Theory in Anthropology Since the Sixties Author(S): Sherry B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: an Introduction to Harris Brian D

The Behavior Analyst 2007, 30, 37–47 No. 1 (Spring) Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: An Introduction to Harris Brian D. Kangas University of Florida The year 2007 marks the 80th anniversary of the birth of Marvin Harris (1927–2001). Although relations between Harris’ cultural materialism and Skinner’s radical behaviorism have been promulgated by several in the behavior-analytic community (e.g., Glenn, 1988; Malagodi & Jackson, 1989; Vargas, 1985), Harris himself never published an exclusive and comprehensive work on the relations between the two epistemologies. However, on May 23rd, 1986, he gave an invited address on this topic at the 12th annual conference of the Association for Behavior Analysis in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, entitled Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions. What follows is the publication of a transcribed audio recording of the invited address that Harris gave to Sigrid Glenn shortly after the conference. The identity of the scribe is unknown, but it has been printed as it was written, with the addendum of embedded references where appropriate. It is offered both as what should prove to be a useful asset for the students of behavior who are interested in the studyofcultural contingencies, practices, and epistemologies, and in commemoration of this 80th anniversary. Key words: cultural materialism, radical behaviorism, behavior analysis Cultural Materialism and Behavior Analysis: Common Problems and Radical Solutions Marvin Harris University of Florida Cultural materialism is a research in rejection of mind as a cause of paradigm which shares many episte- individual human behavior, radical mological and theoretical principles behaviorism is not radically behav- with radical behaviorism. -

Symbols and Rituals: an Interpretive Approach to Faith- Based Behavior

SYMBOLS AND RITUALS: AN INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO FAITH- BASED BEHAVIOR By: James A. Forte Presented at: NACSW Convention 2014 November, 2014 Annapolis, Maryland | www.nacsw.org | [email protected] | 888-426-4712 | Symbols and Rituals: An Interpretive Approach to Faith-Based Behavior Presentation at National Association of Christian Social Workers, Annual Conference Annapolis, Maryland November 8, 2014 James A. Forte Professor, Salisbury University Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Memorable Words “The phrase ‘nothing is a practical as good theory’ is a twist of an older truth: Nothing improves theory more than its confrontation with practice” (Hans Zetterberg, 1962, page 189). Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Overview: Framework for Making Sense of Geertz’s Theory Models – Exemplary root theorists Metaphors – Theory’s root metaphors Mapping – Theoretical elements and relations, Translation to eco-map Method - Directives for further inquiry & theory use Middle-range Theory-based applications (Inquiry theorizing and planned change) Marks of Critical thinking about theory Excellence Symbols and Rituals (Geertz and Faith Behavior) Clifford Geertz and The Symbolic Anthropology Approach This approach to religion and spirituality provides an analysis of the system of meanings embodied in the symbols and expressed in rituals which make up the religion or spiritual system (for a focal social group), and the relating of these systems to social-structural and psychological processes (Geertz, 1973, page 125). Symbols -

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA

Qualia NICHOLAS HARKNESS Harvard University, USA Qualia (singular, quale) are cultural emergents that manifest phenomenally as sensuous features or qualities. The anthropological challenge presented by qualia is to theorize elements of experience that are semiotically generated but apperceived as non-signs. Qualia are not reducible to a psychology of individual perceptions of sensory data, to a cultural ontology of “materiality,” or to philosophical intuitions about the subjective properties of consciousness. The analytical solution to the challenge of qualia is to con- sider tone in relation to the familiar linguistic anthropological categories of token and type. This solution has been made methodologically practical by conceptualizing qualia, in Peircean terms, as “facts of firstness” or firstness “under its form of secondness.” Inthephilosophyofmind,theterm“qualia”hasbeenusedtodescribetheineffable, intrinsic, private, and directly or immediately apprehensible experiences of “the way things seem,” which have been taken to constitute the atomic subjective properties of consciousness. This concept was challenged in an influential paper by Daniel Dennett, who argued that qualia “is a philosophers’ term which fosters nothing but confusion, and refers in the end to no properties or features at all” (Dennett 1988, 387). Dennett concluded, correctly, that these diverse elements of feeling, made sensuously present atvariouslevelsofattention,wereactuallyidiosyncraticresponsestoapperceptions of “public, relational” qualities. Qualia were, in effect, -

