Ontological Insecurity in "Game of Thrones" and Other Fantastic Transmedial Storyworlds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding

Transmedia Storytelling Hyperdiegesis, Narrative Braiding and Memory in Star Wars Comics William Proctor Since at least the turn of the twentieth century, the comic book medium has grown in dialogue alongside other media forms, both old and new, underscored by what is commonly described as adaptation. In basic terms, adaptation refers to a process whereby stories are lifted from one medium and replanted in another. Of course, the process is more complicated than that as different media each bring different creative requirements and, as a result, adaptation is never simply about reproducing a story in exactly the same way—although it is about reproduction, to some degree. Put simply, adaptation refers to the retelling of a story in a new media location. For example, each installment of Warner Bros.’ Harry Potter film series—from Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows—are adaptations of novels written by J.K Rowling, each ‘retelling’ the same story in the process from book-to-film. The caveat here is that such a retelling also involves revising narrative elements, and even editing or reframing scenes from the ‘source’ text to better-fit the ‘target’ medium. Variations as well as repetition are key factors to consider, as adaptation theorist Linda Hutcheon notes (2006). The contemporary landscape is brimming with adaptations of all sorts, but perhaps the most common example in the twenty-first century are the bevvy of film and TV series based on comic books, many of them produced by the ‘big two’ superhero publishers, Marvel and DC, as film scholar Terence McSweeney argues: “We are living in the age of the superhero and we cannot deny it” (2018, 1). -

Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 1 year for only $29.99* *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. Subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com, or send a check or money order to: Celebrations Press PO BOX 584 Uwchland, PA 19480 Be sure to include your name, mailing address, and email address! If you have any questions about subscribing, you can contact us at [email protected] or visit us online! Cover Photography © Garry Rollins Issue 67 Fall 2019 Welcome to Galaxy’s Edge: 64 A Travellers Guide to Batuu Contents Disney News ............................................................................ 8 Calendar of Events ...........................................................17 The Spooky Side MOUSE VIEWS .........................................................19 74 Guide to the Magic of Walt Disney World by Tim Foster...........................................................................20 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................24 Shutters and Lenses by Mike Billick .........................................................................26 Travel Tips Grrrr! 82 by Michael Renfrow ............................................................36 Hangin’ With the Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................38 Bears of Disney Disney Cuisine by Erik Johnson ....................................................................40 -

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 the Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies That This Is the Approved Version of the Following Dissertation

Copyright by Jason Todd Craft 2004 The Dissertation Committee for Jason Todd Craft Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions Committee: Adam Z. Newton, Co-Supervisor John M. Slatin, Co-Supervisor Brian A. Bremen David J. Phillips Clay Spinuzzi Margaret A. Syverson Fiction Networks: The Emergence of Proprietary, Persistent, Large- Scale Popular Fictions by Jason Todd Craft, B.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December, 2004 Dedication For my family Acknowledgements Many thanks to my dissertation supervisors, Dr. Adam Zachary Newton and Dr. John Slatin; to Dr. Margaret Syverson, who has supported this work from its earliest stages; and, to Dr. Brian Bremen, Dr. David Phillips, and Dr. Clay Spinuzzi, all of whom have actively engaged with this dissertation in progress, and have given me immensely helpful feedback. This dissertation has benefited from the attention and feedback of many generous readers, including David Barndollar, Victoria Davis, Aimee Kendall, Eric Lupfer, and Doug Norman. Thanks also to Ben Armintor, Kari Banta, Sarah Paetsch, Michael Smith, Kevin Thomas, Matthew Tucker and many others for productive conversations about branding and marketing, comics universes, popular entertainment, and persistent world gaming. Some of my most useful, and most entertaining, discussions about the subject matter in this dissertation have been with my brother, Adam Craft. I also want to thank my parents, Donna Cox and John Craft, and my partner, Michael Craigue, for their help and support. -

