Copyright by Matthew James Barnard 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hard Men of Welsh Rugby Free

FREE THE HARD MEN OF WELSH RUGBY PDF Lynn Davies | 144 pages | 31 Dec 2011 | Y Lolfa Cyf | 9781847713520 | English | Talybont, United Kingdom History of rugby union in Wales - Wikipedia Steve Morris 1 September — 29 May was a Welsh international rugby union flanker who played club rugby for Cross Keys. A hard man, Morris was extremely physical in the way he played the game, sometimes over physical and he was unafraid to The Hard Men of Welsh Rugby to violence if it was warranted. It is reported that he once knocked out a Welsh heavyweight boxing champion in a sparring session. A The Hard Men of Welsh Rugby miner by profession, Morris would work down the pit at Risca Colliery on a Saturday morning and then turn out to play for Cross Keys in the afternoon. Morris spent his entire playing career at Cross Keys and later became the club's chairman. On his death his ashes were scattered at Pandy Park, the team's home ground. Morris began playing rugby before the outbreak of World War I and continued playing when he could as a recruit in the British Army. Morris made his international debut against England inthe first Cross Keys player to represent his country. In the game against France inMorris played alongside his Cross Keys team mate, Fred Reevesmade all the more special as the two of them were also co-workers at the Risca Colliery. Morris's aggression was used to good effect in other games; when in against an overly violent French team he and Swansea's Tom Parker were called upon to fight back to subdue their opponents. -

Wru Copy Master

WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL 2005-2006 UNDEB RYGBI CYMRU CYF 125 YEARS OF RUGBY EXCELLENCE Whatever it takes WRU staff - delivering key objectives in the interests of our game WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT 2005-2006 Contents Officials of the WRU Chairman’s View 5-9 Patron 125 Years and Counting 10 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Principal Sub-Committees WRU Chief Executive’s View 11 Honorary Life Vice-Patron The Right Honourable Sir Tasker Watkins VC, GBE, DL Finance Committee Financial Report 13-15 Martin Davies (Chairman), David Pickering, Kenneth Hewitt, President David Moffett (resigned 31 December 2005), Humphrey Evans, Group Commercial Report 16 Keith Rowlands Steve Lewis, John Jones, Alan Hamer (resigned 30 June 2006) Group Compliance Report 17 Board Members of Welsh Rugby Union Ltd. Regulatory Committee David Pickering Chairman Russell Howell (Chairman), Mal Beynon, Geraint Edwards, The Professional Game 19-27 Kenneth Hewitt Vice-Chairman Brian Fowler, John Owen, Ray Wilton, Aurwel Morgan High Performance Rugby 29-33 David Moffett Group Chief Executive (resigned 31 December 2005) Mal Beynon Game Policy Committee Refereeing Report 35 Gerald Davies CBE, DL Alan Jones (Chairman), Roy Giddings, Gethin Jenkins, Gerald Davies CBE DL, Martin Davies David Matthews, Mostyn Richards, Peredur Jenkins, Community Rugby 37-42 Geraint Edwards Anthony John, Steve Lewis, Mike Farley, Rolph James Obituaries 43-45 Humphrey Evans International Rugby Board Representatives Brian Fowler David Pickering, Kenneth Hewitt Accounts 46-66 Roy Giddings Russell Howell Six Nations Committee Representatives Gethin Jenkins David Pickering, Martin Davies Peredur Jenkins ERC Representatives Welsh Rugby Union Ltd Anthony John Steve Lewis, Stuart Gallacher (Regional Representative) Alan Jones 1st Floor, Golate House John Jones Celtic Rugby Representatives 101 St. -

Park Promotion Pontypool Rugby Club

Neutral Citation Number: [2012] EWHC 1919 (QB) Case No: HQ12X01661 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 11 July 2012 Before : SIR RAYMOND JACK SITTING AS A JUDGE OF THE HIGH COURT - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : PARK PROMOTION LIMITED T/A Claimant PONTYPOOL RUGBY FOOTBALL CLUB - and - THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED Defendant - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Ian Rogers (instructed by Messrs Geldards LLP) for the Claimants Adam Lewis QC and Tom Mountford (instructed by Messrs Charles Russell LLP) for the Defendants Hearing dates: 25, 26 and 27 June 2012 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Judgment Sir Raymond Jack : 1. This case is concerned with the right of the claimant, the Pontypool Rugby Club, a club with a proud history, to continue to play in the Premier Division of Welsh rugby in the 2012/13 season. The defendant is the Welsh Rugby Union, which organises and controls the sport of rugby union in Wales. It is the view of the WRU that as a result of the re-organisation of the Premier Division to reduce the number of clubs playing in it and Pontypool’s position in order of playing meritocracy of the fourteen clubs formerly in the division, the club is now only eligible to play in the Championship, the next division down. The essence of Pontypool’s case is that clubs which are above it on a basis of playing merit have not met the requirements to hold an A licence as required for the Premiership by the WRU’s National League Rules 2011/2012, and so there is a place for Pontypool within the Premiership. -

