John Gregory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Stored Program Computers

Stored Program Computers Thomas J. Bergin Computing History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Early Thoughts about Stored Programming • January 1944 Moore School team thinks of better ways to do things; leverages delay line memories from War research • September 1944 John von Neumann visits project – Goldstine’s meeting at Aberdeen Train Station • October 1944 Army extends the ENIAC contract research on EDVAC stored-program concept • Spring 1945 ENIAC working well • June 1945 First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC 7/9/2012 2 First Draft Report (June 1945) • John von Neumann prepares (?) a report on the EDVAC which identifies how the machine could be programmed (unfinished very rough draft) – academic: publish for the good of science – engineers: patents, patents, patents • von Neumann never repudiates the myth that he wrote it; most members of the ENIAC team contribute ideas; Goldstine note about “bashing” summer7/9/2012 letters together 3 • 1.0 Definitions – The considerations which follow deal with the structure of a very high speed automatic digital computing system, and in particular with its logical control…. – The instructions which govern this operation must be given to the device in absolutely exhaustive detail. They include all numerical information which is required to solve the problem…. – Once these instructions are given to the device, it must be be able to carry them out completely and without any need for further intelligent human intervention…. • 2.0 Main Subdivision of the System – First: since the device is a computor, it will have to perform the elementary operations of arithmetics…. – Second: the logical control of the device is the proper sequencing of its operations (by…a control organ. -

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards

Computer Development at the National Bureau of Standards The first fully operational stored-program electronic individual computations could be performed at elec- computer in the United States was built at the National tronic speed, but the instructions (the program) that Bureau of Standards. The Standards Electronic drove these computations could not be modified and Automatic Computer (SEAC) [1] (Fig. 1.) began useful sequenced at the same electronic speed as the computa- computation in May 1950. The stored program was held tions. Other early computers in academia, government, in the machine’s internal memory where the machine and industry, such as Edvac, Ordvac, Illiac I, the Von itself could modify it for successive stages of a compu- Neumann IAS computer, and the IBM 701, would not tation. This made a dramatic increase in the power of begin productive operation until 1952. programming. In 1947, the U.S. Bureau of the Census, in coopera- Although originally intended as an “interim” com- tion with the Departments of the Army and Air Force, puter, SEAC had a productive life of 14 years, with a decided to contract with Eckert and Mauchly, who had profound effect on all U.S. Government computing, the developed the ENIAC, to create a computer that extension of the use of computers into previously would have an internally stored program which unknown applications, and the further development of could be run at electronic speeds. Because of a demon- computing machines in industry and academia. strated competence in designing electronic components, In earlier developments, the possibility of doing the National Bureau of Standards was asked to be electronic computation had been demonstrated by technical monitor of the contract that was issued, Atanasoff at Iowa State University in 1937. -

Simon E. Gluck Collection of Photographs of EDVAC and MSAC Computers 1990.232

Simon E. Gluck collection of photographs of EDVAC and MSAC computers 1990.232 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 19, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Audiovisual Collections PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Simon E. Gluck collection of photographs of EDVAC and MSAC computers 1990.232 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical Note .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Additonal Extent Statement ........................................................................................................................... 5 - Page 2 - Simon E. Gluck collection -

