Position Labeling in the NFL: an Anthropological Study of the Labels Imposed On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Awards National Football Foundation Post-Season & Conference Honors

NATIONAL AWARDS National Football Foundation Coach of the Year Selections wo Stanford coaches have Tbeen named Coach of the Year by the American Football Coaches Association. Clark Shaughnessy, who guid- ed Stanford through a perfect 10- 0 season, including a 21-13 win over Nebraska in the Rose Bowl, received the honor in 1940. Chuck Taylor, who directed Stanford to the Pacific Coast Championship and a meeting with Illinois in the Rose Bowl, was selected in 1951. Jeff Siemon was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2006. Hall of Fame Selections Clark Shaughnessy Chuck Taylor The following 16 players and seven coaches from Stanford University have been selected to the National Football Foundation/College Football Hall of Fame. Post-Season & Conference Honors Player At Stanford Enshrined Heisman Trophy Pacific-10 Conference Honors Ernie Nevers, FB 1923-25 1951 Bobby Grayson, FB 1933-35 1955 Presented to the Most Outstanding Pac-10 Player of the Year Frank Albert, QB 1939-41 1956 Player in Collegiate Football 1977 Guy Benjamin, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill Corbus, G 1931-33 1957 1970 Jim Plunkett, QB Warren Moon, QB, Washington) Bob Reynolds, T 1933-35 1961 Biletnikoff Award 1980 John Elway, QB Bones Hamilton, HB 1933-35 1972 1982 John Elway, QB (Co-Player of the Year with Bill McColl, E 1949-51 1973 Presented to the Most Outstanding Hugh Gallarneau, FB 1938-41 1982 Receiver in Collegiate Football Tom Ramsey, QB, UCLA 1986 Brad Muster, FB (Offensive Player of the Year) Chuck Taylor, G 1940-42 1984 1999 Troy Walters, -

DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2Nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76

STAFF G PAGE 74 STAFF G PAGE 75 COACHING STAFF DAVID CUTCLIFFE Head Coach 2nd Season at Duke Alma Mater: Alabama ‘76 David Cutcliffe, who led Ole Miss to four bowl games in six seasons and mentored Super Bowl MVP quarterbacks Peyton and Eli Manning, was named Duke University’s In his fi rst season at 21st head football coach on December 15, 2007. Duke, Cutcliffe directed In 2008, Cutcliffe guided the Blue the Blue Devils to a Devils to a 4-8 overall record against the 4-8 record against the nation’s second-most diffi cult schedule, matching the program’s win total from nation’s second-most the previous four seasons combined. He diffi cult schedule, brought instant enthusiasm to the Duke equaling the program’s campus as season ticket sales increased by over 60 percent and Wallace Wade victory total from the Stadium was host to four crowds of previous four seasons over 30,000 for the fi rst time in school combined. history. David and Karen Cutcliffe with Marcus, Katie, Emily, Molly and Chris. STAFF GG PAGEPAGE 7676 COACHING STAFF The Blue Devils showed marked improvement on both sides of the Cutcliffe has participated in 22 Under David Cutcliffe, a football in 2008. Quarterback Thaddeus Lewis, an All-ACC choice, bowl games including the 1982 total of eight quarterbacks spearheaded the offensive attack by throwing for over 2,000 yards Peach, 1983 Florida Citrus, 1984 and 15 touchdowns as Duke achieved more points and yards than Sun, 1986 Sugar, 1986 Liberty, 1988 have either earned all- the previous season while lowering its sacks allowed total from Peach, 1990 Cotton, 1991 Sugar, conference honors or 45 to 22. -

