How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Read an Excerpt

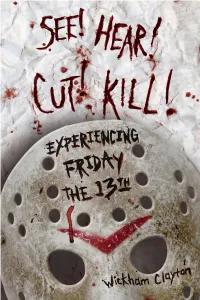

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Production Notes

PUBLICITY CONTACTS LA NATIONAL Karen Paul Anya Christiansen Chris Garcia – 42 West (310) 575-7033 (310) 575-7028 (424) 901-8743 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] NY NATIONAL Sara Groves – 42 West Tom Piechura – 42 West Jordan Lawrence – 42 West (212) 774-3685 (212) 277-7552 (646) 254-6020 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] REGIONAL Gillian Fischer Linda Colangelo (310) 575-7032 (310) 575-7037 [email protected] [email protected] DIGITAL Matt Gilhooley Grey Munford (310) 575-7024 (310) 575-7425 [email protected] [email protected] Release Date: May 31, 2013 (Limited) Run Time: 92 Minutes For all approved publicity materials, visit www.cbsfilmspublicity.com THE KINGS OF SUMMER Preliminary Production Notes Synopsis Premiering to rave reviews at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival, THE KINGS OF SUMMER is a unique coming-of-age comedy about three teenage friends – Joe (Nick Robinson), Patrick (Gabriel Basso) and the eccentric and unpredictable Biaggio (Moises Arias) - who, in the ultimate act of independence, decide to spend their summer building a house in the woods and living off the land. Free from their parents’ rules, their idyllic summer quickly becomes a test of friendship as each boy learns to appreciate the fact that family - whether it is the one you’re born into or the one you create – is something you can't run away from. ABOUT THE PRODUCTION The Kings of Summer began in the imagination of writer Chris Galletta, who penned his script during his off hours while he was working in the music department of “The Late Show with David Letterman.” After some false starts in screenwriting, Galletta shunned his impulse to write a high-concept tentpole feature and craft something more character-driven and personal. -

The Impact of Social Media on a Movie's Financial Performance

Undergraduate Economic Review Volume 9 Issue 1 Article 10 2012 Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance Joshua J. Kaplan State University of New York at Geneseo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer Part of the Economics Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kaplan, Joshua J. (2012) "Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance," Undergraduate Economic Review: Vol. 9 : Iss. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/uer/vol9/iss1/10 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Turning Followers into Dollars: The Impact of Social Media on a Movie’s Financial Performance Abstract This paper examines the impact of social media, specifically witterT , on the domestic gross box office revenue of 207 films released in the United States between 2009 and 2011. -

Scream If You Like His Movies Kevin Williamson’S Strange Ride

spring 2012 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy erber g scream if you . s like his movies Kevin Williamson’s strange ride Copyright 2011 by Max by 2011 Copyright from Dawson’s Creek to hollywood vieWfinDer spring 2012 EastThe Magazine of easT Carolina UniversiTy Construction worker Willie Joyner Jr. is part of the renovation of Tyler residence Hall, one of the older dorms on College Hill. Opened as a men’s residence in 1969, it was switched to all women in FEATUrEs 1972 and remained so for 20 30 years. it was named for sCreaM if YOU liKe his MOVIES Arthur Lynwood Tyler, a 2 0 His TV series became former university trustee. By David Menconi Dawson’s Creek Photograph by Forrest Croce iconic, then Kevin Williamson ’87 became king of the scary movie genre and now his scripts about teenage vampires fill primetime TV. He’s had hits and some misses, so now he’s hoping to find an elusive balance in his creative and personal lives. “I’m not good at highs and lows,” he says. hearT Throb 3 0 Professor Sam Sears, a leading 30 authorityBy Spaine onStephens the psychology of living with what are called implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs), helps patients adjust to living with the constant worry that the device will deliver a 700-volt punch. “It’s a modern-day paradox of safety and fear,” he says. “I see more courage on a daily basis than anyone.” genTle gianT 3 6 For 24 years, Dean of Students James TuckerBy Steve laid Tuttle down ’09 the law on campus, from the time of the Big Yellow House Incident through the protests over the 36 Vietnam War. -

