Clearance Decision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report

AB InBev annual report 2018 AB InBev - 2018 Annual Report 2018 Annual Report Shaping the future. 3 Bringing People Together for a Better World. We are building a company to last, brewing beer and building brands that will continue to bring people together for the next 100 years and beyond. Who is AB InBev? We have a passion for beer. We are constantly Dreaming big is in our DNA innovating for our Brewing the world’s most loved consumers beers, building iconic brands and Our consumer is the boss. As a creating meaningful experiences consumer-centric company, we are what energize and are relentlessly committed to inspire us. We empower innovation and exploring new our people to push the products and opportunities to boundaries of what is excite our consumers around possible. Through hard the world. work and the strength of our teams, we can achieve anything for our consumers, our people and our communities. Beer is the original social network With centuries of brewing history, we have seen countless new friendships, connections and experiences built on a shared love of beer. We connect with consumers through culturally relevant movements and the passion points of music, sports and entertainment. 8/10 Our portfolio now offers more 8 out of the 10 most than 500 brands and eight of the top 10 most valuable beer brands valuable beer brands worldwide, according to BrandZ™. worldwide according to BrandZTM. We want every experience with beer to be a positive one We work with communities, experts and industry peers to contribute to reducing the harmful use of alcohol and help ensure that consumers are empowered to make smart choices. -

Landmark Literature

JANUARY 2018 # 60 Upfront In My View Feature Business Monitoring big cat diets Catching the next wave Tracking down counterfeit PolyLC’s Andrew Alpert – by a whisker in IMS drugs with Minilab shares his lessons learned 13 18 34 – 43 44 – 48 Landmark Literature Ten experts select and reflect on standout papers that advanced analytical science in 2017. 22 – 33 www.theanalyticalscientist.com NORTH AMERICA SPP speed. USLC® resolution. A new species of column. • Drastically faster analysis times. • Substantially improved resolution. • Increased sample throughput with existing instrumentation. • Dependable reproducibility. Choose Raptor™ SPP LC columns for all of your valued assays to experience Selectivity Accelerated. www.restek.com/raptor www.restek.com/raptor Pure Chromatography Image of the Month Core Values Researchers at Scripps Institution of Oceanography have developed a new way to measure the average temperature of the world’s oceans over geological time. The scientists used a dual-inlet isotope ratio mass spectrometer to measure noble gases trapped in Antarctic ice caps, and showed that mean global ocean temperature increased by 2.57 ± 0.24 degrees Celsius over the last glacial transition (20,000 to 10,000 years ago). Seen here is an ice core from West Antarctica, drilled in 2012. Credit: Jay Johnson/IDDO. Reference: B Bereiter et al., “Mean global ocean temperatures during the last glacial transition”, Nature, 553, 39–44 (2018). Would you like your photo featured in Image of the Month? Send it to [email protected] -

2008 Bjcp Style Guidelines

2008 BJCP STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP) Style Guidelines for Beer, Mead and Cider 2008 Revision of the 2004 Guidelines Copyright © 2008, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. See our website www.bjcp.org for updates to these guidelines. 2003-2004 BJCP Beer Style Committee: Gordon Strong, Chairman Ron Bach Peter Garofalo Michael L. Hall Dave Houseman Mark Tumarkin 2008 Contributors: Jamil Zainasheff, Kristen England, Stan Hieronymus, Tom Fitzpatrick, George DePiro 2003-2004 Contributors: Jeff Sparrow, Alan McKay, Steve Hamburg, Roger Deschner, Ben Jankowski, Jeff Renner, Randy Mosher, Phil Sides, Jr., Dick Dunn, Joel Plutchak, A.J. Zanyk, Joe Workman, Dave Sapsis, Ed Westemeier, Ken Schramm 1998-1999 Beer Style Committee: Bruce Brode, Steve Casselman, Tim Dawson, Peter Garofalo, Bryan Gros, Bob Hall, David Houseman, Al Korzonas, Martin Lodahl, Craig Pepin, Bob Rogers 48 i ilSot...................................................17 Stout rial Impe Russian 13F. Sot..............................................................17 Stout American 13E. pdate.................................46 U 2008 T, CHAR STYLE BJCP 2004 tra Stout........................................................16 tra Ex Foreign 13D. N/A N/A N/A 5-12% 0.995-1.020 1.045-100 Perry or Cider Specialty Other D. y Cider/Perry...........................................45 y Specialt Other 28D. tu ................................................................16 Stout l Oatmea 13C. ine......................................................................44 Applew 28C. tu ....................................................................15 Stout Sweet 13B. N/A N/A N/A 9-12% 0.995-1.010 1.070-100 Wine Apple C. ie .....................................................................44 Cider Fruit 28B. 3.DySot.......................................................................15 Stout Dry 13A. N/A N/A N/A 5-9% 0.995-1.010 1.045-70 Cider Fruit B. -