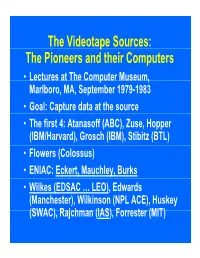

P the Pioneers and Their Computers

The Videotape Sources: The Pioneers and their Computers • Lectures at The Compp,uter Museum, Marlboro, MA, September 1979-1983 • Goal: Capture data at the source • The first 4: Atanasoff (ABC), Zuse, Hopper (IBM/Harvard), Grosch (IBM), Stibitz (BTL) • Flowers (Colossus) • ENIAC: Eckert, Mauchley, Burks • Wilkes (EDSAC … LEO), Edwards (Manchester), Wilkinson (NPL ACE), Huskey (SWAC), Rajchman (IAS), Forrester (MIT) What did it feel like then? • What were th e comput ers? • Why did their inventors build them? • What materials (technology) did they build from? • What were their speed and memory size specs? • How did they work? • How were they used or programmed? • What were they used for? • What did each contribute to future computing? • What were the by-products? and alumni/ae? The “classic” five boxes of a stored ppgrogram dig ital comp uter Memory M Central Input Output Control I O CC Central Arithmetic CA How was programming done before programming languages and O/Ss? • ENIAC was programmed by routing control pulse cables f ormi ng th e “ program count er” • Clippinger and von Neumann made “function codes” for the tables of ENIAC • Kilburn at Manchester ran the first 17 word program • Wilkes, Wheeler, and Gill wrote the first book on programmiidbBbbIiSiing, reprinted by Babbage Institute Series • Parallel versus Serial • Pre-programming languages and operating systems • Big idea: compatibility for program investment – EDSAC was transferred to Leo – The IAS Computers built at Universities Time Line of First Computers Year 1935 1940 1945 1950 1955 ••••• BTL ---------o o o o Zuse ----------------o Atanasoff ------------------o IBM ASCC,SSEC ------------o-----------o >CPC ENIAC ?--------------o EDVAC s------------------o UNIVAC I IAS --?s------------o Colossus -------?---?----o Manchester ?--------o ?>Ferranti EDSAC ?-----------o ?>Leo ACE ?--------------o ?>DEUCE Whirl wi nd SEAC & SWAC ENIAC Project Time Line & Descendants IBM 701, Philco S2000, ERA.. -

John William Mauchly

John William Mauchly Born August 30, 1907, Cincinnati, Ohio; died January 8, 1980, Abington, Pa.; the New York Times obituary (Smolowe 1980) described Mauchly as a “co-inventor of the first electronic computer” but his accomplishments went far beyond that simple description. Education: physics, Johns Hopkins University, 1929; PhD, physics, Johns Hopkins University, 1932. Professional Experience: research assistant, Johns Hopkins University, 1932-1933; professor of physics, Ursinus College, 1933-1941; Moore School of Electrical Engineering, 1941-1946; member, Electronic Control Company, 1946-1948; president, Eckert-Mauchly Computer Company, 1948-1950; Remington-Rand, 1950-1955; director, Univac Applications Research, Sperry-Rand 1955-1959; Mauchly Associates, 1959-1980; Dynatrend Consulting Company, 1967-1980. Honors and Awards: president, ACM, 1948-1949; Howard N. Potts Medal, Franklin Institute, 1949; John Scott Award, 1961; Modern Pioneer Award, NAM, 1965; AMPS Harry Goode Memorial Award for Excellence, 1968; IEEE Emanual R. Piore Award, 1978; IEEE Computer Society Pioneer Award, 1980; member, Information Processing Hall of Fame, Infornart, Dallas, Texas, 1985. Mauchly was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on August 30, 1907. He attended Johns Hopkins University initially as an engineering student but later transferred into physics. He received his PhD degree in physics in 1932 and the following year became a professor of physics at Ursinus College in Collegeville, Pennsylvania. At Ursinus he was well known for his excellent and dynamic teaching, and for his research in meteorology. Because his meteorological work required extensive calculations, he began to experiment with alternatives to mechanical tabulating equipment in an effort to reduce the time required to solve meteorological equations. -

The Manchester University "Baby" Computer and Its Derivatives, 1948 – 1951”

Expert Report on Proposed Milestone “The Manchester University "Baby" Computer and its Derivatives, 1948 – 1951” Thomas Haigh. University of Wisconsin—Milwaukee & Siegen University March 10, 2021 Version of citation being responded to: The Manchester University "Baby" Computer and its Derivatives, 1948 - 1951 At this site on 21 June 1948 the “Baby” became the first computer to execute a program stored in addressable read-write electronic memory. “Baby” validated the widely used Williams- Kilburn Tube random-access memories and led to the 1949 Manchester Mark I which pioneered index registers. In February 1951, Ferranti Ltd's commercial Mark I became the first electronic computer marketed as a standard product ever delivered to a customer. 1: Evaluation of Citation The final wording is the result of several rounds of back and forth exchange of proposed drafts with the proposers, mediated by Brian Berg. During this process the citation text became, from my viewpoint at least, far more precise and historically reliable. The current version identifies several distinct contributions made by three related machines: the 1948 “Baby” (known officially as the Small Scale Experimental Machine or SSEM), a minimal prototype computer which ran test programs to prove the viability of the Manchester Mark 1, a full‐scale computer completed in 1949 that was fully designed and approved only after the success of the “Baby” and in turn served as a prototype of the Ferranti Mark 1, a commercial refinement of the Manchester Mark 1 of which I believe 9 copies were sold. The 1951 date refers to the delivery of the first of these, to Manchester University as a replacement for its home‐built Mark 1. -

