You Must Unlearn What You Have Learned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

星球大战论坛star Wars China 编者说明目录星球大战常见问题解答

星球大战论坛 STAR WARS CHINA 编者说明 本手册最初由星球大战论坛版主雏龙先生、绿熊等人编写,凝结了诸多同好的心血,其内容原载于百度星球大战贴吧 后因变故撤除,现经重新整合、润色、校对和排版在星球大战论坛发布。为便于解答星战迷普遍困惑的问题,普及星战 文化,现特将该系列文章整理成册,并增加了截至 2013 年的最新资料,编为三篇:星球大战常见问题解答、星战历 史常见问题解答、星战电影误译汇总。这些只是星战迷常见问题的冰山一角,还需不断更新、完善。 因编者水平有限,错漏之处在所难免,欢迎指正、探讨。 星球大战论坛,2013 年 10 月 目 录 星球大战常见问题解答.........................................................................................1 星球大战共有几部?应该按照什么样的顺序观看?...................................................................................1 克隆人战争动画有几部,分别发生在什么时间?......................................................................................1 星球大战是先有电影,还是先有小说?...................................................................................................2 什么是 EU?.............................................................................................................................................. 2 星球大战的历史是如何纪年的?.............................................................................................................2 星球大战的有关资料,如何识别是正确的还是错误的?.............................................................................4 太空中为什么会有声音?......................................................................................................................5 为什么《绝地归来》末尾出现的阿纳金灵魂,是年轻时的形象?................................................................5 星球大战电影的重制版与原版都有哪些不同?..........................................................................................5 星战历史常见问题解答.......................................................................................12 “原力的平衡” 是什么意思?.................................................................................................................12 -

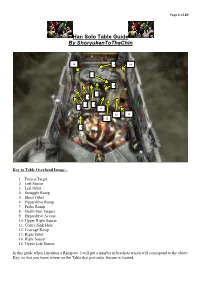

Han Solo Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 29 Han Solo Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 15 9 10 7 8 6 4 3 5 2 11 13 14 12 1 Key to Table Overhead Image – 1. Frozen Target 2. Left Saucer 3. Left Orbit 4. Smuggle Ramp 5. Shoot Orbit 6. Hyperdrive Ramp 7. Probe Ramp 8. Death Star Targets 9. Hyperdrive Access 10. Upper Right Saucer 11. Centre Sink Hole 12. Courage Ramp 13. Right Orbit 14. Right Saucer 15. Upper Left Saucer In this guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the above Key, so that you know where on the Table that particular feature is located. Page 2 of 29 TABLE SPECIFICS Notice: This Guide is based on the gameplay of the Zen Pinball 2 (PS4/PS3/Vita) version of the Table on default controls. Some of the controls will be different on the other versions (Pinball FX 2, Star Wars Pinball, etc...), but everything else in the Guide remains the same. INTRODUCTION This Table came about as a result of the partnership between Zen Studios and LucasArts; this license allowed Zen to produce Tables based on the Star Wars License. As of now Zen has been licensed to release 10 Star Wars Themed Tables but with more Tables possible in the future. The third batch of Tables was released in a 4 Pack which include the Tables; Han Solo, Droids, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope & Masters of The Force. This Table is of course Han Solo; it pays homage to one of the most iconic Movie characters of all time. -

Do's and Don'ts of AAC - Wait Time Providing Enough Time to People Who Use AAC Is Very Important, As Using AAC to Communicate Takes Time

