A Historical Approach to the Slasher Film Below Halloween (1978)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Halloween Should Be Spooky, Not Scary! Governor Cuomo Asks for Your Help to Make Sure Everyone Has a Healthy and Safe Halloween

Halloween should be spooky, not scary! Governor Cuomo asks for your help to make sure everyone has a healthy and safe Halloween. Halloween celebrations and activities, including trick-or-treating, can be filled with fun, but must be done in a safe way to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The best way to celebrate Halloween this year is to have fun with the people who live in your household. Decorating your house or apartment, decorating and carving pumpkins, playing Halloween-themed games, watching spooky movies, and trick-or-treating through your house or in a backyard scavenger hunt are all fun and healthy ways to celebrate during this time. Creative ways to celebrate more safely: • Organize a virtual Halloween costume party with costumes and games. • Have a neighborhood car parade or vehicle caravan where families show off their costumes while staying socially distanced and remaining in their cars. • In cities or apartment buildings, communities can come together to trick-or-treat around the block or other outdoor spaces so kids and families aren’t tempted to trick-or-treat inside – building residents & businesses can contribute treats that are individually wrapped and placed on a table(s) outside of the front door of the building, or in the other outdoor space for grab and go trick-or-treating. • Make this year even more special and consider non-candy Halloween treats that your trick- or-treaters will love, such as spooky or glittery stickers, magnets, temporary tattoos, pencils/ erasers, bookmarks, glow sticks, or mini notepads. • Create a home or neighborhood scavenger hunt where parents or guardians give their kids candy when they find each “clue.” • Go all out to decorate your house this year – have a neighborhood contest for the best decorated house. -

Running Head: HORROR and HALLOWEEN 1 Horror, Halloween

Running head: HORROR AND HALLOWEEN 1 Horror, Halloween, and Hegemony: A Psychoanalytical Profile and Empirical Gender Study of the “Final Girls” in the Halloween Franchise Tabatha Lehmann Department of Psychology Dr. Patrick L. Smith Thesis for completion of the Honors Program Florida Southern College April 29, 2021 HORROR AND HALLOWEEN 2 Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine how the perceptions of femininity have changed throughout time. This can be made possible through a psychoanalysis of the main character of Halloween, Laurie Strode, and other female characters from the original Halloween film released in 1978 to the more recent sequel announced in 2018. Previous research has shown that horror films from the slasher genre in the 1970s and 1980s have historically depicted men and women as displaying behaviors that are largely indicative of their gender stereotypes (Clover, 1997; Connelly, 2007). Men are typically the antagonists of these films, and display perceptible aggression, authority, and physical strength; on the contrary, women generally play the victims, and are usually portrayed as weaker, more subordinate, and often in a role that perpetuates the classic stereotypes of women as more submissive to males and as being more emotionally stricken during perceived traumatic events (Clover, 1997; Lizardi, 2010; Rieser, 2001; Williams, 1991). Research has also shown that the “Final Girl” in horror films—the last girl left alive at the end of the movie—has been depicted as conventionally less feminine compared to other female characters featured in these films (De Muzio, 2006; Lizardi, 2010). This study found that Laurie Strode in 1978 was more highly rated on a gender role scale for feminine characteristics, while Laurie Strode in 2018 was found to have had significantly higher rating for masculine word descriptors than feminine. -

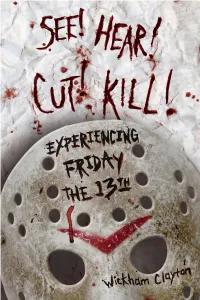

Read an Excerpt

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011)

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Film Review Aggregators and Their ffecE t on Sustained Box Officee P rformance Nicholas Krishnamurthy Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Krishnamurthy, Nicholas, "Film Review Aggregators and Their Effect on Sustained Box Office Performance" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 291. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/291 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE FILM REVIEW AGGREGATORS AND THEIR EFFECT ON SUSTAINED BOX OFFICE PERFORMANCE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR DARREN FILSON AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY NICHOLAS KRISHNAMURTHY FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL / 2011 November 28, 2011 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my parents for their constant support of my academic and career endeavors, my brother for his advice throughout college, and my friends for always helping to keep things in perspective. I would also like to thank Professor Filson for his help and support during the development and execution of this thesis. Abstract This thesis will discuss the emerging influence of film review aggregators and their effect on the changing landscape for reviews in the film industry. Specifically, this study will look at the top 150 domestic grossing films of 2010 to empirically study the effects of two specific review aggregators. A time-delayed approach to regression analysis is used to measure the influencing effects of these aggregators in the long run. Subsequently, other factors crucial to predicting film success are also analyzed in the context of sustained earnings. -

