The Botanical Writings of Maria Graham”: 44-58

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The China of Santa Cruz”: the Culture of Tea in Maria Graham's

“The China of Santa Cruz”: The Culture of Tea in Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (Article) NICOLLE JORDAN University of Southern Mississippi he notion of Brazilian tea may sound like something of an anomaly—or impossibility—given the predominance of Brazilian coffee in our cultural T imagination. We may be surprised, then, to learn that King João VI of Portugal and Brazil (1767–1826) pursued a project for the importation, acclimatization, and planting of tea from China in his royal botanic garden in Rio de Janeiro. A curious episode in the annals of colonial botany, the cultivation of a tea plantation in Rio has a short but significant history, especially when read through the lens of Maria Graham’s Journal of a Voyage to Brazil (1824). Graham’s descriptions of the tea garden in this text are brief, but they amplify her thorough-going enthusiasm for the biodiversity and botanical innovation she encountered— and contributed to—in South America. Such enthusiasm for the imperial tea garden echoes Graham’s support for Brazilian independence, and indeed, bolsters it. In 1821 Graham came to Brazil aboard HMS Doris, captained by her husband Thomas, who was charged with protecting Britain’s considerable mercantile interests in the region. As a British naval captain’s wife, she was obliged to uphold Britain’s official policy of strict neutrality. Despite these circumstances, her Journal conveys a pro-independence stance that is legible in her frequent rhapsodies over Brazil’s stunning flora and fauna. By situating Rio’s tea plantation within the global context of imperial botany, we may appreciate Graham’s testimony to a practice of transnational plant exchange that effectively makes her an agent of empire even in a locale where Britain had no territorial aspirations. -

Marble-Like Chûnnam in the 18Th- and 19Th-Century Madras Presidency

ARTICLES IJHS | VOL 55.1 | MARCH 2020 Marble-like chûnnam in the 18th- and 19th-century Madras Presidency Anantanarayanan Raman∗ Charles Sturt University, PO Box 883, Orange, NSW 2800, Australia. (Received 25 September 2019; revised 07 November 2019) Abstract Lime (calcined limestone), referred as çûnam and çûṇṇam (‘chûnnam’) was used in the Indian subconti- nent for ages. In the Tamizh country, lime was referred as çûṇṇāmpu. The nature and quality chûnnam used in the Madras presidency are formally recorded in various published reports by the British either living in or visiting Madras from the 18th century. All of them consistently remark that the quality of chûnnam used in building human residences and other buildings was of superior quality than that used for the same purpose elsewhere in India. The limestone for making chûnnam was extracted from (i) inland quarries and (ii) beached seashells. The latter was deemed of superior quality. In the Tamizh country in particular, a few other biological materials were added to lime mortar to achieve quicker and better hardening. In the Madras presidency, builders and bricklayers, used to add jaggery solution, egg albumin, clarified butter, and freshly curdled yoghurt, and talc schist (balapong) to the lime mortar.Many of the contemporary construction engineers and architects are presently loudly talking on the validity and usefulness of using lime mortar, embellished with plant fibres and plant extracts, supplemented by traditional practice of grinding. Key words: Çûṇṇāmbu, Jaggery, John Smith, Kaḍukkāi, Limestone Mortar, Magnesite, Portland Cement, Seashells, Vegetable Material. 1 Introduction mortar instead of a mixer, for better compres- sive strength and long-lasting life. -

Maria Graham Artista-Autora-Viajante Eclectic Journeys, Permanencies and Their Writings: Maria Graham Artist- Author-Traveller

