Pimentel, Ruth.Pdf (6.296Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventory & Analysis

Inventory & Analysis Overview The Plan’s recommendations will transform the Howard Property from a residential lot into a passive green neighborhood park. The plan provides for quiet, safe woodland setting with carefully renewed native plantings with an internal trail system that connects to the larger Beltline trail that connects to surrounding neighborhoods. Park Description and Context Upper Lawn in 2007 Comprising approximately five acres at 471 Collier Road, the Howard Property is a significant new passive park bounded by Tanyard Creek, Overbrook Drive and Collier Road. Acquired in 2006 to provide the “missing link” for the BeltLine Trail between Tanyard Creek Park and the City of Atlanta’s Bobby Jones Golf Course, the site offers passive opportunities at a neighborhood scale. Trail design by the PATH Foundation, under the auspices of Atlanta BeltLine inc. and the City of Atlanta’s Department of Parks Recreation & Cultural Affairs, was under way spring of 2008. With the assistance of the Trust for Public Land the land assemblage was completed in 2006. Residential structures on the site were demolished in 2007. This Master Plan is to identify and plan for various landscape works to further clean up the site and make it more useable and maintainable. Members of the community expressed a desire to undertake a master planning exercise to identify opportunities for amenities (seating, secondary pathways, plantings, etc.) and management zones (areas for naturalization, passive open lawn space, garden development, etc.) 5 Master Planning Process The Howard Property Master Plan was announced at the BeltLine Subarea Study Group Meeting of May 5, 2008. -

Impact Report 2019

IMPACT REPORT 2019 years 30 Years for the Greener Good Celebrated green tie GALA for the greener good A heartfelt “thank you” to all guests at Park Pride’s Green Tie Gala. Our work engaging communities to activate the power of parks simply would not be possible if it weren’t for the support of people like you: people who are passionate about improving the lives of individuals, strengthening communities, and preserving nature in the city. Special Thanks Honorary Co-Chairs Arthur Blank Sally and Jim Morgens Event Host Dorothy Yates Kirkley And So Many More! Host Committee Gala Patrons Sponsors Community Partners Planning Committee 2 Impact Area Friends of the Park Program Volunteer Program Fiscal Sponsor Program Community Garden Program Park Visioning Program Grants Program Park Pride is in the forefront of any type of conservancy, foundation, and support group that we know of nationally, and they serve as a national model of how cities and supporting nonprofits can work together to demonstrate success in engaging communities in promoting equity, developing environmental and social resiliency, and achieving social justice outcomes through parks. Kellie May Vice President of Programs and Partnerships National Recreation and Park Association “ 3 Supporting Communities 146 Friends of the Park groups supported n 2019, Park Pride’s services and resources reached I218 parks and 146 Friends of the Park groups seeking more for their families and neighborhoods. A Look at Peters Park In 2018, neighbors in Tucker were concerned with the state of William McKinley Peters Park. The amenities were old and outdated, and unsavory activities were prevalent (though hidden from view because invasive plant species had overrun sections of the greenspace). -

November 2012

November 2012 News for Candler Park Your In Town Hometown www.CandlerPark.org Candler Park Candler Park golf Course Neighborhood Organization Named One of Ten Officer Elections “Places in Peril” by LExa KiNg, CPNO MEMbErshiP OffiCEr from the georgia Trust for i think it serves us well to remember why CPNO meets historic Preservation every month and why we go through the exercise The georgia Trust for historic Preservation has annually of seeking people to run for our board of announced its 2013 list of ten Places in Peril in the Directors positions. state, and Candler Park golf Course and clubhouse are included. MissiON Of CPNO: The purpose of the neighborhood organization shall be to promote the common good and “This is the Trust’s eighth annual Places in Peril list,” general welfare in the neighborhood known as Candler said Mark C. McDonald, president and CEO of the Trust. Park in the City of atlanta, georgia. “We hope the list will continue to bring preservation action to georgia’s imperiled historic resources by That said, to agree to serve on the board of Directors highlighting ten representative sites.” of CPNO is a remarkable opportunity and responsibility. as with many volunteer positions, what is seen by most Places in Peril is designed to raise awareness about of the participants of any organization is a small part georgia’s significant historic, archaeological and cultural of the dedication and energy that is expended by the resources, including buildings, structures, districts, leaders. some of the efforts of these volunteers are: archaeological sites and cultural landscapes that are threatened by demolition, neglect, lack of maintenance, • Monthly board and membership meetings, special inappropriate development or insensitive public policy. -