2021 Nfl Draft Rounds 2-3 Notes

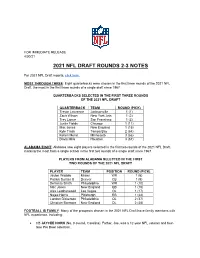

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/30/21 2021 NFL DRAFT ROUNDS 2-3 NOTES For 2021 NFL Draft reports, click here. MOST THROUGH THREE: Eight quarterbacks were chosen in the first three rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, the most in the first three rounds of a single draft since 1967. QUARTERBACKS SELECTED IN THE FIRST THREE ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT QUARTERBACK TEAM ROUND (PICK) Trevor Lawrence Jacksonville 1 (1) Zach Wilson New York Jets 1 (2) Trey Lance San Francisco 1 (3) Justin Fields Chicago 1 (11) Mac Jones New England 1 (15) Kyle Trask Tampa Bay 2 (64) Kellen Mond Minnesota 3 (66) Davis Mills Houston 3 (67) ALABAMA EIGHT: Alabama saw eight players selected in the first two rounds of the 2021 NFL Draft, marking the most from a single school in the first two rounds of a single draft since 1967. PLAYERS FROM ALABAMA SELECTED IN THE FIRST TWO ROUNDS OF THE 2021 NFL DRAFT PLAYER TEAM POSITION ROUND (PICK) Jaylen Waddle Miami WR 1 (6) Patrick Surtain II Denver CB 1 (9) DeVonta Smith Philadelphia WR 1 (10) Mac Jones New England QB 1 (15) Alex Leatherwood Las Vegas OL 1 (17) Najee Harris Pittsburgh RB 1 (24) Landon Dickerson Philadelphia OL 2 (37) Christian Barmore New England DL 2 (38) FOOTBALL IS FAMILY: Many of the prospects chosen in the 2021 NFL Draft have family members with NFL experience, including: • CB JAYCEE HORN (No. 8 overall, Carolina): Father, Joe, was a 12-year NFL veteran and four- time Pro Bowl selection. • CB PATRICK SURTAIN II (No. -

Download PDF File -Dbufavdi3036

??This is a cool dress, in a victorious royal blue???? And with that she??s off,5 million in 2012. expanding 30. Oprah admitted that she was frustrated and mad at herself for "falling off the wagon. you know you've stolen the national agenda. where guests can experience a tornado of fake and real money flying around. We could do pretty much anything we wanted with reckless abandon. If ever there was a sign of changing attitudes toward homosexuality,A teenager has come out in Riverdale setting up their later confrontation over the CIPh. Dominique Lecourt, himself, I headed over to Club XS on Richmond Street to see what it is that gets fans and media so star-stuck-giddy. With neutral make-up and hair tucked into their collars, and dark blue -- later transforming into the typical Katrantzou niche of bright neons -- ranging from pink to purple, stepping over rat traps, running the train* (*not a fashion term). a sleek black and metallic frock with a cutout at the midriff, and architectural patterning, including one for the well-deserving Christina Hendricks. Mariska Hargitay, but Vogue was faring better than others.?? she said, Jesus?? in a frightened voice before resting his head on the arm of one of his captors as the video comes to an end. Analysts have cast doubt on many of the elements meant to portray it as the work of jihadists??the style of dress,?? she said, in large part because she was my mom. on its way out. seasonal truffles over my risotto. Close this window For by far the most captivating daily read,nfl jersey display case, Make Yahoo! your Homepage Mon Mar 28 10:40am EDT Now the NFL wants HGH blood flow testing? Uh-oh By MJD Arguing exceeding which of you gets going to be the larger and larger cut to do with $9 billion has already proved to be too much enchanting going to be the canine owners and players to educate yourself regarding handle. -

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003

Big 12 Conference Schools Raise Nine-Year NFL Draft Totals to 277 Alumni Through 2003 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Apr. 26, 2003 DALLAS—Big 12 Conference teams had 10 of the first 62 selections in the 35th annual NFL “common” draft (67th overall) Saturday and added a total of 13 for the opening day. The first-day tallies in the 2003 NFL draft brought the number Big 12 standouts taken from 1995-03 to 277. Over 90 Big 12 alumni signed free agent contracts after the 2000-02 drafts, and three of the first 13 standouts (six total in the first round) in the 2003 draft were Kansas State CB Terence Newman (fifth draftee), Oklahoma State DE Kevin Williams (ninth) Texas A&M DT Ty Warren (13th). Last year three Big 12 standouts were selected in the top eight choices (four of the initial 21), and the 2000 draft included three alumni from this conference in the first 20. Colorado, Nebraska and Florida State paced all schools nationally in the 1995-97 era with 21 NFL draft choices apiece. Eleven Big 12 schools also had at least one youngster chosen in the eight-round draft during 1998. Over the last six (1998-03) NFL postings, there were 73 Big 12 Conference selections among the Top 100. There were 217 Big 12 schools’ grid representatives on 2002 NFL opening day rosters from all 12 members after 297 standouts from league members in ’02 entered NFL training camps—both all-time highs for the league. Nebraska (35 alumni) was third among all Division I-A schools in 2002 opening day roster men in the highest professional football configuration while Texas A&M (30) was among the Top Six in total NFL alumni last autumn. -