MIDAS Museus e estudos interdisciplinares 11 | 2020 Dossier temático: "Perspetivas sobre o museu eclético" Viagens ecléticas, residências e obras: Maria Graham artista-autora-viajante Eclectic journeys, permanencies and their writings: Maria Graham artist- author-traveller Maria de Fátima Lambert Edição electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/midas/2222 DOI: 10.4000/midas.2222 ISSN: 2182-9543 Editora: Alice Semedo, Paulo Simões Rodrigues, Pedro Casaleiro, Raquel Henriques da Silva, Ana Carvalho Refêrencia eletrónica Maria de Fátima Lambert, « Viagens ecléticas, residências e obras: Maria Graham artista-autora- viajante », MIDAS [Online], 11 | 2020, posto online no dia 19 novembro 2020, consultado no dia 21 novembro 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/midas/2222 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ midas.2222 Este documento foi criado de forma automática no dia 21 novembro 2020. Midas is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 International License Viagens ecléticas, residências e obras: Maria Graham artista-autora-viajante 1 Viagens ecléticas, residências e obras: Maria Graham artista-autora- viajante Eclectic journeys, permanencies and their writings: Maria Graham artist- author-traveller Maria de Fátima Lambert NOTA DO EDITOR Artigo recebido a 12.02.2019 Aprovado para publicação a 15.03.2020 Resiliência nas viagens e pensamento de Maria Graham 1 Albert Babeau escrevia em 1885: «La manière de voyager est bien plus en rapport qu'on ne pourrait le croire avec l’état social et politique des nations» (1885, 11). Cerca de 60 anos antes, as viagens realizadas por Maria Graham (1785-1842) anunciavam-se como eixos privilegiados para a transformação de si pelo confronto de alteridade e divergência; eram imprescindíveis para a consolidação formativa do indivíduo (Venayre 2012, 10). -

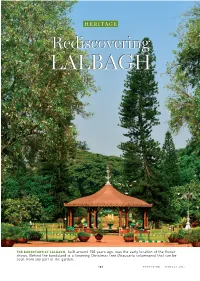

Rediscovering LALBAGH

HERITAGE Rediscovering LALBAGH THE BANDSTAND AT LALBAGH, built around 150 years ago, was the early location of the flower shows. Behind the bandstand is a towering Christmas tree (Araucaria columnaris) that can be seen from any part of the garden. 101 F RONTLINE . A PRIL 23, 2021 V.K. Thiruvady’s book on Lalbagh, arguably one of India’s best public gardens, provides an evocative account of this fantastic arboreal world in Bengaluru and comprehensively traces its history from its early days. Text by VIKHAR AHMED SAYEED and photographs by K. MURALI KUMAR FOR a long period in its modern history, Bengaluru was known by the touristy moniker “Garden City” as verdant patches of greenery enveloped its fledgling urbanity. Little traffic plied on its long stretches of tree- lined promenades, which were ubiquitous, and residents were proud of their well-maintained home gardens, which evoked a salubrious feeling among visitors who came from hotter climes. Bengaluru’s primary selling point has always been its pleasant weather, and it was because of this and its extensive network of public parks and the toddling pace of life its residents led that Karnataka’s capital city was also alluringly, but tritely, known as a “pensioner’s paradise”. Over the past few decades, as Bengaluru exploded into a megalopolis and acquired the glitzy honorific of India’s “Silicon City”, its dated appellations have fallen out of use, but several public parks, big and small, still straddle the city’s busy boulevards, harking back to an era when Bengaluru was known for its greenery. Of the many green spaces in the city, the two large public gardens of THE GLASS HOUSE AT LALBAGH was completed in 1889 and was meant to be a miniature version of the Crystal DURING THE Republic Day Cubbon Park and Lalbagh stand out and continue to hectare) Lalbagh, which lies just a few kilometres away, Palace in Hyde Park, London. -

