Hazard Specific Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracking Triggering Mechanisms for Soft-Sediment Deformation Structures in the Late Cretaceous Uberaba Formation, Bauru Basin, Brazil

SILEIR RA A D B E E G D E A O D L E O I G C I A O ARTICLE BJGEO S DOI: 10.1590/2317-4889202020190100 Brazilian Journal of Geology D ESDE 1946 Tracking triggering mechanisms for soft-sediment deformation structures in the Late Cretaceous Uberaba Formation, Bauru Basin, Brazil Luciano Alessandretti1* , Lucas Veríssimo Warren2 , Maurício Guerreiro Martinho dos Santos3 , Matheus Carvalho Virga1 Abstract Soft-sediment deformation (SSD) structures are widespread in the sedimentary record, and numerous triggering mechanisms can induce its development, including glaciation, earthquakes, overloading, ground-water fluctuations, and wave movement. The Late Cretaceous Ubera- ba Formation preserves SSD structures as small- and large-scale load casts and associated flame structures, pseudonodules, and convolute laminations observed in the contact of three well-defined intervals among fine- to coarse-grained lithic and conglomeratic sandstone with fine-grained arkose and mudstone beds. Based on the morphology of the SSD structures, sedimentary facies of the Uberaba Formation, and similarities with previous observations in the geological record and laboratory models, these features are assigned to liquefaction-fluidization processes as the major deformational mechanism triggered by seismic and aseismic agents. We propose that a deformation occurred just after the sedimentation triggered by seismic shock waves and overloading, induced by the sudden deposition of coarse-grained sandy debris on fine-grained sediments. Some of these structures can be classified as seismites, providing evidence of intraplate seismicity within the inner part of the South American Platform during the Late Cretaceous. This seismic activity is likely related to the uplift of the Alto Paranaíba High along reactivations of regional structures inherited from Proterozoic crustal discontinuities and coeval explosive magmatism of the Minas- Goiás Alkaline Province. -

Earthquake Measurements

EARTHQUAKE MEASUREMENTS The vibrations produced by earthquakes are detected, recorded, and measured by instruments call seismographs1. The zig-zag line made by a seismograph, called a "seismogram," reflects the changing intensity of the vibrations by responding to the motion of the ground surface beneath the instrument. From the data expressed in seismograms, scientists can determine the time, the epicenter, the focal depth, and the type of faulting of an earthquake and can estimate how much energy was released. Seismograph/Seismometer Earthquake recording instrument, seismograph has a base that sets firmly in the ground, and a heavy weight that hangs free2. When an earthquake causes the ground to shake, the base of the seismograph shakes too, but the hanging weight does not. Instead the spring or string that it is hanging from absorbs all the movement. The difference in position between the shaking part of the seismograph and the motionless part is Seismograph what is recorded. Measuring Size of Earthquakes The size of an earthquake depends on the size of the fault and the amount of slip on the fault, but that’s not something scientists can simply measure with a measuring tape since faults are many kilometers deep beneath the earth’s surface. They use the seismogram recordings made on the seismographs at the surface of the earth to determine how large the earthquake was. A short wiggly line that doesn’t wiggle very much means a small earthquake, and a long wiggly line that wiggles a lot means a large earthquake2. The length of the wiggle depends on the size of the fault, and the size of the wiggle depends on the amount of slip. -