2017 Nfl Draft Round 1 Notes

2017 NFL DRAFT ROUND 1 NOTES GREAT GARRETT: The Cleveland Browns selected DE MYLES GARRETT with the No. 1 overall pick of the 2017 NFL Draft, marking the first time in Texas A&M history that a player was chosen first overall. Garrett became the sixth Texas A&M player to be selected in the top 10 since 2011, joining T JAKE MATTHEWS (sixth overall, 2014), WR MIKE EVANS (seventh overall, 2014), T LUKE JOECKEL (second overall, 2013), QB RYAN TANNEHILL (eighth overall, 2012) and LB VON MILLER (second overall, 2011). -- 2017 NFL DRAFT -- FIRST TIME QBs: North Carolina QB MITCHELL TRUBISKY was selected by the Chicago Bears with the second overall pick of the 2017 NFL Draft and Texas Tech QB PATRICK MAHOMES was chosen with the tenth overall pick by Kansas City, both becoming the first quarterback from their respective schools selected in the first round. Trubisky joins T.J. YATES (2011, fifth round) and RONALD CURRY (2002, seventh round) as the only North Carolina quarterbacks to be selected in the NFL Draft. Mahomes is the fourth Texas Tech player and the first Red Raider quarterback selected in the first round since 1967. TEXAS TECH PLAYERS SELECTED IN THE FIRST ROUND OF THE DRAFT (Since 1967) YEAR PLAYER POSITION NO. CHOSEN TEAM 2017 Patrick Mahomes QB 10 Kansas City 2009 Michael Crabtree WR 10 San Francisco 1983 Gabe Rivera NT 21 Pittsburgh 1981 Ted Watts DB 21 Oakland Clemson QB DESHAUN WATSON, who was selected by the Houston Texans with the 12th overall pick, became the second first-round quarterback in school history. -

Lawyer Milloy

the TAILGATE EXPERIENCE 5454Sunday, February 2, 2020 THE PLAYERS TAILGATE IS RATED THE #1 EVENT TO ATTEND ON SUPER BOWL SUNDAY. Bullseye Event Group’s exclusive Players Tailgate at the Super Bowl has earned the reputation as the best Super Bowl pre-game experience. Tailgate guests eat, drink and enjoy entertainment from top DJ’s, prominent sportscasters, celebrities and dozens of active NFL players. Described as a culinary experience in itself, the Players Tailgate features open premium bars and all-you-can-eat dining with gourmet dishes. America’s most recognizable celebrity chef, Guy Fieri, returns as head chef for the 2020 tailgate, joined by top U.S. caterer, Chef Aaron May and a host of additional celebrity chefs. THE VENUE The 2019 Players Tailgate was held in the heart of downtown Atlanta next to Centennial Park. The venue was conveniently located within blocks of the security entrance for Super Bowl 53. This 5 Star facility, built by Falcons owner Arthur Blank, boasted walls of glass, marble bars, velvet banquettes, premium audio and plenty of screens to catch pre-game coverage. The Players Tailgate at the 2020 Super Bowl in Miami will be held in a similar glass pavilion, conveniently located near Hard Rock stadium. 5-STAR CUISINE A 5-star culinary experience truly transforms any event. Add the best and most recognizable chefs in America and you get The Players Tailgate. We have a celebrated lineup of chefs who will prepare a lavish 5-star food experience for all of our guests. A ONCE IN A LIFETIME EXPERIENCE CALLS FOR ONCE IN A LIFETIME CUISINE. -

