Democratic Relationships: an Institutional Way of Life With/In the Writing Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

Bloomsbury Adult Catalog Fall 2020

BLOOMSBURY Fall 2020 September – December BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING SEPTEMBER 2020 The Apology Eve Ensler From the bestselling author of The Vagina Monologues—a powerful, life-changing examination of abuse and atonement. Like millions of women, Eve Ensler has been waiting much of her lifetime for an apology. Sexually and physically abused by her father, Eve has struggled her whole life from this betrayal, longing for an honest reckoning from a man who is long dead. After years of work as an anti-violence activist, she decided she would wait no longer; an apology could be imagined, by her, for her, to her. The Apology, written by Eve from her father’s point of view in the words she longed to hear, attempts to transform the abuse she suffered with unflinching truthfulness, compassion, and an expansive vision for the future. Through The Apology, Eve has set out to provide a new way for herself and a BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY possible road for others so that survivors of abuse may finally envision how to / LITERARY be free. She grapples with questions she has sought answers to since she first Bloomsbury Publishing | 9/15/2020 9781635575118 | $16.00 / $22.00 Can. realized the impact of her father’s abuse on her life: How do we offer a doorway Trade Paperback | 128 pages rather than a locked cell? How do we move from humiliation to revelation, from 8.3 in H | 5.5 in W curtailing behavior to changing it, from condemning perpetrators to calling Other Available Formats: them to reckoning? What will it take for abusers to genuinely apologize? Hardcover ISBN: 9781635574388 Remarkable and original, The Apology is an acutely transformational look at how, from the wounds of sexual abuse, we can begin to reemerge and heal. -

Download Issue In

L&L6FCv3.qxd:L&L1/04FC 3/4/08 16:29 Page 1 Labelexpo Americas Sponsor of Volume 29 Issue 6 Dec/Jan 2007 Issue 6 Volume 29 The wider world of narrow web Labelexpo review INDUSTRY-LEADING QUALITY AND INNOVATION FOR SMOOTH SAILING, ALL THE WAY. Part two of L&L’s comprehensive Labelexpo Labels and Labeling technology round-up Analysis How should converters respond to new Braille requirements? Technology When you’re in the middle of a fast-paced run, choppy conditions are the last thing you need to encounter. RotoMetrics flexible dies can keep you on course, with industry-leading quality that outperforms the competition. Our crew of experts can help you determine the flexible die that’s right for you — or choose a multi-level or folding carton specialty die, as well as a full range of durable surface treatments. Developments in solid and Dec/Jan 2007 All are designed to meet your exact needs, plus give you maximum effectiveness flexible dies are covered in and value. Visit us online or contact a RotoMetrics office today to learn more. this feature Coverprintedon SyntheticPaperYUPOFEB250. Combiningthestrengthoffilms World Headquarters (US)+1 636 587 3600 ¥UK +44 (0)1922 610000 ¥Germany withtheprintabilityofpaper +49 6134 72 62 0 www.yupo.com France+33 1 64 79 61 00Australia ¥ +61 3 9358 2000 ¥Canada +1 905 858 3800 www.labelsandlabeling.com | www.labelexpo.com When innovation and partnership meet, anything is possible. At Avery Dennison, we work closely with our customers to turn bright ideas into practical, real-life labelling products. Understanding your business enables us to explore new possibilities and develop innovative decorating and information transfer solutions that can make a signifi cant difference to your bottom line. -

To Download a PDF File of FM 3-05.70

Preface As a soldier, you can be sent to any area of the world. It may be in a temperate, tropical, arctic, or subarctic region. You expect to have all your personal equipment and your unit members with you wherever you go. However, there is no guarantee it will be so. You could find yourself alone in a remote area—possibly enemy territory—with little or no personal gear. This manual provides information and describes basic techniques that will enable you to survive and return alive should you find yourself in such a situation. If you are a trainer, use this information as a base on which to build survival training. You know the areas to which your unit is likely to deploy, the means by which it will travel, and the territory through which it will travel. Read what this manual says about survival in those particular areas and find out all you can about those areas. Read other books on survival. Develop a survival-training program that will enable your unit members to meet any survival situation they may face. It can make the difference between life and death. The proponent of this publication is the United States Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School (USAJFKSWCS). Submit comments and recommended changes to Commander, USAJFKSWCS, ATTN: AOJK-DT-SF, Fort Bragg, NC 28310-5000. Unless this publication states otherwise, masculine nouns and pronouns do not refer exclusively to men. 1 Chapter 1 Introduction This manual is based entirely on the keyword SURVIVAL. The letters in this word can help guide your actions in any survival situation. -

Download (19Mb)

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36265 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. Mosaics of the Self: Kantian Objects and Female Subjects in the Work of Claire Goll and Paula Ludwig Rachel Jones Submitted for the degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Department of Philosophy (Philosophy and Literature) September 1997 II Contents Introduction Journeying into the Darkness 1 Fart One Subjects of Dissolution 17 Chapter One The Dissolution of Woman: Lyotard, Difference and the Postmodem Sublime 18 Chapter Two The Dissolution of Man: German Expressionism and the Post-human Sublime 63 Interlude 125 Chapter 3 Interlude: Another Expressionism 126 Fart Two Manifold Selves 166 Chapter Four Claire Aischmann/ Studei( Go!!: Acrobatic Space-Time 167 Chapter Five The Glass Garden: Mosaic Mirrorings 214 Chapter Six Bodies of Resonance: Eurydice, Music and Darkness 276 Chapter Seven Transformative Touch: The Poetry of Paula Ludwig 315 From Postmodem Patchworks to a Conclusion Mosaics of the Self 362 Appendix 1 377 Appendix 2 384 Appendix 3 388 Bibliography 390 U' Acknowledgements I would like to thank all those, family and friends, who have supported and encouraged me over the last four years. In particular, I would like to thank Valerie Bafico and Mair and Vince Jones for their continual support; my sisters, Beki and Naomi, for theft unflagging encouragement and challenging questions; Catherine Constable, Georgina Paul and Christine Battersby for providing me with endless inspiralion my mother, June Jones, without whom this would not have been written; and AdrianArmstrong, for his endless energy and enthusiasm. -

The Planetary Turn

The Planetary Turn The Planetary Turn Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty- First Century Edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2015 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2015. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The planetary turn : relationality and geoaesthetics in the twenty-first century / edited by Amy J. Elias and Christian Moraru. pages cm Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 978-0-8101-3073-9 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3075-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-8101-3074-6 (ebook) 1. Space and time in literature. 2. Space and time in motion pictures. 3. Globalization in literature. 4. Aesthetics. I. Elias, Amy J., 1961– editor of compilation. II. Moraru, Christian, editor of compilation. PN56.S667P57 2015 809.9338—dc23 2014042757 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Elias, Amy J., and Christian Moraru. The Planetary Turn: Relationality and Geoaesthetics in the Twenty-First Century. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2015. The following material is excluded from the license: Illustrations and an earlier version of “Gilgamesh’s Planetary Turns” by Wai Chee Dimock as outlined in the acknowledgments. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. -

Extended Abstracts

Book of extended abstracts The Fifth Conference of the European Philosophy of Science Association 23 – 26 September 2015 http://www.philsci.eu/epsa15 Duesseldorf Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science (DCLPS) Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf, Germany http://dclps.phil.hhu.de/ EPSA15 is supported by Springer De Gruyter Mentis Harvard University Press Cambridge University Press Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Duesseldorf Center for Logic and Philosophy of Science Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf European Philosophy of Science Association Edited by Alexander Christian, Christian J. Feldbacher, Alexander Gebharter, Nina Retzlaff, Gerhard Schurz & Ioannis Votsis Impressum Heinrich Heine University Duesseldorf Department of Philosophy (Institut fuer Philosophie) Universitaetsstrasse 1, Geb. 24.52 40225 Duesseldorf, Germany Table of Contents Abstracts ......................................................................................................................................1 Plenary Lectures ................................................................................................................................. 1 Symposia & Contributed Papers I ....................................................................................................... 3 Symposia & Contributed Papers II .................................................................................................... 46 Symposia & Contributed Papers III .................................................................................................. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2017 The Laws of Fantasy Remix Matthew J. Dauphin Follow this and additional works at the DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE LAWS OF FANTASY REMIX By MATTHEW J. DAUPHIN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2017 Matthew J. Dauphin defended this dissertation on March 29, 2017. The members of the supervisory committee were: Barry Faulk Professor Directing Dissertation Donna Marie Nudd University Representative Trinyan Mariano Committee Member Christina Parker-Flynn Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To every teacher along my path who believed in me, encouraged me to reach for more, and withheld judgment when I failed, so I would not fear to try again. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ v 1. AN INTRODUCTION TO FANTASY REMIX ...................................................................... 1 Fantasy Remix as a Technique of Resistance, Subversion, and Conformity ......................... 9 Morality, Justice, and the Symbols of Law: Abstract -

