The Arbёresh Culture: an Ace in the Hole, in the Heart Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Long Lasting Differences in Civic Capital: Evidence from a Unique Immigration Event in Italy

Long Lasting Differences in Civic Capital: Evidence from a Unique Immigration Event in Italy. E. Bracco, M. De Paola and C. Green Abstract We examine the persistence of cultural differences focusing on the Arberesh in Italy. The Arberesh are a linguistic and ethnic minority living in the south of Italy. They settled in Italy at the end of the XV century, following the invasion of the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire. Using a large dataset from the Italian parliamentary elections of the lower chamber of the Parliament, taking place from 1946 to 2008, we compare turnout in Arberesh municipalities with turnout in indigenous municipalities located in the same geographical areas. We also use two alternative different indicators of social capital like turnout at referendum and at European Parliament Elections. We find that in Arberesh municipalities turnout and compliance rates are higher compared to indigenous municipalities located in the same area. 1 I. INTRODUCTION A range of evidence now exists that demonstrates the relationship between social capital and a range of important socio-economic outcomes. Using a variety of proxies, social capital has been shown to have predictive power across a range of domains, including economic growth (Helliwell and Putnam, 1995; Knack and Keefer, 1997; Zak and Knack, 2001), trade (Guiso et al., 2004), well- functioning institutions (Knack, 2002), low corruption and crime (Uslaner, 2002; Buonanno et al., 2009) and well functioning financial markets (Guiso et al., 2004a). While this literature demonstrates large and long-lived within and across country differences in values, social and cultural norms rather less is known about the origins of these differences. -

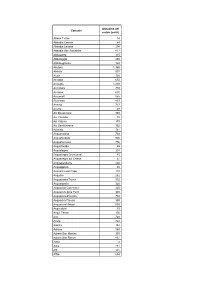

Comune Altitudine Del Centro

Altitudine del Comune centro (metri) Abano Terme 14 Abbadia Cerreto 64 Abbadia Lariana 204 Abbadia San Salvatore 822 Abbasanta 315 Abbateggio 450 Abbiategrasso 120 Abetone 1.388 Abriola 957 Acate 199 Accadia 650 Acceglio 1.200 Accettura 770 Acciano 600 Accumoli 855 Acerenza 833 Acerno 727 Acerra 28 Aci Bonaccorsi 365 Aci Castello 15 Aci Catena 170 Aci Sant'Antonio 302 Acireale 161 Acquacanina 734 Acquafondata 926 Acquaformosa 756 Acquafredda 55 Acqualagna 204 Acquanegra Cremonese 45 Acquanegra sul Chiese 31 Acquapendente 420 Acquappesa 80 Acquarica del Capo 110 Acquaro 262 Acquasanta Terme 392 Acquasparta 320 Acquaviva Collecroce 425 Acquaviva delle Fonti 300 Acquaviva d'Isernia 730 Acquaviva Picena 359 Acquaviva Platani 558 Acquedolci 15 Acqui Terme 156 Acri 720 Acuto 724 Adelfia 154 Adrano 560 Adrara San Martino 355 Adrara San Rocco 431 Adria 4 Adro 271 Affi 191 Affile 684 Afragola 43 Africo 15 Agazzano 187 Agerola 630 Aggius 514 Agira 650 Agliana 46 Agliano Terme 263 Agliè 315 Aglientu 420 Agna 3 Agnadello 94 Agnana Calabra 210 Agnone 830 Agnosine 465 Agordo 611 Agosta 382 Agra 655 Agrate Brianza 165 Agrate Conturbia 337 Agrigento 230 Agropoli 24 Agugliano 203 Agugliaro 13 Aicurzio 230 Aidomaggiore 250 Aidone 800 Aielli 1.021 Aiello Calabro 502 Aiello del Friuli 18 Aiello del Sabato 425 Aieta 524 Ailano 260 Ailoche 569 Airasca 257 Airola 270 Airole 149 Airuno 222 Aisone 834 Ala 180 Alà dei Sardi 663 Ala di Stura 1.080 Alagna 92 Alagna Valsesia 1.191 Alanno 307 Alano di Piave 308 Alassio 6 Alatri 502 Alba 172 Alba Adriatica 5 Albagiara -