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football

Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland and Michael Rowe Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Also by Jon Garland THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with D. Malcolm and Michael Rowe) Also by Michael Rowe THE FUTURE OF FOOTBALL: Challenges for the Twenty-First Century (co-editor with Jon Garland and D. Malcolm) THE RACIALISATION OF DISORDER IN TWENTIETH CENTURY BRITAIN Racism and Anti-Racism in Football Jon Garland Research Fellow University of Leicester and Michael Rowe Lecturer in Policing University of Leicester © Jon Garland and Michael Rowe 2001 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2001 by PALGRAVE Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE is the new global academic imprint of St. Martin’s Press LLC Scholarly and Reference Division and Palgrave Publishers Ltd (formerly Macmillan Press Ltd). -

Rugby League As a Televised Product in the United States of America

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications, College Journalism and Mass Communications of 7-31-2020 Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America Mike Morris University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, Communication Technology and New Media Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Morris, Mike, "Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America" (2020). Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/journalismprojects/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journalism and Mass Communications, College of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Professional Projects from the College of Journalism and Mass Communications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Rugby League as a Televised Product in the United States of America By Mike Morris Abstract Rugby league is a form of rugby that is more similar to American football than its more globally popular cousin rugby union. This similarity to the United States of America’s most popular sport, that country’s appetite for sport, and its previous acceptance of foreign sports products makes rugby league an attractive product for American media outlets to present and promote. Rugby league’s history as a working-class sport in England and Australia will appeal to American consumers hungry for grit and authenticity from their favorite athletes and teams. -

Histofina DIVING

HistoFINA DIVING MEDALLISTS AND STATISTICS Last updated on September 2019 Copyright FINA, Lausanne 2019 In memory of Jean-Louis Meuret 1 CONTENT 1. Introduction 4 2. Olympic Games 5 • NF with Olympic victories 7 • NF on Olympic podiums 3. World Championships 8 4. Diving World Cups 10 5. Diving World Series 12 6. Diving Grand Prix 14 7. Men’s Diving 17 • Olympic podiums o Men’s Olympic medallists by nationality 19 o The best at Oympic Games 23 • World Championships 25 o Men’s World medallists by nationality 27 o The best at World Championships 31 • Men’s Olympic & World medallists by nationality 33 o The best at Olympic Games & World Championships 41 • Diving World Cups 42 o Men’s World Cup medallists by nationality 45 o The best at Diving World Cup 49 • Men’s Olympic, World & World Cup medallists by nationality 51 o The best at OG, World Championships & World Cup 59 • Diving World Series 61 • Diving Grand Prix 63 o Diving Grand Prix Super Finals (up to 2006) 65 8. Women’s Diving 66 • Olympic podiums o Women’s Olympic medallists by nationality 68 o The best at Oympic Games 71 • World Championships 73 o Women’s World medallists by nationality 76 o The best at World Championships 80 • Women’s Olympic & World medallists by nationality 82 2 o The best at Olympic Games & World Championships 88 • Diving World Cups 89 o Women’s World Cup medallists by nationality 91 o The best at Diving World Cup 95 • Women’s Olympic, World & World Cup medallists by nationality 97 o The best at OG, World Championships & World Cup 104 • Diving World Series 105 • Diving Grand Prix 107 o Diving Grand Prix Super Finals (up to 2006) 109 9. -

