A Comparison of Preschoole~S 1 Verbal And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dail Question About Cappoquin Man's Detention in Tenerite Noel N

Dunpanactr) MARIO'S MOTOR FACTORS HORNIBROOKS MARY ST., DUNGARVAN LI3MO"E Spares for- Dungarvan Ceader COOKERS, KETTLES, FRIDGES ^mr and SOUTHERN DEMOCRAT TWIN TUBS, AUTOMATICS, FOR VACUUM CLEANERS AND Circulating throughout the County and City of Waterford, South Tipperary and South-East Cork TUMBLE DRYERC TEL. 058/42417, anytime Vol. 50. No. 2561. FRIDAY, APRIL 29, 1988. REGISTERED AT THE GENERAL PRICE firir VAT> POST OFFICE AS A NEWSPAPER 1zo'J V'nt, VH I ) TOYOTA Dail Question About Cappoquin Man's Former Minister for Agricul- ture, Deputy Austin Deasy. Dun- that he has been victimised by garvan, has given notice that the Spanish authorities in being he intends to ask the Minister kept In prison for the past three for Foreign Affairs in a Dail months as he was only an inno- Question whether he will inves- Detention In Tenerite cent bystander at the time the HOMELESS YOUNG ing rough, others were squatting tigate the circumstances sur- row broke out In the pub PEOPLE while many were staying tem- Calling on the Irish and Brit- rounding the detention of Kevin Mr. O'Connor has been in de- ther the Minister would use his porarily with friends or in sor. of Mr. and Mrs. John A which had been refused, but ish governments to secure bet- A new Research Report on O'Connor. Cappoquin an Irish tention for over two months good offices to ensure an early O'Connor. Carrlgeen, Capoo- was under appeal by defence flats but unable to cope or in National, in Tenerife. The ques- ter protection for young people Youth Homelessness in Ireland without trial and has been re- trial or that bail is granted, quin. -

Newsletter 11/08 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 11/08 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 231 - Juni 2008 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 11/08 (Nr. 231) Juni 2008 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, Ob es nun um aktuelle Kinofilme, um nen Jahr eröffnet und gelangte vor ein liebe Filmfreunde! besuchte Filmfestivals oder gar um paar Wochen sogar ganz regulär in die Die schlechte Nachricht gleich vorweg: einen nostalgischen Blick zurück auf deutschen Kinos. Wer den Film dort unsere Versandkostenpauschale für die liebgewonnene LaserDisc geht – verpasst hat oder ihn (verständlicher- Standard-Pakete erhöht sich zum 01. die angehende Journalistin weiß, wo- weise) einfach noch einmal sehen Juli 2008. Ein gewöhnliches Paket ko- von sie schreibt. Kennengelernt haben möchte, der kann die US-DVD des Ti- stet dann EUR 6,- (bisher: EUR 4,-), wir Anna während ihres Besuchs beim tels ab September in seine Film- eine Nachnahmesenduung erhöht sich 1. Widescreen-Weekend in der Karlsru- sammlung integrieren. Der Termin für auf EUR 13,- (bisher: EUR 9,50). Diese her Schauburg. Ein Wort ergab das eine deutsche Veröffentlichung wurde Preiserhöhung ist leider notwendig andere – und schon war die junge Frau zwar noch nicht bekanntgegeben, doch geworden, da unser Vertriebspartner Feuer und Flamme, für den Laser wird OUTSOURCED mit Sicherheit DHL die Transportkosten zum 01. Juli Hotline Newsletter zu schreiben. Wir auch noch in diesem Jahr in Deutsch- 2008 anheben wird. -

The Original Tory

Leeds Student 2241 1 1999 Volume 29: Issue No.19 THE ORIGINAL TORY BOY Exclusive interview with Conservative leader and proud Yorkshireman William Hague • PAGES 11-13 COUNCIL PROVING THAT CRIME CAN PAY TO DUMP STORE PLANS inquiry backs move to keep sports fields CAMPAIGNERS are By KEVIN against the development and celebrating a public inquiry's staged demonstrations outside decision not to build a plan would "harm the character Leeds Town Hall. Student shopping centre on the Leeds and appearance of a prominent activist Natasha De Vere University Iiodington playing open area." commented: "This is a huge fields. Council planners are success for student Leeds City Council had refusing to comment on the campaigners and local residents submitted plans with the inquiry's decision until the who have fought these plans. university to build a retail park full report is released on March despite the combined strength on the Weetwood site as part 22. However they are likely of the university and the Labour of the Leeds Unitary to accept most of the report's City Council." Development Plan. recommendations. Harold Best. Leeds North But an inspector this week Over 1.000 students and West MR believes its a big urged that the Bodington Fields residents signed a petition PAGE TWO, COLUMN ONE DOING YOUR BIT FOR COMIC RELIEF • PACE SIX MATHS THE WAY TO DO IT - COUNTING THE COST OF CLEVER CALCULATORS ON PAGE SEVEN 2 NEWS Leeds Student, Friday March 12 1999 Archaeologists dig up a new theory Film crew box LONG-held assumptions By NAVEED RAJA about the short length of time that people from problem, belie ■c. -