Do's and Don'ts of AAC - Wait time Providing enough time to people who use AAC is very important, as using AAC to communicate takes time. We as communication partners need to provide enough of it for the person using AAC to claim their turn in the conversation, to process what was said and what they want to say and then compose their message. There is a reason why providing wait time appears on so many lists of supports and interventions for AAC users. All people who use AAC, whether young and just learning or accomplished adult, need enough time. Using AAC to communicate takes time and we as communication partners need to provide enough of it for the person using AAC to claim their turn in the conversation, to process what was said and what they want to say and then compose their message. This one should be easy but for so many of us, it’s hard and takes practice. Regardless of whether the AAC is an app on an iPad, a dedicated device or a sheet of paper, it takes time and it’s up to us to make sure that it is provided. The perfect pause In her PrAACtical AAC article, On Not Talking, Carole Zangari describes it as the “perfect pause”. She reminds us, “There is power in the perfect pause.” Why provide enough wait time? To let the user know it’s their turn To provide time for the user to process what you said To give the user time to take their turn And it works! A study by Hilary Johanna Mathis entitled “The effect of pause time upon the communicative interactions of young people who use augmentative and alternative communication”, demonstrated that when a communication partner provides pause time, the AAC user is more likely to claim their turn and respond with more words. -

Darth Vader Vol. 2: Shadows and Secrets Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STAR WARS: DARTH VADER VOL. 2: SHADOWS AND SECRETS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Kieron Gillen | 136 pages | 05 Jan 2016 | Marvel Comics | 9780785192565 | English | New York, United States Star Wars: Darth Vader Vol. 2: Shadows And Secrets PDF Book When Yoda tells Obi-Wan's ghost that "there is another" in Episode V , many speculated about what in the world this was referencing. For additional information, see the Global Shipping Program terms and conditions - opens in a new window or tab This amount includes applicable customs duties, taxes, brokerage and other fees. Check out all my cool collectibles I have for auction! In fact, they even make changes after the movie wraps in post-production using computers and voiceover dialogue. Report item - opens in a new window or tab. While Kevin is a huge Marvel fan, he also loves Batman because he's Batman and is a firm believer that Han shot first. Darth Vader 21 NM- 9. Darth Maul's appearance and actions, however, are a remarkable piece of misdirection engineered by Darth Sidious a. Shipping and handling. Fill in your details below or click an icon to log in:. Save huge on combined shipping!!! Right now I guess it depends on who you believe, but it seems like a rather odd rumor for Pegg to start. There's the theory floating around that the most-loathed character in the galaxy is actually a Sith lord behind all of the destruction that's been wrought, so does that mean all will be revealed in The Force Awakens? In the end, it was the deepest the animated series has ever ventured into the main trilogy, and it worked to perfection on a fundamental level. -

Digital Writing Anthology July 2016

“A writer is someone who has taught his mind to misbehave.” Oscar Wilde Digital Writing Anthology July 2016 Teachers Daryl Myers Zoe Breen Campers Daryl Myers If I Were in Charge of the World If I were in charge of the world, (and what a wonderful world that would be) I would cancel Cruelty, Loneliness, Sorrow, And just about everything else that causes us to suffer... ...unless without them we would know no joy. If I were in charge of the world, People would smile more, even if it was fleeting And take time to notice if you were feeling down. They would do their best to cheer you up, But if you just wanted to be left (alone) They would still understand. If I were in charge of the world would replace technology. Imagination We could ride a cloud thr ough the stars I could visit Hogwarts or Camelot ...or just go sightseeing through time. If I were in charge of the world, There wouldn’t be WRITER’S BLOCK Or traffic jams Or alarm clocks And someone who enjoys taking long naps on lazy Sunday afternoons Would still be allowed to be in charge of the world. Andrew Choi ABCS of What to do when Encountering Brothers Always be on his good side or he will beat you up Be brave in front of him or you will always fear him and that’s not good Caring for him even though he might be mean because he’s still part of your family Do whatever he says for you to do unless it’s something really bad like giving up your prized rock collection or Pokemon cards E-be EXTRA nice to him or face the wrath of his fist or foot Facial expressions are a big no no, especially if they are mean expressions G-don’t grab anything from him because he can get irritated Hunger is what he is, so always, always, always, give him food that he likes and he will be in a good mood. -