Symbolic Anthropology Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920

Symbolic Anthropology • Examines symbols & processes by which humans assign meaning. • Addresses fundamental Symbolic anthropology questions about human social life, especially through myth & ritual. ANTH 348/Ideas of Culture • Culture does not exist apart from individuals. • It is found in interpretations of events & things around them. Symbolic Anthropology Victor Turner (1920-1983) • Studied with Max Gluckman @ Manchester University. • Culture is a system of meaning deciphered by • Taught at: interpreting key symbols & rituals. • Stanford University • Anthropology is an interpretive not scientific • Cornell University • University of Chicago endeavor . • University of Virginia. • 2 dominant trends in symbolic anthropology • Publications include: • Schism & Continuity in an African Society (1957) represented by work of British anthropologist • The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual (1967) Victor Turner & American anthropologist • The Drums of Affliction: A Study of Religious Processes Among the Ndembu of Zambia Clifford Geertz. (1968) • The Ritual Process: Structure & Anti-Structure (1969). • Dramas, Fields, & Metaphors (1974) • Revelation & Divination in Ndembu Ritual (1975) Social Drama Social drama • • Early work on village-level social processes among the For Turner, social dramas have four main phases: Ndembu people of Zambia 1. Breach –rupture in social relations. examination of demographics & economics. 2. Crisis – cannot be handled by normal strategies. • Later shift to analysis of ritual & symbolism. 3. Redressive action – seeks to remedy the initial problem, • Turner introduced idea of social drama redress and re-establish • "public episodes of tensional irruption*” 4. Reintegration or schism – return to status quo or an • “units of aharmonic or disharmonic process, arising in conflict situations.” alteration in social arrangements. • They represent windows into social organization & values . -

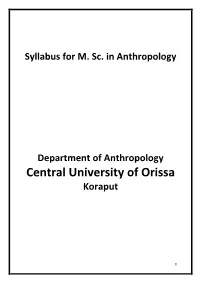

M.Sc. in Anthropology Syllabus

Syllabus for M. Sc. in Anthropology Department of Anthropology Central University of Orissa Koraput 0 M.Sc. in ANTHROPOLOGY Semester-I: Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No. 1 ANT – C 311 Biological Anthropology -I 4 100 2 ANT – C 312 Socio-Cultural Anthropology 4 100 3 ANT – C 313 Archaeological Anthropology 4 100 & Museology 4 ANT – C 314 Research Methods 4 100 5 ANT – C 315 Tribes in India 2 100 6 ANT – C 316 General Practical – I 2 100 Semester-II: Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No. 7 ANT – C 321 Biological Anthropology -II 4 100 8 ANT – C 322 Theories of Society and 4 100 Culture 9 ANT – C 323 Pre- and Proto- History of 4 100 India, Africa and Europe 10 ANT – C 324 Indian Anthropology 4 100 11 ANT – C 325 Peasants in India 2 100 12 ANT – C 326 General Practical – II 2 100 1 Semester-III: (GROUP – A: Physical / Biological Anthropology) Course Course Code Title Credits Full No. Mark 13 ANT – C 331 Anthropological Demography 4 100 14 ANT – C 332 Field Work Training 2 100 15 ANT – C 333 Human Ecology: Biological & Cultural 2 100 dimensions 16 ANT – C 334 ‘A’ Medical Genetics 4 100 17 ANT – C 335 ‘A’ Practical in Biological Anthropology - I 4 100 18 ANT – E1 336 ‘A’ Growth and Nutrition, OR 4 100 ANT – E2 336 ‘A’ Forensic Anthropology – I, OR ANT – E3 336 ‘A’ Environmental Anthropology Students can choose one Extra Electives offered by Department and one Allied Electives from other Subjects in 3rd Semester Semester-III: (GROUP – B: Socio - Cultural Anthropology) Course Course Code Title Credits Full Mark No. -

What's in a Meme?

What’s in a Meme? The Development of the Meme as a Unit of Culture Garry Chick The Pennsylvania State University University Park, Pennsylvania, USA Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association as part of the session, “Perceiving Culture: Unit Definition in Cultural Anthropology,” November 21, 1999. Please do not quote without permission. An earlier version of this paper is in press in Social Science Today (in Russian). Abstract Over the past 150 years numerous labels have been applied to the “parts” of culture. Some of these, including “themes,” “configurations,” “complexes,” and “patterns” are macro level. Micro level terms include “ideas,” “beliefs,” “values,” “rules,” “principles,” “symbols,” “concepts,” and a few others. The macro level labels often appear to be particular arrangements of micro level units. But which of these, if any, is the (or, an) operational unit of cultural transmission, diffusion, and evolution? Recently proposed units of cultural transmission typically derive from analogies made between cultural and biological evolution. Even though the unit of selection in biological evolution (i.e., the gene, the individual, or the group) is still under debate, the “meme,” originally suggested by Dawkins (1976) as a cultural analog of the gene, has been “selected” by many as a viable unit of culture. A “science of memes” (“memetics”) has been proposed (Lynch 1996) and numerous web sites devoted to the meme exist on the internet. This paper will trace the development of the meme and, in the process, critically address its utility as a unit of culture. 2 The whole history of science shows that advance depends upon going beyond “common sense” to abstractions that reveal unobvious relations and common properties of isolatable aspects of phenomena. -

