Chapter2 Layout 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Contrasting Phanerozoic Orogenic Systems Revealed by Hafnium Isotope Data William J

ARTICLES PUBLISHED ONLINE: 17 APRIL 2011 | DOI: 10.1038/NGEO1127 Two contrasting Phanerozoic orogenic systems revealed by hafnium isotope data William J. Collins1*(, Elena A. Belousova2, Anthony I. S. Kemp1 and J. Brendan Murphy3 Two fundamentally different orogenic systems have existed on Earth throughout the Phanerozoic. Circum-Pacific accretionary orogens are the external orogenic system formed around the Pacific rim, where oceanic lithosphere semicontinuously subducts beneath continental lithosphere. In contrast, the internal orogenic system is found in Europe and Asia as the collage of collisional mountain belts, formed during the collision between continental crustal fragments. External orogenic systems form at the boundary of large underlying mantle convection cells, whereas internal orogens form within one supercell. Here we present a compilation of hafnium isotope data from zircon minerals collected from orogens worldwide. We find that the range of hafnium isotope signatures for the external orogenic system narrows and trends towards more radiogenic compositions since 550 Myr ago. By contrast, the range of signatures from the internal orogenic system broadens since 550 Myr ago. We suggest that for the external system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle beneath the overriding continent is removed during subduction and replaced by newly formed crust, which generates the radiogenic hafnium signature when remelted. For the internal orogenic system, the lower crust and lithospheric mantle is instead eventually replaced by more continental lithosphere from a collided continental fragment. Our suggested model provides a simple basis for unravelling the global geodynamic evolution of the ancient Earth. resent-day orogens of contrasting character can be reduced to which probably began by the Early Ordovician12, and the Early two types on Earth, dominantly accretionary or dominantly Paleozoic accretionary orogens in the easternmost Altaids of Pcollisional, because only the latter are associated with Wilson Asia13. -

The North-Subducting Rheic Ocean During the Devonian: Consequences for the Rhenohercynian Ore Sites

Published in "International Journal of Earth Sciences 106(7): 2279–2296, 2017" which should be cited to refer to this work. The north-subducting Rheic Ocean during the Devonian: consequences for the Rhenohercynian ore sites Jürgen F. von Raumer1 · Heinz-Dieter Nesbor2 · Gérard M. Stampfli3 Abstract Base metal mining in the Rhenohercynian Zone activated Early Devonian growth faults. Hydrothermal brines has a long history. Middle-Upper Devonian to Lower Car- equilibrated with the basement and overlying Middle-Upper boniferous sediment-hosted massive sulfide deposits Devonian detrital deposits forming the SHMS deposits in the (SHMS), volcanic-hosted massive sulfide deposits (VHMS) southern part of the Pyrite Belt, in the Rhenish Massif and and Lahn-Dill-type iron, and base metal ores occur at sev- in the Harz areas. Volcanic-hosted massive sulfide deposits eral sites in the Rhenohercynian Zone that stretches from the (VHMS) formed in the more eastern localities of the Rheno- South Portuguese Zone, through the Lizard area, the Rhen- hercynian domain. In contrast, since the Tournaisian period ish Massif and the Harz Mountain to the Moravo-Silesian of ore formation, dominant pull-apart triggered magmatic Zone of SW Bohemia. During Devonian to Early Carbonif- emplacement of acidic rocks, and their metasomatic replace- erous times, the Rhenohercynian Zone is seen as an evolv- ment in the apical zones of felsic domes and sediments in ing rift system developed on subsiding shelf areas of the the northern part of the Iberian Pyrite belt, thus changing the Old Red continent. A reappraisal of the geotectonic setting general conditions of ore precipitation. -

Neoproterozoic Glaciations in a Revised Global Palaeogeography from the Breakup of Rodinia to the Assembly of Gondwanaland