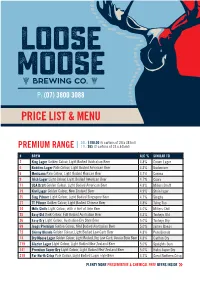

P: (07) 3800 3088 Price List & Menu

P: (07) 3800 3088 PRICE LIST & MENU 50L: $180.00 (6 cartons of 24 x 345ml) PREMIUM RANGE | 17L: $65 (2 cartons of 24 x 345ml) # BREW ALC % SIMILAR TO 2 King Lager Golden Colour, Light Bodied Australian Beer 4.8% Crown Lager 4 Buddies Lager Pale Colour, Light Bodied American Beer 4.3% Budweiser 6 Mexicana Pale Colour, Light Bodied Mexican Beer 4.7% Corona 9 Irish Lager Light Colour, Light Bodied American Beer 4.7% Coors 11 USA Draft Golden Colour, Light Bodied American Beer 4.8% Millers Draft 19 Kiwi Lager Golden Colour, New Zealand Beer 4.9% Stein lager 25 Sing Pilsner Light Colour, Light Bodied Singapore Beer 4.7% Singha 27 TT Pilsner Golden Colour, Light Bodied Chinese Beer 4.8% Tsing Tao 34 Mills Chills Light Colour, with a hint of lime Beer 4.0% Millers Chill 35 Easy Old Dark Colour, Full Bodied Australian Beer 4.3% Tooheys Old 36 Easy Dry Light Colour, Australian Dry Style Beer 5.0% Tooheys Dry 69 Joags Premium Golden Colour, Med Bodied Australian Beer 5.0% James Boags 72 Skinny Blonde Golden Colour, Light Bodied Low Carb Beer 4.8% Pure Blonde 73 Dry Moose Lager Golden Colour, Light Bodied, Dry, Low Carb, Aussie Style Beer 4.8% Carlton Dry 119 Glazier Lager Light Colour, Light Bodied New Zealand Beer 5.0% Speights Sum 141 Premium Super Dry Light Colour, Light Bodied New Zealand Beer 5.0% Hahn Super Dry 219 Far North Crisp Pale Colour, Light Bodied Lager style Beer 4.2% Great Northern Crisp PLENTY MORE PRESERVATIVE & CHEMICAL FREE BEERS INSIDE » 50L: $210.00 (6 cartons of 24 x 345ml) EXCLUSIVE RANGE | 17L: $75 (2cartons of 24 x 345ml) -

Class-Action Lawsuit

Case 1:16-cv-21181-UU Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 04/01/2016 Page 1 of 51 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA Case No. __________________ DR. HENRY VAZQUEZ, on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated, CLASS ACTION JURY DEMAND Plaintiff, v. ANHEUSER-BUSCH COMPANIES, LLC, Defendant. ___________________________________/ CLASS ACTION COMPLAINT Plaintiff, DR. HENRY VAZQUEZ, on behalf of himself and all others similarly situated (the “Class” or “Class Members”), hereby brings this action against ANHEUSER-BUSCH COMPANIES, LLC (“AB”) for its sale of alleged “Abbey” Beer that, quite simply, isn’t. Plaintiff states and alleges as follows: NATURE OF CLAIM 1. This class action is brought on behalf of Plaintiff and all other similarly situated individuals who purchased Leffe Beer1, and were deceived by AB’s labeling and packaging into believing that Leffe Beer is brewed in an abbey, and thereby brewed in smaller quantities under the supervision of monks. The packaging and labeling on Leffe Beers include the words “Abbey Ale” and “Abbaye de Abbey of Leffe,” a picture of an abbey, and the “Story of the abbey of Leffe.” 1 As used herein, the terms “Leffe Beer” refers to six-pack bottles of Leffe Brown and Leffe Blond. 1 Case 1:16-cv-21181-UU Document 1 Entered on FLSD Docket 04/01/2016 Page 2 of 51 Further, the labels state “Anno 1240,” implying that Leffe Beer has been brewed since that date in an abbey. 2. Through its marketing, AB bolsters its deceptive labeling and packaging by making misleading claims, including the following: . -