Horror Genre in National Cinemas of East Slavic Countries

Studia Filmoznawcze 35 Wroc³aw 2014 Volha Isakava University of Ottawa, Canada HORROR GENRE IN NATIONAL CINEMAS OF EAST SLAVIC COUNTRIES In this essay I would like to outline several tendencies one can observe in con- temporary horror fi lms from three former Soviet republics: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. These observations are meant to chart the recent (2000-onwards) de- velopment of horror as a genre of mainstream cinema, and what cultural, social and political forces shape its development. Horror fi lm is of particular interest to me because it is a popular genre known for a long and interesting history in American cinema. In addition, horror is one of transnational genres that infuse Hollywood formula with particularities of national cinematic traditions (most no- table example is East Asian horror cinema, namely “J-horror,” Japanese horror). To understand the peculiarity of the newly emerged horror genre in the cinemas of East Slavic countries, I propose two venues of exploration, or two perspectives. The fi rst one could be called the global perspective: horror fi lm, as it exists today in post-Soviet space, is profoundly infl uenced by Hollywood. Domestic produc- tions compete with American fi lms at the box offi ce and strive to emulate genre structures of Hollywood to attract viewers, whose tastes are largely shaped by American fi lms. This is especially true for horror, which has almost no reference point in national cinematic traditions in question. The second vantage point is local: the local specifi city of these horror narratives, how the fi lms refl ect their own cultural condition, shaped by today’s globalized cinema market, Hollywood hegemony and local sensibilities of distinct cinematic and pop-culture traditions. -

The Final Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016 Lauren Cupp Scripps College Recommended Citation Cupp, Lauren, "The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 958. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/958 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FINAL GIRL GROWN UP: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN HORROR FILMS FROM 1978-2016 by LAUREN J. CUPP SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TRAN PROFESSOR MACKO DECEMBER 9, 2016 Cupp 2 I was a highly sensitive kid growing up. I was terrified of any horror movie I saw in the video store, I refused to dress up as anything but a Disney princess for Halloween, and to this day I hate haunted houses. I never took an interest in horror until I took a class abroad in London about horror films, and what peaked my interest is that horror is much more than a few cheap jump scares in a ghost movie. Horror films serve as an exploration into our deepest physical and psychological fears and boundaries, not only on a personal level, but also within our culture. Of course cultures shift focus depending on the decade, and horror films in the United States in particular reflect this change, whether the monsters were ghosts, vampires, zombies, or aliens. -

David Arquette Will Return to Pursue Ghostface As Dewey Riley in the Relaunch of Scream for Spyglass Media Group

DAVID ARQUETTE WILL RETURN TO PURSUE GHOSTFACE AS DEWEY RILEY IN THE RELAUNCH OF SCREAM FOR SPYGLASS MEDIA GROUP James Vanderbilt and Guy Busick to Co-write the Screenplay With Project X Entertainment Producing, Creator Kevin Williamson Serving as Executive Producer and the Filmmaking Collective Radio Silence at the Helm LOS ANGELES (May 18, 2020)— David Arquette will reprise his role as Dewey Riley in pursuit of Ghostface in the relaunch of “Scream,” it was announced today by Peter Oillataguerre, President of Production for Spyglass Media Group, LLC (“Spyglass”). Plot details are under wraps but the film will be an original story co-written by James Vanderbilt (“Murder Mystery,” “Zodiac,” “The Amazing Spider-Man”) and Guy Busick (“Ready or Not,” “Castle Rock,”) with Project X Entertainment’s Vanderbilt, Paul Neinstein and William Sherak producing for Spyglass. Creator Kevin Williamson will serve as executive producer. Matt Bettinelli- Olpin and Tyler Gillett of the filmmaking group Radio Silence (“Ready or Not,” “V/H/S”) will direct and the third member of the Radio Silence trio, Chad Villella, will executive produce alongside Williamson. Principal photography will begin later this year in Wilmington, North Carolina when safety protocols are in place. Arquette said, “I am thrilled to be playing Dewey again and to reunite with my ‘Scream’ family, old and new. ‘Scream’ has been such a big part of my life, and for both the fans and myself, I look forward to honoring Wes Craven’s legacy.” Though Arquette is the first member of the film’s ensemble to be officially announced, conversations are underway with other legacy cast. -

