Historical Uses of the Middle and Upper Rogue River, Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Our Publications Online 24/7/365 at ALWAYS HONORING OUR TRUE HEROES WE BACK OUR BLUE

JEFFERSON BACKROADS Read our publications online 24/7/365 at www.JeffersonBackroads.com ALWAYS HONORING OUR TRUE HEROES WE BACK OUR BLUE A New State of Mind Wholesale & Retail Accessories for Jeffersonians JeffersonOutfitters.com Hildy Langewis 800-337-7389 - [email protected] Welcome Aboard! TABLE OF CONTENTS: THANK YOU! This happy little local 3 ADVERTISING RATES & INFO publication is made possible ONLY thanks to 9 BREWERIES AND DISTILLERIES - LOCAL our Honored Advertisers who graciously place their ADs with us. Our beloved writers, readers 15 DUNSMUIR RAILROAD DEPOT NEWS & EVENTS & subscribers complete the 10 EVENTS - JUST A FEW LOCAL HAPPENINGS circle... 13 GRANNY HAMMOND’S 100TH BIRTHDAY Keeping your 29 & 31 MAPS Business & Events on our 32-33 QUILTING STORIES, EVENTS, PHOTOS & INFO Community’s Radar is our 25 SENIOR CITIZENS INFO Best Pride & 8 STORY: BACKROADS ADVENTURES Joy! 26 STORY: INSPIRATIONS FROM THE FOREST We Positively LOVE what we 22 STORY: NORTHERN KLAMATH CO. HISTORY & EVENTS do. Sharing YOUR business 18 STORY: STITCHING IN THE DITCH - QUILTING is OUR 30 STORY: TAWANDA FARMS - LAMB & SHEEP WOOL Business. 12 & 25 VETERANS EVENTS - INFO & SERVICES Cover Image - Campsite at Butt Lake near Chester, California Photo by M. Fain Jefferson Backroads is proudly published for Law Abiding Citizens, our fellow Independent, Hard Working, Old School, Patriotic American Rebels who live in or travel through our Rugged & Beautiful State of Jefferson Region. The same true INDEPENDENT NATURE and OLD SCHOOL ESSENCE of “The State of Jefferson” can be found in Small Towns all across Rural America. We are proudly keeping our Patriotic American Spirit Alive. -

Lost in Coos

LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Golden Falls Publishing LOST IN COOS Other books by Lionel Youst Above the Falls, 1992 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, 1997 with William R. Seaburg, Coquelle Thompson, Athabaskan Witness, 2002 She’s Tricky Like Coyote, (paper) 2002 Above the Falls, revised second edition, 2003 Sawdust in the Western Woods, 2009 Cover photo, Army C-46D aircraft crashed near Pheasant Creek, Douglas County – above the Golden and Silver Falls, Coos County, November 26, 1945. Photo furnished by Alice Allen. Colorized at South Coast Printing, Coos Bay. Full story in Chapter 4, pp 35-57. Quoted phrase in the subtitle is from the subtitle of Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, by Orville Dodge (Salem, OR: Capital Printing Co., 1898). LOST IN COOS “Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures” of Searches and Rescues on Coos River, Coos County, Oregon 1871 to 2000 by Lionel Youst Including material by Ondine Eaton, Sharren Dalke, and Simon Bolivar Cathcart Golden Falls Publishing Allegany, Oregon Golden Falls Publishing, Allegany, Oregon © 2011 by Lionel Youst 2nd impression Printed in the United States of America ISBN 0-9726226-3-2 (pbk) Frontier and Pioneer Life – Oregon – Coos County – Douglas County Wilderness Survival, case studies Library of Congress cataloging data HV6762 Dewey Decimal cataloging data 363 Youst, Lionel D., 1934 - Lost in Coos Includes index, maps, bibliography, & photographs To contact the publisher Printed at Portland State Bookstore’s Lionel Youst Odin Ink 12445 Hwy 241 1715 SW 5th Ave Coos Bay, OR 97420 Portland, OR 97201 www.youst.com for copies: [email protected] (503) 226-2631 ext 230 To Desmond and Everett How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. -

