Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 26 January to December 2016 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND Index 2016_4.indd 1 14/12/2016 17:41 SUBJECT INDEX SUBJECT INDEX After the Storm (2016) 7:25 (magazine) 9:102 7:43; 10:47; 11:41 Orlando 6:112 effect on technological Film review titles are also Agace, Mel 1:15 American Film Institute (AFI) 3:53 Apologies 2:54 Ran 4:7; 6:94-5; 9:111 changes 8:38-43 included and are indicated by age and cinema American Friend, The 8:12 Appropriate Behaviour 1:55 Jacques Rivette 3:38, 39; 4:5, failure to cater for and represent (r) after the reference; growth in older viewers and American Gangster 11:31, 32 Aquarius (2016) 6:7; 7:18, Céline and Julie Go Boating diversity of in 2015 1:55 (b) after reference indicates their preferences 1:16 American Gigolo 4:104 20, 23; 10:13 1:103; 4:8, 56, 57; 5:52, missing older viewers, growth of and A a book review Agostini, Philippe 11:49 American Graffiti 7:53; 11:39 Arabian Nights triptych (2015) films of 1970s 3:94-5, Paris their preferences 1:16 Aguilar, Claire 2:16; 7:7 American Honey 6:7; 7:5, 18; 1:46, 49, 53, 54, 57; 3:5: nous appartient 4:56-7 viewing films in isolation, A Aguirre, Wrath of God 3:9 10:13, 23; 11:66(r) 5:70(r), 71(r); 6:58(r) Eric Rohmer 3:38, 39, 40, pleasure of 4:12; 6:111 Aaaaaaaah! 1:49, 53, 111 Agutter, Jenny 3:7 background -

The Rite of Sodomy

The Rite of Sodomy volume iii i Books by Randy Engel Sex Education—The Final Plague The McHugh Chronicles— Who Betrayed the Prolife Movement? ii The Rite of Sodomy Homosexuality and the Roman Catholic Church volume iii AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution Randy Engel NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Export, Pennsylvania iii Copyright © 2012 by Randy Engel All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, New Engel Publishing, Box 356, Export, PA 15632 Library of Congress Control Number 2010916845 Includes complete index ISBN 978-0-9778601-7-3 NEW ENGEL PUBLISHING Box 356 Export, PA 15632 www.newengelpublishing.com iv Dedication To Monsignor Charles T. Moss 1930–2006 Beloved Pastor of St. Roch’s Parish Forever Our Lady’s Champion v vi INTRODUCTION Contents AmChurch and the Homosexual Revolution ............................................. 507 X AmChurch—Posing a Historic Framework .................... 509 1 Bishop Carroll and the Roots of the American Church .... 509 2 The Rise of Traditionalism ................................. 516 3 The Americanist Revolution Quietly Simmers ............ 519 4 Americanism in the Age of Gibbons ........................ 525 5 Pope Leo XIII—The Iron Fist in the Velvet Glove ......... 529 6 Pope Saint Pius X Attacks Modernism ..................... 534 7 Modernism Not Dead— Just Resting ...................... 538 XI The Bishops’ Bureaucracy and the Homosexual Revolution ... 549 1 National Catholic War Council—A Crack in the Dam ...... 549 2 Transition From Warfare to Welfare ........................ 551 3 Vatican II and the Shaping of AmChurch ................ 561 4 The Politics of the New Progressivism .................... 563 5 The Homosexual Colonization of the NCCB/USCC ....... -