D'amato Arch. Antonio Vania

CURRICULUM P ROFESSIONALE INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Integrato con Allegato N ( art. 267 c.3 D.P.R. 207/2010) Nome Professionista D’Amato Arch. Antonio Vania Indirizzo Studio Contrada Prospero - 88060 Montauro (Cz) Professionale Indirizzo di residenza Via Veneto, 17 88068 Soverato (Cz) Telefono Cell. 338.7523995- 324.0599766 - tel. 0967-23108 - fax 0967-23108 E-mail [email protected] Pec [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Luogo e data di nascita Locri (RC) 13.11.1961 Codice Fiscale DMT NNV 61S 13D 976N Partita I.V.A. 02041530797 Lingue Inglese ( livello scolastico) Professione Architetto Condizione Professionale Libero Professionista - in forma singola Organizzazione Tecnica Titolare di studio tecnico adeguatamente attrezzato per la progettazione e direzione di opere di edilizia generale. In particolare lo studio risulta equipaggiato a livello sia hardware che software per lo sviluppo di qualsiasi livello e fase di progettazione con elevate capacità organizzative nell’ambito di gruppi progettuali stabilendo ottimi rapporti interpersonali . Diploma Istituto Tecnico Statale per Geometri Soverato con votazione 48/60 Titolo di Laurea Architettura Università di Roma “La Sapienza” Votazione 110/110 e lode 18.7.1991 Abilitazione Università degli Studi di Roma “La Sapienza” 1 novembre 1991 Iscrizione Albo Ordine degli Architetti di Roma n. 10126 dal 6 maggio 1993 Iscrizione Albo Ordine degli Architetti di Catanzaro n. 1188 dal 6 febbraio 1996 Iscrizione Albo Albo Collaudatori Tecnici Regione Calabria n. 1668 Spec. 1 e 11 Iscrizione Albo N. CZ1188175 Elenco Ministero Interni Legge 818/84 Competenze Informatiche Windows, Microsoft Office, Autocad, Arten, Revit, Internet Explorer, Concant ( Contabilità Lavori) Sicant ( Sicurezza nei Cantieri) Epix ( Efficienza Energetica) SuoNus ( Isolamento Acustico Edifici) Curriculum Professionale Arch. -

Acollection of Correspondence

© 2012 Capuchin Friars of Australia. All Rights Reserved. A COLLECTION OF CORRESPONDENCE Some Letters … and other things, from Sixteenth Century Italy in their original languages Bernardo, ben potea bastarvi averne Co’l dolce dir, ch’a voi natura infonde, Qui dove ‘l re de’ fiume ha più chiare onde, Acceso i cori a le sante opre eterne; Ché se pur sono in voi pure l’interne Voglie, e la vita al destin corrisponde, Non uom di frale carne e d’ossa immonde, Ma sète un voi de le schiere sperne. Or le finte apparenze, e ‘l ballo, e ‘l suono, Chiesti dal tempo e da l’antica usanza, A che così da voi vietate sono? Non fôra santità,capdox fôra arroganza Tôrre il libero arbitrio, il maggior dono Che Dio ne diè ne la primera stanza.1 Compiled by Paul Hanbridge Fourth edition, formerly “A Sixteenth Century Carteggio” Rome, 2007, 2008, Dec 2009 1 “Bernardo, it should be enough for you / With that sweet speech infused in you by Nature, / To light our hearts to high eternal works, / Here where the King of Rivers flows most clearly. / Since your own inner wishes are sincere, / And your own life reflects a pure intent, / You’re ra- ther an inhabitant of heaven. /As to these masquerades, dances, and music, /Sanctioned by time and by ancient custom - /Why do you now forbid them in your sermons? /Holiness it is not, but arrogance to take away free will, the highest gift/ Which God bestowed on us from the begin- ning.” Tullia d’Aragona (c. -