National Register of Histof Jcplacesrmgistration Form

NFS Form 10-900 RECEIVED 2280 OMBNo. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service MAR 1 2 7QQ8 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTOF JCPLACESRMGISTRATION FORM REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibi ______tv for NATIONAL BftflJfeSfijyifilEdistrit :s. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Peachtree Highlands-Peachtree Park Historic District other names/site number Peachtree Highlands Historic District; Peachtree Park 2. Location street & number Roughly bounded by Piedmont Road, Peachtree Road, Georgia Highway 400, and the MARTA north-south rapid transit line city, town Atlanta (N/A ) vicinity of county Fulton code GA 121 state Georgia code GA zip code 30305 ( ) not for publication 3. Classification Ownership of Property: Category of Property: (x) private ( ) building(s) ( ) public-local (x) district ( ) public-state ( ) site ( ) public-federal ( ) structure ( ) object Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: Name of previous listing: Peachtree Highlands Historic District - listed June 5, 1986 (105 contributing buildings). Name of related multiple property listing: N/A Peachtree Highlands-Peachtree Park Historic District, Fulton County, Georgia NPS Form 10-900-a OMB Approved No. -

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP)

City of Atlanta 2016-2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) Community Work Program (CWP) Prepared By: Department of Planning and Community Development 55 Trinity Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30303 www.atlantaga.gov DRAFT JUNE 2015 Page is left blank intentionally for document formatting City of Atlanta 2016‐2020 Capital Improvements Program (CIP) and Community Work Program (CWP) June 2015 City of Atlanta Department of Planning and Community Development Office of Planning 55 Trinity Avenue Suite 3350 Atlanta, GA 30303 http://www.atlantaga.gov/indeex.aspx?page=391 Online City Projects Database: http:gis.atlantaga.gov/apps/cityprojects/ Mayor The Honorable M. Kasim Reed City Council Ceasar C. Mitchell, Council President Carla Smith Kwanza Hall Ivory Lee Young, Jr. Council District 1 Council District 2 Council District 3 Cleta Winslow Natalyn Mosby Archibong Alex Wan Council District 4 Council District 5 Council District 6 Howard Shook Yolanda Adreaan Felicia A. Moore Council District 7 Council District 8 Council District 9 C.T. Martin Keisha Bottoms Joyce Sheperd Council District 10 Council District 11 Council District 12 Michael Julian Bond Mary Norwood Andre Dickens Post 1 At Large Post 2 At Large Post 3 At Large Department of Planning and Community Development Terri M. Lee, Deputy Commissioner Charletta Wilson Jacks, Director, Office of Planning Project Staff Jessica Lavandier, Assistant Director, Strategic Planning Rodney Milton, Principal Planner Lenise Lyons, Urban Planner Capital Improvements Program Sub‐Cabinet Members Atlanta BeltLine, -