Police Appeal for Witnesses to Horrific Collision IT's a BOOTIE CALL!

Leeds Student www.leedsdotstudent.co.uk October. 2,1998 Volume 29: Issue No.2 Deadly duo Mark and Lard on why tribute bands rule FINALIST IT'S A BOOTIE CALL! CRITICAL AFTER ACCIDENT Police appeal for witnesses to horrific collision A FINALIST is on the critical the accident. the second to By KEVIN PMMAN list after being involved in a occur on Woodhouse Lane in serious road accident outside at 10:20 on Saturday night. a week. Leeds University. John was taken to Leeds A spokesman said: "We are John Reeve, a 21-year-old General Infirmary where he is looking into new road safety Fuel and Energy student, was in a critical but stable condition initiatives in the light of what struck down on the pedestrian in the neurology unit. has happened. In the meantime. crossing as he walked towards His mother said: -It's a we are advising all students to the cash machines opposite crucial stage at the moment take care when crossing roads the Parkinson building. regarding his injuries and we in the busy areas of Leeds." He was hit by a green are hoping that he can pull Witnesses to the accident Mercedes Benz 380 as it was through." should contact Millgarth police IN THE RED: Hyde Park patron with new footwear Pic: Dail Thubron travelling towards Headingley Police are still investigating on 0113 241 3059. THE LATEST CHAPTER IN THE HIGHER EDUCATION FUNDING CRISIS - PAGE 5 OF LEEDS 2 NEWS Leeds Student, Friday October 2 1998 Boffins keen to lower alarming reaction times SC1F.NTISTS who helped RV MATT WIRER develop a new style alarm for emergency vehicles have difficult to locate the source. -

Jail Report Misses Escape Angle

fa Standardized Snnny, quite warm today. FINAL Clear and cool tonight. Fair, pleasant tomorrow and Snn- i Long Branch EDITION Monmonth County's Home Newspaper for 92 Years M».BA]NK,NJ. FRIDAY, JUNE 4*1971 Jail Report Misses Escape Angle : 3y WILLIAM J.ZAORSKI jail escape but it was reported' pards interfering with his at- vestigator miss the point that tion of the cell block. There misrepresentation of the coun- individual cells where they Sheriff Paul Klernan had FREEHOLD - Architects to have been about the es- tempts. It goes into detail of the officer was in the 'guards are two doors preventing ty jail of which people of Mon- are also fed and handled on a reported that jail guard Mar- ' for the county jail and county cape. alleged security defects of corridor' which means the in- them access to the guard's mouth County can be proud." one-to-one basis by guards. vin Jackson was caned into i freeholders said yesterday The 25-page report pre- areas where inmates should mates were out of the cell corridor.) . ,•'.'• Mr. Keuper later said that The two inmates'who es- the maximum security celBV \ that a report of the county jail pared by county Investigators not be permitted unless under area. ; . , Freeholder Director Joseph .Mr. Rast was a trained crimi- caped during the evening of lock on the xuse that an Uh j by county detectives "missed Frederick Rast ana Bruce guard. "This is a new version of C. Irwin called the Hast re- nal investigator. "Admittedly April 5, Daniel Brewer of Nep- mate was ill. -