Diocesi Di Cosenza - Bisignano Ufficio Vii Ambito Territoriale Di Cosenza

MIUR - UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA CALABRIA DIOCESI DI COSENZA - BISIGNANO UFFICIO VII AMBITO TERRITORIALE DI COSENZA SCUOLA SUPERIORE Classi ORE 0RE Comune ist. Rif. Cod. ist. Rif. Denominazione ist. Rif. Codice Denominazione Indirizzo Comune Alunni Classi Ore Docente Titolare 0RE Tit articolate Utilizz Diocesi CSRI06101D IPSIA "SALVATORE CREA" ACRI VIA SALVATORE SCERVINI N. 115 ACRI 235 13 13 13 CSIS06100T IIS ACRI "IPSIA-ITI" CSTF06101A ITI ACRI VIA SALVATORE SCERVINI N. 115 ACRI 162 8 8 8 CSTD07000T ITCG "FALCONE" ACRI VIA PADRE GIACINTO DA BELMONTE N. 35 ACRI 435 20 20 GROCCIA SERGIO 18 2 ACRI CSTD07000T ITCG "FALCONE" ACRI CSTD070507 SERALE SIRIO ITCG "FALCONE" ACRI VIA PADRE GIACINTO DA BELMONTE N.35 ACRI 214 10 10 10 CSPC01801V LICEO CLASSICO "V. JULIA" VIA A. DE GASPERI, S.N.C. ACRI 152 8 8 8 CSIS01800G IIS ACRI LC - LS "V. JULIA" CSPS018012 LICEO SCIENTIFICO "V. JULIA" ACRI VIA A. DE GASPERI, S.N.C. ACRI 307 14 14 14 CSRI01401X IPSIA AMANTEA VIA SAN ANTONIO AMANTEA 437 22 22 CONFORTI ANNAMARIA 2 20 CSIS014008 IIS AMANTEA "LS-IPSIA" CSPS01401P LS AMANTEA VIA SAN ANTONIO AMANTEA 393 16 16 CONFORTI ANNAMARIA 16 0 AMANTEA CSTD04701T ITC " C. MORTATI" AMANTEA VIA STROMBOLI - S.S. 18 AMANTEA 370 17 17 17 CSIS04700G IIS AMANTEA "ITC-ITI" CSTF047014 ITI AMANTEA VIA E. NOTO AMANTEA 102 5 5 5 BELVEDERE MARITTIMO CSPM070003 IM "T. CAMPANELLA" BELVEDERE M. CSPM070003 IM "T. CAMPANELLA" BELVEDERE M. VIA ANNUNZIATA, 4 BELVEDERE MARITTIMO 562 26 26 26 IIS BISIGNANO "ITI-LS" CSTF01601C ITI BISIGNANO VIA RIO SECCAGNO BISIGNANO 146 8 8 ROSE DOMENICO 8 0 BISIGNANO CSIS01600X IIS BISIGNANO "ITI-LS" CSPC016017 LC LUZZI LUZZI 117 6 6 SMURRA PASQUALE 6 0 IIS BISIGNANO "ITI-LS" CSPS01601A LS BISIGNANO VIA RIO SECCAGNO BISIGNANO 172 10 10 ROSE DOMENICO 10 0 CSTD04901D ITCG "MAJORANA" CASTROLIBERO VIA ALDO CANNATA, 1 CASTROLIBERO 278 14 14 DE VICO GIUSEPPINA 14 0 4 DE VICO GIUSEPPINA 4 0 CASTROLIBERO CSIS049007 I.I.S. -