Sedimentary Geology 294 (2013) 219–232 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Sedimentary Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sedgeo Invited review Neoproterozoic glaciations in a revised global palaeogeography from the breakup of Rodinia to the assembly of Gondwanaland Zheng-Xiang Li a,b,⁎, David A.D. Evans b, Galen P. Halverson c,d a ARC Centre of Excellence for Core to Crust Fluid Systems (CCFS) and The Institute for Geoscience Research (TIGeR), Department of Applied Geology, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth, WA 6845, Australia b Department of Geology and Geophysics, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06520-8109, USA c Earth & Planetary Sciences/GEOTOP, McGill University, 3450 University St., Montreal, Quebec H3A0E8, Canada d Tectonics, Resources and Exploration (TRaX), School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, SA 5005, Australia article info abstract Article history: This review paper presents a set of revised global palaeogeographic maps for the 825–540 Ma interval using Received 6 January 2013 the latest palaeomagnetic data, along with lithological information for Neoproterozoic sedimentary basins. Received in revised form 24 May 2013 These maps form the basis for an examination of the relationships between known glacial deposits, Accepted 28 May 2013 palaeolatitude, positions of continental rifting, relative sea-level changes, and major global tectonic events Available online 5 June 2013 such as supercontinent assembly, breakup and superplume events. This analysis reveals several fundamental ’ Editor: J. Knight palaeogeographic features that will help inform and constrain models for Earth s climatic and geodynamic evolution during the Neoproterozoic. First, glacial deposits at or near sea level appear to extend from high Keywords: latitudes into the deep tropics for all three Neoproterozoic ice ages (Sturtian, Marinoan and Gaskiers), al- Neoproterozoic though the Gaskiers interval remains very poorly constrained in both palaeomagnetic data and global Rodinia lithostratigraphic correlations. -

Detrital Zircon Provenance and Lithofacies Associations Of

geosciences Article Detrital Zircon Provenance and Lithofacies Associations of Montmorillonitic Sands in the Maastrichtian Ripley Formation: Implications for Mississippi Embayment Paleodrainage Patterns and Paleogeography Jennifer N. Gifford 1,*, Elizabeth J. Vitale 1, Brian F. Platt 1 , David H. Malone 2 and Inoka H. Widanagamage 1 1 Department of Geology and Geological Engineering, University of Mississippi, Oxford, MS 38677, USA; [email protected] (E.J.V.); [email protected] (B.F.P.); [email protected] (I.H.W.) 2 Department of Geography, Geology, and the Environment, Illinois State University, Normal, IL 61790, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: jngiff[email protected]; Tel.: +1-(662)-915-2079 Received: 17 January 2020; Accepted: 15 February 2020; Published: 22 February 2020 Abstract: We provide new detrital zircon evidence to support a Maastrichtian age for the establishment of the present-day Mississippi River drainage system. Fieldwork conducted in Pontotoc County,Mississippi, targeted two sites containing montmorillonitic sand in the Maastrichtian Ripley Formation. U-Pb detrital zircon (DZ) ages from these sands (n = 649) ranged from Mesoarchean (~2870 Ma) to Pennsylvanian (~305 Ma) and contained ~91% Appalachian-derived grains, including Appalachian–Ouachita, Gondwanan Terranes, and Grenville source terranes. Other minor source regions include the Mid-Continent Granite–Rhyolite Province, Yavapai–Mazatzal, Trans-Hudson/Penokean, and Superior. This indicates that sediment sourced from the Appalachian Foreland Basin (with very minor input from a northern or northwestern source) was being routed through the Mississippi Embayment (MSE) in the Maastrichtian. We recognize six lithofacies in the field areas interpreted as barrier island to shelf environments. Statistically significant differences between DZ populations and clay mineralogy from both sites indicate that two distinct fluvial systems emptied into a shared back-barrier setting, which experienced volcanic ash input. -

Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA)

Industry Update from Canada: Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA) Monday, 6 July 2020 In partnership with Welcome Michael Barton Regional Director, Canada Invest Northern Ireland – Americas For up to date information on Invest Northern Ireland in the Americas, follow us on LinkedIn & Twitter. Invest Northern Ireland – Americas @InvestNI_USA 2 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Industry Updates Sessions with industry experts to provide Northern Ireland manufacturers with updates on the Americas markets to assist with export planning and preparation Today’s Update We are delighted to welcome Beverly Leavitt, President & CEO of the Canada East Equipment Dealers' Association (CEEDA). CEEDA represents Equipment Dealers in the Province of Ontario, and the Atlantic Provinces in the Canadian Maritimes. 3 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian Agri-tech sector… Virtual Meet-the-Buyer programs designed to provide 1:1 support to connect Northern Ireland manufacturers with potential Canadian equipment dealers Ongoing dealer development in Eastern & Western Canada For new-to-market exporters, provide support, industry information and routes to market For existing exporters, market expansion and exploration of new Provinces 4 Invest Northern Ireland – Americas: Export Continuity Support in the Face of COVID-19 Industry Interruption For the Canadian -