Wallich and His Contribution to the Indian Natural History

Rheedea Vol. 26(1) 13–20 2016 Wallich and his contribution to the Indian natural history Ranee Om Prakash Department of Life Sciences, The Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Various activities of Nathaniel Wallich, especially those that connect with Indian natural history are briefly reviewed. Wallich rose to a naturalist of international standard from a prisoner of war in discovering the riches of the then British India and reporting to the learned world. He established a close network of leading experts in the field of natural history and exchanged plant materials for the benefit of both the donor and receiving countries. During his superintendence of the then Royal Botanic Garden, Calcutta, which prevailed nearly three decades, Wallich introduced useful plants from across the world and elevated the status of the Garden as one of the finest in the world, published over 8,000 new species, about 142 genera of plants and established a world class herbarium. An initiative funded by the World Collections Programme has tried to give due recognition to Wallich towards his contribution to natural history by hosting a website (www.kew. org/wallich). This is a joint collaborative project between Kew Gardens, The Natural History Museum, London and The British Library with additional inputs from the Acharya Jagdish Chandra Bose Indian Botanic Garden, Howrah and The National Archives of India, New Delhi. Keywords: Collections, Herbarium, Online Resource, Wallich Catalogue Introduction located next to the river and use similar irrigation systems. Kew Garden was built in 1759 and the Nathaniel Wallich (1785–1854) spent 34 years in Calcutta Botanic Garden was established in 1787. -

Department of History

H.H. THE RAJAHA’S COLLEGE (AUTO), PUDUKKOTTAI - 622001 Department of History II MA HISTORY HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E THIRD SEMESTER 18PHS7 MA HISTORY SEMESTER : III SUB CODE : 18PHS7 CORE COURSE : CCVIII CREDIT : 5 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1947 C.E Objectives ● To understand the colonial hegemony in India ● To Inculcate the knowledge of solidarity shown by Indians against British government ● To know about the social reform sense through the historical process. ● To know the effect of the British rule in India. ● To know the educational developments and introduction of Press in India. ● To understand the industrial and agricultural bases set by the British for further developments UNIT – I Decline of Mughals and Establishment of British Rule in India Sources – Decline of Mughal Empire – Later Mughals – Rise of Marathas – Ascendancy under the Peshwas – Establishment of British Rule – the French and the British rivalry – Mysore – Marathas Confederacy – Punjab Sikhs – Afghans. UNIT – II Structure of British Raj upto 1857 Colonial Economy – Rein of Rural Economy – Industrial Development – Zamindari system – Ryotwari – Mahalwari system – Subsidiary Alliances – Policy on Non intervention – Doctrine of Lapse – 1857 Revolt – Re-organization in 1858. UNIT – III Social and cultural impact of colonial rule Social reforms – English Education – Press – Christian Missionaries – Communication – Public services – Viceroyalty – Canning to Curzon. ii UNIT – IV India towards Freedom Phase I 1885-1905 – Policy of mendicancy – Phase II 1905-1919 – Moderates – Extremists – terrorists – Home Rule Movement – Jallianwala Bagh – Phase III 1920- 1947 – Gandhian Era – Swaraj party – simon commission – Jinnah‘s 14 points – Partition – Independence. UNIT – V Constitutional Development from 1773 to 1947 Regulating Act of 1773 – Charter Acts – Queen Proclamation – Minto-Morley reforms – Montague Chelmsford reforms – govt. -

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/S12038-013-9316-9

Perspectives DOI 10.1007/s12038-013-9316-9 Natural history in India during the 18th and 19th centuries RAJESH KOCHHAR Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, Mohali 140 306, Punjab (Email, [email protected]) 1. Introduction courier. We shall focus on India-based Europeans who built a scientific reputation for themselves; there were of course European access to India was multi-dimensional: The others who merely served as suppliers. merchant-rulers were keen to identify commodities that could be profitably exported to Europe, cultivate commercial plants in India that grew outside their possessions, and find 2. Tranquebar and Madras (1768–1793) substitutes for drugs and simples that were obtained from the Americas. The ever-increasing scientific community in As in geography, the earliest centre for botanical and zoo- Europe was excited about the opportunities that the vast logical research was South India. Europe-dictated scientific landmass of India offered in natural history studies. On their botany was begun in India by a direct pupil of Linnaeus not part, the Christianity enthusiasts in Europe viewed European in the British possessions but in the tiny Danish enclave of rule in India as a godsend for propagating the Gospel in the Tranquebar, which though of little significance as far as East. These seemingly diverse interests converged at various commerce or geo-politics was concerned, came to play an levels. Christian missionaries as a body were the first edu- extraordinary role in the cultural and scientific history of cated Europeans in India. As in philology, they were pio- India. neers in natural history also. -