As Lecturers Strike

13 JANUARY 1989 OMING 50OI,il L THE LEEDS STUDENT COMIC RELIEF T BASH INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER Mk. II! Watch for details! INSIDE THIS CAMS 111 WEEK: NEWS: AS LECTURERS STRIKE CRIMEW AYE niversity lecturers have students delivered to voted to boycott all work University departments HITS LEEDS connected with exams, in was criticized for being 'too narrow,' concen- pursuit of their pay claim for 1988. trating too much on the STUDENTS The AUT's action is designed to issue of decreasing AUT combat the falling real and salaries, and not enough p3 relative earnings of university on the general underfun- 8.481.9S °I. ding of Higher Education. lecturers. The meeting heard a The union claims report from John Char- The man that to compensate PAUL HARTLEY tres, AUT Vice President who broke for inflation over the and member of the na- two years to April tional negotiating team. into Leeds 1988 they would re- reports He outlined the origins of quire around 9% and the decision to boycott Uni's that 15% would be exams, hold examiners' the examination process. meetings, or announce He also announced that computer needed to match results. the AUT were in- relative pay in- Work done as part of vestigating the possibility ••••••••• p3 creases within com- continual assesment and of setting up a welfare parable professions. research degrees will be fund for AU"I' members LOANWATCH The result of the ballot exempt from any im- whose pay had been calling for industrial ac- mediate ban, although docked as a result of the 1...••••••• ... pS tion was announced on students will not be given dispute. -

Catapult Signs League-Wide Agreement with the Welsh Rugby Union

ASX Market Announcement 3 April 2017 Catapult signs league-wide agreement with the Welsh Rugby Union Catapult Group International Limited (ASX: CAT) today announced it has signed an agreement for a minimum four-year term with the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU), under which Catapult will provide the WRU with tracking units for high performance purposes. Under the agreement, the WRU will acquire a total of 318 tracking units covering nine teams including international and regional (Cardiff Blues, Newport Gwent Dragons, Ospreys and Scarlets) sides. Each team, through the WRU’s high performance pathway, will use Catapult’s market leading analytics platform for all training and game-day sessions to help drive enhanced physical performance in elite rugby union in Wales. Commenting on the agreement with Catapult, WRU CEO Martyn Phillips, said: “The WRU is delighted to extend the use of Catapult tracking units within our high-performance pathway. We have nine teams across our regions and at international level which will be supported with the latest technology from Catapult.” The agreement will also explore live match-day tracking using Catapult’s latest stadia technology – ClearSkyII. For select games the WRU may explore opportunities for broadcast partners to use live metrics supported by Catapult. Karl Hogan, Global Head of League & Data Partnerships for Catapult commented: “The WRU is a great example of an elite sport governing body that is forward thinking and innovative. That makes them a great partner for Catapult to work with in both driving increased athletic performance and also exploring opportunities to showcase the broadcast capabilities of our technology – especially Clearsky. -

The Welsh Rugby Union Limited Annual Report 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 ADRODDIAD BLYNYDDOL Dewrder | Hiwmor | Cywirdeb | Rhagoriaeth | Teulu | Llwyddiant Courage | Humour | Integrity | Excellence | Family | Success 2 THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED – ANNUAL REPORT 2020 THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED ANNUAL REPORT AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 President’s Message .......................................................................................................................................4 Chairman’s Statement ................................................................................................................................... 8 Group Chief Executive’s Summary ...............................................................................................................10 Strategic Report ...........................................................................................................................................16 A Year in Community Rugby ........................................................................................................................28 Return to Rugby ...........................................................................................................................................38 A Year in Professional Rugby ........................................................................................................................42 Return to Rugby ...........................................................................................................................................52 -

Issued Decision UK Anti-Doping and Daniel Matthews

Issued Decision UK Anti-Doping and Daniel Matthews Disciplinary Proceedings under the Anti-Doping Rules of the Welsh Rugby Union. This is an Issued Decision made by UK Anti-Doping Limited (‘UKAD’) pursuant to the Welsh Rugby Union (‘WRU’) Anti-Doping Rules (the ‘ADR’). It concerns a violation of the ADR committed by Mr Daniel Matthews and records the applicable Consequences. Capitalised terms used in this Decision shall have the meaning given to them in the ADR unless otherwise indicated. Background and Facts 1. The WRU is the governing body for the sport of rugby union in Wales. UKAD is the National Anti-Doping Organisation for the United Kingdom. The WRU has adopted the UK Anti-Doping Rules as its own Anti-Doping Rules (the ‘ADR’). 2. Mr Matthews is a 30-year-old rugby union player (29-years-old as at the date of his Anti-Doping Rule Violation) for Bargoed Rugby Football Club. At all material times in this matter Mr Matthews was subject to the jurisdiction of the WRU and bound to comply with the ADR. Pursuant to the ADR, UKAD has results management responsibility in respect of all players subject to the jurisdiction of the WRU. 3. On 24 March 2018, UKAD collected a urine Sample from Mr Matthews in accordance with WADA’s International Standard for Testing and Investigations (‘ISTI’) In-Competition after the WRU Principality Premiership match between Cross Keys RFC and Bargoed RFC at Pandy Park, Crosskeys, Newport, NP11 7BS. Mr Matthews was an unused substitute. 4. Assisted by the Doping Control Officer, Mr Matthews split the urine Sample into two separate bottles (an ‘A Sample’ and a ‘B Sample’). -