Rail-Trail Extension Conceptual Design Study

City of Chamblee Rail-Trail Extension Conceptual Design Study Report | August 2016 Heath & Lineback Engineers, 2016 2390 Canton Rd #200, Marietta, GA 30066 www.heath-lineback.com T: (770) 424-1668 This document has been prepared by Heath & Lineback Engineers, Inc. in a strategic partnership with: • Perez Planning + Design, LLC • Signature Design Reproduction or distribution of this document and its contents is prohibited without the approval of the City of Chamblee Client(s): City of Chamblee Client Contact: Gary Cornell, AICP + Jim Summerbell, AICP Project Manager: Mark Holmberg, P.E. Acknowledgments City of Chamblee City Council R. Eric Clarkson - Mayor John Mesa - District One Leslie C. Robson - District Two Thomas S. Hogan, II - District Three Brian Mock - At Large Seat Darron Kusman - At Large Seat City of Chamblee Administration Jon Walker - City Administrator City of Chamblee Staff Gary A. Cornell, FAICP - Director of Development Jim Summberbell, AICP - Deputy Development Director Heath & Lineback Engineers, Inc. John Heath, P.E - President | Principal Mark Holmberg, P.E. - Vice President | Project Manager Patrick Peters, P.E. - Project Engineer Perez Planning + Design, LLC Carlos F. Perez, PLA - President | Urban Designer Allison Bustin - Project Planner Table of Contents 6 Section 1: Existing Conditions 64 3.3 Focus Area 2 - Restaurant Row 66 3.4 Focus Area 3 - Mercy Care + Walmart + Analysis 70 3.5 Focus Area 4 - Rail-Trail Park 8 1.1 Introduction 80 3.6 Focus Area 5 - Chamblee Senior 8 1.2 Design Study Process Residences 10 -

A Declaration of Interdependence

March 23rd, 2015 | Atlanta Botanical Garden | presented by P arks & people a declaration of interdependence join the conversation on twitter: #PGC15, @Parkpride Cox Enterprises has a long history of being a good corporate citizen. Through Cox Conserves we’re making a positive impact on the environment through our operations and our community partnerships. It’s the steps we take together as one that make a big difference. We’re proud to be the presenting sponsor of Park Pride’s 14th Annual Parks & Greenspace Conference. For more information on Cox Enterprises’ corporate responsibility programs, please visit: www.coxinc.com P arks & people: a declARation of interdePendence Great parks require community involvement and dedication to guarantee their creation, revitalization and activation. The 2015 Parks and Greenspace Conference theme explores the relationship between engaged communities and successful parks. t able of Contents Welcome 2 Venue Map / WiFi 3 Program 4 Keynote Speaker Bios 10 Inspiration Awards 12 Sponsors 14 Connect with Your Community 16 Thank You 17 2016 Parks & Greenspace Conference Back P resented by Sc Hedule overview 7:30 AM Hardin Visitor Center Registration Opens 7:30–8:30 AM Day Hall Continental Breakfast / Networking 8:30–10:25 AM Day Hall Welcome & Opening Plenary Session 10:40 AM–12:00 PM Various Locations Morning Concurrent Sessions 12:00–12:50 PM Day Hall Lunch 12:50–2:00 PM Day Hall Mid-day Plenary Session 2:15–3:30 PM Various Locations Afternoon Concurrent Sessions 3:45–5:00 PM Day Hall Closing Plenary Session & Closing Remarks 5:00 PM Mershon Hall Reception / Networking MtaRCH 23, 2015 | a LANTA BotAnicAl GaRden | 1 w elcome to the 2015 ParkS and GreenspAce confeRence t this year’s Parks and Greenspace Conference, we celebrate the role communities play in making parks great. -