129 the Use of Joint Patterns for Understanding The

129 THE USE OF JOINT PATTERNS FOR UNDERSTANDING THE ALLEGHANIAN OROGENY IN THE UPPER DEVONIAN APPALACHIAN BASIN, FINGER LAKES DISTRICT, NEW YORK TERRY ENGELDER Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania 16802 REGIONAL SIGNIFICANCE Abundantevidence (deformed fo ssils) for layer parallel shortening in western New York indicates the extent to which the Alleghanian Orogeny affected the Appalachian Plateau (Engelder and Engelder, 1977). In addition to low amplitude ( 100 m) long wave length ( 15 km) folds the Upper Devonian sediments of western New York contain many< mesoscopic-scale structures< including joints that can be systematically related to the Alleghanian Orogeny. Based on the nonorthogonality of cleavage and joints, the Alleghanian Orogeny in the Finger Lakes District of New York consists of at least two phases which Geiser and Engelder (1983) correlate with folding and cross-cutting cleavages in the Appalachian Valley and Ridge. To the southeast of the Finger Lakes District the earlier Lackawanna Phase is manifested by formation of the Lackawanna syncline and Green Pond outlier and the development of a northeast-striking disjunctive cleavage within the Appalachian Valley and Ridge mainly fromthe Kingston Arch of the Hudson Valley southwestward beyond Port Jervis, Pennsylvania (Fig. 1). Within the Finger Lakes Distric� New York, a Lackawanna Phase cleavage is absent; and one fm ds instead a cross-fold joint set which is consistent in orientation with a Lackawanna Phase compression. In bedded siltstone-shale sequences (i.e. the Genesee Group) this cross-fold joint set favors development in the siltstones 1# 2#). Main Phase (stops and The is seen as the refolding of the Lackawanna syncline and Green Pond outlier, as well as the development of the major folds in central Pennsylvania. -

Atlantic Agriculture

FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF DALHOUSIE’S FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE SPRING 2021 Atlantic agriculture In memory Passing of Jim Goit In June 2020, campus was saddened with the sudden passing The Agricultural Campus and the Alumni Association of Jim Goit, former executive director, Development & External acknowledge the passing of the following alumni. We extend Relations. Jim had a long and lustrous 35-year career with the our deepest sympathy to family, friends and classmates. Province of NS, 11 of which were spent at NSAC (and the Leonard D’Eon 1940 Faculty of Agriculture). Jim’s impact on campus was Arnold Blenkhorn 1941 monumental – he developed NSAC’s first website, created Clara Galway 1944 an alumni and fundraising program and built and maintained Thomas MacNaughton 1946 many critical relationships. For his significant contributions, George Leonard 1947 Jim was awarded an honourary Barley Ring in 2012. Gerald Friars 1948 James Borden 1950 Jim retired in February 2012 and was truly living his best life. Harry Stewart 1951 On top of enjoying the extra time with his wife, Barb, their sons Stephen Cook 1954 and four grandchildren, he became highly involved in the Truro Gerald Foote 1956 Rotary Club and taught ski lessons in the winter. In retirement, Albert Smith 1957 Jim also enjoyed cooking, travelling, yard work and cycling. George Mauger 1960 Phillip Harrison 1960 In honour of Jim’s contributions to campus and the Alumni Barbara Martin 1962 Association, a bench was installed in front of Cumming Peter Dekker 1964 Hall in late November. Wayne Bhola Neil Murphy 1964 (Class of ’74) kindly constructed the Weldon Smith 1973 beautiful bench in Jim’s memory. -

