Running Head: HORROR and HALLOWEEN 1 Horror, Halloween

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

Halloween Should Be Spooky, Not Scary! Governor Cuomo Asks for Your Help to Make Sure Everyone Has a Healthy and Safe Halloween

Halloween should be spooky, not scary! Governor Cuomo asks for your help to make sure everyone has a healthy and safe Halloween. Halloween celebrations and activities, including trick-or-treating, can be filled with fun, but must be done in a safe way to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The best way to celebrate Halloween this year is to have fun with the people who live in your household. Decorating your house or apartment, decorating and carving pumpkins, playing Halloween-themed games, watching spooky movies, and trick-or-treating through your house or in a backyard scavenger hunt are all fun and healthy ways to celebrate during this time. Creative ways to celebrate more safely: • Organize a virtual Halloween costume party with costumes and games. • Have a neighborhood car parade or vehicle caravan where families show off their costumes while staying socially distanced and remaining in their cars. • In cities or apartment buildings, communities can come together to trick-or-treat around the block or other outdoor spaces so kids and families aren’t tempted to trick-or-treat inside – building residents & businesses can contribute treats that are individually wrapped and placed on a table(s) outside of the front door of the building, or in the other outdoor space for grab and go trick-or-treating. • Make this year even more special and consider non-candy Halloween treats that your trick- or-treaters will love, such as spooky or glittery stickers, magnets, temporary tattoos, pencils/ erasers, bookmarks, glow sticks, or mini notepads. • Create a home or neighborhood scavenger hunt where parents or guardians give their kids candy when they find each “clue.” • Go all out to decorate your house this year – have a neighborhood contest for the best decorated house. -

Halloween Costume Guidelines for Safety Reasons, Masks Or Face Painting That Cover

Halloween Costume Guidelines Since Halloween falls on a school day this year, our ASB will be hosting a lunchtime celebration. Students wishing to participate will be allowed to wear costumes to school. However, if a student comes to school dressed inappropriately they will be asked to replace the costume entirely. If this is not possible, a parent will be asked to provide a change of clothes that are appropriate or pick up his/her child. We hope students enjoy the day, but it is still an instructional day and academics should not be compromised by those who desire to celebrate the day. San Clemente High School has set forth the following guidelines for Halloween: For safety reasons, masks or face painting that cover the student’s face is not permitted. No real, toy, or facsimile guns/ weapons (swords, play knives, etc.) are allowed. Costumes that are sexually suggestive and would otherwise violate the school’s dress code are not appropriate and cannot be worn. Costumes that are overly graphic, promote violence or otherwise might logically be assumed to be offensive to others are not acceptable. All costumes must be sensitive to all religious and ethnic groups; free from any language or symbols that target or inappropriately identify groups of students. Hats or wigs will be allowed if part of a costume and they do not pose a distraction to the learning environment; they must be removed at the request of any staff member Costumes should not include items with sound effects, lights or other components which would disrupt the classroom learning environment. -

Press Releases

Press Releases O’Melveny Guides ViacomCBS Through MIRAMAX Investment April 3, 2020 RELATED PROFESSIONALS FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Bruce Tobey CENTURY CITY—April 3, 2020—O’Melveny represented leading media and entertainment company Century City ViacomCBS (Nasdaq: VIACA; VIAC) in its acquisition of a 49percent stake in film and television studio D: +13102466764 MIRAMAX from beIN Media Group. The transaction, previously announced in December 2019, closed today. Amy Siegel ViacomCBS acquired 49 percent of MIRAMAX from beIN for a total committed investment of US$375 million. Century City Approximately US$150 million was paid at closing, while ViacomCBS has committed to invest US$225 million D: +13102466805 —comprised of US$45 million annually over the next five years—to be used for new film and television Silvia Vannini productions and working capital. Century City D: +13102466895 In addition, ViacomCBS’s historic film and television studio, Paramount Pictures, entered an exclusive, long term distribution agreement for MIRAMAX’s film library and an exclusive, longterm, firstlook agreement Eric Zabinski allowing Paramount Pictures to develop, produce, finance, and distribute new film and television projects Century City based on MIRAMAX’s IP. D: +13102468449 Rob Catmull ViacomCBS creates premium content and experiences for audiences worldwide, driven by a portfolio of Century City iconic consumer brands including CBS, Showtime Networks, Paramount Pictures, Nickelodeon, MTV, D: +13102468563 Comedy Central, BET, CBS All Access, Pluto TV, and Simon & Schuster. Eric H. Geffner beIN MEDIA GROUP is a leading independent global media group and one of the foremost sports and Century City entertainment networks in the world. -