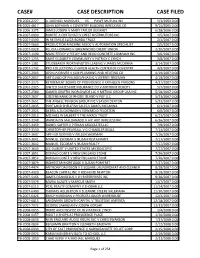

Case# Case Description Case Filed

CASE# CASE DESCRIPTION CASE FILED PB-2003-2227 A. MICHAEL MARQUES VS PAWT MUTUAL INS 5/1/2003 0:00 PB-2005-4817 JOHN BOYAJIAN V COVENTRY BUILDING WRECKING CO 9/15/2005 0:00 PB-2006-3375 JAMES JOSEPH V MARY TAYLOR DEVANEY 6/28/2006 0:00 PB-2007-0090 ROBERT A FORTUNATI V CREST DISTRIBUTORS INC 1/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0590 IN RE EMILIE LUIZA BORDA TRUST 2/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0663 PRODUCTION MACHINE ASSOC V AUTOMATION SPECIALIST 2/5/2007 0:00 PB-2007-0928 FELICIA HOWARD V GREENWOOD CREDIT UNION 2/20/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1190 MARC FEELEY V FEELEY AND REGO CONCRETE COMPANY INC 3/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1255 SAINT ELIZABETH COMMUNITY V PATRICK C LYNCH 3/8/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1381 STUDEBAKER WORTHINGTON LEASING V JAMES MCCANNA 3/14/2007 0:00 PB-2007-1742 PRO COLLECTIONS V HAVEN HEALTH CENTER OF COVENTRY 4/9/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2043 JOSHUA DRIVER V KLM PLUMBING AND HEATING CO 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2057 ART GUILD OF PHILADELPHIA INC V JEFFREY FREEMAN 4/19/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2175 RETIREMENT BOARD OF PROVIDENCE V KATHLEEN PARSONS 4/27/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2325 UNITED STATES FIRE INSURANCE CO V ANTHONY ROSCITI 5/7/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2580 GAMER GRAFFIX WORLDWIDE LLC V METINO GROUP USA INC 5/18/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2637 CITIZENS BANK OF RHODE ISLAND V PGF LLC 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2651 THE ANGELL PENSION GROUP INC V JASON DENTON 5/23/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2835 PORTLAND SHELLFISH SALES V JAMES MCCANNA 6/1/2007 0:00 PB-2007-2925 DEBRA A ZUCKERMAN V EDWARD D FELDSTEIN 6/6/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3015 MICHAEL W JALBERT V THE MKRCK TRUST 6/13/2007 0:00 PB-2007-3248 WANDALYN MALDANADO -

Suicide of Holly Glynn from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Suicide of Holly Glynn From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Holly Glynn High school portrait of Holly Glynn, circa 1984 Born Holly Jo Glynn September 11, 1966 Died September 20, 1987 (aged 21) Dana Point, Orange County, California Cause of death Suicide by jumping Other names Dana Point Jane Doe Known for Former unidentified decedent Holly Jo Glynn (September 11, 1966 – September 20, 1987)[1] was a formerly unidentified American woman who is believed to have committed suicide in September 1987 by jumping off a cliff in Dana Point, California. Her body remained unidentified until 2015,[2][3] when concerns previously expressed by friends of Glynn that the unidentified woman may have been their childhood friend, whom they had been unable to locate for several years, were proven to be true.[4] Prior to her May 2015 identification, Glynn's body had been informally known as the Dana Point Jane Doe, and officially as Jane Doe 87-04457-EL[2] Contents [hide] • 1Discovery o 1.1Distinguishing characteristics • 2Eyewitness accounts o 2.1Further investigation • 3Identification • 4See also • 5Notes • 6References • 7External links Discovery[edit] At 6:40 on the morning of September 20, 1987, the body of a young Caucasian woman was discovered by joggers at the base of a cliff at Dana Point, California. Her body had no form of identification on her possession, although at the top of the cliff, investigators discovered a half consumed can of Coca-Cola, a purse containing small change, a packet of cigarettes, matches, and two maps of Southern California. On the rear of one of these maps was written the telephone number of a local taxi firm in addition to other notations she had written, indicating she may have asked several individuals for directions. -

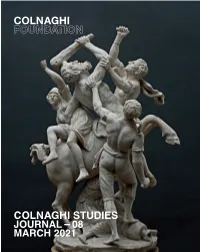

Journal 08 March 2021 Editorial Committee

JOURNAL 08 MARCH 2021 EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Stijn Alsteens International Head of Old Master Drawings, Patrick Lenaghan Curator of Prints and Photographs, The Hispanic Society of America, Christie’s. New York. Jaynie Anderson Professor Emeritus in Art History, The Patrice Marandel Former Chief Curator/Department Head of European Painting and JOURNAL 08 University of Melbourne. Sculpture, Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Charles Avery Art Historian specializing in European Jennifer Montagu Art Historian specializing in Italian Baroque. Sculpture, particularly Italian, French and English. Scott Nethersole Senior Lecturer in Italian Renaissance Art, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London. Andrea Bacchi Director, Federico Zeri Foundation, Bologna. Larry Nichols William Hutton Senior Curator, European and American Painting and Colnaghi Studies Journal is produced biannually by the Colnaghi Foundation. Its purpose is to publish texts on significant Colin Bailey Director, Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Sculpture before 1900, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio. pre-twentieth-century artworks in the European tradition that have recently come to light or about which new research is Piers Baker-Bates Visiting Honorary Associate in Art History, Tom Nickson Senior Lecturer in Medieval Art and Architecture, Courtauld Institute of Art, underway, as well as on the history of their collection. Texts about artworks should place them within the broader context The Open University. London. of the artist’s oeuvre, provide visual analysis and comparative images. Francesca Baldassari Professor, Università degli Studi di Padova. Gianni Papi Art Historian specializing in Caravaggio. Bonaventura Bassegoda Catedràtic, Universitat Autònoma de Edward Payne Assistant Professor in Art History, Aarhus University. Manuscripts may be sent at any time and will be reviewed by members of the journal’s Editorial Committee, composed of Barcelona. -

