Setting up a Human Rights Film Festival

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Short Films Supports in Europe

e Un programme de l’Union européenne SHORT FILMS SUPPORTS IN EUROPE Belgium Bulgaria Croatia Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Ireland Italy Lithuania Netherlands Norway Poland Portugal Romania Spain Switzerland Published in 2013 MEDIA Desk France - 9 rue Ambroise Thomas - F-75009 Paris +33 1 47 27 12 77 - [email protected] - www.mediafrance.eu SHORT FILMS SUPPORTS IN… belgium Funding opportunities Centre du Cinéma or 50000 € for animated films. et de l’Audiovisuel (CCA) Foreign projects can be eligible if all the admissibility conditions are met. The maximum amount for those projects is 15000 €. Admissibility: independent pro- CSF (Film Selection Commis- duction company, registered in sion) – Short-length Films pro- Belgium. the whole support has duction and postproduction to be spent in Belgium. The di- GENERAL OVERVIEW support - made up of profes- rector has to be Belgian or Eu- Population: 10,9 million sionals, must issue an advice on ropean citizen (or resident in Languages: French, Dutch each admissible file submitted Belgium for 5 years). The direc- and German by the candidates. This advice tor’s nationality and country of Currency: Euro is then transmitted to the com- residence play a part in the dis- Number of theatres and petent Minister, who decides tinction between a national or a screens: 491 screens on granting or not the subsi- foreign project. (144 digital screens) / dies. For short-length films, the For foreign projects: All the 103 theatres committee meets 3 times a year. admissibility conditions above The members are spread over 2 must have been met. 30% of the Average admission colleges to examine the projects: financing has to be confirmed. -

Elise Piazza Weisenbach Unit 3 the Repressed And

Unit 3 The Repressed and the Repressors Introduction First we will kill all of the subversives; then…we will kill all of their sympathizers; then…those who remain undecided, and finally we will kill the indifferent ones. ~General Ibérico Saint-Jean, May 26, 1977 This quote by General Ibérico Saint-Jean attests to the clear and horrific plan of the junta’s Process of National Reorganization (El Proceso) to eliminate anyone considered an enemy of the state. In contrast to Saint-Jean’s clarity, the Argentines were left to wonder why people were arrested or disappeared. The media was not a reliable source of truthful information and people lived in fear of the government as well as their neighbors. In Unit 3, students will learn more about life in Argentina during this Dirty War from exiled writer Eduardo Galeano. They will learn about human rights organizations, and role-play a meeting with the OAS, government officials and prisoners. Essential Questions Lessons I-III • How does literature help us understand the human spirit? • How do writers express their most important sociopolitical views? • How does a writer’s style impact our understanding of sociopolitical events? • How can literature inspire social change? • How can we use databases to access information? • What is the role of human rights organizations? • How do human rights organizations engender change? Objectives Students will: • read and discuss literature by exiled writers • research human rights organizations • role-play a meeting with the OAS • read a science fiction comic strip Lesson I Century of the Wind Elise Piazza Weisenbach A. Materials a. -