Language in Society: an Introduction to Linguistic & Semiotic Anthropology

LANGUAGE IN SOCIETY: AN INTRODUCTION TO LINGUISTIC & SEMIOTIC ANTHROPOLOGY Reed College Fall 2006 Linguistics 313 Steve Hibbard Tu/Th 18:10‐19:30 Eliot 409 Vollum xxx x7489 Office Hours: Tuesday 3:00‐4:30 Thursday 4:00‐5:30 [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This advanced undergraduate course explores the central topics in linguistic (or semiotic) anthropology. We will begin with a close study of the theoretical ʺtools of the trade,ʺ including, most centrally, Saussurian structuralist linguistics and Peircean semiotics. The remainder of the semester is arranged thematically: each week, we will examine a major topic of linguistic and/or semiotic anthropological concern, giving theoretical, methodological, and empirical work‐‐ both ʺclassicʺ and contemporary‐‐(roughly) equal time. From “The Construction of Personhood,” and “Learning to be Gendered,” to “The Question of ‘Linguistic Relativity’,” and “Language, Madness, and Schizophrenia,” we will approach each weekly topic from the distinctive theoretical perspective developed in the first part of the semester. Students are responsible for writing a short, weekly reaction paper, to be handed in before each week’s final class. Reaction papers might be one page, or five pages—it depends on you and your level of interest in the week’s reading. Important: these are not meant to be literature reviews; rather, you may think (in writing) about one or more of the focus questions, or, otherwise, consider any (relevant) topic that moves you, excites you, bothers, confuses, distracts, annoys, or otherwise touches you. Students should, at a minimum, be prepared to discuss each of that class period’s focus questions in conference. -

Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big

AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST Linguistic Anthropology Linguistic Anthropology in 2013: Super-New-Big Angela Reyes ABSTRACT In this essay, I discuss how linguistic anthropological scholarship in 2013 has been increasingly con- fronted by the concepts of “superdiversity,” “new media,” and “big data.” As the “super-new-big” purports to identify a contemporary moment in which we are witnessing unprecedented change, I interrogate the degree to which these concepts rely on assumptions about “reality” as natural state versus ideological production. I consider how the super-new-big invites us to scrutinize various reconceptualizations of diversity (is it super?), media (is it new?), and data (is it big?), leaving us to inevitably contemplate each concept’s implicitly invoked opposite: “regular diversity,” “old media,” and “small data.” In the section on “diversity,” I explore linguistic anthropological scholarship that examines how notions of difference continue to be entangled in projects of the nation-state, the market economy, and social inequality. In the sections on “media” and “data,” I consider how questions about what constitutes lin- guistic anthropological data and methodology are being raised and addressed by research that analyzes new and old technologies, ethnographic material, semiotic forms, scale, and ontology. I conclude by questioning the extent to which it is the super-new-big itself or the contemplation about the super-new-big that produces perceived change in the world. [linguistic anthropology, superdiversity, new media, big data, -

Skeeling 1.Pdf

Musicking Tradition in Place: Participation, Values, and Banks in Bamiléké Territory by Simon Robert Jo-Keeling A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor Judith T. Irvine, Chair Emeritus Professor Judith O. Becker Professor Bruce Mannheim Associate Professor Kelly M. Askew © Simon Robert Jo-Keeling, 2011 acknowledgements Most of all, my thanks go to those residents of Cameroon who assisted with or parti- cipated in my research, especially Theophile Ematchoua, Theophile Issola Missé, Moise Kamndjo, Valerie Kamta, Majolie Kwamu Wandji, Josiane Mbakob, Georges Ngandjou, Antoine Ngoyou Tchouta, Francois Nkwilang, Epiphanie Nya, Basil, Brenda, Elizabeth, Julienne, Majolie, Moise, Pierre, Raisa, Rita, Tresor, Yonga, Le Comité d’Etudes et de la Production des Oeuvres Mèdûmbà and the real-life Association de Benskin and Associa- tion de Mangambeu. Most of all Cameroonians, I thank Emanuel Kamadjou, Alain Kamtchoua, Jules Tankeu and Elise, and Joseph Wansi Eyoumbi. I am grateful to the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for fund- ing my field work. For support, guidance, inspiration, encouragement, and mentoring, I thank the mem- bers of my dissertation committee, Kelly Askew, Judith Becker, Judith Irvine, and Bruce Mannheim. The three members from the anthropology department supported me the whole way through my graduate training. I am especially grateful to my superb advisor, Judith Irvine, who worked very closely and skillfully with me, particularly during field work and writing up. Other people affiliated with the department of anthropology at the University of Michigan were especially helpful or supportive in a variety of ways. -