|||GET||| the Dharma of Star Wars 2Nd Edition

THE DHARMA OF STAR WARS 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Matthew Bortolin | 9781614292869 | | | | | X-Wing Second Edition is the best version of the classic miniatures game ever made Retrieved April 25, Retrieved March 21, Retrieved May 19, As a matter of fact, the trilogy I mentioned above which I'll pitch if I'm invited to do another book would have one book heavily involving Thrawn and the Chiss. I was missing more context and references on the "Buddhist" side. Retrieved December 25, Star Wars: The Annotated Screenplays. The Special Edition changed the performance to "Jedi Rocks". President The Dharma of Star Wars 2nd edition Reagan in said "the Force is with us", referring to the United Statesto create the Strategic Defense Initiative to protect against Soviet ballistic missiles. Retrieved September 7, Archived from the original on October 12, Enlarge cover. Combat plays out with the help of a few custom-made dice. He most famous lines reflect ancient wise words from the Buddha Many of the other "good" characters had their moments as well, it wasn't all Yoda. June 2, Star Wars. Fans have coined the phrase " Han shot first " to protest The Dharma of Star Wars 2nd edition change, [39] which according to Polygon alters Han's moral ambiguity and his fundamental character. Escape the Present with These 24 Historical Romances. It doesn't seem to be connected with ethics or a code of decent behavior, either. May 25, Matt Kelland rated it liked it. Springer International Publishing. I think either of those beliefs lead to more suffering than actually confronting evil or trying to better oneself. -

Star Wars, Épisode IV : Un Nouvel Espoir

Star Wars, épisode IV : Un nouvel espoir La Guerre des étoiles (Star Wars) est un film américain de science-fiction de type space opera sorti en 1977 écrit et réalisé par George Lucas. À partir de l'an 2000, il est exploité sous le nom Star Wars, épisode IV : Un nouvel espoir Star Wars, épisode IV : (Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope). Un nouvel espoir C'est le premier opus de la saga Star Wars par sa date de sortie, mais le quatrième selon l'ordre chronologique de l'histoire. Il est le premier volet de la trilogie originale qui est constituée également des films L'Empire contre-attaque et Le Retour du Jedi. Ce film est aussi le troisième long métrage réalisé par Lucas. Note 1 L'histoire de cet épisode se déroule presque dix-neuf ans après les événements de La Revanche des Sith (sorti en 2005). L'intrigue se concentre sur l'Alliance rebelle, une organisation qui tente de détruire la station spatiale Étoile Logo du film Un nouvel espoir. noire, l'arme absolue du très autoritaire Empire galactique. Mêlé malgré lui à ce conflit galactique, le jeune ouvrier agricole Luke Skywalker s'engage au sein des forces rebelles après le massacre de sa famille par des soldats Titre original Star Wars Episode IV: A impériaux. New Hope George Lucas commence l’écriture du scénario en 1973. La préproduction du film dure deux ans. Le tournage en lui- Réalisation George Lucas même se déroule de mars à juillet 1976, principalement aux studios d'Elstree, en Angleterre mais aussi en extérieur en Scénario George Lucas Tunisie. -

Transcript of Han Shot Solo

1 This is Studio 360, I’m Eric Molinsky It was an era much like our own but with clunky cell phones, and sluggish Internet connection. And like today, there was a national fervor because Star Wars was coming back to the theaters – digitally restored, with new special effects, new scenes even! Josh Gilliland was in college. He was of that generation that had only seen Star Wars on VHS. This was going to be his chance to experience what we all experienced in ‘77 – and then some. But something happened that changed the course of movie fandom forever. JG: So let’s set the scene, we’re in the bar, cantina, Of course, when we first meet Han Solo, he’s in a seedy bar on Tatooine. As he’s about to accept a job flying Ben and Luke to Aldaran – with no questions asked. Han is psyched, it’s a lot money, but suddenly, he’s stopped by a green, bug-eyed creature called Greedo. Of course, Josh knew this scene very well. We all did. JG: And this exchange takes place at gun point.Words are said and we get threats and Han says over my dead body, that’s the idea, I’ve been looking forward to this a long time. In case you can’t tell, Josh is a lawyer. JG: Han replies yeah, I bet you have. Blaster shot and the rest is movie history. But not anymore. George Lucas had re-edited the scene so that Greedo fires first – and hits the wall next to Han. -

