bogyo ARI 3 May 2014 11:12 gens that contain inhibitory prodomains that Contents must be removed for the protease to become active. -

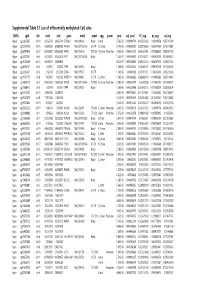

Supplementary Table S1 Kim Et Al.Xlsx

Supplemental Table S1. List of differentially methylated CpG sites DMRs cgid chr start end gene nmid annot cpg prom pval adj. pval FC_avg nc_avg cd_avg Hyper cg12827637 chr14 69256790 69256791 ZFP36L1 NM_004926 Body Island . 5.76E-05 0.000989714 4.465355492 0.06419878 0.287016909 Hyper cg02072495 chr15 60689284 60689285 ANXA2 NM_001136015 5'UTR N_Shore . 2.04E-05 0.000560282 3.808196653 0.056572464 0.215719887 Hyper cg26147845 chr12 132433837 132433838 EP400 NM_015409 TSS1500N_Shore Promoter 3.92E-06 0.000301217 3.643351981 0.077868629 0.283967159 Hyper cg23737061 chr3 60226327 60226328 FHIT NM_001166243 Body . 1.65E-07 0.000239667 3.616168212 0.093920309 0.339893251 Hyper cg18215449 chr12 66089472 66089473 . 4.22E-07 0.000239667 3.565225234 0.064067475 0.228671502 Hyper cg24082121 chr5 672871 672872 TPPP NM_007030 Body . 1.78E-05 0.000525064 3.505843071 0.089095718 0.312606189 Hyper cg23032421 chr3 3152037 3152038 IL5RA NM_175727 5'UTR . 1.04E-05 0.00041338 3.371418731 0.114213604 0.385299026 Hyper cg11737172 chr8 1923051 1923052 KBTBD11 NM_014867 5'UTR S_Shore . 1.38E-05 0.000466865 3.368483202 0.108495063 0.365700645 Hyper cg16886175 chr7 114562062 114562063 MDFIC NM_001166345 TSS200 N_Shore Promoter 7.28E-07 0.000243374 3.35638256 0.101463003 0.340784291 Hyper cg10986412 chr5 672909 672910 TPPP NM_007030 Body . 1.56E-06 0.000255546 3.316242102 0.071981379 0.238939304 Hyper cg02025737 chr15 33384750 33384751 . 3.80E-05 0.000776402 3.312390381 0.13643852 0.452168879 Hyper cg06243675 chr8 11801364 11801365 . 5.23E-05 0.000932639 3.254014485 0.016251643 0.053108482 Hyper cg09577804 chr10 3235531 3235532 . 5.04E-05 0.000912242 3.247042327 0.043496295 0.141459016 Hyper cg23057220 chr19 1356314 1356315 MUM1 NR_024247 TSS200 S_Shore Promoter 3.65E-05 0.000758178 3.204370027 0.14549078 0.466426732 Hyper cg06984883 chr1 1243563 1243564 PUSL1 NM_153339 TSS1500Island Promoter 5.07E-06 0.000323878 3.198831858 0.005047892 0.01636724 Hyper cg15963463 chr1 25253236 25253237 RUNX3 NM_001031680 Body N_Shelf . -