John W. Mauchly Papers Ms

John W. Mauchly papers Ms. Coll. 925 Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel. Last updated on April 27, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 2015 September 9 John W. Mauchly papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Series I. Youth, education, and early career......................................................................................... 10 Series II. Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania................................. -

World War II and the Advent of Modern Computing � Based on Slides Originally Published by Thomas J

15-292 History of Computing World War II and the Advent of Modern Computing ! Based on slides originally published by Thomas J. Cortina in 2004 for a course at Stony Brook University. Revised in 2013 by Thomas J. Cortina for a computing history course at Carnegie Mellon University. WW II l At start of WW II (1939) l US Military was much smaller than Axis powers l German military had best technology l particularly by the time US entered war in 1941 l US had the great industrial potential l twice the steel production as any other nation, for example ! l A military and scientific war l Outcome was determined by technological developments l atomic bomb, advances in aircraft, radar, code-breaking computers, and many other technologies Konrad Zuse l German Engineer l Z1 – built prototype 1936-1938 in his parents living room l did binary arithmetic l had 64 word memory l Z2 computer had more advances, called by some first fully functioning electro-mechanical computer l convinced German government to fund Z3 l Z3 funded and used by German’s Aircraft Institute, completed 1941 l Z1 – Z3 were electromechanical computers destroyed in WWII, not rebuilt until years later l Z3 was a stored-program computer (like Von Neumann computer) l never could convince the Nazis to put his computer to good use l Zuse smuggled his Z4 to the safety of Switzerland in a military truck l The accelerated pace of Western technological advances and the destruction of German infrastructure left Zuse behind George Stibitz l Electrical Engineer at Bell Labs l In 1937, constructed -

The Computer As Von Neumann Planned It MD Godfrey* DF Hendry

The Computer as von Neumann Planned It M. D. Godfrey* D. F. Hendry** Address for correspondence: Michael D. Godfrey Durand Bldg. ISL Electrical Engineering Department Stanford University Stanford, CA, 94305 Published in: IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol.14 No.3 * Information Systems Laboratory, Electrical Engineering Department, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. ** T-H Engineering, Inc., Altadena, CA. 1 2 The Computer as von Neumann Planned It M. D. Godfrey D. F. Hendry ABSTRACT We describe the computer which was defined in von Neumann’s unpublished paper First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC, Moore School of Electrical Engineering, University of Pennsylvania, June 30, 1945. Motivation for the architecture and design is discussed, and the machine is contrasted with the EDVAC which was actually constructed. Keywords: architecture, computer, EDVAC, stack, tagged-memory, von Neu- mann architecture. 1. Introduction John von Neumann made a key contribution to the understanding and development of computer architecture and design in his unpublished report titled First Draft Report on the EDVAC [1]. However, in reading work which refers to this report and to the EDVAC (the acronym is defined in [10] to be: Electronic Discrete VAriable Computer) computer which it described some perplexing observations emerge: 1. The constructed EDVAC is usually described as being based on the von Neumann report [1]. 2. The von Neumann report is often described as the collective work of the Moore School group, unfairly given the sole authorship of von Neumann (see, for exam- ple, page xv of [11]). This would suggest that many of the ideas in the report were shared by the Moore School design group and therefore would be expected to appear in the constructed machine. -

Was the Manchester Baby Conceived at Bletchley Park?