Jefferson's Taper

SMU Law Review Volume 73 Issue 2 Article 6 2020 Jefferson’s Taper Jeremy N. Sheff St. John's University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Jeremy N. Sheff, Jefferson’s Taper, 73 SMU L. REV. 299 (2020) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol73/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. JEFFERSON’S TAPER Jeremy N. Sheff* ABSTRACT This Article reports a new discovery concerning the intellectual geneal- ogy of one of American intellectual property law’s most important texts. The text is Thomas Jefferson’s often-cited letter to Isaac McPherson re- garding the absence of a natural right of property in inventions, metaphori- cally illustrated by a “taper” that spreads light from one person to another without diminishing the light at its source. I demonstrate that Thomas Jef- ferson likely copied this Parable of the Taper from a nearly identical pas- sage in Cicero’s De Officiis, and I show how this borrowing situates Jefferson’s thoughts on intellectual property firmly within a natural law theory that others have cited as inconsistent with Jefferson’s views. I further demonstrate how that natural law theory rests on a pre-Enlightenment Classical Tradition of distributive justice in which distribution of resources is a matter of private judgment guided by a principle of proportionality to the merit of the recipient—a view that is at odds with the post-Enlighten- ment Modern Tradition of distributive justice as a collective social obliga- tion that proceeds from an initial assumption of human political equality. -

Eric Laneuville Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Eric Laneuville 电影 串行 (大全) Exposed https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/exposed-5421584/actors Maréchaussée https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mar%C3%A9chauss%C3%A9e-26214860/actors Cry Lusion https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cry-lusion-18644046/actors The Grimm https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-grimm-identity-27070622/actors Identity PTZD https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ptzd-15930037/actors The Inheritance https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-inheritance-26025124/actors å¦ ä¸€é¢ https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/%E5%8F%A6%E4%B8%80%E9%9D%A2-16639708/actors Key Move https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/key-move-29097907/actors Red Badge https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-badge-105095288/actors Red Herring https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-herring-105095322/actors Pink Chanel Suit https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pink-chanel-suit-105095359/actors Like a Redheaded https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/like-a-redheaded-stepchild-105095404/actors Stepchild Little Red Book https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-red-book-105095422/actors The Redshirt https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-redshirt-105095436/actors Ruddy Cheeks https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ruddy-cheeks-105095453/actors Days of Wine and https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/days-of-wine-and-roses-105095500/actors Roses Red Listed https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-listed-105095535/actors Forest Green https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/forest-green-105095568/actors -

Eric Laneuville ̘͙” ˪…˶€ (Ìž'í'ˆìœ¼ë¡Œ)

Eric Laneuville ì˜í ™” 명부 (작품으로) Exposed https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/exposed-5421584/actors Maréchaussée https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mar%C3%A9chauss%C3%A9e-26214860/actors Cry Lusion https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/cry-lusion-18644046/actors The Grimm https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-grimm-identity-27070622/actors Identity PTZD https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ptzd-15930037/actors The Other Side https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-other-side-16639708/actors The Inheritance https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-inheritance-26025124/actors Key Move https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/key-move-29097907/actors The Other Woman https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-other-woman-1050294/actors Red Badge https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-badge-105095288/actors Red Herring https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-herring-105095322/actors Pink Chanel Suit https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/pink-chanel-suit-105095359/actors Like a Redheaded https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/like-a-redheaded-stepchild-105095404/actors Stepchild Little Red Book https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-red-book-105095422/actors The Redshirt https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-redshirt-105095436/actors Ruddy Cheeks https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ruddy-cheeks-105095453/actors Days of Wine and https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/days-of-wine-and-roses-105095500/actors Roses Red Listed https://ko.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/red-listed-105095535/actors -

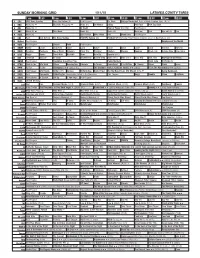

Sunday Morning Grid 1/11/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/11/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Dr. Chris College Basketball Duke at North Carolina State. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) On Money Skiing PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football NFC Divisional Playoff Dallas Cowboys at Green Bay Packers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Employee of the Month 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Revenge of the Nerds 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Pablo Montero Hotel Todo Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B.