Canada GREENLAND 80°W

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-B Module 7 70°N 30°W 20°W 170°W 180° 70°N 160°W Canada GREENLAND 80°W 90°W 150°W 100°W (DENMARK) 120°W 140°W 110°W 60°W 130°W 70°W ARCTIC Essential Question OCEANDo Canada’s many regional differences strengthen or weaken the country? Alaska Baffin 160°W (UNITED STATES) Bay ic ct r le Y A c ir u C k o National capital n M R a 60°N Provincial capital . c k e Other cities n 150°W z 0 200 400 Miles i Iqaluit 60°N e 50°N R YUKON . 0 200 400 Kilometers Labrador Projection: Lambert Azimuthal TERRITORY NUNAVUT Equal-Area NORTHWEST Sea Whitehorse TERRITORIES Yellowknife NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Hudson N A Bay ATLANTIC 140°W W E St. John’s OCEAN 40°W BRITISH H C 40°N COLUMBIA T QUEBEC HMH Middle School World Geography A MANITOBA 50°N ALBERTA K MS_SNLESE668737_059M_K.ai . S PRINCE EDWARD ISLAND R Edmonton A r Canada legend n N e a S chew E s kat Lake a as . Charlottetown r S R Winnipeg F Color Alts Vancouver Calgary ONTARIO Fredericton W S Island NOVA SCOTIA 50°WFirst proof: 3/20/17 Regina Halifax Vancouver Quebec . R 2nd proof: 4/6/17 e c Final: 4/12/17 Victoria Winnipeg Montreal n 130°W e NEW BRUNSWICK Lake r w Huron a Ottawa L PACIFIC . t S OCEAN Lake 60°W Superior Toronto Lake Lake Ontario UNITED STATES Lake Michigan Windsor 100°W Erie 90°W 40°N 80°W 70°W 120°W 110°W In this module, you will learn about Canada, our neighbor to the north, Explore ONLINE! including its history, diverse culture, and natural beauty and resources. -

The Geology of England – Critical Examples of Earth History – an Overview

The Geology of England – critical examples of Earth history – an overview Mark A. Woods*, Jonathan R. Lee British Geological Survey, Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG *Corresponding Author: Mark A. Woods, email: [email protected] Abstract Over the past one billion years, England has experienced a remarkable geological journey. At times it has formed part of ancient volcanic island arcs, mountain ranges and arid deserts; lain beneath deep oceans, shallow tropical seas, extensive coal swamps and vast ice sheets; been inhabited by the earliest complex life forms, dinosaurs, and finally, witnessed the evolution of humans to a level where they now utilise and change the natural environment to meet their societal and economic needs. Evidence of this journey is recorded in the landscape and the rocks and sediments beneath our feet, and this article provides an overview of these events and the themed contributions to this Special Issue of Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, which focuses on ‘The Geology of England – critical examples of Earth History’. Rather than being a stratigraphic account of English geology, this paper and the Special Issue attempts to place the Geology of England within the broader context of key ‘shifts’ and ‘tipping points’ that have occurred during Earth History. 1. Introduction England, together with the wider British Isles, is blessed with huge diversity of geology, reflected by the variety of natural landscapes and abundant geological resources that have underpinned economic growth during and since the Industrial Revolution. Industrialisation provided a practical impetus for better understanding the nature and pattern of the geological record, reflected by the publication in 1815 of the first geological map of Britain by William Smith (Winchester, 2001), and in 1835 by the founding of a national geological survey. -

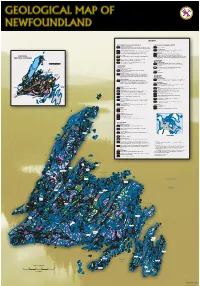

Geology Map of Newfoundland

LEGEND POST-ORDOVICIAN OVERLAP SEQUENCES POST-ORDOVICIAN INTRUSIVE ROCKS Carboniferous (Viséan to Westphalian) Mesozoic Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and minor carbonate rocks; intercalated marine, Gabbro and diabase siliciclastic, carbonate and evaporitic rocks; minor coal beds and mafic volcanic flows Devonian and Carboniferous Devonian and Carboniferous (Tournaisian) Granite and high silica granite (sensu stricto), and other granitoid intrusions Fluviatile and lacustrine sandstone, shale, conglomerate and minor carbonate rocks that are posttectonic relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies Fluviatile and lacustrine, siliciclastic and carbonate rocks; subaerial, bimodal Silurian and Devonian volcanic rocks; may include some Late Silurian rocks Gabbro and diorite intrusions, including minor ultramafic phases Silurian and Devonian Posttectonic gabbro-syenite-granite-peralkaline granite suites and minor PRINCIPAL Shallow marine sandstone, conglomerate, limey shale and thin-bedded limestone unseparated volcanic rocks (northwest of Red Indian Line); granitoid suites, varying from pretectonic to syntectonic, relative to mid-Paleozoic orogenies (southeast of TECTONIC DIVISIONS Silurian Red Indian Line) TACONIAN Bimodal to mainly felsic subaerial volcanic rocks; includes unseparated ALLOCHTHON sedimentary rocks of mainly fluviatile and lacustrine facies GANDER ZONE Stratified rocks Shallow marine and non-marine siliciclastic sedimentary rocks, including Cambrian(?) and Ordovician 0 150 sandstone, shale and conglomerate Quartzite, psammite, -