A Cinema of Confrontation

A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by COURT MONTGOMERY Dr. Nancy West, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR presented by Court Montgomery, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________ Professor Nancy West _________________________________ Professor Joanna Hearne _________________________________ Professor Roger F. Cook ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Dr. Nancy West, for her endless enthusiasm, continued encouragement, and excellent feedback throughout the drafting process and beyond. The final version of this thesis and my defense of it were made possible by Dr. West’s critique. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Joanna Hearne and Dr. Roger F. Cook, for their insights and thought-provoking questions and comments during my thesis defense. That experience renewed my appreciation for the ongoing conversations between scholars and how such conversations can lead to novel insights and new directions in research. In addition, I would like to thank Victoria Thorp, the Graduate Studies Secretary for the Department of English, for her invaluable assistance with navigating the administrative process of my thesis writing and defense, as well as Dr. -

26-30 October 2017 Ifi Horrorthon

IFI HORRORTHON IFI HORRORTHON 26-30 OCTOBER 2017 WELCOME TO THE DARK HALF (15.10) IFI HORRORTHON 2017! Romero’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel receives its first theatrical screening Horrorthon, Ireland’s biggest and best genre festival, returns in Ireland with Timothy Hutton as a novelist to the IFI this month for another packed programme. We’re whose violent alter ego comes to life and proud to present this year’s line-up, which features new films threatens his family. from directors whose previous work will be familiar to regular Dir: George A. Romero v 122 mins attendees, as well as films from Japan, Australia, Spain, Brazil, Italy, and Vietnam, proving the global reach and popularity of TOP KNOT DETECTIVE (17.25) horror. We hope you enjoy this year’s festival. This hilarious Australian mockumentary revolves around an obscure Japanese THURSDAY OCTOBER 26TH television show that survives only on VHS, OPENING FILM: and behind the scenes of which were TRAGEDY GIRLS (19.00) stories of rivalry and murder. From the director of Patchwork comes Dir: Aaron McCann, Dominic Pearse v 87 mins one of the freshest and funniest horror- comedies of the year, in which two HABIT (19.10) teenage girls turn to serial killing in order After Michael witnesses a brutal murder in to increase their social media following. the massage parlour for which he works Director Tyler MacIntyre will take part in a post-screening Q&A. as doorman, he is drawn deeper into the Dir: Tyler MacIntyre v 90 mins club’s secrets in this gritty British horror. -

Halloween Costume Guidelines for Safety Reasons, Masks Or Face Painting That Cover

Halloween Costume Guidelines Since Halloween falls on a school day this year, our ASB will be hosting a lunchtime celebration. Students wishing to participate will be allowed to wear costumes to school. However, if a student comes to school dressed inappropriately they will be asked to replace the costume entirely. If this is not possible, a parent will be asked to provide a change of clothes that are appropriate or pick up his/her child. We hope students enjoy the day, but it is still an instructional day and academics should not be compromised by those who desire to celebrate the day. San Clemente High School has set forth the following guidelines for Halloween: For safety reasons, masks or face painting that cover the student’s face is not permitted. No real, toy, or facsimile guns/ weapons (swords, play knives, etc.) are allowed. Costumes that are sexually suggestive and would otherwise violate the school’s dress code are not appropriate and cannot be worn. Costumes that are overly graphic, promote violence or otherwise might logically be assumed to be offensive to others are not acceptable. All costumes must be sensitive to all religious and ethnic groups; free from any language or symbols that target or inappropriately identify groups of students. Hats or wigs will be allowed if part of a costume and they do not pose a distraction to the learning environment; they must be removed at the request of any staff member Costumes should not include items with sound effects, lights or other components which would disrupt the classroom learning environment. -

Hatchet Iii (2013) Online

Hatchet iii (2013) online click here to download Watch online Hatchet III full with English subtitle. Watch online free Hatchet III, Caroline Williams, Kane Hodder, Danielle Harris, Zach Galligan, Derek. Watch Hatchet III, Hatchet III Full free movies Online HD. A search and recovery team heads into the haunted swamp to pick up the pieces. In Hatchet III, A search and recovery team heads into the haunted swamp to pick up the pieces and Marybeth learns the secret to ending the voodoo curse that. Watch Hatchet III Online here on Putlocker for free. A search and recovery team heads into the haunted swamp to pick up the pieces and. Watch Hatchet III Online For Free On moviesfree, Stream Hatchet III Online, Hatchet III Full Movies Free. Quality: HD. Release: Keywords. Watch Hatchet III Online on Putlocker. Stream Hatchet III in HD on Putlocker. IMDb: Caroline Williams, Kane Hodder, Danielle Harris, Zach Galligan. Hatchet 3 is a American slasher film written by Adam Green and directed by B. J. McDonnell. Subscribe to TRAILERS: www.doorway.ru Subscribe to COMING SOON: www.doorway.ru Like us on. Action · A search and recovery team heads into the haunted swamp to pick up the pieces and .. Amazon Affiliates. Amazon Video Watch Movies & TV Online · Prime Video Unlimited Streaming of Movies & TV · Amazon Germany Buy Movies. Buy Hatchet III: Read 43 Movies & TV Reviews - www.doorway.ru Hatchet III CC. Unsupported Browser Format, Amazon Video (streaming online video). Jednotka rýchleho nasadenia obkľúči chatrč v močiari, ktorý je domovom zabijaka menom Victor Crowley (Kane Hodder), s úmyslom nebezpečného vraha. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence.