(Xenostegia Tridentata (L.) DF Austin & Staples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medicinal Practices of Sacred Natural Sites: a Socio-Religious Approach for Successful Implementation of Primary

Medicinal practices of sacred natural sites: a socio-religious approach for successful implementation of primary healthcare services Rajasri Ray and Avik Ray Review Correspondence Abstract Rajasri Ray*, Avik Ray Centre for studies in Ethnobiology, Biodiversity and Background: Sacred groves are model systems that Sustainability (CEiBa), Malda - 732103, West have the potential to contribute to rural healthcare Bengal, India owing to their medicinal floral diversity and strong social acceptance. *Corresponding Author: Rajasri Ray; [email protected] Methods: We examined this idea employing ethnomedicinal plants and their application Ethnobotany Research & Applications documented from sacred groves across India. A total 20:34 (2020) of 65 published documents were shortlisted for the Key words: AYUSH; Ethnomedicine; Medicinal plant; preparation of database and statistical analysis. Sacred grove; Spatial fidelity; Tropical diseases Standard ethnobotanical indices and mapping were used to capture the current trend. Background Results: A total of 1247 species from 152 families Human-nature interaction has been long entwined in has been documented for use against eighteen the history of humanity. Apart from deriving natural categories of diseases common in tropical and sub- resources, humans have a deep rooted tradition of tropical landscapes. Though the reported species venerating nature which is extensively observed are clustered around a few widely distributed across continents (Verschuuren 2010). The tradition families, 71% of them are uniquely represented from has attracted attention of researchers and policy- any single biogeographic region. The use of multiple makers for its impact on local ecological and socio- species in treating an ailment, high use value of the economic dynamics. Ethnomedicine that emanated popular plants, and cross-community similarity in from this tradition, deals health issues with nature- disease treatment reflects rich community wisdom to derived resources. -

Review Article Progress on Research and Development of Paederia Scandens As a Natural Medicine

Int J Clin Exp Med 2019;12(1):158-167 www.ijcem.com /ISSN:1940-5901/IJCEM0076353 Review Article Progress on research and development of Paederia scandens as a natural medicine Man Xiao1*, Li Ying2*, Shuang Li1, Xiaopeng Fu3, Guankui Du1 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Hainan Medical University, Haikou, P. R. China; 2Haikou Cus- toms District P. R. China, Haikou, P. R. China; 3Clinical College of Hainan Medical University, Haikou, P. R. China. *Equal contributors. Received March 19, 2018; Accepted October 8, 2018; Epub January 15, 2019; Published January 30, 2019 Abstract: Paederia scandens (Lour.) (P. scandens) has been used in folk medicines as an important crude drug. It has mainly been used for treatment of toothaches, chest pain, piles, hemorrhoids, and emesis. It has also been used as a diuretic. Research has shown that P. scandens delivers anti-nociceptive, anti-inflammatory, and anti- tumor activity. Phytochemical screening has revealed the presence of iridoid glucosides, volatile oils, flavonoids, glucosides, and other metabolites. This review provides a comprehensive report on traditional medicinal uses, chemical constituents, and pharmacological profiles ofP. scandens as a natural medicine. Keywords: P. scandens, phytochemistry, pharmacology Introduction plants [5]. In China, for thousands of years, P. scandens has been widely used to treat tooth- Paederia scandens (Lour.) (P. scandens) is a aches, chest pain, piles, hemorrhoids, and perennial herb belonging to the Paederia L. emesis, in addition to being used as a diuretic. genus of Rubiaceae. It is popularly known as Research has shown that P. scandens has anti- “JiShiTeng” due to the strong and sulfurous bacterial effects [6]. -

Potential Biological Control Agents of Skunkvine, Paederia Foetida (Rubiaceae), Recently Discovered in Thailand and Laos