星球大战论坛star Wars China 编者说明目录星球大战常见问题解答

星球大战论坛 STAR WARS CHINA 编者说明 本手册最初由星球大战论坛版主雏龙先生、绿熊等人编写,凝结了诸多同好的心血,其内容原载于百度星球大战贴吧 后因变故撤除,现经重新整合、润色、校对和排版在星球大战论坛发布。为便于解答星战迷普遍困惑的问题,普及星战 文化,现特将该系列文章整理成册,并增加了截至 2013 年的最新资料,编为三篇:星球大战常见问题解答、星战历 史常见问题解答、星战电影误译汇总。这些只是星战迷常见问题的冰山一角,还需不断更新、完善。 因编者水平有限,错漏之处在所难免,欢迎指正、探讨。 星球大战论坛,2013 年 10 月 目 录 星球大战常见问题解答.........................................................................................1 星球大战共有几部?应该按照什么样的顺序观看?...................................................................................1 克隆人战争动画有几部,分别发生在什么时间?......................................................................................1 星球大战是先有电影,还是先有小说?...................................................................................................2 什么是 EU?.............................................................................................................................................. 2 星球大战的历史是如何纪年的?.............................................................................................................2 星球大战的有关资料,如何识别是正确的还是错误的?.............................................................................4 太空中为什么会有声音?......................................................................................................................5 为什么《绝地归来》末尾出现的阿纳金灵魂,是年轻时的形象?................................................................5 星球大战电影的重制版与原版都有哪些不同?..........................................................................................5 星战历史常见问题解答.......................................................................................12 “原力的平衡” 是什么意思?.................................................................................................................12 -

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media

Alternate Universe Fan Videos and the Reinterpretation of the Media Source Introduction According to the Francesca Coppa, American scholar and co-founder of the Organization for Transformative Works1, fan videos are “a form of grassroots filmmaking in which clips from television shows and movies are set to music.”2 Fan videos are commonly referred to as: fanvid, songvid, vid, AMV (for Anime Music Video); their process of creation is called vidding and their editors (fan)vidders. While the “media tradition” described above in Francesca Coppa‟s definition is a crucial part of the fan video production, many other fan videos are created for anime, especially Asian ones (AMV), for video games (some of them called Machinima), or even for other subjects, from band tributes to other types of remix. The vidding tradition – in its current “shape” – goes back to the era of the first VCR; but the very first fan videos may be traced back to the seventies in a slideshow format. When channel mixers and numerous machines available to a large group of consumers emerged, this fan activity easily became an expanding one amongst the fan communities, who were often interested in new technology, whatever era it is. Vidding has now become a digital process, thanks to the expansion of computer and related technical means, including at least semiprofessional editing software. It seems relevant to point out how rare it is that a vidder goes through editing training when they begin to create fan videos, or even become a professional editor later on. Of course, exceptions exist, but vidding generally remains a hobby. -

Be Mindful of the Future: Information and Knowledge Management in Star Wars Tie-In Fiction

Volume 13 Spring 2017 djim.management.dal.ca | Be mindful of the future: information and knowledge management in Star Wars tie-in fiction Diana Castillo School of Information Management, Dalhousie University Abstract In the last fifty years, media franchises have been using tie-in fiction to expand their universes and tell stories outside the main source material. This paper examines how information management is used specifically in Star Wars tie-in fiction and its recent transition to using knowledge management. To start, this paper looks at the history of tie-in fiction from its roots in the 1960s to the modern day, before transitioning to the role of brand managers and editors as information managers. Then, this paper documents the history of Star Wars tie-in fiction and how information management strategies were implemented through 2014 and how it impacted the franchise’s internal continuity. Finally, this paper examines the recent move towards a unified canon and how this shift towards knowledge management has impacted storytelling. This paper concludes that while it is too early to evaluate its results, Star Wars was uniquely situated among franchises to move towards knowledge management through its prior information management efforts. Introduction universes and tell stories they may not be able to tell otherwise. Creating a well-run line In today’s entertainment environment, of tie-in fiction requires coordination between popular franchises are rarely limited to one authors, publishing houses, and the licensing type of media. They license their products company through information management. across various different formats to engage In the context of this paper, information fans and expand their footprint in popular management is defined as working with culture as much as possible. -