Un Secolo Di Cinema Firmato Bava – 2003

UN SECOLO DI CINEMA FIRMATO BAVA di Renato Venturelli La leggenda dei Bava, al cinema, dura ormai da quasi un secolo. Di padre in figlio, di figlio in nipote, è già arrivata alla quarta generazione: prima Eugenio (Francesco) Bava, eccentrica figura di inventore e mago degli effetti speciali fin dagli anni della Belle Epoque poi Mario, geniale direttore della fotografia e regista, oggetto di culto in tutto il mondo; quindi Lamberto, che cominciò lavorando al fianco del padre negli anni Sessanta diventando poi autore cinematografico e televisivo. E adesso Roy, che ha iniziato da qualche anno la sua carriera. Tutto era cominciato all’inizio del Novecento, quando nonno Eugenio (1886-1966) ricevette il primo incarico da parte del cinema: la costruzione di un caminetto per un film Pathé. All’epoca, aveva appena compiuto vent’anni, essendo nato a Sanremo nel 1886, e secondo il figlio Mario era il prototipo dell’artista bohémien. «Cravatta e fiocco rivoluzionario, basco alla Raffaello) era un artista - disse in un famoso intervento del 1976- era pittore, scultore,fotografo, chimico, elettricista, medium, inventore; perse anni a studiare il moto perpetuo. Verso il 1908 per una succosa storia, purtroppo troppo lunga da raccontare, conobbe il cinema. Si “incimiciò”, dette un calcio al passato, e si gettò a capofitto nella Nuova Arte, diventando operatore: all’epoca non si diceva direttore della fotografia.. «E non si chiamava nemmeno Eugenio — aggiunge Lamberto— ma Francesco: è il nome scritto anche sulla sua tomba». Negli anni Dieci, il capostipite dei Bava lavorò nella sua città, fondando anche la “San Remo Film”, poi passò all’Ambrosio di Torino, quindi si stabilì a Roma, responsabile del Reparto Animazione e Trucchi dell’istituto Luce, escogitando trucchi ed effetti speciali fin quasi alla morte, avvenuta nel 1966,quando aveva ottant’anni. -

Superstars Align Under a Full Moon for Spike's 'SCREAM 2010'

Superstars Align Under a Full Moon for Spike's 'SCREAM 2010' OCEANIC FLIGHT 815 TO LAND AS CAST AND CREATORS OF 'LOST' RECEIVE A FINAL FAREWELL Kristen Stewart, Megan Fox, Alexander Skarsgard, Mickey Rourke, Chris Hemsworth And Marilyn Manson Added To Roster Of Celebrities To Appear 'Lost' Castmembers Harold Perrineau, Henry Ian Cusick And Jorge Garcia To Attend Along With Show Creators Carlton Cuse And Damon Lindelof 'SCREAM 2010' To Also Feature Musical Performance By Grammy And Academy Award-Nominated Recording Artist M.I.A. And Premieres Tuesday, October 19 At 9PM, ET/PT NEW YORK, Oct 07, 2010 /PRNewswire via COMTEX/ -- Months after millions of viewers were riveted by "Lost's" finale, fans will be given the opportunity to bid a final farewell to the landmark series, as "SCREAM 2010" brings together the show's cast and creators, including Jorge Garcia, Harold Perrineau, Henry Ian Cusick, Carlton Cuse and Damon Lindelof, for a tribute to the survivors of Oceanic Flight 815. More cast will be announced shortly. The two-hour event premieres on Spike TV on Tuesday, October 19 (9:00 - 11:00 PM, ET/PT). (Logo: http://photos.prnewswire.com/prnh/20060322/NYW096LOGO) (Logo: http://www.newscom.com/cgi-bin/prnh/20060322/NYW096LOGO) The show will feature a musical performance by Grammy and Academy Award-nominee M.I.A., as well as appearances by Kristen Stewart, Megan Fox, Mickey Rourke, Marilyn Manson and Chris Hemsworth. These luminaries join a host of previously announced "SCREAM 2010" talent, including the reunion of Michael J. Fox, Lea Thompson -

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes ...........................................Christopher J. Garcia ....................................................................................................3 Letters of Comment .....................................Jean Martin and Chris Garcia ....................................................................................4-6 Editorial .......................................................Jean Martin ................................................................................................................... 7 Ghosts and Surreal Art in Portland ...............Jean Marin ................................Photos Jean Martin ................................................8-11 Nemo Gould Sculptures ...............................Espana Sheriff ...........................Photos from www.nemomatic.com ......................12-13 Reading at Intersection for the Arts ..............Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................14-15 Klingon Celebration .....................................Jean Marin ................................Photos by Jean Martin .........................................16-21 BASFA Minutes ..........................................................................................................................................................................22-24