Sanibel — Captiva

SANIBEL — CAPTIVA Serving the Islands since 1961 Vol. 16, No. 28 Tuesday, July 20, 1976 1 section — 10 cents 'Hie long awaited final adoption of the proposed comprehensive land use plan (CLUP) for the City of Sanibel came late yesterday afternoon at a public hearing held in Sanibel City Hall, making July 19 a red letter day in the history of the young city. The plan had originally been slated for adoption on June 29, until a new state law governing zoning changes forced the city council to delay action on the CLUP for two additional weeks. The plan could therefore have been , adopted on July 13, last Tuesday, for which purpose the council held a special public hearing at City Hall beginning at 5:01 p.m. At that meeting, the council heard 15 speakers address the plan before deciding to withhold Bill Roberts, looking a lot less tired, at one of the first presentations last year action on the document for sic more days to give all interested parties the restrictive with respect to the rights of necessary public services to ac- Prior to yesterday's meeting, there opportunity to review and respond to had been some talk around City Hall of developers and property owners. comodate the rapid growth that the revisions made in the CLUP in special One such group, the Concerned putting the plan up for a general workshop sessions prior to that time. Property Owners of Sanibel, has taken Island has experienced since the referendum vote in the upcoming At yesterday's meeting, the council a public stand in opposition to the plan November election, but, according to moved unanimously to enact the plan and has already begun accepting construction of the Sanibel Causeway city officials, the idea was discarded into law, after hearing a final bout of contributions to help defray the cost of in the early 1960's. -

Coincidence, Or Confiscation?

SAN! BEL — CAPTIVA Serving the Islands since 1961 Vol. 16, No. 22 Tuesday, June 8, 1976 2 sections — ] 0 cents densi Coincidence, # # or Confiscation? Conserve! Ion —Planning recommended 'acquisitions1 IANIBEI WETLANDS <£t ~]J.N. "Ding" Darling O.tJ 'Nat'l. Wildlife Refuge ,. I Freshwater Wetlands Preserve ^Proposed Freshwater LilWetiands Acquisition Area The above maps, as you can see, ove. np with what is either a remarkable in question, the question of "coincidence" may indeed be most pertinent. In coincidence or may rather indicate that the plan was pre-planned as long the story which follows are quotes from the 1973-74 correspondence ... ago as 1973. The green overlay indicates the Plan's .05 (need 20 acres for one dwelling Since the recent Palo Alto, California, court decision, in which the federal unit,) circuit court ruled that the Palo Alto city fathers could not "re-zone" property The ISLANDER leaves it to you to decide ... we draw no editorial con- they wanted to preserve for the public, but must indeed purchase the land clusions ... just raise the question. On February 22,1974, a letter was sent to agencies. However, the Florida Department Earl Starns, director of the division of State of Natural Resources was able to negotiate Planning signed by Vernon MaeKenzie, then successfully the purchase of, only 43 acres of Corps holds president of the Sanibel-Captiva Planning about 82 acres of Sanibel wetlands for which Board, and Richard Workman, Adm. $260,650 in Federal grant funds had been Director of the Sanibel-Captiva Con- made available, with the result that $120,000 Captiva groin hearing servation Foundation. -

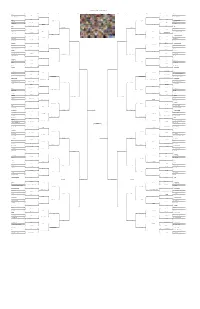

Favorite-TV-Themes-Elite-Eight-Results Large

FAVORITE TV THEMES - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Cheers 49 48 MASH Cheers 21 44 MASH Car 54, Where Are You? 7 7 The Wild Wild West The Muppet Show 39 30 MASH The Muppet Show 54 40 The Jeffersons The Muppet Show 37 13 The Jeffersons Coach 3 8 Curb Your Enthusiasm The Muppet Show 46 44 Happy Days Sesame Street 47 48 Happy Days Sesame Street 43 31 Happy Days The Wonder Years 10 5 Matlock Sesame Street 23 31 Happy Days The Mary Tyler Moore Show 43 42 The Monkees The Mary Tyler Moore Show 13 24 The Monkees F Troop 7 11 JAG The Muppet Show 45 34 Happy Days Batman 48 32 The Simpsons Batman 22 29 The Simpsons Route 66 9 25 Monk Gilligan's Island 48 31 The Simpsons Gilligan's Island 48 37 The Greatest American Hero Gilligan's Island 36 28 The Greatest American Hero Mad About You 9 10 Baretta Gilligan's Island 32 31 The Simpsons All in the Family 33 10 X-Men: The Animated Series All in the Family 31 28 The Twilight Zone St. Elsewhere 14 46 The Twilight Zone All in the Family 13 27 Doctor Who Game of Thrones 29 39 Doctor Who Game of Thrones 25 30 Doctor Who Parks and Recreation 19 6 Poirot The Muppet Show 49 50 Happy Days Rawhide 37 51 The Pink Panther Show Rawhide 37 52 The Pink Panther Show Power Rangers 20 6 Orange Is the New Black Rawhide 27 52 The Pink Panther Show Diff'rent -

