Elder-At-The-Fire: Missional Generativity Jo A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pieter Bruegel's the Beekeepers| Protestants, Catholics, Birds, and Bees| Beehive Rustling on the Low Plains of Flanders

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2004 Pieter Bruegel's The Beekeepers| Protestants, Catholics, birds, and bees| Beehive rustling on the low plains of Flanders Edgar W. Smith The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Edgar W., "Pieter Bruegel's The Beekeepers| Protestants, Catholics, birds, and bees| Beehive rustling on the low plains of Flanders" (2004). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3222. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3222 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. a; Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Flease check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature:_____ Date:__________________ Y Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 PIETER BRUEGEL’S THE BEEKEEPERS PROTESTANTS, CATHOLICS, BIRDS, AND BEES: Beehive Rustling on the Low Plains of Flanders by Edgar Smith B.A. -

Current Vita Flaxen D.L. Conway A. Employment, Professional

Current Vita July 2015 Flaxen D.L. Conway Director, Marine Resource Management Graduate Program Professor, School of Public Policy Extension Community Outreach Specialist, Oregon Sea Grant 104 CEOAS Admin, Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331 Phone: 541-737-1339 Fax: 541-737-2064 E-mail: [email protected] A. Employment, Professional Development, and Education 1. Employment May 2011 to present Oregon State University, College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences, Corvallis, OR Director of the Marine Resource Management graduate program. July 08 to present Oregon State University, Cooperative Extension Service Corvallis, OR Extension Community Outreach Specialist / Professor. Jun 02 to Jun 08 Oregon State University, Cooperative Extension Service Corvallis, OR Extension Community Outreach Specialist / Associate Professor. Jul 91 to Jun 02 Oregon State University, Cooperative Extension Service Corvallis, OR Extension Community Outreach Specialist / Assistant Professor. May 89 - Jul 91 Oregon State University Cooperative Extension Service Corvallis, OR Extension Technology Outreach Agent / Assistant Professor. Jan 87 - Apr 89 Organically Grown Cooperative Eugene, OR Operations Director and Horticultural Consultant. Jun 84 - Jun 86 Oregon State University, Department of Horticulture Corvallis, OR Graduate Research/Teaching Assistant. 2. Professional Development March 2015 Society for Applied Anthropology, 4-day conference for members of my field. This year in Pittsburgh, PA. Sept 2014 2nd World Small-Scale Fisheries Congress, Merida, Mexico. By invitation only. March 2014 Society for Applied Anthropology, 4-day conference for members of my field. This year in Albuquerque, NM. Flaxen D.L. Conway June 2013 “Fishing Futures: Articulating Alternatives in North American Small-Scale Fisheries” Workshop. Too Big to Ignore (Global Partnership for Small-Scale Fisheries Research), Vancouver, BC, Canada. -

Heart of Anglicanism Week #1

THE HEART OF ANGLICANISM #1 What Exactly Is an Anglican? Rev. Carl B. Smith II, Ph.D. WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE ANGLICAN? ANGLICANISM IS… HISTORICAL IN ORIGIN • First Century Origin: Christ and Apostles (Apostolic) • Claims to Apostolicity (1st Century): RCC & Orthodox • Protestants → through RCC (end up being anti-RCC) • Church of England – Anglican Uniqueness • Tradition – Joseph of Arimathea; Roman Soldiers; Celtic Church; Augustine of Canterbury; Synod of Whitby (664), Separated from Rome by Henry VIII (1534; Reformation) • A Fourth Branch of Christianity? BRANCHES OF CHRISTIAN CHURCH GENERALLY UNIFIED UNTIL SCHISM OF 1054 Eastern Church: Orthodox Western Church: Catholic Patriarch of Constantinople Reformation Divisions (1517) • Greek Orthodox 1. Roman Catholic Church • Russian Orthodox 2. Protestant Churches • Coptic Church 3. Church of England/ • American Orthodox Anglican Communion (Vatican II Document) NAME CHANGES THROUGH TIME • Roman Catholic until Reformation (1534) • Church of England until Revolutionary War (1785) • In America: The (Protestant) Episcopal Church • Break 2009: Anglican Church in North America • Founded as province of global Anglican Communion • Recognized by Primates of Global Fellowship of Confessing Anglicans (African, Asian, So. American) TWO PRIMARY SOURCES OF ACNA A NEW SENSE OF VIA MEDIA ACNA ANGLICANISM IS… DENOMINATIONAL IN DISTINCTIVES Certain features set Anglicanism apart from other branches of Christianity and denominations (e.g., currency): • Book of Common Prayer • 39 Articles of Religion (Elizabethan Settlement; Via Media) • GAFCON Jerusalem Declaration of 2008 (vs. TEC) • Provincial archbishops – w/ A. of Canterbury (first…) • Episcopal oversight – support and accountability ANGLICANISM IS… EPISCOPAL IN GOVERNANCE • Spiritual Authority – Regional & Pastoral • Provides Support & Accountability • Apostolic Succession? Continuity through history • NT 2-fold order: bishop/elder/pastor & deacons • Ignatius of Antioch (d. -