Universidade Federal De Minas Gerais Escola De

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE MINAS GERAIS ESCOLA DE BELAS ARTES Eduardo Dias Fonseca A CONSTRUÇÃO DA NARRAÇÃO DO NACIONAL NO CINEMA BRASILEIRO E ARGENTINO (1995-2002) BELO HORIZONTE 2019 Eduardo Dias Fonseca A CONSTRUÇÃO DA NARRAÇÃO DO NACIONAL NO CINEMA BRASILEIRO E ARGENTINO (1995-2002) Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Artes da Escola de Belas Artes, da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, como requisito parcial à obtenção do título de Doutor em Artes. Linha de Pesquisa: Cinema Orientador: Prof. Dr. Evandro José Lemos da Cunha BELO HORIZONTE 2019 Ficha catalográfica (Biblioteca da Escola de Belas Artes da UFMG) Fonseca, Eduardo Dias, 1974- A construção da narração do nacional no cinema brasileiro e argentino (1995-2002) [manuscrito] / Eduardo Dias Fonseca. – 2019. 260 f. Orientador: Evandro José Lemos da Cunha. Tese (doutorado) – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Escola de Belas Artes. 1. Cinema brasileiro – Séc. XX-XXI – Teses. 2. Cinema argentino – – Teses. 3. Cinema – Aspectos sociais – Teses. 4. Cinema – Aspectos políticos – Teses. I. Cunha, Evandro, 1950-. II. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Escola de Belas Artes. III. Título. Dedico este trabalho a meu pai e minha mãe, dos quais a perda, nos últimos quatro anos, foi a mais sentida dentre todas as que eu tive. Os fragmentos, retalhos e restos da vida cotidiana devem ser repetidamente transformados nos signos de uma cultura nacional coerente, enquanto o próprio ato da performance narrativa interpela um círculo crescente de sujeitos nacionais. Na produção da nação como narração ocorre uma cisão entre a temporalidade continuísta, cumulativa, do pedagógico e a estratégia repetitiva, recorrente, do performático. -

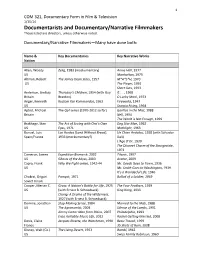

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

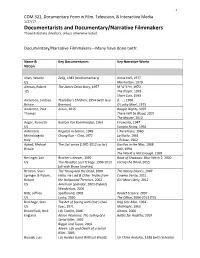

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Zagreb Winter 2016/2017

Maps Events Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Shopping Hotels Zagreb Winter 2016/2017 Trešnjevka Where wild cherries once grew Go Gourmet A Croatian feast Shopping Cheat Sheet Find your unique item N°86 - complimentary copy zagreb.inyourpocket.com Festive December Contents in Ljubljana ESSENTIAL CITY G UIDES Foreword 4 Sightseeing 46 A word of welcome Snap, camera, action Arrival & Getting Around 6 Zagreb Pulse 53 We unravel the A to Z of travel City people, city trends Zagreb Basics 12 Shopping 55 All the things you need to know about Zagreb Ready for a shopping spree Trešnjevka 13 Hotels 61 A city district with buzz The true meaning of “Do not disturb” Culture & Events 16 List of Small Features Let’s fill up that social calendar of yours Advent in Zagreb 24 Foodie’s Guide 34 Go Gourmet 26 Festive Lights Switch-on Event City Centre Shopping 59 Ćevap or tofu!? Both! 25. Nov. at 17:15 / Prešernov trg Winter’s Hot Shopping List 60 Restaurants 35 Maps & Index Festive Fair Breakfast, lunch or dinner? You pick... from 25. Nov. / Breg, Cankarjevo nabrežje, Prešernov in Kongresni trg Street Register 63 Coffee & Cakes 41 Transport Map 63 What a pleasure City Centre Map 64-65 St. Nicholas Procession City Map 66 5. Dec. at 17:00 / Krekov trg, Mestni trg, Prešernov trg Nightlife 43 Bop ‘till you drop Street Theatre 16. - 20. Dec. at 19:00 / Park Zvezda Traditional Christmas Concert 24. Dec. at 17:00 / in front of the Town Hall Grandpa Frost Proccesions 26. - 30. Dec. at 17:00 / Old Town New Year’s Eve Celebrations for Children 31. -

Nuevo Cine Argentino De Rapado a Historias Extraordinarias Veinticinco Años, Veinticinco Libros