Antland Credits.Pdf

Roy B. Yokelson TOUCHSTONE Get Under", "High and Dizzy" Voice-Over Coach, "Billy Bathgate" (1991) Communicator Awards, Sound Designer, COLUMBIA Telly Awards Recording Engineer, "Biloxi Blues" (1988) A & E - BIOGRAPHY Producer, Director "Kramer vs. Kramer" (1979) Jackie Robinson Jackie Onassis (917) 642-9999 TELEVISION/DOCUMENTARY HBO (973) 338-7338 "An Old Fashioned Story HGTV / CITY LIGHTS TELEVISION (Ask Me Again)" "Don't Sweat It" Men And Women II– "Return [email protected] PBS / ROBERT MacNEIL to Kansas City" Skype: antland_productions “Do You Speak American?” ABC CBS SPORTS "The Marie Balter Story" AFFILIATIONS Emmy Award winner–Sound Design, starring Marlo Thomas SAG, AFTRA, 1992 Winter Olympics TITUS/BULLS BLOOD NARAS, IBEW The Sports Illustrated For Kids Show "Johnny Bull" starring Jason CBS / NBC / ABC Robards and Colleen Dewhurst The Daytime Emmy Awards Show Live and prerecorded Music ANIMATION FEATURE FILMS and PARAMOUNT SOUNDTRACK ALBUMS The Jon Stewart Show PBS KIDS JEAN BACH “Piggley Winks” MR. MUDD "The Spitball Story" Videographer CARTOON NETWORK "Ghost World" (2001) Award, Telly Award "Classic Cartoon" WOODY ALLEN "A Great Day In Harlem" - HANNA BARBERA / RALPH BAKSHI "Whatever Works" (2009) Academy Award Nominee, WHAT A CARTOON!– “Melinda and Melinda” (2005) Chicago Award, "Malcolm and Melvin" "Sweet and Lowdown" (1998) Communicator Award, Telly Award HANNA-BARBERA "Celebrity" (1997) PBS / AMERICAN MASTERS Pebbles Cereal/Jetsons–RadioShack/ "Everyone Says I Love You" (1996) Bluesland Cartoon Network "Mighty Aphrodite" -

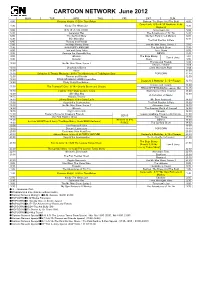

CARTOON NETWORK June 2012

CARTOON NETWORK June 2012 MON. TUE. WED. THU. FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 Princess Knight 6/26~Time Bokan Batman: The Brave And The Bold 4:00 Camp Lazlo 6/9~4:30 Backkom 4:45 Kimba The White Lion 4:30 Raymond 4:30 5:00 BEN 10: ALIEN FORCE Tomorrow's Joe 5:00 5:30 Generator Rex The Adventures of Tin Tin 5:30 6:00 The Garfield Show My Gym Partner's A Monkey 6:00 Mini Moo Moo 6:30 The Pink Panther & Pals 6:30 6:45 Thomas and Friends 7:00 The Bugs Bunny Show The Mr. Men Show, Series 1 7:00 7:30 Hi Hi PUFFY AMIYUMI The Garfield Show 7:30 8:00 Tom and Jerry Tales Teen Titans 8:00 8:30 Courage the Cowardly Dog BEN10 8:30 Moomin The Bugs Bunny 9:00 9:00 Tom & Jerry 9:30 Chowder Show 9:30 Thomas and Friends 10:00 10:00 The Mr. Men Show, Series 1 Aesop's Theater 10:15 10:30 Untalkative Bunny Little Moonlight Rider 10:30 11:00 Babar 11:00 11:30 Sylvester & Tweety Mysteries 6/6~The Adventures of Paddington Bear POPCORN 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends 12:00 12:20 PINGU,MIO&MAO SERIES,Symfollies Dastardly & Muttuley 6/10~Popeye 12:30 12:40 Pinky Dinky Doo,Gazoon Thomas and Friends 13:00 13:00 The Powerpuff Girls 6/14~Charlie Brown and Snoopy PINGU,KIPPER,MuMuHug season 3&4 13:15 13:30 Triplets 6/4~Baby Looney Tunes Snailympics,Hilltop Hospital 13:40 Mini Moo Moo 14:00 A Collection of Fables 14:00 14:15 Aesop's Theater 14:30 Johnny Bravo 6/6~Camp Lazlo Mr. -

Animation 60 Bidder Number:______Please Print All Information Business Phone:______Mr./Mrs./Ms.______Fax: ______