No Wrong Way to Pay with Secure Cards

Not all merchants, however, are prepared for the new technology (pay-at-the-pump gas stations are one example). So, for a few years, you'll be seeing cards with chips as well as stripes. You'll need personal identification numbers (PINs) with some cards, but not others. That's why you'll be asked to use your card differently at different stores. • Some merchants will ask you to insert your card into a reader that scans the chip. • Some merchants will ask you to swipe the stripe. • Some merchants will ask for your PIN, while others will ask you to sign your name. • Some won't ask for a signature or a PIN. • Some will ask you to choose debit or credit when you're paying with a debit card. (Either way, the money will still come out of the No wrong way to pay account assigned to the card.) • Some will automatically run debit purchases as debit or automatically as a credit. with secure cards. • And some merchants won't know what to do, as the technology is just starting to reach some stores and communities. Chip, PIN, sign, or swipe: It all works. “When it comes to spending money, use Remember when DVDs came out, threatening to replace VHS tape? Images were sharper, storage was easier, and you didn't need to rewind the chip whenever you can.” the tape after every use. Your experience will become more predictable as chips become the Despite the benefits of DVDs, there was a transition period when new standard. But there will always be some variation at the register. -

Reinventing the Media Franchise

REINVENTING THE MEDIA FRANCHISE: CONTEXT, MEANING AND DISCOURSE by Felan Parker, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario April 2009 © 2009, Felan Parker Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51968-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-51968-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nntemet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Transcript of Workin' on the Death Star

1 You’re listening to Imaginary Worlds, a show about how we create them and why we suspend our disbelief. I’m Eric Molinsky. I was at WinterCon recently, which is like a miniature ComicCon held at a Casino in Queens. I like going to these mini-ComicCons because they’re more casual than the big ones, and you can get to know people. I was talking to this guy named John. He’s a member of the 501st Legion. It’s a charity organization of people who dress up as Stormtroopers. And their costumes are dead-on perfect. He does it because he loves seeing the faces of kids when he marches into a room. JOHN: I think if a Stormtrooper walked into your classroom, you’re lose your mind before Han Solo. EM: And with costume you can be Stormtrooper, You can’t be Harrison Ford of 1983 all the sudden. JOHN: And who would want to be? But yes, there’s a certain level of autonomy, nobody knows what you look lie you get a lot more attention wearing helmet but all for good cause, raise money for charity our love of SW made that possible. Being inside the Stormtrooper uniform, do you sympathize for them? JOHN: Also ways Wilhelm scream, guy who bumped head on DS, look Luke and Han, look Rebel Legion, they have good Han’s and Luke’s but I don’t know maybe the Dark Side appeals to me than the light side. It’s a lot more fun. I’ve been thinking about Stormtroopers lately for two reasons. -

Book Review Ken Derry / John C. Lyden (Eds.), the Myth Awakens

Jade Weimer Book Review Ken Derry / John C. Lyden (eds.), The Myth Awakens Canon, Conservatism, and Fan Reception of STAR WARS Eugene: Cascade Books, 2018, xxi + 173 pages, ISBN: 978-1-5326-1973-1 When asked to review this book, I was a little hesitant to do so, because my familiarity with the Star Wars franchise is limited at best. Yet I would now argue that extensive knowledge of the Star Wars mythology is not a prereq- uisite for engaging with this text in a meaningful way, as issues raised by the contributors provide key insights into the discipline of religious studies as well as the intersection of religion and media which are useful in a broader context, including questions of canonization, collective memory, legitimacy, race, and gender. And perhaps one of the most exciting questions addressed in the book (for me!) is the role of music in myth-making. Ken Derry’s preface offers an introduction to the volume and he empha- sizes the need for fun in scholarship. He contends that we as scholars ought to take ourselves less seriously in certain ways. The “enduring appeal” (11) of Star Wars is linked to the fun one derives from creating meaning through engagement with the films, music, and characters. Derry’s concurrent use of theory and humour in the opening section is both fun to read and theoreti- cally rigorous. The first chapter, by John C. Lyden, argues that both the Original Trilogy and the newer films demonstrate moral and political ambiguity as the lines be- tween villain and hero are blurred.