A Review of Research on Sexual Violence in Audio-Visual Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vaitoskirjascientific MASCULINITY and NATIONAL IMAGES IN

Faculty of Arts University of Helsinki, Finland SCIENTIFIC MASCULINITY AND NATIONAL IMAGES IN JAPANESE SPECULATIVE CINEMA Leena Eerolainen DOCTORAL DISSERTATION To be presented for public discussion with the permission of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Helsinki, in Room 230, Aurora Building, on the 20th of August, 2020 at 14 o’clock. Helsinki 2020 Supervisors Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Bart Gaens, University of Helsinki, Finland Pre-examiners Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Rikke Schubart, University of Southern Denmark, Denmark Opponent Dolores Martinez, SOAS, University of London, UK Custos Henry Bacon, University of Helsinki, Finland Copyright © 2020 Leena Eerolainen ISBN 978-951-51-6273-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-951-51-6274-8 (PDF) Helsinki: Unigrafia, 2020 The Faculty of Arts uses the Urkund system (plagiarism recognition) to examine all doctoral dissertations. ABSTRACT Science and technology have been paramount features of any modernized nation. In Japan they played an important role in the modernization and militarization of the nation, as well as its democratization and subsequent economic growth. Science and technology highlight the promises of a better tomorrow and future utopia, but their application can also present ethical issues. In fiction, they have historically played a significant role. Fictions of science continue to exert power via important multimedia platforms for considerations of the role of science and technology in our world. And, because of their importance for the development, ideologies and policies of any nation, these considerations can be correlated with the deliberation of the role of a nation in the world, including its internal and external images and imaginings. -

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Gender and the Family in Contemporary Chinese-Language Film Remakes

Gender and the family in contemporary Chinese-language film remakes Sarah Woodland BBusMan., BA (Hons) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2016 School of Languages and Cultures 1 Abstract This thesis argues that cinematic remakes in the Chinese cultural context are a far more complex phenomenon than adaptive translation between disparate cultures. While early work conducted on French cinema and recent work on Chinese-language remakes by scholars including Li, Chan and Wang focused primarily on issues of intercultural difference, this thesis looks not only at remaking across cultures, but also at intracultural remakes. In doing so, it moves beyond questions of cultural politics, taking full advantage of the unique opportunity provided by remakes to compare and contrast two versions of the same narrative, and investigates more broadly at the many reasons why changes between a source film and remake might occur. Using gender as a lens through which these changes can be observed, this thesis conducts a comparative analysis of two pairs of intercultural and two pairs of intracultural films, each chapter highlighting a different dimension of remakes, and illustrating how changes in gender representations can be reflective not just of differences in attitudes towards gender across cultures, but also of broader concerns relating to culture, genre, auteurism, politics and temporality. The thesis endeavours to investigate the complexities of remaking processes in a Chinese-language cinematic context, with a view to exploring the ways in which remakes might reflect different perspectives on Chinese society more broadly, through their ability to compel the viewer to reflect not only on the past, by virtue of the relationship with a source text, but also on the present, through the way in which the remake reshapes this text to address its audience. -

Read an Excerpt

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Unseen Femininity: Women in Japanese New Wave Cinema

UNSEEN FEMININITY: WOMEN IN JAPANESE NEW WAVE CINEMA by Candice N. Wilson B.A. in English/Film, Middlebury College, Middlebury, 2001 M.A. in Cinema Studies, New York University, New York, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in English/Film Studies University of Pittsburgh 2015 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH KENNETH P. DIETRICH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Candice N. Wilson It was defended on April 27, 2015 and approved by Marcia Landy, Distinguished Professor, Film Studies Program Neepa Majumdar, Associate Professor, Film Studies Program Nancy Condee, Director, Graduate Studies (Slavic) and Global Studies (UCIS), Slavic Languages and Literatures Dissertation Advisor: Adam Lowenstein, Director, Film Studies Program ii Copyright © by Candice N. Wilson 2015 iii UNSEEN FEMININITY: WOMEN IN JAPANESE NEW WAVE CINEMA Candice N. Wilson, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2015 During the mid-1950s to the early 1970s a subversive cinema, known as the Japanese New Wave, arose in Japan. This dissertation challenges critical trends that use French New Wave cinema and the oeuvre of Oshima Nagisa as templates to construct Japanese New Wave cinema as largely male-centered and avant-garde in its formal aesthetics. I argue instead for the centrality of the erotic woman to a questioning of national and postwar identity in Japan, and for the importance of popular cinema to an understanding of this New Wave movement. In short, this study aims to break new ground in Japanese New Wave scholarship by focusing on issues of gender and popular aesthetics. -