Animation Auction 60 December 20, 2013 Animation Auction 60 AUCTION FRIDAY DECEMBER 20, 2013 11:00 AM PST LIVE • MAIL • PHONE • FAX • INTERNET PLACE YOUR BID OVER THE INTERNET! PROFILES IN HISTORY WILL BE PROVIDING INTERNET-BASED BIDDING TO QUALIFIED BIDDERS IN REAL-TIME ON THE DAY OF THE AUCTION. FOR MORE INFORMATION, PLEASE VISIT US @ WWW.PROFILESINHISTORY.COM CATALOG PRICE PRESIDENT/CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER $35.00 Joseph M. Maddalena AUCTION LOCATION ACQUISITIONS/CONSIGNMENT RELATIONS PROFILES IN HISTORY Brian R. Chanes 26901 AGOURA ROAD, SUITE 150 CALABASAS, CA 91301 CREATIVE DIRECTOR Lou Bustamante AUCTION PREVIEW AT VAN EATON GALLERIES OFFICE MANagER AppOINTMENT ONLY Suzanne Sues VAN EATON GALLERIES 13613 VENTURA BOULEVARD EDITOR SHERMAN OAKS, CA 91423 Joe Moe TELEphONE AUCTION ASSOCIATE 1-310-859-7701 Rick Grande FAX ARCHIVE SPECIALIST 1-310-859-3842 Raymond Janis E-MAIL ADDRESS AUCTION ASSOCIATE [email protected] Kayla Sues WEBSITE PHOTOGRAPHY ASSOCIATE WWW.PROFILESINHISTORY.COM Charlie Nunn SOCIAL MEDIA SPECIALIST Julie Gauvin LAYOUT EDITOR Edward Urrutia Find us on @ www.facebook.com/ProfilesInHistory Find us on @ twitter.com/pihauctions Dear Collector: Welcome to our Winter 2013 Animation Auction! We are pleased to present this offering of over 500 unique lots of amazing art. Working in partnership with Van Eaton Galleries, we have assembled some of the most impor- tant animation artwork ever created by Walt Disney, Walter Lantz, Hanna-Barbera, Warner Bros., Charles Schulz, and many others. You will undoubtedly find your favorite characters among this collection. Here are a few of the highlights: • Original production cels and matching background from Famous Studios’ Boo Moon. -

CARTOON NETWORK April 2015

CARTOON NETWORK April 2015 MON. TUE. WED. THU. FRI. SAT. SUN. 4:00 My Gym Partner's A Monkey 4/17~The Powerpuff Girls Courage the Cowardly Dog 4:00 5:00 Adventure Time Tomorrow's Joe(J) The Bugs Bunny Show 5:00 Peter Rabbit 6:00 6:00 Chowder Thomas and Friends 6:30 7:00 The Amazing World of Gumball HCA The Fairytaler 7:00 8:00 The Mr. Men Show, Series 2 4/16~Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 4) The Amazing World of Gumball 8:00 9:00 The Garfield Show season 2 4/8~The Garfield Show season 3 4/27~The Garfield Show The Tom and Jerry Show 9:00 4/5~Mr. Bean Animated: series 10:00 The Pink Panther & Pals 2 POPCORN Clarence 10:00 The Looney Tunes Show2 11:00 The Adventures of Peter Pan Regular Show MGM Cartoons BEN 10: OMNIVERSE 11:30 12:00 Thomas and Friends Charlie Brown and Snoopy 12:00 12:30 Picture Book Animation Collection Thomas and Friends 12:30 13:00 Aesop's Theater 4/16~PINGU Peter Rabbit 13:00 13:15 Clifford the Big Red Dog 4/2~HANAKAPPA(J) THE SANDPIXIES 、Cheburashka Arere?(J)、MIO&MAO 13:30 The New Adventures of Madeline 4/30~Madeline 13:30 SERIES、The Adventures of Pim & Pom HANAKAPPA(J) 14:00 14:00 Tom and Jerry Tales The Powerpuff Girls Aesop's Theater 14:15 14:30 The Tom and Jerry Show The Adventures of Peter Pan 14:30 15:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Oggy & the Cockroaches (season 4) 15:00 Tom & Jerry 16:00 16:00 The Garfield Show 4/17~The Garfield Show season 2 Keshikasu kun(J) 16:30 Regular Show 16:45 17:00 Adventure Time The Amazing World of Gumball 17:00 18:00 The Looney Tunes Show The Bugs Bunny Show Adventure Time 18:00 4/9~ TEEN TiTANS GO! 19:00 19:00 The Amazing World of Gumball Mr.