Session 4 Target and Agent Selection 199 Potential Biological Control Agents of Skunkvine, Paederia foetida (Rubiaceae), Recently Discovered in Thailand and Laos M. M. Ramadan, W. T. Nagamine and R. C. Bautista State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture, Division of Plant Industry, Plant Pest Control Branch, 1428 South King Street, Honolulu, HAWAII 96814, USA [email protected] Abstract The skunkvine, Paederia foetida L., also known as Maile pilau in Hawaii, is an invasive weed that smothers shrubs, trees, and native flora in dry to wet forests. It disrupts perennial crops and takes over landscaping in moist to wet areas on four Hawaiian Islands. Skunk-vine is considered a noxious weed in southern United States (Alabama and Florida) and also an aggressive weed in Brazil, New Guinea, Christmas and Mauritius Islands. Chemical control is difficult without non-target damage as the vine mixes up with desirable plants. Biological control is thought to be the most suitable option for long term management of the weed in Hawaii and Florida. Skunk-vine and most species of genus Paederia are native to tropical and subtropical Asia, from as far as India to Japan and Southeast Asia. There are no native plants in the tribe Paederieae in Hawaii and Florida and the potential for biological control looks promising. A recent survey in October-December 2010, after the rainy season in Thailand and Laos, confirmed the presence of several insect herbivores associated with P. foetida and three other Paederia species. A leaf- tying moth (Lepidoptera: Crambidae), two hawk moths (Lepidoptera: Sphingidae), a herbivorous rove beetle (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae), a chrysomelid leaf beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae), a sharpshooter leafhopper (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae), and a leaf-sucking lace bug (Hemiptera: Tingidae) were the most damaging to the vine during the survey period. -

Marble-Like Chûnnam in the 18Th- and 19Th-Century Madras Presidency

ARTICLES IJHS | VOL 55.1 | MARCH 2020 Marble-like chûnnam in the 18th- and 19th-century Madras Presidency Anantanarayanan Raman∗ Charles Sturt University, PO Box 883, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. (Received 25 September 2019; revised 07 November 2019) Abstract Lime (calcined limestone), referred as çûnam and çûṇṇam (‘chûnnam’) was used in the Indian subconti- nent for ages. In the Tamizh country, lime was referred as çûṇṇāmpu. The nature and quality chûnnam used in the Madras presidency are formally recorded in various published reports by the British either living in or visiting Madras from the 18th century. All of them consistently remark that the quality of chûnnam used in building human residences and other buildings was of superior quality than that used for the same purpose elsewhere in India. The limestone for making chûnnam was extracted from (i) inland quarries and (ii) beached seashells. The latter was deemed of superior quality. In the Tamizh country in particular, a few other biological materials were added to lime mortar to achieve quicker and better hardening. In the Madras presidency, builders and bricklayers, used to add jaggery solution, egg albumin, clarified butter, and freshly curdled yoghurt, and talc schist (balapong) to the lime mortar.Many of the contemporary construction engineers and architects are presently loudly talking on the validity and usefulness of using lime mortar, embellished with plant fibres and plant extracts, supplemented by traditional practice of grinding. Key words: Çûṇṇāmbu, Jaggery, John Smith, Kaḍukkāi, Limestone Mortar, Magnesite, Portland Cement, Seashells, Vegetable Material. 1 Introduction mortar instead of a mixer, for better compres- sive strength and long-lasting life. -

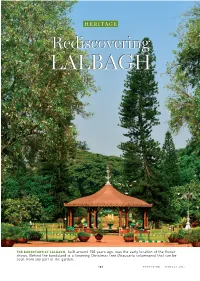

Rediscovering LALBAGH

HERITAGE Rediscovering LALBAGH THE BANDSTAND AT LALBAGH, built around 150 years ago, was the early location of the flower shows. Behind the bandstand is a towering Christmas tree (Araucaria columnaris) that can be seen from any part of the garden. 101 F RONTLINE . A PRIL 23, 2021 V.K. Thiruvady’s book on Lalbagh, arguably one of India’s best public gardens, provides an evocative account of this fantastic arboreal world in Bengaluru and comprehensively traces its history from its early days. Text by VIKHAR AHMED SAYEED and photographs by K. MURALI KUMAR FOR a long period in its modern history, Bengaluru was known by the touristy moniker “Garden City” as verdant patches of greenery enveloped its fledgling urbanity. Little traffic plied on its long stretches of tree- lined promenades, which were ubiquitous, and residents were proud of their well-maintained home gardens, which evoked a salubrious feeling among visitors who came from hotter climes. Bengaluru’s primary selling point has always been its pleasant weather, and it was because of this and its extensive network of public parks and the toddling pace of life its residents led that Karnataka’s capital city was also alluringly, but tritely, known as a “pensioner’s paradise”. Over the past few decades, as Bengaluru exploded into a megalopolis and acquired the glitzy honorific of India’s “Silicon City”, its dated appellations have fallen out of use, but several public parks, big and small, still straddle the city’s busy boulevards, harking back to an era when Bengaluru was known for its greenery. Of the many green spaces in the city, the two large public gardens of THE GLASS HOUSE AT LALBAGH was completed in 1889 and was meant to be a miniature version of the Crystal DURING THE Republic Day Cubbon Park and Lalbagh stand out and continue to hectare) Lalbagh, which lies just a few kilometres away, Palace in Hyde Park, London. -