The Horror Within the Genre

Alfred Hitchcock shocked the world with his film Psycho (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960), once he killed off Marion Crane (Janet Leigh) half way through the film. Her sister, Lila Crane (Vera Miles), would remain untouched even after Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) attacked her and her sisters lover. Unlike her sister, Lila did not partake in premarital sex, and unlike her sister, she survived the film. Almost 20 years later audiences saw a very similar fate play out in Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978). Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) managed to outlive her three friends on Halloween night. Once she slashed her way through Michael Myers (Nick Castle), Laurie would remain the lone survivor just as she was the lone virgin. Both Lila and Laurie have a common thread: they are both conventionally beautiful, smart virgins, that are capable of taking down their tormentors. Both of these women also survived a male murder and did so by fighting back. Not isolated to their specific films, these women transcend their characters to represent more than just Lila Crane or Laurie Strode—but the idea of a final girl, establishing a trope within the genre. More importantly, final girls like Crane and Strode identified key characteristics that contemporary audiences wanted out of women including appearance, morality, sexual prowess, and even femininity. While their films are dark and bloodstained, these women are good and pure, at least until the gruesome third act fight. The final girl is the constant within the slasher genre, since its beginning with films like Psycho and Peeping Tom (Michael Powell, 1960). -

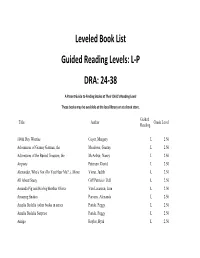

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L-P DRA: 24-38

Leveled Book List Guided Reading Levels: L‐P DRA: 24‐38 A Parent Guide to Finding Books at Their Child’s Reading Level These books may be available at the local library or at a book store. Guided Title Author Grade Level Reading 100th Day Worries Cuyer, Margery L 2.50 Adventures of Granny Gatman, the Meadows, Granny L 2.50 Adventures of the Buried Treasure, the McArthur, Nancy L 2.50 Airports Petersen, David L 2.50 Alexander, Who's Not (Do You Hear Me?..)..Move Viorst, Judith L 2.50 All About Stacy Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Amanda Pig and Her big Brother Oliver Van Leeuwen, Jean L 2.50 Amazing Snakes Parsons, Alexanda L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia (other books in series Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amelia Bedelia Surprise Parish, Peggy L 2.50 Amigo Baylor, Byrd L 2.50 Anansi the Spider McDermott, Gerald L 2.50 Animal Tracks Dorros, Arthur L 2.50 Annabel the Actress Starring in Gorilla My Dream Conford, Ellen L 2.50 Anna's Garden Songs Steele, Mary Q. L 2.50 Annie and the Old One Miles, Miska L 2.50 Annie Bananie Mover to Barry Avenue Komaiko, Leah L 2.50 Arthur Meets the President Brown, Marc L 2.50 Artic Son George, Jean Craighead L 2.50 Bad Luck Penny, the O'Connor Jane L 2.50 Bad, Bad Bunnies Delton, Judy L 2.50 Beans on the Roof Byare, Betsy L 2.50 Bear's Dream Slingsby, Janet L 2.50 Ben's Trumpet Isadora, Rachel L 2.50 B-E-S-T Friends Giff Patricia / Dell L 2.50 Best Loved doll, the Caudill, Rebecca L 2.50 Best Older Sister, the Choi, Sook Nyul L 2.50 Best Worst Day, the Graves, Bonnie L 2.50 Big Al Yoshi, Andrew L 2.50 Big Box of Memories Delton, -