School Excursions

FOLD LINES – DO NOT PRINT FRONT COVER 2017 STAGES 4, 5 & 6 SYDNEY LIVING MUSEUMS SCHOOL EXCURSIONS BOOK NOW FOR 2017 11 PROGRAMS • 5 SITES • NEW VIRTUAL EXCURSION INSIDE FRONT COVER 2017 STAGES 4, 5 & 6 SCHOOL EXCURSIONS CONTENTS WELCOME STAGE 4 Take a journey through time with Sydney Hyde Park Barracks Museum 4 Living Museums to interpret the past. With Sydney Living Museums your students will Museum of Sydney 6 discover past lives, events and stories in STAGE 5 the places where they actually unfolded. Hyde Park Barracks Museum 8 Our History programs ensure that students are STAGES 5 & 6 active participants in historical investigation, Justice & Police Museum 10 involving students in the analysis of primary and STAGE 6 secondary sources and the use of evidence to develop informed responses to inquiry questions. Susannah Place Museum 12 The Project 13 Our programs for secondary school students cover a range of topics, outcomes and cross- PARTNER PROGRAMS curriculum priorities from the NSW Syllabus for Museums Discovery Centre 14 the Australian Curriculum: History K-10. Muru Mittigar inside back cover Led by our highly trained staff, more than 10,000 high BOOKINGS 15 school students participate in our programs every year across our unique museums and historic houses. We look forward to welcoming you and your students in 2017. Mark Goggin Executive Director Students at Susannah Place Museum during Archaeology in The Rocks, learning about the Cunninghame family, who once lived at 60 Gloucester Street. Photo © James Horan for Sydney Living Museums HYDE PARK BARRACKS MUSEUM SYDNEY The rich history and collections of this UNESCO World Heritage-listed site provide your students with unparalleled opportunities to investigate primary sources, including archaeological material. -

Hartford Circus Fire

Hartford circus fire Hartford circus fire Tent on fire Date July 6, 1944 Location Hartford, Connecticut The Hartford circus fire, which occurred on July 6, 1944, in Hartford, Connecticut, was one of the worst fire disasters in the history of the United States.The fire occurred during an afternoon performance of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus that was attended by 6,000 to 8,000 people. The fire killed 167 people and more than 700 were injured. Background In mid-20th century America, a typical circus traveled from town to town by train, performing under a huge canvas tent commonly called a "big top". The Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus was no exception: what made it stand out was that it was the largest circus in the country. Its big top could seat 9,000 spectators around its three rings; the tent's canvas had been coated with 1,800 pounds (820 kg) of paraffin wax dissolved in 6,000 US gallons (23,000 l) of gasoline, a common waterproofing method of the time.[ The circus had been experiencing shortages of personnel and equipment as a result of the United States' involvement in World War II. Delays and malfunctions in the ordinarily smooth order of the circus had become commonplace; on August 4, 1942, a fire had broken out in the menagerie, killing a number of animals. When the circus arrived in Hartford, Connecticut, on July 5, 1944, the trains were so late that one of the two shows scheduled for that day had been canceled. In circus superstition, missing a show is considered extremely bad luck, and although the July 5, 1944 evening show ran as planned, many circus employees may have been on their guard, half-expecting an emergency or catastrophe. -

A Brief History of Forensic Odontology and Disaster Victim Identification Practices in Australia

64 A BRIEF HISTORY OF FORENSIC ODONTOLOGY AND DISASTER VICTIM IDENTIFICATION PRACTICES IN AUSTRALIA J Taylor The University of Newcastle, Ourimbah, New South Wales, Australia ABSTRACT in multiple fatality incidents. While this Today we consider forensic odontology to be a reputation has been gained from the specialised and reliable method of identification application of forensic odontology in both of the deceased, particularly in multiple fatality single identification and disaster situations incidents. While this reputation has been over a number of years, the professional gained from the application of forensic nature of the discipline and its practices odontology in both single identification and have evolved only recently. disaster situations over a number of years, the professional nature of the discipline and its This paper summarises some of early uses practices have evolved only recently. of forensic odontology internationally and This paper summarises some of early uses of in Australia and discusses the forensic odontology internationally and in development of both forensic odontology Australia and discusses the development of and Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) both forensic odontology and Disaster Victim practices in each of the states and Identification (DVI) practices in each of the territories of Australia. states and territories of Australia. While the identification of victims of mass The earliest accounts of the use of forensic fatality incidents (DVI) is now perceived as odontology in Australia date to the 1920’s and a sub-speciality of human identification, 30’s, and were characterised by inexperienced practitioners and little procedural formality. An this has not always been the case. The organised and semi-formal service commenced development and evolution of forensic in most states during the 1960’s although its odontology identification skills in both use by police forces was spasmodic. -