Of Time, Honor, and Memory: Oral Law in Albania

Oral Tradition, 23/1 (2008): 3-14 Of Time, Honor, and Memory: Oral Law in Albania Fatos Tarifa This essay provides a historical account of the role of oral tradition in passing on from generation to generation an ancient code of customary law that has shaped and dominated the lives of northern Albanians until well into the mid-twentieth century. This traditional body of customary law is known as the Kode of Lekë Dukagjini. It represents a series of norms, mores, and injunctions that were passed down by word of mouth for generations and reputedly originally formulated by Lekë Dukagjini, an Albanian prince and companion-in-arms to Albania’s national hero, George Kastriot Skanderbeg (1405-68). Lekë Dukagjini ruled the territories of Pulati, Puka, Mirdita, Lura, and Luma in northern Albania—known today as the region of Dukagjini—until the Ottoman armies seized Albania’s northernmost city of Shkodër in 1479. Throughout the past five to six centuries this corpus of customary law has been referred to as Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, Kanuni i Malsisë (the Code of the Highlands), or Kanuni i maleve (the Code of the Mountains). The “Code” is an inexact term, since Kanun, deriving from the Greek kanon, simultaneously signifies “norm,” “rule,” and “measure.” The Kanun, but most particularly the norm of vengeance, or blood taking, as its standard punitive apparatus, continue to this day to be a subject of historical, sociological, anthropological, and juridical interest involving various theoretical frames of reference from the dominant trends of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries to today. The Kanun of Lekë Dukagjini was not the only customary law in Albania. -

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order Online

UNDER ORDERS: War Crimes in Kosovo Order online Table of Contents Acknowledgments Introduction Glossary 1. Executive Summary The 1999 Offensive The Chain of Command The War Crimes Tribunal Abuses by the KLA Role of the International Community 2. Background Introduction Brief History of the Kosovo Conflict Kosovo in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Kosovo in the 1990s The 1998 Armed Conflict Conclusion 3. Forces of the Conflict Forces of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Yugoslav Army Serbian Ministry of Internal Affairs Paramilitaries Chain of Command and Superior Responsibility Stucture and Strategy of the KLA Appendix: Post-War Promotions of Serbian Police and Yugoslav Army Members 4. march–june 1999: An Overview The Geography of Abuses The Killings Death Toll,the Missing and Body Removal Targeted Killings Rape and Sexual Assault Forced Expulsions Arbitrary Arrests and Detentions Destruction of Civilian Property and Mosques Contamination of Water Wells Robbery and Extortion Detentions and Compulsory Labor 1 Human Shields Landmines 5. Drenica Region Izbica Rezala Poklek Staro Cikatovo The April 30 Offensive Vrbovac Stutica Baks The Cirez Mosque The Shavarina Mine Detention and Interrogation in Glogovac Detention and Compusory Labor Glogovac Town Killing of Civilians Detention and Abuse Forced Expulsion 6. Djakovica Municipality Djakovica City Phase One—March 24 to April 2 Phase Two—March 7 to March 13 The Withdrawal Meja Motives: Five Policeman Killed Perpetrators Korenica 7. Istok Municipality Dubrava Prison The Prison The NATO Bombing The Massacre The Exhumations Perpetrators 8. Lipljan Municipality Slovinje Perpetrators 9. Orahovac Municipality Pusto Selo 10. Pec Municipality Pec City The “Cleansing” Looting and Burning A Final Killing Rape Cuska Background The Killings The Attacks in Pavljan and Zahac The Perpetrators Ljubenic 11. -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Senato Della Repubblica Xiv Legislatura