Cinemeducation Movies Have Long Been Utilized to Highlight Varied

Cinemeducation Movies have long been utilized to highlight varied areas in the field of psychiatry, including the role of the psychiatrist, issues in medical ethics, and the stigma toward people with mental illness. Furthermore, courses designed to teach psychopathology to trainees have traditionally used examples from art and literature to emphasize major teaching points. The integration of creative methods to teach psychiatry residents is essential as course directors are met with the challenge of captivating trainees with increasing demands on time and resources. Teachers must continue to strive to create learning environments that give residents opportunities to apply, analyze, synthesize, and evaluate information (1). To reach this goal, the use of film for teaching may have advantages over traditional didactics. Films are efficient, as they present a controlled patient scenario that can be used repeatedly from year to year. Psychiatry residency curricula that have incorporated viewing contemporary films were found to be useful and enjoyable pertaining to the field of psychiatry in general (2) as well as specific issues within psychiatry, such as acculturation (3). The construction of a formal movie club has also been shown to be a novel way to teach psychiatry residents various aspects of psychiatry (4). Introducing REDRUMTM Building on Kalra et al. (4), we created REDRUMTM (Reviewing [Mental] Disorders with a Reverent Understanding of the Macabre), a Psychopathology curriculum for PGY-1 and -2 residents at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. REDRUMTM teaches topics in mental illnesses by use of the horror genre. We chose this genre in part because of its immense popularity; the tropes that are portrayed resonate with people at an unconscious level. -

Halloween Mayhem 6

NEWS RELEASE SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 Sixth Annual Halloween Mayhem Haunts KST with Spooky Fun for All Ages MEDIA CONTACT Zombies, a costume parade, puppets, live performances, games and more fill Kelly Strayhorn Theater on Friday, Saturday, October 25 from noon to 4 p.m. for the sixth annual Halloween Mayhem. Paula Simon Marketing Associate Halloween Mayhem promises a spooky day of activities designed to entertain the whole family. Festivi- 412.363.3000 x 310 ties include the return of KST’s friendly, giant puppets, Halloween-themed performances, and music [email protected] spun by guest DJ Vex, with emcee Lauren Bethea. Performances on the KST stage feature dance groups Alumni Theater Company (ATC), Trevor C. Dance Collective (TCDC), and IAS Christian Contempo- rary Dance Company, as well as numbers from Soundwaves, KST’s resident steel band ensemble. Toddlers and tweens can get creative with KST partner organizations, including free books from Read- ing is FUNdamental and face painting with paintOH! KST also partners with YWCA Greater Pitts- burgh Teen Services, Pittsburgh Glass Center, and Big Brothers Big Sisters of Greater Pittsburgh to provide Halloween activities, information, and giveaways. Patrons are encouraged to dress up in their favorite Halloween costume and join us onstage for the costume parade. In addition to complimentary refreshments, Halloween treats will be available for purchase at the KST concession stand in the lobby. “KST strives to provide quality entertainment for the family and community,” says janera solomon, executive director of KST. “Our diverse programming offers something for every age and generation.” Sixth Annual Halloween Mayhem Saturday, October 25 :: Noon – 4 PM Kelly Strayhorn Theater, 5941 Penn Ave, Pgh Pa. -

Apps for Staying in Touch on the Road Let Them Eat… Pumpkin

September–October 2018 Is Owning a Apps for Staying in Franchise Right Touch on the Road for You? Let Them Eat… Tips for Handling Pumpkin! Negative Online Reviews Halloween Movies for All Defining Your Next Chapter eptember and October often mean settling “next chapter” may be. We’ve also included tips to S into new routines for school, sports and other help you handle negative online reviews for your activities. Sometimes, the transition to something business and how to keep in touch with family and new can be challenging, but this doesn’t mean that friends when you are on the road. you shouldn’t try a new adventure—or two. Taking on new challenges is the focus of this issue of This time of year is also when signs of fall, such as Advantage. pumpkins and Halloween movies start to appear. Check out our unique pumpkin recipes and our list From how to make the transition to retirement of some of the greatest Halloween films so that you easier to determining if owning a franchise is the can truly enjoy the season. right challenge for you, we’re covering a lot of ground to help you feel at ease—whatever your Your Trusted Accounting Advisors 2 | SEPTEMBER–OCTOBER 2018 September–October 2018 Features 4 4 • 5 Tips to Keep Your Retirement on Track Proactively preparing for retirement is essential. Here’s some advice to help you do it. 6 • Apps for Staying in Touch on the Road If you’re taking off on vacation or an extended trip for work, pack this list of apps to help you stay in touch while on the road. -

Movie Review: 'Halloween'