Wine - Glass & Bottle R L B

WINE - GLASS & BOTTLE R L B Mitchelton VS Cuvee Mitchelton 6.5 24 De Bortoli King Valley Prosecco King Valley 7.5 30 Clancy Cabernet Blend Barossa 7 11 26 St Hallet Rose Grenache Barossa 8 13 32 Sister’s Run Bethlehem Block Cabernet Sauvignon Barossa 7.5 12 30 Morgans Bay Chardonnay SE Australia 6.5 10 24 Hentley Farm Poppy Field Blend Chardonnay Dominant Barossa 7.5 12 30 Brown Brothers Moscato King Valley 7.5 12 30 Mandoletto Pinot Grigio Italy 7.5 12 30 Ara Single Estate Pinot Noir Marlborough, New Zealand 7.5 12 30 Oyster Bay Sauvignon Blanc New Zealand 8 13 32 Morgans Bay Sauvignon Blanc SE Australia 6.5 10 24 Wongary Shiraz Wrattonbully (Coonawarra) 7 11 26 Sister’s Run Epiphany Shiraz McLaren Vale 7.5 12 30 WINE - BOTTLE Taltarni T Series NV Multi Regional 27 Yarra Burn Sparkling Victoria 34 Brown Brothers Prosecco 200ml Piccolo King Valley 9.5 Yellowglen 200ml Piccolo SE Australia 9 Henkell Dealcoholised 200ml Piccolo Rhine Valley, Germany 7.5 Sam Miranda Ballerina Bianco Blend King Valley 30 Sister’s Run St Petri’s Riesling Eden Valley 27 Ara Single Estate Sauvignon Blanc Marlborough 30 Run Riot Sauvignon Blanc New Zealand 32 Shaw & Smith Sauvignon Blanc New Zealand 40 Taltarni T Series Sauvignon Blanc Pyrenees 27 Preece Pinot Grigio Mitchelton 30 Wongary Pinot Gris Wrattonbully (Coonawarra) 26 Knappstein Beaumont Chardonnay Barossa 27 Sister’s Run Sunday Slippers Chardonnay Barossa 30 Paul Conti Chardonnay Margaret River 32 Sam Miranda Ballerina Moscato King Valley 30 WINE - BOTTLE Bertaine Rose France 32 Sam Miranda Ballerina -

Pavilion Restaurant

Pavilion Restaurant WINE LIST PRICE ($) SPARKLING Glass Bottle TRENTHAM ESTATE NV BRUT | Trentham Cliffs, NSW ...................................................................N/A 7.5 (200ml) A delicate, light weight wine with persistent green apple and citrus flavours on a soft creamy palate. SAN MARTINO NV PROSECCO DOC Extra Dry | Veneto, Italy ........................................................6.5 24.5 A thread of sweetness, excellent fruit and clean, balance acidity. WHITE XANADU DJL SAUVIGNON BLANC SEMILLON | Margaret River, WA ................................................7 28.5 Blend of Sauvignon Blanc and Semillon is a crisp, refreshing style offering zesty citrus, herbs and passionfruit characters. Pa ROAD SAUVIGNON BLANC | Marlborough, NZ ..........................................................................6 21.5 2nd label of te Pa, classically Marlborough in style and flavour of citrus, tropical fruit and snow pea characters. TALISMAN RIESLING | Geographe, WA ..........................................................................................7 28.5 A light, dry and crisp wine with punchy aroma of rose petal, citrus blossom and lime, strong varietal flavour. ROSILY VINEYARD CHARDONNAY | Margaret River, WA .................................................................7.5 32.5 A classic stone fruit and white peach flavours as well as some mineral and flinty elements. RIVER RETREAT PINK MOSCATO | Trentham Cliffs, NSW ...............................................................5.5 15 Slightly fizzy with -