Nuevo Cine Argentino De Rapado a Historias extraordinarias Veinticinco años, veinticinco libros El ciclo político inaugurado en Argentina a fines de 1983 se abrió bajo el auspicio de generosas promesas de justicia, renovación de la vida pública y ampliación de la ciudadanía, y conoció logros y retrocesos, fortalezas y desmayos, sobresaltos, obstáculos y reveses, en los más diversos planos, a lo largo de todos estos años. Que fue- ron años de fuertes transformaciones de los esquemas productivos y de la estructura social, de importantes cambios en la vida pública y privada, de desarrollo de nuevas formas de la vida colectiva, de actividad cultural y de consumo y también de expansión, hasta ni- veles nunca antes conocidos en nuestra historia, de la pobreza y la miseria. Hoy, veinticinco años después, nos ha parecido interesante el ejercicio de tratar de revisar estos resultados a través de la publica- ción de esta colección de veinticinco libros, escritos por académicos dedicados al estudio de diversos planos de la vida social argentina para un público amplio y no necesariamente experto. La misma tiene la pretensión de contribuir al conocimiento general de estos procesos y a la necesaria discusión colectiva sobre estos problemas. De este modo, dos instituciones públicas argentinas, la Biblioteca Nacional y la Universidad Nacional de General Sarmiento, a través de su Instituto del Desarrollo Humano, cumplen, nos parece, con su deber de contribuir con el fortalecimiento de los resortes cognos- citivos y conceptuales, argumentativos y polémicos, de la democra- cia conquistada hace un cuarto de siglo, y de la que los infortunios y los problemas de cada día nos revelan los déficits y los desafíos. -

Destination Croatia

© Lonely Planet Publications 16 Destination Croatia Sitting on a see-saw between the Balkans and Central Europe, Croatia has been suffering from something of a love-hate-love affair with the EU and its neighbours. Invited to join the UN Security Council in January 2008, its NATO membership was poised for 2009, but its dispute with the EU over its fishing laws saw displeased finger-wagging from the European officials and the already slightly elusive EU joining date (is it 2010? 2011? Perhaps 2012?) caught on yet another hurdle. March 2008 saw the beginning of the trial of Ante Gotovina, Croatia’s wartime general whose arrest was the main prerequisite for the beginning of Croatia’s talks for joining the EU back in 2005. Gotovina stands accused of ‘joint criminal enterprise’ for the expulsion of Serbs from Krajina in 1995. Revered and still seen as a hero by many in his native Zadar region, Gotovina’s trial is sure to bring home some controversial elements of Croatia’s Homeland War. Still in progress at the time of writing were the judicial reforms, the FAST FACTS struggle against corruption and the improvement of conditions for the Population: 4.5 million setting up of private businesses in the country, all of which have to be ful- Area: 56,538 sq km filled before Croatia can get its foot in the door of the desirable European club. Life for the average Croat remains on the tough side, however – the Head of state: President average salary of 6000KN per month is often too low to support a fam- Stjepan Mesić ily – and there is a declining but still substantial rate of unemployment GDP growth rate: 5% (11.18%). -

May 6–15, 2011 Festival Guide Vancouver Canada

DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL MAY 6–15, 2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE VANCOUVER CANADA www.doxafestival.ca facebook.com/DOXAfestival @doxafestival PRESENTING PARTNER ORDER TICKETS TODAY [PAGE 5] GET SERIOUSLY CREATIVE Considering a career in Art, Design or Media? At Emily Carr, our degree programs (BFA, BDes, MAA) merge critical theory with studio practice and link you to industry. You’ll gain the knowledge, tools and hands-on experience you need for a dynamic career in the creative sector. Already have a degree, looking to develop your skills or just want to experiment? Join us this summer for short courses and workshops for the public in visual art, design, media and professional development. Between May and August, Continuing Studies will off er over 180 skills-based courses, inspiring exhibits and special events for artists and designers at all levels. Registration opens March 31. SUMMER DESIGN INSTITUTE | June 18-25 SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEENS | July 4-29 Table of Contents Tickets and General Festival Info . 5 Special Programs . .15 The Documentary Media Society . 7 Festival Schedule . .42 Acknowledgements . 8 Don’t just stand there — get on the bus! Greetings from our Funders . .10 Essay by John Vaillant . 68. Welcome from DOXA . 11 NO! A Film of Sexual Politics — and Art Essay by Robin Morgan . 78 Awards . 13 Youth Programs . 14 SCREENINGS OPEning NigHT: Louder Than a Bomb . .17 Maria and I . 63. Closing NigHT: Cave of Forgotten Dreams . .21 The Market . .59 A Good Man . 33. My Perestroika . 73 Ahead of Time . 65. The National Parks Project . 31 Amnesty! When They Are All Free . -

Inhalt Content

Hauptförderung Förderung Supporters INHALT CONTENT 3 GRUSSWORT DES SENATORS FÜR KULTUR UND MEDIEN / WELCOME NOTE BY THE MINISTER OF CULTURE AND MEDIA 6 VORWORT DER FESTIVALLEITUNG / FESTIVAL DIRECTOR’S PREFACE 1 5 TRAILER Institutionelle Partnerschaften 1 7 WETTBEWERBE / COMPETITIONS 21 Jurys / Juries 27 Preise / Awards 29 Internationaler Wettbewerb / International Competition 47 Deutscher Wettbewerb / German Competition 59 Dreifacher Axel / Triple Axel 67 Mo&Friese Kinder Kurzfilm Festival / Create Converge Children’s Short Film Festival 85 LABOR DER GEGENWART / LABORATORY OF THE PRESENT 87 LAB 1 Gestimmtheiten – Das Kino und die Gesten Attunements – Cinema and Gestures 1 09 LAB 2 Afrotopia – In the Present Sense 1 24 LAB 3 Hamburger Positionen / Hamburg Positions 1 33 ARCHIV DER GEGENWART / ARCHIVE OF THE PRESENT 1 35 ARCHIV 1 CFMDC 1 42 ARCHIV 2 Vtape 1 51 OPEN SPACE Mo&Friese wird unterstützt von 1 59 WILD CARD 1 63 DISTRIBUTING 1 75 MORE HAPPENINGS 1 87 INDUSTRY EVENTS 1 97 ANIMATION DAY Medienpartnerschaften 209 KURZFILM AGENTUR HAMBURG 210 DANK / THANK YOU 212 REGISTER 222 BILDNACHWEISE / PICTURE CREDITS Mitgliedschaften 223 IMPRESSUM / IMPRINT 224 FESTIVALINFORMATION PROGRAMMPLAN / SCHEDULE U m s c h l a g / C o v e r 3 INTRO Grußwort des Kultur- senators der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg: Carsten Brosda Was hält uns als Gesellschaft zusammen? Und um- gekehrt: Was trennt uns voneinander? Der große Theater- mann Max Reinhardt benannte schon 1928 ein vermeint- liches Paradoxon, indem er sagte: »Wir können heute über den Ozean fliegen, hören und sehen, aber der Weg zu uns selbst und zu unserem Nächsten ist sternenweit.« Das ist noch heute nicht ganz von der Hand zu wei- sen – und beschreibt eine ständige Herausforderung: Denn ohne gegenseitiges Vertrauen und gegenseitige Unter- stützung ist gesellschaftlicher Zusammenhalt nichts weiter als eine schöne Idee. -