Movie Review: ‘Halloween’ NEW YORK (CNS) — One of modern Hollywood’s most enduring horror franchises turns 40 this year. To mark the occasion, director and co-writer David Gordon Green presents us with “Halloween” (Universal), a direct sequel to the eponymous 1978 original. Neither the anniversary nor the picture intended to salute it is any cause for celebration, however. As with helmer and script collaborator (with Debra Hill) John Carpenter’s kickoff, things begin rather promisingly. Moviegoers of a certain age may recall the suburban peace and quiet, accented with autumnal beauty, with which Carpenter skillfully induced his audience to share in his complacent characters’ false sense of security before unleashing masked madman Michael Myers — (then, as now, Nick Castle) — on them. Green, by contrast, gives us some interesting exposition concerning insecurity. The opening scenes explore the enduring psychological effects on Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis), the intrepid sole survivor of the first of Myers’ many blood- soaked rampages, of that long-ago night of terror. As a duo of investigative journalists, Aaron Korey (Jefferson Hall) and Dana Haines (Rhian Rees), discover, after tracking the semi-recluse down, Laurie soon went into, and unapologetically remains in, survivalist mode. What follows might have been a thoughtful study of the impact of evil across time and generations. Both Laurie’s grown daughter, Karen (Judy Greer), and teen granddaughter, Allyson (Andi Matichak) have had their relationships with her strained by her fears, self-imposed isolation and apparent paranoia, while Dr. Sartain (Haluk Bilginer), the psychiatrist who has had charge of the captive Myers for decades, has become obsessed with him. -

HALLOWEEN 7 TREATMENT by Kevin Williamson LAURIE STRODE, Thought Dead, Is Discovered to Be Very Much Alive and Living a Quiet

HALLOWEEN 7 TREATMENT By Kevin Williamson LAURIE STRODE, thought dead, is discovered to be very much alive and living a quiet and content life as mother and teacher at a small New England all girl's prep school. But with the Eve of All Saints quickly approaching, Laurie Strode’s world will once again be ripped apart by the arrival of an old member of the family. PITCH: Chicago Suburbs. Night. We open on a woman coming home to find her front door ajar. Scared, she goes next door to enlist the help of a neighbor. A temage boy. They call the cops. The woman, afraid someone has broken into her home, is scared to go inside. While waiting for the cops, we learn the woman is Rachel Loomis - daughter of Dr. Loomis. The teenager - Timmy is bored, he's missing SEINFELD. The cops are taking too long. Timmy decides to check the house out himself. Armed with a baseball bat, Timy goes inside the house while a fearful Rachel stands outside. Inside the house, Timmy discovers nothing amiss. The house is empty. He returns outside and tells Rachel. He says goodnight, leaving her alone. She goes inside and locks and bolts the front door. She checks the house out. It does not appear to be burglarized. RING! Rachel jumps when the phone rings. She answers. It is the police. They're still on their way. Rachel continues checking the place over. Everything seems fine. Except in her office. Certain files have been opened. We glance them. The name KERI TATE is glimpsed. -

GWCA Annual Halloween Weeks Weeks of Halloween Fun & Mayhem

GWCA Annual Halloween Weeks Beginning October 15 through October 31 Weeks of halloween fun & mayhem 1. House Decorating Contest 2. “Ghosting” your neighbors! 3. Annual Halloween Costume Parade 4. Halloween Party 10/28 @warner park 5. Trick or Treating - 10/31 from 5:30 - 8:00pm GWCA Annual Halloween Event Sunday October 28 from 12pm - 1:30pm at Warner Park Fun filled activities for all and lots of treats Special Costume Parade: Begins at We ask that our neighbors bring some Noon at the corner of Greenview & treats to help our event. Block Hutchinson so be sure to line up early to assignments are as follows: show off your best costumes - Cuyler, Belle Plaine, & Warner = Juice Boxes Food available so come hungry! - Hutchinson, & Pensacola = Mini Water Bottles - Greenview, Berteau, & Cullom = Candy Costume Contest with prizes for all ages - including adults All donations of Candy are welcome! We need volunteers please email [email protected] if you can help GWCA HALLOWEEN 1ST ANNUAL HOUSE DECORATING CONTEST Beginning October 15 through October 31!! Decorate your home to be the scariest in Chicago. Houses may be decorated anytime prior to Oct. 26. Your house must be within Graceland West boundaries. Judging will take place the evening of Oct. 27 . Winning entrants will be announced at the Halloween Party on Oct. 28 and featured on GWCA.org. The criteria that will be judged is as follows: Originality: Unique design and creative use of lights and decorations Arrangement: Display and placement of decorations Theme: Storyline or scene Overall: Overall presentation $5.00 Entry Fee - Prizes will be awarded Email [email protected] to register your home for judging .