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a -

Introducing the Bushmills 4.5L Bottle

THE OFFICIAL VOICE OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND FEDERATION OF CLUBS Club ReviewVOLUME 32 - Issue 1, 2019 INTRODUCING THE BUSHMILLS 4.5L BOTTLE Due to popular demand, local favourite Bushmills Irish Whiskey is now available in a 4.5L bottle. With hints of honey, malt and spice a Bushmills Original Hot Whiskey is the perfect pour this season. Available now through all good wholesalers Optics and POS available while stocks last Contact Patrick Morgan: [email protected] +447734128048 Bushmills & Associated logos are trademarks® of “The Old Bushmills Distillery”, Bushmills, County Antrim. ©2019 Proximo Spirits. ENJOY BUSHMILLS RESPONSIBLY 050 Black bush Jan 2019 press ad A4 V5.indd 1 09/02/2019 15:24 Federation Update Minutes of the Executive Meeting Hosted by Philip Russell Limited, on Wednesday 9th January 2019 The Federation Executive in the UK have made remain unchanged, in that, in passed as a true record by Tommy Committee received a warm representation in respect to this all cases, the first port of call McMinn and Jim Hanna. welcome to the offices of Philip license, in view of which we are should be the club insurers, Russell Limited, by Michael happy for them to take the lead which, if your club insurance is The next Executive Committee Barnes, General Manager, and in this matter. with Rollins Club Insurance, meeting will be hosted by the Rhonda Simpson, Sales Manager. should be ‘DAS’. Our Federation Felons Club, Belfast. Details The Secretary provided details colleague Joe Patterson, who of the Federation AGM, to be Prior to commencing the of a meeting with a supplier in has experience in this field, is hosted by the RAOB Club In Philip Russell Limited has been supplying the licensed trade for over 40 years and within this time have meeting, the Chairman, John the annual process of renewing keen to underline this advice. -

Beer Knowledge – for the Love of Beer Section 1

Beer Knowledge – For the Love of Beer Beer Knowledge – For the Love of Beer Contents Section 1 - History of beer ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Section 2 – The Brewing Process ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Section 3 – Beer Styles .................................................................................................................................................... 14 Section 4 - Beer Tasting & Food Matching ...................................................................................................................... 19 Section 5 – Serving & Selling Beer .................................................................................................................................. 22 Section 6 - Cider .............................................................................................................................................................. 25 Section 1 - History of beer What is beer? - Simply put, beer is fermented; hop flavoured malt sugared, liquid. It is the staple product of nearly every pub, club, restaurant, hotel and many hospitality and tourism outlets. Beer is very versatile and comes in a variety of packs; cans, bottles and kegs. It is loved by people all over the world and this world wide affection has created some interesting styles that resonate within all countries -

The Best Beer Company in a Better World

In November 2008 we closed the combination with Anheuser-Busch, creating Anheuser-Busch InBev, a world class consumer goods company with a pro- forma EBITDA of approximately 8.2 billion euro in 2008. The combined business has four of the top ten selling beers in the world, and has a number one or number two position in over 20 markets. Our dream is to become Anheuser-Busch InBev Anheuser-Busch The Best Beer Company in a Better World Annual Report 2008 Annual Report 2008 Report Annual Anheuser-Busch InBev In November 2008 we closed the combination with Anheuser-Busch, creating Anheuser-Busch InBev, a world class consumer goods company with a pro- forma EBITDA of approximately 8.2 billion euro in 2008. The combined business has four of the top ten selling beers in the world, and has a number one or number two position in over 20 markets. Our dream is to become Anheuser-Busch InBev Anheuser-Busch The Best Beer Company in a Better World Annual Report 2008 Annual Report 2008 Report Annual Anheuser-Busch InBev 4 | Letter to Shareholders 6 | Anheuser-Busch: The story so far 8 | The Language we speak 14 | The Brands that define us 22 | The Zones that drive us 30 | The People that make the difference 34 | The World around us 41 | Financial Report 127 | Corporate Governance ‘Anheuser-Busch and InBev both have rich brewing traditions and a commitment to quality and integrity. We will succeed by celebrating Anheuser-Busch InBev is a publicly traded and integrating both company (Euronext: ABI) based in Leuven, companies’ strong brands, Belgium. -

Anheuser-Busch Inbev SA/NV (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended 31 December 2018 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report Commission File No.: 001-37911 Anheuser-Busch InBev SA/NV (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) Belgium (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Brouwerijplein 1, 3000 Leuven, Belgium (Address of principal executive offices) John Blood General Counsel and Company Secretary Brouwerijplein 1, 3000 Leuven Belgium Telephone No.: + 32 16 27 61 11 Email: [email protected] (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Ordinary shares without nominal value New York Stock Exchange* American Depositary Shares, each representing one ordinary share New York Stock Exchange without nominal value 6.375% Notes due 2040 (issued January 2010) New York Stock Exchange 5.375% Notes due 2020 (issued January 2010) New York Stock Exchange