27 Skunk Vine

27 SKUNK VINE R. W. Pemberton and P. D. Pratt U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, Invasive Plant Research Laboratory, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, USA tion of livestock, however, are unknown (Gann and PEST STATUS OF WEED Gordon, 1998). In urban landscapes, this vine en- Skunk vine, Paederia foetida L. (Fig. 1), is a recently twines branches of woody ornamental plants and also recognized weedy vine of natural areas in Florida that spreads horizontally through lawns, rooting at the is spreading into other parts of the southern United nodes (Martin, 1995). In westcentral Florida, P. States. The weed, which is native to Asia, appears to foetida is considered the most troublesome weed have the potential to spread well beyond the South along roadside right-of-ways (W. Moriaty, pers. to the northeastern states. Control of the plant by comm.), and it also entangles power lines and associ- chemical or mechanical means damages valued veg- ated structures (Martin, 1995). etation supporting the vine. Skunk vine is a Category On the island of Hawaii, P. foetida is a very se- I Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council weed (Langeland rious weed in nurseries producing ornamental foli- and Craddock Burks, 1998), a listing that groups the age plants (Pemberton, pers. obs.). The weed infests plant with the most invasive weed species in Florida. field plantings used for propagation. Control of the weed is very difficult because stock plants are easily injured if herbicides are applied. At times, growers have had to abandon or destroy stock plants that have become overgrown by skunk vine. -

Wallich and His Contribution to the Indian Natural History

Rheedea Vol. 26(1) 13–20 2016 Wallich and his contribution to the Indian natural history Ranee Om Prakash Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Various activities of Nathaniel Wallich, especially those that connect with Indian natural history are briefly reviewed. Wallich rose to a naturalist of international standard from a prisoner of war in discovering the riches of the then British India and reporting to the learned world. He established a close network of leading experts in the field of natural history and exchanged plant materials for the benefit of both the donor and receiving countries. During his superintendence of the then Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta, which prevailed nearly three decades, Wallich introduced useful plants from across the world and elevated the status of the Garden as one of the finest in the world, published over 8,000 new species, about 142 genera of plants and established a world class herbarium. An initiative funded by the World Collections Programme has tried to give due recognition to Wallich towards his contribution to natural history by hosting a website (www.kew. org/wallich). This is a joint collaborative project between Kew Gardens, The Natural History Museum, London and The British Library with additional inputs from the Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden, Howrah and The National Archives of India, New Delhi. Keywords: Collections, Herbarium, Online Resource, Wallich Catalogue Introduction located next to the river and use similar irrigation systems. Kew Garden was built in 1759 and the Nathaniel Wallich (1785–1854) spent 34 years in Calcutta Botanic Garden was established in 1787. -

Rubiaceae): Evolution of Major Clades, Development of Leaf-Like Whorls, and Biogeography

TAXON 59 (3) • June 2010: 755–771 Soza & Olmstead • Molecular systematics of Rubieae Molecular systematics of tribe Rubieae (Rubiaceae): Evolution of major clades, development of leaf-like whorls, and biogeography Valerie L. Soza & Richard G. Olmstead Department of Biology, University of Washington, Box 355325, Seattle, Washington 98195-5325, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Valerie L. Soza, [email protected] Abstract Rubieae are centered in temperate regions and characterized by whorls of leaf-like structures on their stems. Previous studies that primarily included Old World taxa identified seven major clades with no resolution between and within clades. In this study, a molecular phylogeny of the tribe, based on three chloroplast regions (rpoB-trnC, trnC-psbM, trnL-trnF-ndhJ) from 126 Old and New World taxa, is estimated using parsimony and Bayesian analyses. Seven major clades are strongly supported within the tribe, confirming previous studies. Relationships within and between these seven major clades are also strongly supported. In addition, the position of Callipeltis, a previously unsampled genus, is identified. The resulting phylogeny is used to examine geographic distribution patterns and evolution of leaf-like whorls in the tribe. An Old World origin of the tribe is inferred from parsimony and likelihood ancestral state reconstructions. At least eight subsequent dispersal events into North America occurred from Old World ancestors. From one of these dispersal events, a radiation into North America, followed by subsequent diversification in South America, occurred. Parsimony and likelihood ancestral state reconstructions infer the ancestral whorl morphology of the tribe as composed of six organs. Whorls composed of four organs are derived from whorls with six or more organs. -