Source Parameters of the 1933 Long Beach Earthquake

Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 81, No. 1, pp. 81- 98, February 1991 SOURCE PARAMETERS OF THE 1933 LONG BEACH EARTHQUAKE BY EGILL HAUKSSON AND SUSANNA GROSS ABSTRACT Regional seismographic network and teleseismic data for the 1933 (M L -- 6.3) Long Beach earthquake sequence have been analyzed, Both the teleseismic focal mechanism of the main shock and the distribution of the aftershocks are consistent with the event having occurred on the Newport-lnglewood fault. The focal mechanism had a strike of 315 °, dip of 80 o to the northeast, and rake of - 170°. Relocation of the foreshock- main shock-aftershock sequence using modern events as fixed refer- ence events, shows that the rupture initiated near the Huntington Beach-Newport Beach City boundary and extended unilaterally to the northwest to a distance of 13 to 16 km. The centroidal depth was 10 +_ 2 km. The total source duration was 5 sec, and the seismic moment was 5.102s dyne-cm, which corresponds to an energy magnitude of M w = 6.4. The source radius is estimated to have been 6.6 to 7.9 km, which corresponds to a Brune stress drop of 44 to 76 bars. Both the spatial distribution of aftershocks and inversion for the source time function suggest that the earthquake may have consisted of at least two subevents. When the slip estimate from the seismic moment of 85 to 120 cm is compared with the long-term geological slip rate of 0.1 to 1.0 mm I yr along the Newport-lnglewood fault, the 1933 earthquake has a repeat time on the order of a few thousand years. -

Validation of a Geospatial Liquefaction Model for Noncoastal Regions Including Nepal

USGS Award G16AP00014 Validation of a Geospatial Liquefaction Model for Noncoastal Regions Including Nepal Laurie G. Baise and Vahid Rashidian Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering Tufts University 200 College Ave Medford, MA 02155 617-627-2211 617-627-2994 [email protected] March 2016 – September 2017 Validation of a Geospatial Liquefaction Model for Noncoastal Regions Including Nepal Laurie G. Baise and Vahid Rashidian Civil and Environmental Engineering Department, Tufts University, Medford, MA. 02155 1. Abstract Soil liquefaction can lead to significant infrastructure damage after an earthquake due to lateral ground movements and vertical settlements. Regional liquefaction hazard maps are important in both planning for earthquake events and guiding relief efforts. New liquefaction hazard mapping techniques based on readily available geospatial data allow for an integration of liquefaction hazard in loss estimation platforms such as USGS’s PAGER system. The global geospatial liquefaction model (GGLM) proposed by Zhu et al. (2017) and recommended for global application results in a liquefaction probability that can be interpreted as liquefaction spatial extent (LSE). The model uses ShakeMap’s PGV, topography-based Vs30, distance to coast, distance to river and annual precipitation as explanatory variables. This model has been tested previously with a focus on coastal settings. In this paper, LSE maps have been generated for more than 50 earthquakes around the world in a wide range of setting to evaluate the generality and regional efficacy of the model. The model performance is evaluated through comparisons with field observation reports of liquefaction. In addition, an intensity score for easy reporting and comparison is generated for each earthquake through the summation of LSE values and compared with the liquefaction intensity inferred from the reconnaissance report. -

Chapter 4: Earthquakes and Human Activities

Chapter 4: Earthquakes and Human Activities Anatolian vs. San Andreas Fault (Figure 1) The Nature of Earthquakes ¾ Earthquakes occur along faults, or ruptures/fractures in the lithosphere (where movement takes place along the fracture). How and when does this fracturing take place? ¾ Elastic Rebound Theory (Harold Reid, 1906) ¾ Stress: force per unit area ¾ Strain: deformation Stress produces strain Types of Faults Two major groups with 2 subtypes each Group 1: Dip Slip Faults 1) Normal Stress type: 2) Reverse Stress type: Group 2: Strike Slip Faults Stress Type: 1) Right Lateral 2) Left Lateral Fault Nomenclature ¾ Movement along the fault blocks produces friction. We know this friction as an Earthquake. When Earthquakes occur, energy waves are released. These waves can be divided into two major groups, body waves and surface waves. Body waves- travel through the interior of the Earth 1) P Waves (Longitudinal Waves) 2) S Waves (Transverse Waves) Surface waves- travel near the surface 1) Love Waves 2) Raleigh Waves Locating the Epicenter ¾ Seismograph: instrument designed specifically to detect, measure, and record vibrations in the Earth’s crust. ¾ Seismogram: data recorded on paper (typically) from an earthquake event. ¾ Mapping epicenters has been characteristically done via triangulation. Earthquake Measurement ¾ First known earthquake measuring device- Chang Heng, China- 130 A.D. ¾ Modified Mercalli Scale – measures intensity of an earthquake o Utilizes roman numerals o Utilizes human perceptions (typically from questionnaires) o Isoseismals are generated from perceptions and then plotted on maps these plots can then be used to look for areas of weak soil or rock as well as areas of substandard building construction. -