Was the Manchester Baby conceived at Bletchley Park? David Anderson1 School of Computing, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, PO1 3HE, UK This paper is based on a talk given at the Turing 2004 conference held at the University of Manchester on the 5th June 2004. It is published by the British Computer Society on http://www.bcs.org/ewics. It was submitted in December 2005; final corrections were made and references added for publication in November 2007. Preamble In what follows, I look, in a very general way, at a particularly interesting half century, in the history of computation. The central purpose will be to throw light on how computing activity at the University of Manchester developed in the immediate post-war years and, in the context of this conference, to situate Alan Turing in the Manchester landscape. One of the main methodological premises on which I will depend is that the history of technology is, at heart, the history of people. No historically-sophisticated understanding of the development of the computer is possible in the absence of an appreciation of the background, motivation and aspirations of the principal actors. The life and work of Alan Turing is the central focus of this conference but, in the Manchester context, it is also important that attention be paid to F.C. Williams, T. Kilburn and M.H.A. Newman. The Origins of Computing in Pre-war Cambridge David Hilbert's talk at the Sorbonne on the morning of the 8th August 1900 in which he proposed twenty-three "future problems", effectively set the agenda for mathematics research in the 20th century. -

Generations of Computers

Chapter- 2 Generations of Computers The rapid development was characterized by the phases of growth, which have come to be called generation of computer. First Generation Basic component – Vacuum Tubes 1940-1956 Vacuum Tube consumed huge amount of electricity. Processing Speed – Slow & Unreliable Machine Heat Generation – Huge amount of Heat generated Size – Bulky & Non – Portable Machine. Lying frequently hardware failure. Instructions – Only Machine Language was used User Friendly – Very Difficult to operate Cost – Production & Maintenance costs was very High Example – ENIAC , UNIVAC , EDVAC, EDSAC, IBM-701 ENIAC - Electronic Numerical Integrator and Calculator UNIVAC - Universal Automatic Computer (First Digital Computer) EDVAC – Electronic discrete variable automatic computer EDSAC – Electronic delay storage automatic calculator IBM – International Business Machine Second Generation Basic component – Transistors & Diodes Processing Speed – More reliable than 1st one Heat Generation – Less amount of Heat generated Size – Reduced size but still Bulky Instructions – High level Language was used ( Like COBOL , ALGOL, SNOBOL) COBOL – Common Business Oriented Language ALGOL – ALGOrithmic Language SNOBOL – StriNg Oriented Symbolic Language User Friendly – Easy to operate from 1st one Cost – Production & Maintenance costs was < 1st Example – IBM 7090, NCR 304 Third Generation Basic component – IC (Integrated Circuits ) 1964-1971 IC is called micro electronics technology integrate a large number of circuit components in to -

967 Computer History and Hardware

967 Computer History and Hardware Prakash C. Rao What is a computer? • Abacus? Slide Rule? • Personal Computer/Macintosh? • iPhone? Blackberry? Palmtop? • iPad? • Server? • Mainframe? Any device capable of computing/processing information Computing = arithmetic/logic/functions Processing = movement/transformation Data = Voice/Image/Video/Text Single Computing Usefulness Technique Grammar Execution Intended Algorithm Programming Run Use Memory Stored Central Program Processing Unit Input & Instructions Data Output More Concepts Computer Computer Computer 1 2 4 Network Network Inter-networking Computer 3 Computer Invoke Distant Tasks Computer 6 Exchange Data 5 Send/Receive Files What drove the evolution? A few examples • Military need for competitive advantage – Code breaking/Ciphers – Ballistic Missile computations – Space launch and Mission Management – Nuclear Weapon Design • Solving large, complex statistical, mathematical scientific and engineering problems – Weather calculations and predictions – Telephone call routing and transmission – Dispatch of truck fleets, trains, airliners – Design of very complex systems – Decennial Census – National Elections – Astrophysics – Quantum Mechanics • Supporting Business Processes – Payroll processing – Taxes and accounting – Human Resource Management Drivers .. • Personal and Corporate Productivity – Spreadsheet – Word Processing – Data Management – Pictures and Presentations • Consumer Appliance – Video – Music – Entertainment – Games – Information Appliance – Communications and Talk – Photography