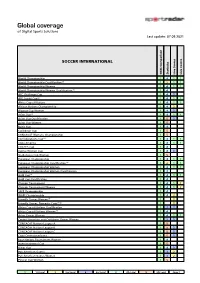

Sportradar Coverage List

Global coverage of Digital Sports Solutions Last update: 07.09.2021 SOCCER INTERNATIONAL Odds Comparison Statistics Live Scores Live Centre World Championship 1 4 1 1 World Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 World Championship Women 1 4 1 1 World Championship Women Qualification (1) 1 4 AFC Challenge Cup 1 4 3 AFF Suzuki Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Africa Cup of Nations 1 4 1 1 African Nations Championship 1 4 2 Algarve Cup Women 1 4 3 Asian Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Asian Cup Qualification 1 5 3 Asian Cup Women 1 5 Baltic Cup 1 4 Caribbean Cup 1 5 CONCACAF Womens Championship 1 5 Confederations Cup (1) 1 4 1 1 Copa America 1 4 1 1 COSAFA Cup 1 4 Cyprus Women Cup 1 4 3 SheBelieves Cup Women 1 5 European Championship 1 4 1 1 European Championship Qualification (1) 1 2 1 1 European Championship Women 1 4 1 1 European Championship Women Qualification 1 4 Gold Cup (6) 1 4 1 1 Gold Cup Qualification 1 4 Olympic Tournament 1 4 1 2 Olympic Tournament Women 1 4 1 2 SAFF Championship 1 4 WAFF Championship 1 4 2 Friendly Games Women (1) 1 2 Friendly Games, Domestic Cups (1) (2) 1 2 Africa Cup of Nations Qualification 1 3 3 Africa Cup of Nations Women (1) 1 4 Asian Games Women 1 4 1 1 Central American and Caribbean Games Women 1 3 3 CONCACAF Nations League A 1 5 CONCACAF Nations League B 1 5 3 CONCACAF Nations League C 1 5 3 Copa Centroamericana 1 5 3 Four Nations Tournament Women 1 4 Intercontinental Cup 1 5 Kings Cup 1 4 3 Pan American Games 1 3 2 Pan American Games Women 1 3 2 Pinatar Cup Women 1 5 1 1st Level 2 2nd Level 3 3rd Level 4 4th Level 5 5th Level Page: -

The Welsh Rugby Union Limited Annual Report 2017

2 THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED – ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE 4 CHAIRMAN’S STATEMENT 6 GROUP CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S SUMMARY 8 STRATEGIC REPORT 14 REPORT FROM THE HEAD OF RUGBY PARTICIPATION 22 REPORT FROM THE HEAD OF RUGBY PERFORMANCE 26 REPORT FROM THE HEAD OF RUGBY OPERATIONS 32 REPORT FROM THE NATIONAL HEAD COACH 34 DIRECTORS’ REPORT 36 CONSOLIDATED INCOME STATEMENT 40 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 41 CONSOLIDATED AND COMPANY BALANCE SHEETS 42 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 43 COMPANY STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 44 CONSOLIDATED STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 45 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 46 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT 64 WELSH RUGBY UNION GOVERNANCE 67 REGISTERED OFFICE 69 BOARD OF DIRECTORS 70 EXECUTIVE BOARD 77 OBITUARIES 82 COMMERCIAL PARTNERS 86 THE WELSH RUGBY UNION LIMITED – ANNUAL REPORT 2017 3 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Dennis Gethin The past year has seen some truly outstanding moments on the international rugby field and I feel privileged, as WRU President, to say I was there for many of them. Wales began the season in style, winning three of our four Under Armour Series internationals - our best result for a similar series since 2002 - and all credit to Rob Howley and his coaching team who so ably deputised for Warren Gatland whilst he was away on British & Irish Lions duty. We ended the season in style too, with a victorious summer tour, playing Tonga in Auckland followed by a first visit to Apia, Samoa, under The game against Samoa was rugby club flags lining the stands. the leadership of Robin McBryde.