Differentiation of Hedyotis Diffusa and Common Adulterants Based on Chloroplast Genome Sequencing and DNA Barcoding Markers

plants Article Differentiation of Hedyotis diffusa and Common Adulterants Based on Chloroplast Genome Sequencing and DNA Barcoding Markers Mavis Hong-Yu Yik 1,† , Bobby Lim-Ho Kong 1,2,†, Tin-Yan Siu 2, David Tai-Wai Lau 1,2, Hui Cao 3 and Pang-Chui Shaw 1,2,4,* 1 Li Dak Sum Yip Yio Chin R & D Center for Chinese Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong, China; [email protected] (M.H.-Y.Y.); [email protected] (B.L.-H.K.); [email protected] (D.T.-W.L.) 2 Shiu-Ying Hu Herbarium, School of Life Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong, China; [email protected] 3 Research Center for Traditional Chinese Medicine of Lingnan (Southern China) and College of Pharmacy, Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China; [email protected] 4 State Key Laboratory of Research on Bioactivities and Clinical Applications of Medicinal Plants (CUHK), The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-39431363; Fax: +852-26037246 † The authors contributed equally. Abstract: Chinese herbal tea, also known as Liang Cha or cooling beverage, is popular in South China. It is regarded as a quick-fix remedy to relieve minor health problems. Hedyotis diffusa Willd. (colloquially Baihuasheshecao) is a common ingredient of cooling beverages. H. diffusa is also used to treat cancer and bacterial infections. Owing to the high demand for H. diffusa, two common adulterants, Hedyotis brachypoda (DC.) Sivar and Biju (colloquially Nidingjingcao) and Hedyotis corymbosa (L.) Lam. -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt. -

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/S12038-013-9316-9

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/s12038-013-9316-9 Natural history in India during the 18th and 19th centuries RAJESH KOCHHAR Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohali 140 306, Punjab (Email, [email protected]) 1. Introduction courier. We shall focus on India-based Europeans who built a scientific reputation for themselves; there were of course European access to India was multi-dimensional: The others who merely served as suppliers. merchant-rulers were keen to identify commodities that could be profitably exported to Europe, cultivate commercial plants in India that grew outside their possessions, and find 2. Tranquebar and Madras (1768–1793) substitutes for drugs and simples that were obtained from the Americas. The ever-increasing scientific community in As in geography, the earliest centre for botanical and zoo- Europe was excited about the opportunities that the vast logical research was South India. Europe-dictated scientific landmass of India offered in natural history studies. On their botany was begun in India by a direct pupil of Linnaeus not part, the Christianity enthusiasts in Europe viewed European in the British possessions but in the tiny Danish enclave of rule in India as a godsend for propagating the Gospel in the Tranquebar, which though of little significance as far as East. These seemingly diverse interests converged at various commerce or geo-politics was concerned, came to play an levels. Christian missionaries as a body were the first edu- extraordinary role in the cultural and scientific history of cated Europeans in India. As in philology, they were pio- India. neers in natural history also. -

Paederia Foetida

Paederia foetida Paederia foetida Skunk vine Introduction The genus Paederia contains 20-30 species worldwide, generally distributed in the tropics of Asia. In China, eleven species and one variety have been reported, occurring mainly in the south and southwest China[47]. Species of Paederia in China Paederia foetida growth habit. (Photo by Ken Scientific Name Scientific Name A. Langeland, University of Florida.) P. cavaleriei Lévl. P. scandens (Lour.) Merr. P. foetida L. P. spectatissima H. Li ex C. Puff Paederia scandens (Lour.) Merr., P. lanuginosa Wall. P. stenobotrya Merr. fever vine, is more common than P. laxiflora Merr. ex Li P. stenophylla Merr. P. foetida. It is a twining vine with a length of 3-5 m. It grows on hillsides, P. pertomentosa Merr. ex Li P. yunnanensis (Lévl.) Rehd. in forests, along forest edges, along P. praetermissa C. Puff streamsides, and twining on trees at elevations of 300-2,000 m in Anhui, underside pubescent. Conspicuous Taxonomy Fujian, Guangdong, Sichuan, Taiwan, stipules are ovate lanceolate and 2-3 [47] Family: Rubiaceae Yunnan, and Zhejiang . mm in length, with two notches in the Genus: Paederia L. top. Flowering terminally or from leaf Although there are some differences axils, panicles reach a length of 6-18 Description in appearance between Paederia cm. Corollas are violet, 12-16 mm long, Paederia foetida, a twining vine-like foetida and P. scandens, recent work and commonly hair-covered with short shrub, may release a strong fetid odor has reduced P. scandens to a synonym lobes. Topped with a conical flower discs [125] when bruised.