STATE of OREGON DEPARTMENT of GEOLOGY and MINERAL INDUSTRIES • the Ore Bin •

/1:;f1;:z v 5(1;7'7:L..7 /.4'. ' iiiis <7 NOv i808 LIBRARY ."..„3 OREGON STATL .T. UNiVERStTY .6' Cr 4 r '..:- --" - -. Vol. 30, No. 10 October 1968 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES • The Ore Bin • Published Monthly By STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland, Oregon - 97201 Telephone: 226 - 2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 521 N. E. "E" Street Baker 97814 Grants Pass 97526 Subscription rate $1.00 per year. Available back issues 10 cents each. Second class postage paid at Portland, Oregon GOVERNING BOARD Frank C. McColloch, Chairman, Portland Fayette I. Bristol, Grants Pass Harold Banta, Baker STATE GEOLOGIST Hollis M. Dole GEOLOGISTS IN CHARGE OF FIELD OFFICES Norman S. Wagner, Baker Len Romp, Grants Pass Permission is granted to reprint information contained herein. Any credit given the State of Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries for compiling this information will be appreciated. State of Oregon The ORE BIN Department of Geology Volume 30, No. 10 and Mineral Industries October 1968 1069 State Office Bldg. Portland Oregon 97201 THE PORTLAND EARTHQUAKE OF MAY 13, 1968 AND EARTHQUAKE ENERGY RELEASE IN THE PORTLAND AREA By Richard Couch*, Stephen Johnson*, and John Gallagher* Introduction The earthquake of May 13, 1968 occurred at 10:52 a.m., PST. The earthquake epi- center was between the northeastern edge of the city of Portland and the Columbia River. The estimated magnitude is 3.8. This compares with the 3.7 magnitude shock of January 27, 1968 (Heinrichs and Pietralesa, 1968) but is smaller than the magni- tude 5 shock of November 5, 1962 Portland earthquake (Dehlinger and others, 1963). -

Earthquakes in Wyoming

111˚ Additional information on earthquakes, earthquake preparedness, 110˚ 104˚ Introduction 109˚ 108˚ 107˚ 106˚ 105˚ 45˚ 45˚ and earthquake response can be obtained from: Yellowstone Earthquakes are common in Wyoming. National WYOMING STATE Park Historically, earthquakes have occurred in Sheridan Wyoming State Geological Survey Crook GEOLOGICAL SURVEY every county in Wyoming over the past 120 P.O. Box 3008 Park Bighorn �� ���� years, with some causing significant damage. Laramie, WY 82071-3008 �� �� Lance Cook, State Geologist �� � Campbell Phone: (307) 766-2286 � Figure 1 shows the generalized distribution of Johnson 44˚ 44˚ historical earthquakes in Wyoming. Washakie Fax: (307) 766-2605 � � � Teton Weston � ���� � Email: [email protected] � �� The first recorded earthquake in the ������ �� Hot Springs [email protected] state occurred in the area now known as Agency Web: http://wsgsweb.uwyo.edu EARTHQUAKES IN Yellowstone National Park on July 20, 1871. Earthquake Web: http://www.wrds.uwyo.edu During the early geologic investigations of WYOMING Yellowstone, Ferdinand V. Hayden of the U.S. Fremont Natrona Niobrara 43˚ Converse 43˚ Wyoming Emergency Management Agency Geological Survey reported that “on the night 5500 Bishop Blvd. of the 20th of July, we experienced several se- Sublette Cheyenne, WY 82009-3320 vere shocks of an earthquake, and these were Phone: (307) 777-4900 felt by two other parties, fifteen or twenty-five Fax: (307) 635-6017 miles distant, on different sides of the lake.” Email: [email protected] Platte Goshen Yellowstone National Park is now known as 42˚ 42˚ Agency Web: http://132.133.10.9 one of the more seismically active areas in Lincoln FEMA Web: http://www.fema.gov the United States. -