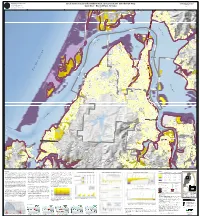

Tsunami Inundation Map for Coos

G E O L O G Y F A N O D STATE OF OREGON T Tsunami Inundation Map Coos-05 N M I E N DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES M E T R R A Tsunami Inundation Maps for Coos Bay - North Bend, A www. OregonGeology.org L Local Source (Cascadia Subduction Zone) Tsunami Inundation Map P I E Coos County, Oregon N D D Larry Givens, Governing Board Chair U N S O T Vicki S. McConnell, Director and State Geologist G R E Plate 1 I R E S O Don WT. Lewis, Assistant Director Coos Bay - North Bend, Oregon Rachel R. Lyles Smith, Project Operations Manager 2012 1937 Ian P. Madin, Chief Scientist 124°20'0"W 124°18'0"W 124°16'0"W 124°14'0"W 124°12'0"W L N TRANS-PACIFIC LN I C I F C A R O B I N R D - P 43°26'0"N S N D A R R T E V O C N N N L A D D OV E R W O J 100 S W A L L O W R D E A ! S T B A Y R D North Bay RFPD M Jordan A L L A R D L N Cove 43°26'0"N ¤£101 R O S E M T N L N 100 C o o 25 City of North Bend "7 s E . C . R D B "5 M C C L U R G L N 200 a 100 y 25 EAST BAY RD y L N E E City of North Bend S a R U O B C City of Coos Bay G O L F D s F E R R Y R o ¤£101 E V C A A o City of Coos Bay R L S O R R N P 25 H O R T S I S 100 M C N L I N A R I O North W R Pony E S P V E E A O Bend A I R R ! L P 100 T Fire N O Slough W R SHERMAN AVE T W E I L A V N Y Y A B 200 L O O P C O L O R A D O A V E O O D City of North Bend A R B AY S T O M L A O P C L E L E A F F S T F L O R I D A A V E M A P L E S T H AY E S S T A R T H U R S T J O H N S O N S T M O N TA N A A V E D C O N N E C T I C U T A V E T R S ¤£101 L L W E D A X A M E MCPHERSON AVE H U N I O N A V E L -

Coos Bay BCS Number: 47-8

Coos Bay BCS number: 47-8 ***NOTE: The completion of this site description is still in progress by our Primary Contact (listed below). However, if you would like to contribute additional information to this description, please contact the Klamath Bird Observatory at [email protected]. Site description author(s) Jennifer Powers Danielle Morris, Research and Monitoring Team, Klamath Bird Observatory Primary contact for this site Mike Graybill, South Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve Manager. Telephone: 541-888-5558 ext. 24, e-mail: [email protected]. Site location (UTM) Datum: NAD83, Zone: 10, Easting: 394143, Northing: 4802686 General description The Coos Bay estuary covers 54 square miles of open channels and tide flats located near the towns of the Coos Bay and North Bend on the southern Oregon coast. The estuary ranges between a mile and a mile and a half wide. A 42 ft. deep, sixteen-mile long ship channel is maintained from the harbor entrance to the Port of Coos Bay. Numerous slough systems and freshwater channels flow into Coos Bay. The narrow estuary is maintained at its mouth by two rock jetties extending from North Spit on the north and Coos Head on the south. From the harbor entrance the main channel bears northward past the communities of Charleston, Barview and Empire, then east around the city of North Bend, and south past downtown Coos Bay. At Coos Bay the channel bears east to the mouth of the Coos River. About two miles upstream the river divides into the Millicoma River on the left and the South Fork of the Coos River on the right. -

Timing of In-Water Work to Protect Fish and Wildlife Resources

OREGON GUIDELINES FOR TIMING OF IN-WATER WORK TO PROTECT FISH AND WILDLIFE RESOURCES June, 2008 Purpose of Guidelines - The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, (ODFW), “The guidelines are to assist under its authority to manage Oregon’s fish and wildlife resources has updated the following guidelines for timing of in-water work. The guidelines are to assist the the public in minimizing public in minimizing potential impacts to important fish, wildlife and habitat potential impacts...”. resources. Developing the Guidelines - The guidelines are based on ODFW district fish “The guidelines are based biologists’ recommendations. Primary considerations were given to important fish species including anadromous and other game fish and threatened, endangered, or on ODFW district fish sensitive species (coded list of species included in the guidelines). Time periods were biologists’ established to avoid the vulnerable life stages of these fish including migration, recommendations”. spawning and rearing. The preferred work period applies to the listed streams, unlisted upstream tributaries, and associated reservoirs and lakes. Using the Guidelines - These guidelines provide the public a way of planning in-water “These guidelines provide work during periods of time that would have the least impact on important fish, wildlife, and habitat resources. ODFW will use the guidelines as a basis for the public a way of planning commenting on planning and regulatory processes. There are some circumstances where in-water work during it may be appropriate to perform in-water work outside of the preferred work period periods of time that would indicated in the guidelines. ODFW, on a project by project basis, may consider variations in climate, location, and category of work that would allow more specific have the least impact on in-water work timing recommendations. -