Horror Genre in National Cinemas of East Slavic Countries

Studia Filmoznawcze 35 Wroc³aw 2014 Volha Isakava University of Ottawa, Canada HORROR GENRE IN NATIONAL CINEMAS OF EAST SLAVIC COUNTRIES In this essay I would like to outline several tendencies one can observe in con- temporary horror fi lms from three former Soviet republics: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. These observations are meant to chart the recent (2000-onwards) de- velopment of horror as a genre of mainstream cinema, and what cultural, social and political forces shape its development. Horror fi lm is of particular interest to me because it is a popular genre known for a long and interesting history in American cinema. In addition, horror is one of transnational genres that infuse Hollywood formula with particularities of national cinematic traditions (most no- table example is East Asian horror cinema, namely “J-horror,” Japanese horror). To understand the peculiarity of the newly emerged horror genre in the cinemas of East Slavic countries, I propose two venues of exploration, or two perspectives. The fi rst one could be called the global perspective: horror fi lm, as it exists today in post-Soviet space, is profoundly infl uenced by Hollywood. Domestic produc- tions compete with American fi lms at the box offi ce and strive to emulate genre structures of Hollywood to attract viewers, whose tastes are largely shaped by American fi lms. This is especially true for horror, which has almost no reference point in national cinematic traditions in question. The second vantage point is local: the local specifi city of these horror narratives, how the fi lms refl ect their own cultural condition, shaped by today’s globalized cinema market, Hollywood hegemony and local sensibilities of distinct cinematic and pop-culture traditions. -

The Final Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016 Lauren Cupp Scripps College Recommended Citation Cupp, Lauren, "The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 958. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/958 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FINAL GIRL GROWN UP: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN HORROR FILMS FROM 1978-2016 by LAUREN J. CUPP SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TRAN PROFESSOR MACKO DECEMBER 9, 2016 Cupp 2 I was a highly sensitive kid growing up. I was terrified of any horror movie I saw in the video store, I refused to dress up as anything but a Disney princess for Halloween, and to this day I hate haunted houses. I never took an interest in horror until I took a class abroad in London about horror films, and what peaked my interest is that horror is much more than a few cheap jump scares in a ghost movie. Horror films serve as an exploration into our deepest physical and psychological fears and boundaries, not only on a personal level, but also within our culture. Of course cultures shift focus depending on the decade, and horror films in the United States in particular reflect this change, whether the monsters were ghosts, vampires, zombies, or aliens. -

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes ...........................................Christopher J. Garcia ....................................................................................................3 Letters of Comment .....................................Jean Martin and Chris Garcia ....................................................................................4-6 Editorial .......................................................Jean Martin ................................................................................................................... 7 Ghosts and Surreal Art in Portland ...............Jean Marin ................................Photos Jean Martin ................................................8-11 Nemo Gould Sculptures ...............................Espana Sheriff ...........................Photos from www.nemomatic.com ......................12-13 Reading at Intersection for the Arts ..............Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................14-15 Klingon Celebration .....................................Jean Marin ................................Photos by Jean Martin .........................................16-21 BASFA Minutes ..........................................................................................................................................................................22-24 -