1 Earthquake Ecologists I

Earthquake ecologists I – James Graham Cooper James Graham Cooper roamed Washington Territory as a young naturalist shortly before the Civil War. Near Astoria he observed the remains of trees that are important today as clues to earthquake hazards. Cooper came here from New York in 1853. He had sought and gained a position as surgeon and naturalist with the Issac Stevens railroad survey. His survey party was commanded by George McClellan and was provisioned at Fort Vancouver by Ulysses Grant. The Smithsonian Institution provided support for follow-up work, which centered on collecting museum specimens at Willapa (then Shoalwater) Bay. The remains of drowned trees caught Cooper’s eye in 1854 and 1855. His journal tells of spruce stumps in growth position in the banks of a tidal creek near Chinook. His railroad report, extolling western red cedar as a source of durable shingles, describes dead trunks of “this species only” standing in Willapa Bay tidal marshes. Cooper reasoned that these standing trees had died when tides overflowed sinking land. Today is has become clear that this sinking takes place during earthquakes, when a leading edge of North America lurches tens of feet toward Asia. The shift stretches solid rock, which thins like a pulled rubber band. The thinning lowers coastal land several feet. Tides overflow the freshly sunken land, killing thousands of trees. Sudden changes in land level routinely accompany certain kinds of earthquakes. Examples from Alaska and Chile will be recounted in two subsequent Nature Notes. SOURCES A biography of James Graham Cooper (1830–1902) includes a timeline of his career and a comprehensive list of his published and unpublished works1. -

Maria Graham’S Account of the Earthquake in Chile in 1822

36 by M. Kölbl-Ebert Observing orogeny — Maria Graham’s account of the earthquake in Chile in 1822 Geologische Staatssammlung München, Luisenstraße 37, 80333 München, Germany. “As to ignorance of the science of Geology, Mrs. [Graham] con- means of earthquakes, — any rehabilitation of Maria Graham being fesses it: and, perhaps, that circumstance, and her consequent only a by-product. indifference to all theories connected with it, render her unbiassed The case became more and more entangled by circumstantial testimony of the more value.” (Callcott, formerly Graham, 1835) evidence, in which the testimony of witnesses for both parties was found to conflict. But then came a lucky break, if only for Maria Gra- In November 1822, part of the Chilean coast was devas- ham and Charles Lyell, but not for the poor people of Chile... While tated by an intense earthquake. This report of geological the jury was still out, in 1835 the “criminal” struck again, only to be phenomena by Maria Graham, later Callcott (1785– caught 'in flagrante' by a special task force in the area at that time 1842) — being one of the earliest detailed descriptions “The Beagle-Expedition”, which included the “private detective” dealing with geologically relevant facts — gave rise to a Charles Darwin, who accidentally was at the right place and just in time to settle the case. So, as we will see, the “criminal” was finally vituperative debate lasting several years at the Geologi- found “guilty” but — because this is not a simple story about “good- cal Society of London about the effects of earthquakes ies” and “badies” — for the wrong reasons! and their role in mountain building. -