1 SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Oligonucleotide Array-QC-Labeling

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Oligonucleotide Array-QC-Labeling and sample processing. High density oligonucleotide Affymetrix U133A chips, representing approximately 22,000 genes and 1,000 ESTs, were used in this study according to manufacturer’s protocols. U133A microarray data from human OEAs will be published elsewhere (Cho laboratory, manuscript in preparation). RNA quality control was performed prior to labeling: 25 to 50 nanograms of total RNA was run on a RNA 6000 Nano Assay (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) using a Bioanlyzer 2100. 2 µg of total RNA was then labeled according to protocols recommended by manufacturers. Briefly, after reverse transcription with an oligo-(dT)24- T7 (Genset), double stranded cDNA was generated with the Superscript double stranded cDNA synthesis custom kit (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). In an in vitro transcription step (IVT) with T7 RNA polymerase (MessageAmp aRNA kit from Ambion, Austin, TX), the cDNA was linearly amplified and labeled with biotinylated nucleotides (Enzo Diagnostics, Farmingdale, NY). 10 ug of labeled and fragmented cRNA was then hybridized onto a human genome U133A expression array (Affymetrix) for 16 hours at 450C. Post-hybridization fluorescent staining was processed according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Affymetrix). Finally, chips were scanned with a Hewlett Packard argon-ion laser confocal scanner. The image was quantified using Microarray Suite 5.1 (MAS 5.1, Affymetrix) with the default parameters for the statistical algorithm. RT-PCR. Total RNA from cells was isolated using Qiagen RNAeasy Kits according to manufacturer instructions. Total RNA from frozen tissues was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed using Superscript One-Step RT-PCR (Invitrogen). -

A Novel Thermostable Aspartic Protease from Talaromyces Leycettanus and Its Specific

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/528265; this version posted January 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 1 RESEARCH ARTICLE 2 3 A novel thermostable aspartic protease from Talaromyces leycettanus and its specific 4 autocatalytic activation through an intermediate transition state 5 6 Yujie Guo1, Tao Tu1, Yaxin Ren1, Yaru Wang1, Yingguo Bai1, Xiaoyun Su1, Yuan 7 Wang1, Bin Yao1, Huoqing Huang1*, Huiying Luo1* 8 9 1Key Laboratory for Feed Biotechnology of the Ministry of Agriculture, Feed Research 10 Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing 100081, P. R. China 11 Running title: Insights into a specific auto-activation of proTlAPA1 12 * Corresponding authors. 13 E-mail addresses: [email protected] (H. Luo), [email protected] (H. Huang). 2 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/528265; this version posted January 23, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 14 ABSTRACT 15 Aspartic proteases exhibit optimum enzyme activity under acidic condition and 16 have been extensively used in food, fermentation and leather industries. In this study, 17 a novel aspartic protease precursor (proTlAPA1) from Talaromyces leycettanus was 18 identified and successfully expressed in Pichia pastoris. Subsequently, the 19 auto-activation processing of the zymogen proTlAPA1 was studied by SDS-PAGE 20 and N-terminal sequencing, under different processing conditions. TlAPA1 shared the 21 highest identity of 70.3 % with the aspartic endopeptidase from Byssochlamys 22 spectabilis (GAD91729) and was classified into a new subgroup of the aspartic 23 protease A1 family, based on evolutionary analysis. -

The Cysteine Protease–Cysteine Protease Inhibitor System Explored in Soybean Nodule Development

Agronomy 2013, 3, 550-570; doi:10.3390/agronomy3030550 OPEN ACCESS agronomy ISSN 2073-4395 www.mdpi.com/journal/agronomy Discussion The Cysteine Protease–Cysteine Protease Inhibitor System Explored in Soybean Nodule Development Barend Juan Vorster 1,†, Urte Schlüter 2,†, Magdeleen du Plessis 1, Stefan van Wyk 1, Matome Eugene Makgopa 2, Ignatious Ncube 3, Marian Dorcas Quain 4, Karl Kunert 2 and Christine Helen Foyer 4,* 1 Department of Plant Production and Soil Science, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa; E-Mails: [email protected] (B.J.V.); [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (S.W.) 2 Department of Plant Science, Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0002, South Africa; E-Mails: [email protected] (U.S.); [email protected] (M.E.M.); [email protected] (K.K.) 3 Biotechnology Unit School of Molecular and Life Sciences, University of Limpopo, Sovenga 0727, South Africa; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Center for Plant Sciences, Faculty of Biology, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-113-343-1421; Fax: +44-113-343-2882. Received: 29 May 2013; in revised form: 12 July 2013 / Accepted: 22 July 2013 / Published: 20 August 2013 Abstract: Almost all protease families have been associated with plant development, particularly senescence, which is the final developmental stage of every organ before cell death.