Mckenzie River Sub-Basin Action Plan 2016-2026

McKenzie River Sub-basin Strategic Action Plan for Aquatic and Riparian Conservation and Restoration, 2016-2026 MCKENZIE WATERSHED COUNCIL AND PARTNERS June 2016 Photos by Freshwaters Illustrated MCKENZIE RIVER SUB-BASIN STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN June 2016 MCKENZIE RIVER SUB-BASIN STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The McKenzie Watershed Council thanks the many individuals and organizations who helped prepare this action plan. Partner organizations that contributed include U.S. Forest Service, Eugene Water & Electric Board, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, McKenzie River Trust, Upper Willamette Soil & Water Conservation District, Lane Council of Governments and Weyerhaeuser Company. Plan Development Team Johan Hogervorst, Willamette National Forest, U.S. Forest Service Kate Meyer, McKenzie River Ranger District, U.S. Forest Service Karl Morgenstern, Eugene Water & Electric Board Larry Six, McKenzie Watershed Council Nancy Toth, Eugene Water & Electric Board Jared Weybright, McKenzie Watershed Council Technical Advisory Group Brett Blundon, Bureau of Land Management – Eugene District Dave Downing, Upper Willamette Soil & Water Conservation District Bonnie Hammons, McKenzie River Ranger District, U.S. Forest Service Chad Helms, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jodi Lemmer, McKenzie River Trust Joe Moll, McKenzie River Trust Maryanne Reiter, Weyerhaeuser Company Kelly Reis, Springfield Office, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife David Richey, Lane Council of Governments Kirk Shimeall, Cascade Pacific Resource Conservation and Development Andy Talabere, Eugene Water & Electric Board Greg Taylor, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Jeff Ziller, Springfield Office, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife MCKENZIE RIVER SUB-BASIN STRATEGIC ACTION PLAN June 2016 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. -

History of the Siletz This Page Intentionally Left Blank for Printing Purposes

History of the Siletz This page intentionally left blank for printing purposes. History of the Siletz Historical Perspective The purpose of this section is to discuss the historic difficulties suffered by ancestors of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians (hereinafter Siletz Indians or Indians). It is also to promote understanding of the ongoing effects and circumstances under which the Siletz people struggle today. Since time immemorial, a diverse number of Indian tribes and bands peacefully inhabited what is now the western part of the State of Oregon. The Siletz Tribe includes approximately 30 of these tribes and bands.1 Our aboriginal land base consisted of 20 million acres located from the Columbia to the Klamath River and from the Cascade Range to the Pacific Ocean. The arrival of white settlers in the Oregon Government Hill – Siletz Indian Fair ca. 1917 Territory resulted in violations of the basic principles of constitutional law and federal policy. The 1787 Northwest Ordinance set the policy for treatment of Indian tribes on the frontier. It provided as follows: The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their land and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in the property, rights, and liberty, they never shall be invaded, or disturbed, unless in just, and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity shall from time to time be made for preventing wrongs being done to them, and for preserving peace, and friendship with them. 5 Data was collected from the Oregon 012.5 255075100 Geospatial Data Clearinghouse. -

Click Here to Download the 4Th Grade Curriculum

Copyright © 2014 The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. All rights reserved. All materials in this curriculum are copyrighted as designated. Any republication, retransmission, reproduction, or sale of all or part of this curriculum is prohibited. Introduction Welcome to the Grand Ronde Tribal History curriculum unit. We are thankful that you are taking the time to learn and teach this curriculum to your class. This unit has truly been a journey. It began as a pilot project in the fall of 2013 that was brought about by the need in Oregon schools for historically accurate and culturally relevant curriculum about Oregon Native Americans and as a response to countless requests from Oregon teachers for classroom- ready materials on Native Americans. The process of creating the curriculum was a Tribal wide effort. It involved the Tribe’s Education Department, Tribal Library, Land and Culture Department, Public Affairs, and other Tribal staff. The project would not have been possible without the support and direction of the Tribal Council. As the creation was taking place the Willamina School District agreed to serve as a partner in the project and allow their fourth grade teachers to pilot it during the 2013-2014 academic year. It was also piloted by one teacher from the Pleasant Hill School District. Once teachers began implementing the curriculum, feedback was received regarding the effectiveness of lesson delivery and revisions were made accordingly. The teachers allowed Tribal staff to visit during the lessons to observe how students responded to the curriculum design and worked after school to brainstorm new strategies for the lessons and provide insight from the classroom teacher perspective. -