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย

Women and Yaoi Fan Creative Work เพศหญิงและงานสร้างสรรค์แนวยาโอย Proud Arunrangsiwed1 พราว อรุณรังสีเวช Nititorn Ounpipat2 นิติธร อุ้นพิพัฒน์ Krisana Cheachainart3 Article History กฤษณะ เชื้อชัยนาท Received: May 12, 2018 Revised: November 26, 2018 Accepted: November 27, 2018 Abstract Slash and Yaoi are types of creative works with homosexual relationship between male characters. Most of their audiences are female. Using textual analysis, this paper aims to identify the reasons that these female media consumers and female fan creators are attracted to Slash and Yaoi. The first author, as a prior Slash fan creator, also provides part of experiences to describe the themes found in existing fan studies. Five themes, both to confirm and to describe this phenomenon are (1) pleasure of same-sex relationship exposure, (2) homosexual marketing, (3) the erotic fantasy, (4) gender discrimination in primacy text, and (5) the need of equality in romantic relationship. This could be concluded that these female fans temporarily identify with a male character to have erotic interaction with another male one in Slash narrative. A reason that female fans need to imagine themselves as a male character, not a female one, is that lack of mainstream media consists of female characters with a leading role, besides the romance genre. However, the need of gender equality, as the reason of female fans who consume Slash text, might be the belief of fan scholars that could be applied in only some contexts. Keywords: Slash, Yaoi, Fan Creation, Gender 1Faculty of -

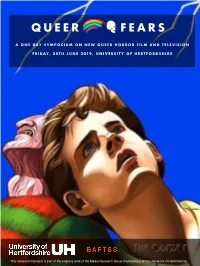

Queer Fears Programme Final 2019

QUEER FEARS A ONE DAY SYMPOSIUM ON NEW QUEER HORROR FILM AND TELEVISION FRIDAY, 28TH JUNE 2019, UNIVERSITY OF HERTFORDSHIRE This symposium/project is part of the ongoing work of the Media Research Group (Humanities) at the University of Hertfordshire. SYMPOSIUM PROGRAMME 9am Registration (Cinema Foyer, coffee and tea provided) 10am Conference Opening Address and Welcome (Cinema Auditorium downstairs) 10.15-11.45pm Panel 1: In and Out of the Closet - (Chair: Darren Elliott-Smith, University of Herts) Chris Lloyd (University of Hertfordshire) – American Horror Story – Queer Fears in the USA. Tim Stafford (Independent Scholar) – All’s Queer in Love and War-lock: The Problematic Queer Space in The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina The Teenage Witch. Ben Wheeler (University of Hertfordshire) - Losing Boys, Falling Down, Gaining Nipples: The Queer Fears of Joel Schumacher. 11.45-12.00pm Coffee Break 12.00-1.30pm Panel 2: Queer Performative Horror - (Chair: Laura Mee, University of Hertfordshire) Valeria Lindvall (University of Gothenburg, Sweden) – Dragula and Queer Performance. Daniel Sheppard (University of East Anglia) – The Babadook and New Realisations of the Monster Queer. Lexi Turner (Cornell University) – The Dance of An Other – Queer Dance as Ritual in Suspiria and Climax. 1.30-2.15pm Lunch and Refreshments (Cinema Foyer Downstairs) 2.15 - 3.45pm Panel 3: Consuming Queerness and Other Gross Tales… (Chair: Christopher Lloyd, University of Hertfordshire) Robyn Ollett (University of Teeside) - What do you eat? Queering the Cannibal in Ducourneau’s RAW. Eddie Falvey (University of Exeter) - Conspicuous Corporeality - Monstrousness as Queer in Ducourneau’s RAW. Laura Mee (University of Hertfordshire) - Sick Girls, Bloodhound Bitches, Feral Females and Weirdos: Queer Women in the films of Lucky McKee 3.45 – 4.00pm Coffee Break 4.00 - 5.30pm Panel 4: Frightfully Problematic Queerness (Chair: Agustin Rico- Albero, University of Hertfordshire) Siobhan O’Reilly (University of Hertfordshire) - Queer Horror and Transphobia.