Bollywood Produces More Movies in a Year Than Hollywood

a-z CONTENTS a ANALYZE, ANALYZE, ANALYZE by Klara Gavran P6 b BLOCKBUSTER PHENOMENON by Klara Malnar P12 c CINEMAS, ARE THEY DYING? by Klara Malnar P17 d DID YOU KNOW? by Irma Jakić P22 e ENTERTAINMENT MARKETING IN 2019 by Klara Malnar P27 f FAMOUS CELEBRITY ENDORSEMENTS by Irma Jakić P30 g GO BIG OR GO HOME by Irma Jakić P31 h HOLLYWOOD VS BOLLYWOOD by Klara Malnar P35 i I WANT TO THANK THE ACADEMY…AND MY CAMPAIGN STRATEGIST by Klara Malnar P38 j JOYS OF DIGITALIZATION by Klara Gavran P43 k KEEPING UP WITH THE STREAMING SERVICES by Klara Gavran P47 l LEANING INTO SOCIAL LISTENING by Klara Gavran P51 m MUSICIANS TO ACTORS AND VICE VERSA by Irma Jakić P60 n NOT YOUR AVERAGE MARKETING CAMPAIGN by Klara Gavran P62 o OFF-CAMERA: ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY BY THE DOLLAR by Irma Jakić P71 p PR NIGHTMARE, BUT LONG OVERDUE by Iva Anušić P75 q QUICK FIX by Iva Anušić P79 r RAZZIES by Irma Jakić P88 s SOCIAL MEDIA’S IMPACT ON THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY by Klara Malnar P90 t THE COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS: HOW CAN STREAMING SERVICES BENEFIT by Klara Gavran P96 u USER-GENERATED CONTENT by Klara Malnar P99 v VIEWER’S CHOICE by Klara Gavran P103 w WHAT ABOUT FILM FESTIVALS? by Klara Malnar P105 x X FACTOR by Irma Jakić P111 y YHBT (YOU HAVE BEEN TROLLED) CULTURE by Iva Anušić P113 z ZOMBIES by Irma Jakić P116 a ANALYZE, ANALYZE, ANALYZE “Pay attention to what the people and the start a few months, half a year, or even a whole press are talking about. -

Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World Across Distinct Media and Environments

Transmedia Practice: Theorising the Practice of Expressing a Fictional World across Distinct Media and Environments by Christy Dena A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) School of Letters, Art and Media Department of Media and Communications Digital Cultures Program University of Sydney Australia Supervisor: Professor Gerard Goggin Associate Supervisor: Dr. Chris Chesher Associate Supervisor: Dr. Anne Dunn 2009 Let’s study, with objectivity and curiosity, the mutation phenomenon of forms and values in the current world. Let’s be conscious of the fact that although tomorrow’s world does not have any chance to become more fair than any other, it owns a chance that is linked to the destiny of the current art [...] that of embodying, in their works some forms of new beauty, which will be able to arise only from the meet of all the techniques. (Francastel 1956, 274) Translation by Regina Célia Pinto, emailed to the empyre mailing list, Jan 2, 2004. Reprinted with permission. To the memory of my dear, dear, mum, Hilary. Thank you, for never denying yourself the right to Be. ~ Transmedia Practice ~ Abstract In the past few years there have been a number of theories emerge in media, film, television, narrative and game studies that detail the rise of what has been variously described as transmedia, cross-media and distributed phenomena. Fundamentally, the phenomenon involves the employment of multiple media platforms for expressing a fictional world. To date, theorists have focused on this phenomenon in mass entertainment, independent arts or gaming; and so, consequently the global, transartistic and transhistorical nature of the phenomenon has remained somewhat unrecognised. -

Entertainment Architecture

Entertainment Architecture Constructing a Framework for the Creation of an Emerging Transmedia Form by Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Dipl.-Kfm. European Business School, Oestrich-Winkel, Germany A dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ARC Centre of Excellence for Creative Industries and Innovation Creative Industries Faculty Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Entertainment Architecture Keywords film movie transmedia entertainment transmedia storytelling pervasive games ubiquitous games agency form evolution entrepreneurship business industry creative destruction marketing promotion — II — Adalbert (Woitek) Konzal Entertainment Architecture Abstract This thesis investigates the radically uncertain formal, business, and industrial environment of current entertainment creators. It researches how a novel communication technology, the Internet, leads to novel entertainment forms, how these lead to novel kinds of businesses that lead to novel industries; and in what way established entertainment forms, businesses, and industries are part of that process. This last aspect is addressed by focusing on one exemplary es- tablished form: movies. Using a transdisciplinary approach and a combination of historical analysis, industry interviews, and an innovative mode of ‘immersive’ textual analysis, a coherent and comprehensive conceptual framework for the creation of and re- search into a specific emerging entertainment form is proposed. That form, -