South Fork of Little Butte Creek Area Naming Proposals

South Fork of Little Butte Creek Area Naming Proposals Presented by Dr. Alice G. Knotts INTRODUCTION We begin by thanking the Oregon Geographic Names Board for its careful work exhibited and accomplished in recent years for naming geographical features in the State of Oregon. We have identified some physical features in the area of the South Fork of Little Butte Creek located in Jackson County and put forth name suggestions and proposals. We believe that most of them are located on public lands of the U.S. Forest Service or the BLM, but the Knotts Cliff is on private land. 1 Naming Proposals for the South Fork of Little Butte Creek Area Identified in geographic order of approach from Medford, the road up the South Fork of Little Butte Creek and the Soda Springs trail 1009 that follows upstream Dead Indian Creek that is proposed to be named Latgawa Creek. 1. Hole-in-the-Rock Name a rock arch located on top of a hill NW of Poole Hill. Hole-in-the-Rock has been recorded on a BLM map but not with GNIS. 2. Pilgrim Cave Name a rock shelf with ancient campfire smoked walls. A shelter for travelers for thousands of years. 3. Knotts Bluff Name a cliff that defines the northern side of a canyon through which runs the S. Fork of Little Butte Creek. 4. Ross Point Name a prominent point on Knotts Cliff above the cave. 5. Latgawa Pinnacles Name a group of rocky pinnacles located near Camp Latgawa. 6. Marjorie Falls Name a water slide on Latgawa Creek upstream from the soda springs. -

Indian Country Welcome To

Travel Guide To OREGON Indian Country Welcome to OREGON Indian Country he members of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Ttribes and Travel Oregon invite you to explore our diverse cultures in what is today the state of Oregon. Hundreds of centuries before Lewis & Clark laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean, native peoples lived here – they explored; hunted, gathered and fished; passed along the ancestral ways and observed the ancient rites. The many tribes that once called this land home developed distinct lifestyles and traditions that were passed down generation to generation. Today these traditions are still practiced by our people, and visitors have a special opportunity to experience our unique cultures and distinct histories – a rare glimpse of ancient civilizations that have survived since the beginning of time. You’ll also discover that our rich heritage is being honored alongside new enterprises and technologies that will carry our people forward for centuries to come. The following pages highlight a few of the many attractions available on and around our tribal centers. We encourage you to visit our award-winning native museums and heritage centers and to experience our powwows and cultural events. (You can learn more about scheduled powwows at www.traveloregon.com/powwow.) We hope you’ll also take time to appreciate the natural wonders that make Oregon such an enchanting place to visit – the same mountains, coastline, rivers and valleys that have always provided for our people. Few places in the world offer such a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and culture within such a short drive. Many visitors may choose to visit all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes. -

Geology and Mineral Resources of Douglas County

STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES 1069 State Office Building Portland, Oregon 97201 BU LLE TIN 75 GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES of DOUGLAS COUNTY, OREGON Le n Ra mp Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries The preparation of this report was financially aided by a grant from Doug I as County GOVERNING BOARD R. W. deWeese, Portland, Chairman William E. Miller, Bend Donald G. McGregor, Grants Pass STATE GEOLOGIST R. E. Corcoran FOREWORD Douglas County has a history of mining operations extending back for more than 100 years. During this long time interval there is recorded produc tion of gold, silver, copper, lead, zinc, mercury, and nickel, plus lesser amounts of other metalliferous ores. The only nickel mine in the United States, owned by The Hanna Mining Co., is located on Nickel Mountain, approxi mately 20 miles south of Roseburg. The mine and smelter have operated con tinuously since 1954 and provide year-round employment for more than 500 people. Sand and gravel production keeps pace with the local construction needs. It is estimated that the total value of all raw minerals produced in Douglas County during 1972 will exceed $10, 000, 000 . This bulletin is the first in a series of reports to be published by the Department that will describe the general geology of each county in the State and provide basic information on mineral resources. It is particularly fitting that the first of the series should be Douglas County since it is one of the min eral leaders in the state and appears to have considerable potential for new discoveries during the coming years. -

Little Butte Creek Watershed Assessment

Little Butte Creek Watershed Assessment Little Butte Creek Watershed Council August 2003 Abstract The Little Butte Creek Watershed Assessment has been prepared for the Little Butte Creek Watershed Council with funding from the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board (OWEB). The Assessment was prepared using the guidelines set forth in the Governor’s Watershed Enhancement Board’s 1999 Oregon Watershed Assessment Manual. The purpose of this document is to assess the current conditions and trends of human caused and ecologic processes within the Little Butte Creek Watershed and compare them with historic conditions. Many important ecological processes within the watershed have been degraded over the last 150 years of human activity. This Assessment details those locations and processes that are in need of restoration as well as those that are operating as a healthy system. The Assessment was conducted primarily at the 5th field watershed level, that of the entire Little Butte Creek Watershed. List and describe field watershed levels below. Where possible, the analyses was refined to the smaller 6th field watershed level, thirteen of which exist within the Little Butte Creek Watershed. The assessment also notes gaps in data and lists recommendations for future research and data collection. It is intended that this document, and the Little Butte Creek Watershed Action Plan be used as guides for future research and watershed protection and enhancement over the next decade. The document was developed using existing data. No new data was collected for this project. Where data was lacking, it was detailed for future work and study. Acknowledgements This assessment was compiled and written by Steve Mason.