Atlantic Canada Guidelines for Drinking Water Supply Systems

Water SupplySystems Storage, Distribution Atlant i c Canada Guidelines , andOperationof Atlantic Canada Guidelines for the Supply, for Treatment, Storage, t h Distribution, and e Supply, Operation of Drinking Water Supply Systems Dr i Treatment, n king September 2004 Prepared by: Coordinated by the Atlantic Canada Water Works Association (ACWWA) in association with the four Atlantic Canada Provinces WATER SYSTEM DESIGN GUIDELINE MANUAL PURPOSE AND USE OF MANUAL Page 1 PURPOSE AND USE OF MANUAL Purpose The purpose of the Atlantic Canada Guidelines for the Supply, Treatment, Storage, Distribution and Operation of Drinking Water Supply Systems is to provide a guide for the development of water supply projects in Atlantic Canada. The document is intended to serve as a guide in the evaluation of water supplies, and for the design and preparation of plans and specifications for projects. The document will suggest limiting values for items upon which an evaluation of such plans and specifications may be made by the regulator, and will establish, as far is practical, uniformity of practice. The document should be considered to be a companion to the Atlantic Canada Standards and Guidelines Manual for the Collection, Treatment and Disposal of Sanitary Sewage. Limitations Users of the Manual are advised that requirements for specific issues such as filtration, equipment redundancy, and disinfection are not uniform among the Atlantic Canada provinces, and that the appropriate regulator should be contacted prior to, or during, an investigation to discuss specific key requirements. Approval Process Chapter 1 of the Manual provides an overview of the approval process generally used by the regulators. -

Intrusive and Depositional Constraints on the Cretaceous Tectonic History of the Southern Blue Mountains, Eastern Oregon

THEMED ISSUE: EarthScope IDOR project (Deformation and Magmatic Modification of a Steep Continental Margin, Western Idaho–Eastern Oregon) Intrusive and depositional constraints on the Cretaceous tectonic history of the southern Blue Mountains, eastern Oregon R.M. Gaschnig1,*, A.S. Macho2,*, A. Fayon3, M. Schmitz4, B.D. Ware4,*, J.D. Vervoort5, P. Kelso6, T.A. LaMaskin7, M.J. Kahn2, and B. Tikoff2 1SCHOOL OF EARTH AND ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES, GEORGIA INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, 311 FERST DRIVE, ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30332, USA 2DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCE, UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON, 1215 W DAYTON STREET, MADISON, WISCONSIN 53706, USA 3DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES, UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA TWIN CITIES, 310 PILLSBURY DRIVE SE, MINNEAPOLIS, MINNESOTA 55455, USA 4DEPARTMENT OF GEOSCIENCES, BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY, 1910 UNIVERSITY DRIVE, BOISE, IDAHO 83725, USA 5SCHOOL OF THE ENVIRONMENT, WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY, PO BOX 64281, PULLMAN, WASHINGTON 99164, USA 6DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND PHYSICS, LAKE SUPERIOR STATE UNIVERSITY, CRAWFORD HALL OF SCIENCE, SAULT STE. MARIE, MICHIGAN 49783, USA 7DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, DELOACH HALL, 601 SOUTH COLLEGE ROAD, WILMINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA 28403, USA ABSTRACT We present an integrated study of the postcollisional (post–Late Jurassic) history of the Blue Mountains province (Oregon and Idaho, USA) using constraints from Cretaceous igneous and sedimentary rocks. The Blue Mountains province consists of the Wallowa and Olds Ferry arcs, separated by forearc accretionary material of the Baker terrane. Four plutons (Lookout Mountain, Pedro Mountain, Amelia, Tureman Ranch) intrude along or near the Connor Creek fault, which separates the Izee and Baker terranes. High-precision U-Pb zircon ages indicate 129.4–123.8 Ma crystallization ages and exhibit a north-northeast–younging trend of the magmatism.