BOZZA SENATO DELLA REPUBBLICA XIV LEGISLATURA N. 1108 DISEGNODILEGGE d'iniziativa del senatore TREMATERRA COMUNICATO ALLA PRESIDENZA IL 6 FEBBRAIO 2002 Istituzione della provincia di Castrovillari TIPOGRAFIA DEL SENATO (1400) Atti parlamentari±2± Senato della Repubblica ± N. 1108 XIV LEGISLATURA ± DISEGNI DI LEGGE E RELAZIONI - DOCUMENTI Onorevoli Senatori. ± Il territorio dell'i- della creazione della provincia di Castrovil- stituenda provincia si caratterizza per essere lari, ad iniziare dal disegno di legge Buffone la risultante di tre zone interne ben distinte ed altri, e fino ai diversi disegni di legge d'i- orograficamente, ma tipologicamente assai niziativa dell'onorevole Belluscio (atti Ca- simili: la zona del Pollino, la zona dell'Alto mera n. 4042 e n. 436, rispettivamente, della Ionio e la zona della Valle dell'Esaro. Sono VIII e IX legislatura), del senatore Covello tre aree, che a moÁ di trifoglio convergono (atto Senato n. 694, X legislatura) degli ono- sul piuÁ grande centro urbano del comprenso- revoli Saraceni ed altri (atto Camera n. 6394, rio: Castrovillari. XIII legislatura). L'istituzione della provincia di Castrovil- Le ragioni storiche sono tante, ma al di laÁ lari in questo comprensorio della Calabria di esse sono la valenza del territorio, le sue settentrionale ha origini molto lontane. Infatti tradizioni, la sua cultura, le sue risorse natu- tale antica aspirazione eÁ basata su un co- rali a favorire la possibilitaÁ di istituire in stante riconoscimento che sin dal lontano questo lembo di terra calabrese una nuova 1806 fu espresso da Giuseppe Bonaparte provincia. Si consideri, infatti, che: che, nella ripartizione amministrativa del Re- l'istituenda provincia di Castrovillari eÁ gno di Napoli, scelse Castrovillari come sede ricompresa quasi per intero nel Parco nazio- di uno dei quattro capoluoghi di distretto in nale del Pollino, uno dei parchi piuÁ grandi provincia di Cosenza. -

Shoreline Evolution and Modern Beach Sand Composition Along a Coastal Stretch of the Tyrrhenian Sea, Southern Italy Consuele Morrone and Fabio Ietto*

Morrone and Ietto Journal of Palaeogeography (2021) 10:7 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00088-y Journal of Palaeogeography ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access Shoreline evolution and modern beach sand composition along a coastal stretch of the Tyrrhenian Sea, southern Italy Consuele Morrone and Fabio Ietto* Abstract This contribution focuses on a multidisciplinary research showing the geomorphological evolution and the beach sand composition of the Tyrrhenian shoreline between Capo Suvero promontory and Gizzeria Lido village (Calabria, southern Italy). The aim of the geomorphological analysis was to reconstruct the evolutionary shoreline stages and the present-day sedimentary dynamics along approximately 6 km of coastline. The results show a general trend of beach nourishment during the period 1870–2019. In this period, the maximum shoreline accretion value was estimated equal to + 900 m with an average rate of + 6.5 m/yr. Moreover, although the general evolutionary trend is characterized by a remarkable accretion, the geomorphological analysis highlighted continuous modifications of the beaches including erosion processes. The continuous beach modifications occurred mainly between 1953 and 1983 and were caused mainly by human activity in the coastal areas and inside the hydrographic basins. The beach sand composition allowed an assessment of the mainland petrological sedimentary province and its dispersal pattern of the present coastal dynamics. Petrographic analysis of beach sands identified a lithic metamorphi-clastic petrofacies, characterized by abundant fine-grained schists and phyllites sourced from the crystalline terrains of the Coastal Range front and carried by the Savuto River. The sand is also composed of a mineral assemblage comparable to that of the Amato River provenance. -