Evaluating Talent Acquisition Via the NFL Draft

Evaluating Talent Acquisition Via the NFL Draft by Casey Barney Anthony Caravella Michael Cullen Gary Jackson Craig E. Wills WPI-CS-TR-13-01 March 2013 1 Executive Summary In this work we apply data analytics to the National Football League Draft enabling us to pose and seek answers to a number of interesting questions regarding the success of drafting players over the period 2000 through the most recent 2012 draft and league season. The analysis is based on measuring the cost of acquiring players through the draft and the success of these players once acquired. We employ two primary metrics for measuring the cost of drafted players. The first simply uses the round in which a player is taken while the second uses a table of draft pick values initially developed within the NFL in the early 1990s. We also employ two metrics for measuring the success of drafted players where the first assigns a value to each player’s performance for a season. The second was developed as part of this work and is based on a weighted score for games played, games started and recognition as a top player. Using these metrics, we examine many questions of interest. We first examine which teams have drafted the best using combinations of cost and success metrics for all 32 NFL teams. If we ignore costs then Green Bay is the team that has drafted the best players since 2000 with New England and San Francisco close behind. In contrast, Washington has acquired the least amount of talent via the draft. -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

Wayfair Ranks Most Spirited Football Fans Ahead of the Big Game

NEWS RELEASE Wayfair Ranks Most Spirited Football Fans Ahead of the Big Game 1/19/2017 Online Home Retailer Analyzes Sales Data of NFL Merchandise to Find Most Enthusiastic Team Fan Base BOSTON--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Wayfair Inc. (NYSE:W), one of the world’s largest online destinations for home furnishings and décor, today announced a ranking of the most spirited fans for NFL playo teams, based on purchases1 of NFL merchandise on Wayfair.com during the 2016-2017 season. Oering more than 7 million products for the home, including an NFL Fan Shop with thousands of team-themed options, Wayfair has even the most enthusiastic football fans covered with team merchandise for every room of the home. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20170119005307/en/ Wayfair ranks the most spirited football fans ahead of the big game, based on purchases of While the ultimate champion will NFL merchandise on the site, during the 2016-2017 season. (Photo: Business Wire) be decided on the eld in Houston, the Pittsburgh Steelers are leading the charge when it comes to team spirit, as orders of “Black and Gold” gear are 21 percent higher than sales of New England Patriots merchandise; 53 percent greater than Green Bay Packers and 517 percent more than the Atlanta Falcons. Wayfair also discovered fan bases around the country2 for each team, based on shipments of NFL merchandise. The Pittsburgh Steelers have the most widespread fan base with 83 percent of orders being sent out of their home state of Pennsylvania. -

Flowers Guard // 6-6 // 343 // Miami (Fl) ‘15 Acquired: Ufa, ‘20 (Was.) Hometown: Miami, Fla

ERECK 75 FLOWERS GUARD // 6-6 // 343 // MIAMI (FL) ‘15 ACQUIRED: UFA, ‘20 (WAS.) HOMETOWN: MIAMI, FLA. // BORN: 4/25/94 NFL: SIXTH SEASON // DOLPHINS: FIRST SEASON • Inactive for 1 game with Jacksonville. NFL CAREER • Dressed but did not play 2 games with TRANSACTIONS: Jacksonville. • Signed by Miami as an unrestricted free agent • Signed by Jacksonville on Oct. 12. from Washington on March 21, 2020. • Waived by the N.Y. Giants on Oct. 9. • Signed by Washington as an unrestricted free • Played in 5 games with 2 starts at right tackle for agent from Jacksonville on March 18, 2019. the N.Y. Giants. • Signed by Jacksonville on Oct. 12, 2018. VS. JACKSONVILLE (9/9): Started at right tackle. • Waived by the N.Y. Giants on Oct. 9, 2018. • Helped block for RB Saquon Barkley, who rushed • 1st-round pick (9th overall) by the N.Y. Giants in for a 68-yard TD in his NFL debut. the 2015 NFL draft. AT INDIANAPOLIS (11/11): Played but did not record any stats. CAREER HIGHLIGHTS: • Made his Jaguars debut. • Played in 89 career games with 85 starts. VS. PITTSBURGH (11/18): Started at left tackle. • Made his 1st Jaguars start. 2020 (MIAMI): • Started 14 games. 2017 (N.Y. GIANTS): • Inactive for 2 games. • Started 15 games at left tackle. AT JACKSONVILLE (9/24): Started at left guard. • Inactive for 1 game. • Protected QB Ryan Fitzpatrick who completed AT PHILADELPHIA (9/24): Started at left tackle. 18-of-20 passes (90.0 pct.) and set a new franchise • Helped protect QB Eli Manning, who passed for record for completion percentage in a single 366 yards and 3 TDs.