History of Science and Technology in India

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN INDIA By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 1 CONTENT HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN INDIA Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Science and Technology- The Beginning 1. Development in different branches of Science in Ancient India: 03-28 Astronomy, Mathematics, Engineering and Medicine. 2. Developments in metallurgy: Use of Copper, Bronze and Iron in 29-35 Ancient India. 3. Development of Geography: Geography in Ancient Indian Literature. 36-44 Unit-II Developments in Science and Technology in Medieval India 1. Scientific and Technological Developments in Medieval India; 45-52 Influence of the Islamic world and Europe; The role of maktabs, madrasas and karkhanas set up. 2. Developments in the fields of Mathematics, Chemistry, Astronomy 53-67 and Medicine. 3. Innovations in the field of agriculture - new crops introduced new 68-80 techniques of irrigation etc. Unit-III. Developments in Science and Technology in Colonial India 1. Early European Scientists in Colonial India- Surveyors, Botanists, 81-104 Doctors, under the Company‘s Service. 2. Indian Response to new Scientific Knowledge, Science and 105-116 Technology in Modern India: 3. Development of research organizations like CSIR and DRDO; 117-141 Establishment of Atomic Energy Commission; Launching of the space satellites. Unit-IV. Prominent scientist of India since beginning and their achievement 1. Mathematics and Astronomy: Baudhayan, Aryabhtatta, Brahmgupta, 142-158 Bhaskaracharya, Varahamihira, Nagarjuna. 2. Medical Science of Ancient India (Ayurveda & Yoga): Susruta, 159-173 Charak, Yoga & Patanjali. 3. Scientists of Modern India: Srinivas Ramanujan, C.V. Raman, 174-187 Jagdish Chandra Bose, Homi Jehangir Bhabha and Dr. -

Elevación De Montañas a Través De Intrusiones Plutónicas Y La Controversia Geológica Vivida Por Maria Graham

O EOL GIC G A D D A E D C E I H C I L E O S F u n 2 d 6 la serena octubre 2015 ada en 19 Elevación de montañas a través de intrusiones plutónicas y la controversia geológica vivida por Maria Graham Carolina Silva Parejas Universidad Nacional Andrés Bello, Av. República 252, Santiago, Chile email: [email protected] Resumen. Hutton y posteriormente Lyell postulaban una Maria Graham, inglesa temporalmente avecindada en estrecha relación causal entre terremotos y erupciones Chile, fue una productiva escritora y cronista de sus volcánicas, considerándolos manifestaciones alternativas numerosos viajes, notable pintora, dibujante y naturalista, de los procesos de intrusión magmática y expansión a se declaraba ignorante de las teorías geológicas. Sin gran profundidad, agrupados bajo el título general de embargo, su descripción del alzamiento continental como procesos ígneos. consecuencia del terremoto de 1822 que le tocó vivir en Maria Graham, cronista inglesa, describió de manera Quintero, fue considerada de tal importancia que Charles notable el alzamiento continental como consecuencia del Lyell la incluyó en su Principles of Geology (Lyell, 1830) terremoto de 1822 que le tocó vivir en Quintero, siendo y fue la primera mujer en publicar en Transactions of the citada por Lyell y atacada por el presidente de la Geological Society of London. Geological Society of London. Esto aún cuando sus reportes no pretendían reforzar la teoría de Lyell y son El creciente uso por Lyell y otros del argumento de la completamente razonables desde un punto de vista elevación de cadenas de montañas por la intrusión de actual. -

Missionaries and Clergymen As Botanists in India and Pakistan

TAXON 31(1): 57-64. FEBRUARY 1982 MISSIONARIES AND CLERGYMEN AS BOTANISTS IN INDIA AND PAKISTAN Ralph R. Stewart' Until recent years in India the Central Government only supported a few botanists who served in the Botanical Survey of India. Pakistan does not have a Botanical Survey and has only one botanist who is in charge of the new National Herbarium. A large amount of the plant collecting which was done in India from the days of the East India Company to the present was the work of amateurs living in India or by foreigners of many nations. The only history in which one can find the names of many of these workers is that of Isaac H. Burkill (1870-1965), who served in the Indian Forest Service for many years and was the first to publish a check-list of the plants of Baluchistan in 1909. Unfortunately he intentionally stopped his history at 1900, omitting hundreds of names of people who worked after that date. Only a few references to events after 1900 slipped in. His history entitled "Chapters on the history of botany in India" was published in parts in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 1957-63, and in 1965 was published in book form by the Botanical Survey of India in Calcutta. It is a mine of information but the ore is often so scattered that it is hard to find. It is surprising how many people in India were interested in plant collecting, even in the early days, while the East India Company was in control i.e, before 1857.