On the Potential for Induced Seismicity at the Cavone Oilfield: Analysis of Geological and Geophysical Data, and Geomechanical Modeling

July, 2014 ON THE POTENTIAL FOR INDUCED SEISMICITY AT THE CAVONE OILFIELD: ANALYSIS OF GEOLOGICAL AND GEOPHYSICAL DATA, AND GEOMECHANICAL MODELING BY Luciana Astiz - University of California San Diego James H. Dieterich - University of California Riverside Cliff Frohlich - University of Texas at Austin Bradford H. Hager - Massachusetts Institute of Technology Ruben Juanes - Massachusetts Institute of Technology John H. Shaw –Harvard University 1 July, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ……………………………………………………….... 5 INTRODUCTION ………………………………………………………………….9 1. TECTONIC FRAMEWORK OF THE EMILIA-ROMAGNA REGION .................... 11 1.1 SEISMOTECTONIC SETTING ............................................................................................................................ 11 1.1.1 HISTORICAL SEISMICITY IN THE EMILIA‐ROMAGNA REGION .................................................................... 12 1.2 CAVONE STRUCTURE ....................................................................................................................................... 19 1.3 GEOLOGIC EVIDENCE FOR TECTONIC ACTIVITY OF STRUCTURES IN THE FERRARESE‐ROMAGNOLO ARC ..................................................................................................................... 24 1.4 SEISMOTECTONIC ANALYSIS .......................................................................................................................... 26 1.5 GPS CONSTRAINTS ON TECTONICS — PRE‐EARTHQUAKE REGIONAL DEFORMATION RATES ............ 30 1.6 CONCLUSIONS OF -

The Housing Market Impacts of Wastewater Injection Induced Seismicity Risk

The Housing Market Impacts of Wastewater Injection Induced Seismicity Risk Haiyan Liu Ph.D. Candidate Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Georgia [email protected] Susana Ferreira Associate Professor Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Georgia [email protected] Brady Brewer Assistant Professor Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics University of Georgia [email protected] Selected Paper prepared for presentation at the Agricultural & Applied Economics Association’s 2016 AAEA Annual Meeting, Boston, MA, July 31- August 2, 2016. Copyright 2016 by Haiyan Liu, Susana Ferreira, and Brady Brewer. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Abstract Using data from Oklahoma County, an area severely affected by the increased seismicity associated with injection wells, we recover hedonic estimates of property value impacts from nearby shale oil and gas development that vary with earthquake risk exposure. Results suggest that the 2011 Oklahoma earthquake in Prague, OK, and generally, earthquakes happening in the county and the state have enhanced the perception of risks associated with wastewater injection but not shale gas production. This risk perception is driven by injection wells within 2 km of the properties. Keywords: Earthquake, Wastewater Injection, Oil and Gas Production, Housing Market, Oklahoma JEL classification: L71, Q35, Q54, R31 1. Introduction The injection of fluids underground has been known to induce earthquakes since the mid-1960s (Healy et al. 1968; Raleigh et al. 1976). However, few cases were documented in the United States until 2009. -

Natural Hazards on Whidbey Island

Natural Hazards on Whidbey Island Protect and prepare your family and your home — a guide for surviving disasters caused by earthquakes, landslides, wildland fires, tsunamis, and windstorms Island County, Washington Department of Emergency Management Digital elevation map of Island County (Jessica Larson) ii Dealing with Natural Hazards on Whidbey Island This is a guide to the natural hazards that could affect you, your family, and your property. It offers a brief description of the ways you can prepare your home and family to survive disasters caused by earthquakes, landslides, wildland fires, tsunamis, and windstorms. Power outages caused by windstorms during the winter of 2006-2007 — as well as numerous other events in prior and more recent years — have made most residents of Whidbey Island amply aware of the difficulties of being without light, heat, water, and the ability to prepare meals or use health-related equipment. Although most of us have experienced being without power for less than a week, we have still been able to travel to a grocery, a hospital, or the mainland. Friends across the island could help each other. But what if there were a major natural disaster that cut off the island from the mainland and we were entirely on our own for two or three weeks? A truly large storm or an earthquake could destroy or damage docks at the Clinton and Coupeville ferries systems and seriously compromise footings of the Deception Pass bridge, disrupting delivery of food, water, fuel, emergency services, and many other vitally necessary elements of our Island life. These realities are even more evident recently as we have had record rains, experienced more landslides, and observed the damage suffered by the islands of New Zealand and Japan. -