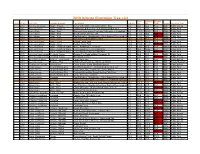

2019 Champion Trees

2019 Atlanta Champion Tree List CIR HEIGHT SPREA Rank YEAR SPECIES COMMON NAME LOCATION CIR (ft) (in) (ft) D (ft) Points Location Type 1 2014 Acer buergerianum Maple - Trident corner of Peachtree Rd and Peachtree Way 2.2 26.0 36.0 18.0 66.5 Public Access 1 2015 Acer japonicum Maple - Japanese Callanwolde Arts Center - in dedication garden area 2.3 27.5 23.2 22.5 56.3 Public Park 1 2011 Acer rubrum Maple - Red McLendon Ave, across from Lake Claire park on boardwalk 9.2 110.0 109.3 52.5 232.5 Public Park 2 2012 Acer rubrum Maple - Red Dearborn Park, Decatur, GA 9.5 114.5 95.2 50.0 222.2 Public Park 3 2010 Acer rubrum Maple - Red East Palisades, Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area8.5 101.5 88.0 45.0 200.8 Public Park 1 2002 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver 310 Robinhood Rd Atlanta 30309 14.9 178.8 85.0 95.0 287.6 Private Residence 1 2010 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver Herbert Taylor Park 13.7 164.0 101.6 91.0 288.4 Public Park 1 2012 Acer saccharinum Maple - Silver Herbert Taylor Park 12.6 151.0 111.0 60.0 277.0 Public Park 1 2014 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar 207 E. Parkwood, Decatur, GA 10.9 131.0 81.8 70.0 230.3 Private Residence 2 2010 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar Lionel Hampton- Beecher Hills Park 8.0 96.0 104.3 52.0 213.3 Public Park 2 2012 Acer saccharum Maple - Southern Sugar Lionel Hampton- Beecher Hills Park 6.2 74.0 119.4 50.0 205.9 Public Park 1 2010 Aesculus hippocastanumChestnut - Horse Decatur City Parks building, Sycamore St. -

Atlanta Community Schoolyards a Project of the 10-Minute Walk Campaign

Atlanta Community Schoolyards A project of the 10-Minute Walk Campaign An Urban Land Institute Technical Assistance Panel July 25, 2019 Atlanta ABOUT ULI – URBAN LAND INSTITUTE As the preeminent, multidisciplinary real estate forum, The Urban Land Institute (ULI) is a nonprofit education and research group supported by its diverse, expert membership base. Our mission is to provide leadership in the responsible use of land and in creating and sus- taining thriving communities worldwide. ULI ATLANTA With over 1,400 members throughout the Atlanta region (Georgia, Alabama & Eastern Ten- nessee), ULI Atlanta is one of the largest and most active ULI District Councils worldwide. We bring together leaders from across the fields of real estate and land use policy to ex- change best practices and serve community needs. We share knowledge through educa- tion, applied research, publishing, electronic media, events and programs. TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE PROGRAM (TAP) Since 1947, the Urban Land Institute has harnessed the technical expertise of its members to help communities solve difficult land use, development, and redevelopment challenges. Technical Assistance Panels (TAPs) provide expert, multidisciplinary, unbiased advice to local governments, public agencies and nonprofit organizations facing complex land use and real estate issues in the Atlanta Region. Drawing from our seasoned professional mem- bership base, ULI Atlanta offers objective and responsible guidance on a variety of land use and real estate issues ranging from site-specific projects to public policy questions. About the 10-Minute Walk Campaign The 10-Minute Walk Campaign is a nationwide movement launched in October 2017 to ensure that there is a great park within a ten-minute walk of every person, in every neighborhood, in every city across the United States. -

Maple Place Apartments Investment 1352 - 1360 North Ave & 1414 Euclid Opportunity Presented by Atlanta, Ga 30307

OFFERING MEMORANDUIM A MULTIFAMILY MAPLE PLACE APARTMENTS INVESTMENT 1352 - 1360 NORTH AVE & 1414 EUCLID OPPORTUNITY PRESENTED BY ATLANTA, GA 30307 FranklinSt.com MAPLE PLACE APARTMENTS | ATLANTA GA CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENT EXCLUSIVELY LISTED BY: This is a confidential Memorandum intended solely for your limited use and benefit in determining whether you desire to express further interest into the acquisition of the Subject Property. Jake Reid Senior Director This Memorandum contains selected information pertaining to the Property and does not purport to be a representation of state of affairs of the Owner or the 404.832.1250 ext. 404 [email protected] Property, to be all-inclusive or to contain all or part of the information which prospective investors may require to evaluate a purchase of real property. All financial projections and information are provided for general reference purposes only and are based on assumptions relating to the general economy, market Ricky Jones conditions, competition, and other factors beyond the control of the Owner or Franklin Street Real Estate Services, LLC. Therefore, all projections, assumptions, Director and other information provided and made herein are subject to material variation. All references to acreages, square footages, and other measurements 404.832.1250 ext. 420 are approximations. Additional information and an opportunity to inspect the Property will be made available to all interested and qualified prospective [email protected] purchasers. Neither the Owner or Franklin Street Real Estate Services, LLC. , nor any of their respective directors, officers, affiliates or representatives are making any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, as to the accuracy or completeness of this Memorandum or any of its contents, and no legal commitment or obligation shall arise by reason of your receipt of this Memorandum or use of its contents; and you are to rely solely on your own investigations and inspections of the Property in evaluating a possible purchase of the real property. -