Nov 2019-Jan 2020 Grand

THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF GRAND CINEMAS GRANDFREE NOV 2019-JAN 2020 20202020 MUSTMUST LISTLIST ONE ON ONEi with thei massivei A-list castiMIDWAY THETHE BATTLEBATTLE THATTHAT TURNEDTURNED THETHE TIDESTIDES OFOF WARWAR Movie_Guide_16.5x23.5.pdf 1 10/11/19 10:54 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K GOGRAND #alwaysentertaining SOCIALISE TALK MOVIES, WIN PRIZES @GCLEBANON CL BOOK NEVER MISS A MOVIE WITH E/TICKET, E/KIOSK AND THE GC MOBILE APP. EXPERIENCE FIRSTWORD ISSUE 126 FEAT. DOLBY ATMOS A nation makes a stand As we approach the end of an eventful 2019, we are once again LOCATIONS reminded of the power of film to inspire and move us, and to commemorate those pivotal moments in history that define nations. LEBANON KUWAIT We salute the Lebanese people, and wish one and all a prosperous GRAND CINEMAS GRAND AL HAMRA ABC VERDUN LUXURY CENTER new year that lives up to our promise and expectations for a brighter 01 795 697 +965 222 70 334 future. Here’s to the beginning of a new era in 2020. MX4D featuring MX4D ATMOS DOLBY ATMOS Our SPOTLIGHT feature is a fitting tribute to historical moments. GRAND CLASS GRAND GATE MALL Acclaimed director Roland Emmerich gathers an army of stars — +965 220 56 464 GRAND CINEMAS among them Ed Skrein, Patrick Wilson, Mandy Moore and Nick Jonas ABC ACHRAFIEH 01 209 109 — to tell the epic true story of Midway, the battle that turned the tides 70 415 200 NEW of war. FAMILY FIESTA rounds up the kids’ favourites, including Frozen GRAND GRAND CINEMAS CINEMAS II and Norm of the North 3. -

A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse

religions Article A Sense of Presence: Mediating an American Apocalypse Rachel Wagner Department of Philosophy and Religion, Ithaca College, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA; [email protected] Abstract: Here I build upon Robert Orsi’s work by arguing that we can see presence—and the longing for it—at work beyond the obvious spaces of religious practice. Presence, I propose, is alive and well in mediated apocalypticism, in the intense imagination of the future that preoccupies those who consume its narratives in film, games, and role plays. Presence is a way of bringing worlds beyond into tangible form, of touching them and letting them touch you. It is, in this sense, that Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion with a “new visibility” that is much more than “simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more.” I propose that the “new awareness of religion” they posit includes the mediated worlds that enchant and empower us via deeply immersive fandoms. Whereas religious institutions today may be suspicious of presence, it lives on in the thick of media fandoms and their material manifestations, especially those forms that make ultimate promises about the world to come. Keywords: apocalypticism; Orsi; enchantment; fandom; video games; pervasive games; cowboy; larp; West 1. Introduction Michael Hoelzl and Graham Ward observe the “re-emergence” of religion today with a “new visibility” that is “far more complex and nuanced than simple re-emergence of something that has been in decline in the past but is now manifesting itself once more” (Hoelzl and Ward 2008, p. -

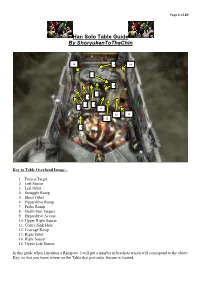

Han Solo Guide by Shoryukentothechin

Page 1 of 29 Han Solo Table Guide By ShoryukenToTheChin 15 9 10 7 8 6 4 3 5 2 11 13 14 12 1 Key to Table Overhead Image – 1. Frozen Target 2. Left Saucer 3. Left Orbit 4. Smuggle Ramp 5. Shoot Orbit 6. Hyperdrive Ramp 7. Probe Ramp 8. Death Star Targets 9. Hyperdrive Access 10. Upper Right Saucer 11. Centre Sink Hole 12. Courage Ramp 13. Right Orbit 14. Right Saucer 15. Upper Left Saucer In this guide when I mention a Ramp etc. I will put a number in brackets which will correspond to the above Key, so that you know where on the Table that particular feature is located. Page 2 of 29 TABLE SPECIFICS Notice: This Guide is based on the gameplay of the Zen Pinball 2 (PS4/PS3/Vita) version of the Table on default controls. Some of the controls will be different on the other versions (Pinball FX 2, Star Wars Pinball, etc...), but everything else in the Guide remains the same. INTRODUCTION This Table came about as a result of the partnership between Zen Studios and LucasArts; this license allowed Zen to produce Tables based on the Star Wars License. As of now Zen has been licensed to release 10 Star Wars Themed Tables but with more Tables possible in the future. The third batch of Tables was released in a 4 Pack which include the Tables; Han Solo, Droids, Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope & Masters of The Force. This Table is of course Han Solo; it pays homage to one of the most iconic Movie characters of all time.