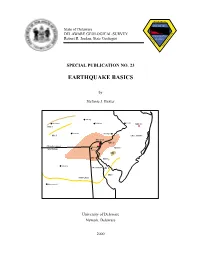

Earthquake Basics

RESEARCH DELAWARE State of Delaware DELAWARE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SERVICEGEOLOGICAL Robert R. Jordan, State Geologist SURVEY EXPLORATION SPECIAL PUBLICATION NO. 23 EARTHQUAKE BASICS by Stefanie J. Baxter University of Delaware Newark, Delaware 2000 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION . 1 EARTHQUAKE BASICS What Causes Earthquakes? . 1 Seismic Waves . 2 Faults . 4 Measuring Earthquakes-Magnitude and Intensity . 4 Recording Earthquakes . 8 REFERENCES CITED . 10 GLOSSARY . 11 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Major tectonic plates, midocean ridges, and trenches . 2 2. Ground motion near the surface of the earth produced by four types of earthquake waves . 3 3. Three primary types of fault motion . 4 4. Duration Magnitude for Delaware Geological Survey seismic station (NED) located near Newark, Delaware . 6 5. Contoured intensity map of felt reports received after February 1973 earthquake in northern Delaware . 8 6. Model of earliest seismoscope invented in 132 A. D. 9 TABLES Table Page 1. The 15 largest earthquakes in the United States . 5 2. The 15 largest earthquakes in the contiguous United States . 5 3. Comparison of magnitude, intensity, and energy equivalent for earthquakes . 7 NOTE: Definition of words in italics are found in the glossary. EARTHQUAKE BASICS Stefanie J. Baxter INTRODUCTION Every year approximately 3,000,000 earthquakes occur worldwide. Ninety eight percent of them are less than a mag- nitude 3. Fewer than 20 earthquakes occur each year, on average, that are considered major (magnitude 7.0 – 7.9) or great (magnitude 8 and greater). During the 1990s the United States experienced approximately 28,000 earthquakes; nine were con- sidered major and occurred in either Alaska or California (Source: U.S. -

Understanding the Richter Magnitude Scale for Earthquakes the Richter Magnitude Scale Was Developed in the 1930S and Is One of T

Understanding The Richter Magnitude Scale For Earthquakes The Richter magnitude scale was developed in the 1930s and is one of the most widely used forms of measurement for earthquake size. It is a base-10 logarithmic scale. This means that it measures an earthquake based on the logarithm of the seismic wave amplitude ratio in contrast to minor arbitrary amplitude. When measured using a seismometer, an earthquake rated as 5.0 on the Richter scale has an amplitude that is 10 times more powerful than a 4.0 earthquake occurring at the same distance. This equals a release of energy that is 31.6 times greater than the weaker earthquake. The Richter scale is still used by some. However, it was officially replaced in the United States in the 1970s by the moment magnitude scale, which is used by the United States Geological Survey for measuring and reporting quakes. The Richter scale was developed especially for Southern California where most of the activity took place then. With the new instrument, scientists were able to measure the quakes in a more specific way. However, the frequent earthquakes saturated the scale, which made it unable to accurately record all events and high values. This is what led to its replacement in the 1970s. Numerical values between the modern moment magnitude scale and the Richter scale are similar. Also, the USGS maintains that any quake classified as a 5.0 or higher is considered a major risk. Both the MMS and Richter scales measure an earthquake's released energy. The Mercalli intensity scale measures the effects of earthquakes.