The Transformation of Cultural Anthropology : the Decline of Ecology and Structure and the Rise of Political Economy and the Cultural Construction of Social Reality*

The Transformation of Cultural Anthropology : The Decline of Ecology and Structure and the Rise of Political Economy and the Cultural Construction of Social Reality* William P. MITCHELL" Deux principales approches dominent la recherche anthropologique actuelle aux Etats-Unis : l'économie politique et la construction cultu relle de l'« autre », motifs qui ont largement remplacé les analyses éco logiques et strucluralo-symboliques proposées il y a encore dix ans. Cet article rend compte de ces développements dans l'ethnographie des Andes de ces vingt-cinq dernières années. Dans les Andes, pendant les années 1970 et 1980, de nombreux cher cheurs ont étudié l'écosystème vertical, stimulés par l'hypothèse de l'ar chipel vertical de John Murra et l'écologie culturelle de Julián Steward et Marvin Harris. L'hypothèse de Murra et le fort zeitgeist écologique des années 1970 ont orienté la recherche andine pendant plus de deux This is a slightly revised version of a talk presented to the Five Field Update panel of the Society for Anthropology in Community Colleges at the 91st Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, San Francisco, CA, November, 1992. I am grateful to the Monmouth University Grants and Sabbaticals Committee for supporting various aspects of my research. Barbara Jaye read several drafts of the paper and has provided me many helpful suggestions. I am grateful to Monica Barnes, Jane Freed, Sean Mitchell, Barbara Price and Glenn Stone for their comments on the paper. I also thank Constance Sutton and Sean Mitchell for demonstrating to me the utility of incorporating identity and construction into issues of class and power. -

Claude Lévi-Strauss at His Centennial: Toward a Future Anthropology Albert Doja

Claude Lévi-Strauss at his Centennial: toward a future anthropology Albert Doja To cite this version: Albert Doja. Claude Lévi-Strauss at his Centennial: toward a future anthropology. Theory, Culture and Society, SAGE Publications, 2008, 25 (7-8), pp.321-340. 10.1177/0263276408097810. halshs- 00405936 HAL Id: halshs-00405936 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00405936 Submitted on 5 Oct 2009 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. 321-340 097810 Doja (D) 1/12/08 11:52 Page 321 Published in: "Theory, Culture & Society", vol. 25 (7-8), 2008, pp. 321–340 Claude Lévi-Strauss at His Centennial Toward a Future Anthropology Albert Doja Abstract Lévi-Strauss’s centennial is an opportunity to show his inextricable connec- tions with the evolution of 20th-century thought and what these promise for 21st-century anthropology. He has mapped the philosophical parameters for a renewed ethnography which opens innovative approaches to history, agency, culture and society. The anthropological understanding of history, for instance, is enriched by methodical application of his mytho-logical analysis, in particular his claim that myths are ‘machines for the suppression of time’. -

Chapter 2 Style

Chapter 2 Style "Every apparition can be experienced in two ways. The two ways are not at random, but they are attached to the apparitions – they are derived from the nature of the apparition, from two of their characteristics: exterior – interior.” Wassily Kandinsky1 “Le style c’est l’homme même.” Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon2 Although people find it difficult to define the concept of style spontaneously, they classify each other as belonging or not belonging together by respective styles. They always do so when they see others as punk, nerd, hipster, hippie, yuppie, emo, or belonging to hip hop or the mainstream. Which succeeds more fre- quently than not! Yet, the question is how this works and why. Sociology asserts style to be either representative or constitutive of social groups, or else both.3 However, there is consensus in all of sociology that social 1 Kandinsky 1973 (1926), p. 13, my translation. 2 Cited after Saisselin 1958. 3 Modernist sociology regards differences in endowment (financial and cultural capital) as being constitutive for forming social groups; style is merely representative of social groups (for exam- ple, the Birmingham School in its analysis of British youth cultures [Hebdige 1988]). In contrast, in the postmodern variant of sociology, the group style is understood as the constituent charac- teristic of the group; it is only by showing a style, that groups can come into being and are able to persist; other socio-cultural characteristics, for example the endowment with capital, play no or only a secondary role. Bourdieu (1982) marks the transition from modernism to postmodernism, 48 Part 1: Culture of Dissimiarity groups and their style form an inseparable entity.