Imaging After Maratea 2015 Rotondo

Raduno Annuale Gruppo Regione Basilicata con la partecipazione del Gruppo Regione Calabria Convegno Nazionale Congiunto delle Sezioni di: 8-9 Ecografia Ottobre Mezzi di Contrasto 9-10 Etica e Radiologia Forense Ottobre Radiologia Addominale Gastroenterologica Presidente Onorario A. Rotondo Presidenti L. Romanini - R. Farina - P. Cerro - A. Pinto Coordinatori L. Brunese - R. Grassi - M. Nardella MARATEA 8-10 Ottobre 2015 GRUPPO REGIONALE BASILICATA Presidente M. Nardella Consiglieri R. Brigida - M.I. Lancellotti - C. Turchetti SEZIONE di ECOGRAFIA Presidente R. Farina Consiglieri G. Argento - V. Cantisani - M. Valentino - M. Zappia SEZIONE di MEZZI di CONTRASTO Presidente L. Romanini Consiglieri A. Basile - M. Consalvo - S. Merola - A.A. Stabile Janora SEZIONE di ETICA e RADIOLOGIA FORENSE Presidente A. Pinto Consiglieri E. Cossu - G. Guglielmi - E. Vianello SEZIONE di RADIOLOGIA ADDOMINALE GASTROENTEROLOGICA Presidente P. Cerro Consiglieri M.C. Bellucci - F. Fontana - M.R. Fracella - A. Reginelli CONVEGNO NAZIONALE CONGIUNTO delle Sezioni di ECOGRAFIA MEZZI di CONTRASTO EVENTO 1 ore 14.00 Inaugurazione ore 17.15 II SESSIONE ore 8.30 III SESSIONE ore 11.30 Inaugurazione II SESSIONE III SESSIONE Presidente SIRM C. Masciocchi SONOELASTOGRAFIA Refresher Course: Presidente SIRM C. Masciocchi ERRORE DIAGNOSTICO, SOVRADIAGNOSI IMAGING INTEGRATO del TUMORE del COLON-RETTO Presidente del Gruppo Regionale SIRM Basilicata M. Nardella Presidente: L. Barozzi US vs. RM imaging nel follow up delle patologie di... Presidente Sez. di Studio Etica e Radiologia Forense SIRM A. Pinto e RADIOLOGIA DIFENSIVA ore 9.00 Refresher Course: Presidente Sezione di Studio Ecografia SIRM R. Farina Moderatori: D. Maroscia - A. Basile Presidente: A. Maggialetti Presidente Sez. di Studio Radiol. Addom. -

Amato, L'ultimo Feudo

Amato, l'ultimo feudo Amato è uno tra i tanti centri urbani poco conosciuti della Calabria, situato in una parte alla montagna, caratterizzata da denominazione di Amato, quan- centrale della regione, lungo il un ricco patrimonio boschivo, in do gli ultimi abitanti, sopravvis- tratto del raccordo autostradale, prevalenza querce, cirri, casta- suti al continuo dilagare delle più conosciuto come SS 280 dei gni; molte sono le sorgenti pre- tempeste alluvionali ed all'as- Due Mari che collega il Tirreno senti nella zona, ricche di acque salto di feroci predatori, si ritira- e lo Jonio, nel punto più stretto minerali, alcune con poteri natu- rono sulle alture dell'attuale della Calabria, l’Istmo di S. rali, dagli effetti particolarmente città. Eufemia, inserito, geografica- diuretici. La popolazione è Amato cominciò ad espandersi mente, tra il Comune di attualmente di circa 1000 abi- nel IX e nell'XI sec d.C. con l'ar- Serrastretta e quello di Miglierina tanti e come gli altri paesi del rivo dei Normanni che fortifica- ed occupa una superficie di oltre circondario ha subito la piaga rono il territorio con la costruzio- 2.000 ettari. dell'emigrazione. Attualmente è ne di castelli tra Nicastro, E' facilmente raggiungibile ed è abitato prevalentemente da per- Feroleto, Maida e naturalmente equidistante da Catanzaro e sone anziane, in compenso è il anche ad Amato. Lamezia Terme. Gode di un otti- classico paese a "misura d'uo- Amato appare ufficialmente sui mo clima ed è un territorio piut- mo". documenti storici nell’anno tosto vario, che va dalla collina La storia di Amato vanta origini 1060, quale feudo disabitato, di antichissime, la cui fondazione proprietà di Costanza d’Altavilla.