26 / 02 05 / 03 2017

Međunarodni festival dokumentarnog fi lma International Documentary Film Festival 26 / 02 05 / 03 2017 KAPTOL BOUTIQUE CINEMA CENTAR KAPTOL ZAGREB, CROATIA WWW.ZAGREBDOX.NET programska knjizica 2017 prijelom5.indd 1 14/02/17 08:50 KAPTOL BOUTIQUE CINEMA SADRŽAJ CENTAR KAPTOL Nova Ves 17, Zagreb ULAZNICE 4 RASPORED PROGRAMA 5 CENTAR KAPTOL NIVO 2 Službena konkurencija MEĐUNARODNA KONKURENCIJA 2 0 REGIONALNA KONKURENCIJA 2 6 NOVA VES Službeni program BIOGRAFSKI DOX 3 1 GLAZBENI GLOBUS 3 3 HAPPY DOX 3 5 KONTROVERZNI DOX 3 8 MAJSTORI DOXA 4 1 STANJE STVARI 4 3 3 TEEN DOX 4 6 ADU DOX 4 9 1 Retrospektive RETROSPEKTIVA NIKOLAUSA GEYRHALTERA 5 0 20 GODINA FACTUMA 5 1 2 Posebni programi MAJKE I KĆERI 5 3 65+ 5 4 5 5 TKALČIĆEVA ZAGREBDOXXL Posebna događanja 1 INFO POINT VIRTUAL REALITY 5 6 2 KAPTOL BOUTIQUE CINEMA 3 FESTIVALSKI CENTAR DOX PARTY 5 6 ZagrebDox Pro 5 7 programska knjizica 2017 prijelom5.indd 2 14/02/17 08:50 programska knjizica 2017 prijelom5.indd 3 14/02/17 08:50 Ulaznice DOX događanja Cijena ulaznice za projekcije u 15 i 16 sati iznosi 23 Premijere dokumentaraca iz Hrvatske i regije! kune. Dox događanja nastala su jer sve više autora iz Hrvatske i regije želi premijerno prikazati svoj film Cijena ulaznice za projekcije u 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 i 22 baš na ZagrebDoxu. Tako će u svečanom ozračju sata iznosi 28 kuna. Cineplexxa u Centru Kaptol biti prikazani najnoviji hrvatski i regionalni dokumentarci. Predstavit Cijena ulaznice za program The Best od Fest u ćemo njihove redatelje i potaknuti razgovor između nedjelju 05. -

Hedgehog's Home Festivals Awards Screenings

Hedgehog's Home / Jezeva kuca by Eva Cvijanovic 2017 / Canada, Croatia / 10' World premiere: 14/2/2017, Berlin International Film Festival Awards 1. Special Mention, Berlinale International Film Festival, Berlin, Germany (9/2-19/2/2017) 2. Best Film Award, KIKI International Film Festival for Kids, Zabok, Croatia (24/4-28/4/2017) 3. First prize in MIDI SENIOR category, VAFI International Children and Youth Animation Festival, Varazdin, Croatia (30/5-4/6/2017) 4. Audience Award, Animafest – World Festival of Animated Film, Zagreb, Croatia (5/6-10/6/2017) 5. Special Jury Award, Animafest – World Festival of Animated Film, Zagreb, Croatia (5/6- 10/6/2017) 6. Best Animation Award, Kratki na brzinu – Revue of Croatian Short Films, Sv. Ivan Zelina, Croatia (6/6-11/6/2017) 7. Audience Award, Mediterranean Film Festival Split, Split, Croatia (8/6-17/6/2017) 8. Special Mention, Mediterranean Film Festival Split, Split, Croatia (8/6-17/6/2017) 9. Young Audience Award, Annecy International Animation Festival, Annecy, France (12/6- 17/6/2017) 10. Oktavijan Award for the Best Animated Film, Days of Croatian Film, Zagreb, Croatia (16/6- 21/6/2017) 11. Best Music Award, Days of Croatian Film, Zagreb, Croatia (16/6-21/6/2017) 12. Audience Award, Days of Croatian Film, Zagreb, Croatia (16/6-21/6/2017) 13. Grand Prix in Short Animated Film Category, Supertoon International Animation Festival, Sibenik, Croatia (16/7-21/7/2017) 14. Grand Prix in Short Animated Film Category, Kinder Film Fest Kyoto, Kyoto, Japan (3/8-5/8/2017) 15. Special Mention, Guanajuato International Film Festival, Guanajuato, Mexico (21/7-30/7/2017) 16.