The Pyjama Girl and Submerged Women, Liminal Voices

The Pyjama Girl and Submerged women, liminal voices: A feminist investigation of feature film screenwriting as creative practice Lezli-An Barrett BA Hons 1st class Fine Art and History of Art (Goldsmiths’ College University of London, 1979) Master of Arts in Screenwriting and Screen Research (London College of Printing, The London Institute, University of the Arts London, 1998) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities English and Cultural Studies (Creative Writing) 2017 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Lezli-An Barrett, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by The University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval #: RA/4/1/2444 This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. -

History of Forensic Odontology in Australia

History of Forensic Odontology in Australia Anthony W Lake (BDS FPFA FICD, Forensic Odontology Unit, University of Adelaide) Forensic Odontology around the world Records indicate that for at least two thousand years the use of dental identification has been recognised. In his writings on the History of Rome around 229 AD Dio Cassius recorded that Agrippina, mother of Nero, in 49AD, had Lollia Paulina , wife of Gaius, murdered and on having the head presented to her did not recognise it until she opened the mouth and inspected the teeth and identified some distinguishing dental features1. Over the centuries many cases have been recorded of body identification using the teeth and dental appliances 2-5 but it was not until a fire on May 4th, 1897 at the Bazar de la Charité in Paris where 126 died, including a number of prominent Parisians of the day, that a scientific approach to dental identification for legal purposes was initiated. Even though it was the Paraguan Consul, Albert Haus, who suggested asking the dentists of the missing to assist in the identification process using their records, it was Oscar Amoëdo, a professor at the ‘Ecole Odontotechnique de Paris, who received the credit. Following publication of his thesis ‘L’Art Dentaire en Médecine Légale’6-8, a text drawn from his studies of the literature, extensive personal knowledge and experiences and material compiled from the disaster of 1897, many considered Amoëdo as the father of Forensic Odontology9. Following World War II there was a need in Europe for identification of war victims, perpetrators of war crimes and those involved in mass disasters. -

Afm Product Guide 2003

3DD ENTERTAINMENT 3DD Entertainment, 190 Camden High Street, London, UK NW1 8QP. Tel: 011.44.207.428.1800. Fax: 011 44 207 428 1818. e-mail: [email protected]. Website: www.3dd-entertainment.co.uk Company Type: Distributor At AFM: Dominic Saville (CEO), Charlotte Parton (Director of Sales), James Anderson (Sales Executive), Acquisition Executive: Dominic Saville (CEO) Office: Suite # 334, Tel: 310.458.6700, Mobile: 44 (0)7961 318 665 Film THE ICEMAN COMETH DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: JOHN FRANKENHEIMER Producer: ELY LANDAU Co-Production Partners: Cast:LEE MARVIN, JEFF BRIDGES, FREDERIC MARCH Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: USA/UK Budget: NOT AVAILABLE Based on acclaimed playwright Eugene O'Neill's brilliant stage drama, the patrons of The Last Chance Saloon gather for an evening to contemplate their lost faith and dreams. Film A DELICATE BALANCE DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: TONY RICHARDSON Producer: ELY LANDAU Co-Production Partners: Cast: KATHARINE HEPBRUN, LEE REMICK, PAUL SCOFIELD Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: USA Budget: NOT AVAILABLE Based on a play by Edward Albee, a dysfunctional couple discovers that they have more than they can handle when a family gathering turns chaotic. Film BUTLEY DRAMA Language: ENGLISH Director: HAROLD PINTER Producer: ELY LANDAU, OTTO PLASCHKES Co-Production Partners: Cast: ALAN BATES, JESSICA TANDY, MICHAEL BYRNE Delivery Status: COMPLETED Year of Production: 1973 Country of Origin: UK Budget: NOT AVAILABLE A self-loathing and misanthropic teacher's life takes a tragic turn when his lover betrays him and his ex-wife remarries, in the screen adaptation of Simon Gray's play. -

Back Matter (PDF)

RECENT ORNITHOLOGICAL LITERATURE, No. 74 Supplement to: TheAuk, Vol.114, No. 4, October1997 • The Ibis, Vol. 139, No. 4, October 19972 Publishedby the AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS'UNION, the BRITISH ORNITHOLOGISTS'UNION, and BIRDS AUSTRALIA CONTENTS New Journals.............................................. 2 General Biology............................................ 41 DiscontinuedJournal ....................................... 2 General .................................................. 41 Behavior and Vocalizations ................................ 2 Afrotropical............................................. 41 Conservation ............................................... 6 Antarctic and Subantarctic .............................. 42 Diseases,Parasites, & Pathology........................... 12 Australasia and Oceania ................................. 42 Distribution ................................................ 13 Europe................................................... 44 General .................................................. 13 Indomalayan............................................. 47 Afrotropical............................................. 13 Nearcftc .................................................. 47 Australasia and Oceania ................................. 14 Neotropical.............................................. 50 Europ•?.................................................. 15 North Africa & Middle East ............................. 50 Indomalayan............................................. 17 Northern Asia & Far East