Atlanta Beltline Redevelopment Plan

Atlanta BeltLine Redevelopment Plan PREPARED FOR The Atlanta Development Authority NOVEMBER 2005 EDAW Urban Collage Grice & Associates Huntley Partners Troutman Sanders LLP Gravel, Inc. Watercolors: Rebekah Adkins, Savannah College of Art and Design Acknowledgements The Honorable Mayor City of Atlanta The BeltLine Partnership Shirley C. Franklin, City of Atlanta Fulton County The BeltLine Tax Allocation District Lisa Borders, President, Feasibility Study Steering Commi�ee Atlanta City Council Atlanta Public Schools The Trust for Public Land Atlanta City Council Members: Atlanta Planning Advisory Board (APAB) The PATH Foundation Carla Smith (District 1) Neighborhood Planning Units (NPU) Friends of the BeltLine Debi Starnes (District 2) MARTA Ivory Young Jr. (District 3) Atlanta Regional Commission Cleta Winslow (District 4) BeltLine Transit Panel Natalyn Archibong (District 5) Anne Fauver (District 6) Howard Shook (District 7) Clair Muller (District 8) Felicia Moore (District 9) C. T. Martin (District 10) Jim Maddox (District 11) Joyce Sheperd (District 12) Ceasar Mitchell (Post 1) Mary Norwood (Post 2) H. Lamar Willis (Post 3) Contents 1.0 Summary 1 7.0 Types of Costs Covered by TAD Funding 2.0 Introduction 5 and Estimated TAD Bond Issuances 77 2.1 The BeltLine Concept 5 7.0.1 Workforce Housing 78 2.2 Growth and Development Context 5 7.0.2 Land Acquisition–Right-of-Way, 2.3 Historic Development 7 Greenspace 78 2.4 Feasibility Study Findings 8 7.0.3 Greenway Design and Construction 78 2.5 Cooperating Partners 9 7.0.4 Park Design and Construction -

Atlanta Business Chronicle

STATE OF THE REGION JANUARY 10-16, 2020 • 36 PAGES • $3.00 SPECIAL SECTION • 25A CULTURE VS. COMFORT Atlanta’s L5P seeks to stay funky amid change Copyright © 2020 American City Business Journals - Not for commercial use INSIDER Delta Air Lines CEO Ed Bastian at Boy Scouts’ Golden Eagle Luncheon. 6A Little Five Points has long been a bastion of counterculture. BYRON E. SMALL ON THE BEAT BY CHRIS FUHRMEISTER | [email protected] CIVIC ATLANTA ignificant changes are coming neighborhoods meet, Little Five Points has at the intersection of Moreland, Euclid Georgia Chamber aims to keep state ‘open for this year to Findley Plaza in Lit- long been a bastion of counterculture. It and McClendon avenues. Trees are scat- business’ in 2020 tle Five Points. Property owners, is increasingly an island in a sea of devel- tered throughout the public space, which is Maria Saporta, 8A landlords and residents are con- opment that, spurred by the construction backed by a long row of businesses such as sidering the cultural future of the of the Atlanta Beltline’s Eastside Trail, has the Porter Beer Bar, Euclid Avenue Yacht Seclectic east-side commercial district as brought a wave of high-dollar commercial Club (a much divier establishment than the REAL ESTATE NOTES well. and residential real estate projects in the past name would indicate), Criminal Records Prized Midtown site Sitting along Moreland Avenue where decade. was sold to Portman Atlanta’s Inman Park and Candler Park Findley Plaza takes up a tenth of an acre L5P CONTINUED ON PAGE 18A Holdings