Appendix 7 Investment in Independent Production

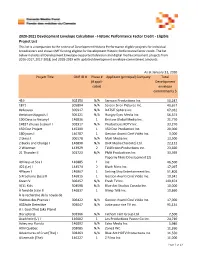

APPENDIX 7 INVESTMENT IN INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION ABRIDGED Appendix 7 - Expenditures on Programming and Development on Independent Productions in Quebec (Condition of licence 23) CBC English Television 2019-2020 SUMMARY Programming Expenditure* All Independents* Quebec independents Percentage 131,425,935 5,895,791 4.5% Development Expenditures All Independents Quebec independents Percentage #### #### 8.5% Note: * Expenses as shown in Corporation's Annual Reports to the Commission, line 5 (Programs acquired from independent producers), Direct Operation Expenses section. Appendix 7-Summary Page 1 ABRIDGED APPENDIX 7 - CANADIAN INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION EXPENDITURES - DETAILED REPORT CBC English Television 2019-2020 Program Title Expenditures* Producer / Address Producer's Province A Cure For What Hails You - 2013 #### PYRAMID PRODUCTIONS 1 INC 2875 107th Avenue S.E. Calgary Alberta Alberta Digging in the Dirt #### Back Road Productions #102 – 9955 114th Street Edmonton Alberta Alberta Fortunate Son #### 1968 Productions Inc. 2505 17TH AVE SW STE 223 CALGARY Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND S 1-7 #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND S13 #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND X #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta HEARTLAND XII #### Rescued Horse Season Inc. 223, 2505 - 17th Avenue SW Calgary Alberta Alberta Lonely #### BRANDY Y PRODUCTIONS INC 10221 Princess Elizabeth Avenue Edmonton, Alberta Alberta Narii - Love and Fatherhood #### Hidden Story Productions Ltd. 347 Sierra Nevada Place SW Calgary Alberta T3H3M9 Alberta The Nature Of Things - A Bee's Diary #### Bee Diary Productions Inc. #27, 2816 - 34 Ave Edmonton Alberta Alberta A Shine of Rainbows #### Smudge Ventures Inc. -

Elder Massimo De Feo: ‘Welcome to the Lord’S Temple in Rome’

Elder Massimo De Feo: ‘Welcome to the Lord’s Temple in Rome’ Elder Massimo De Feo and his wife, Loredana Galeandro, pose for photos at the Church Office Building in Salt Lake City Monday, April 4, 2016. April 3, 2016, will forever be a historic day for members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter- day Saints in Italy. For the first time, one of their own was called to be a senior Church leader. While Elder Massimo De Feo’s recent assignment as a General Authority Seventy signaled a key moment in Church history, his own introduction to the Church was far more commonplace. When missionaries knocked on the De Feo family’s door in Taranto in 1970, 9-year-old Massimo and his older brother Alberto were taught the gospel and were later baptized. While Massimo and Alberto’s parents never joined the Church, they were supportive of their sons as they became active in their new faith. “Our parents never accepted the gospel, but they felt it was good and they felt good about their two children growing up in the gospel with good principles,” Elder De Feo said. Alberto and Massimo’s beliefs were challenged outside the home. They were the only members in their school in a community with deep Catholic roots and centuries-old traditions. The brothers made it a point to avoid contention and looked for opportunities to explain The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with others. Although the Church in Taranto was small, Massimo said leaders, teachers and youth advisers always made him feel he belonged. -

Elder-Led Congregationalism at Meadow Creek Church Sunday Night Gatherings May 20 – July 22Nd 2018

Elder-Led Congregationalism at Meadow Creek Church Sunday Night Gatherings May 20 – July 22nd 2018 The purpose of our 10 Weeks of Gathering: May 20th (Craig Howse) This is the coming together of the body to think and wrestle through 10 questions on elder leadership to answer one question: “Should Meadow Creek Church adopt elder leadership?” As we do this, we are acknowledging the biblical roots of the Meadow Creek and this church’s deep love for the Bible. I love that about Meadow Creek. We have discussed and we believe that the existing deacon based governance structure grew out of the early members’ understanding of the Bible and their experiences. We want to build on that and pursue further our understanding of biblical church leadership and its forms. A word about resources. As we tackle each of these questions, there are a number of men studying together and we are using a number of resources. o Would the men who have been part of this study so far please stand? This is helpful as we are laboring to handle God’s word accurately and the questions and probing of others helps us do that. o We are also helped by a number of resources. If you are interested in those resources, see me afterwards, and I can share the titles with you. o Tonight, we want to give you two of the resources: . Understanding Church Leadership, and . Understanding the Congregation’s Authority. We have 30 copies of each. You should take a set per family, if you will read them. -

Elder Update August 2020 Don Provided the Elder Reflection from Psalm 133 on Unity of the Elder and of the Body of Christ. O

Elder Update August 2020 This new communication method is an effort by your SBC Elders to better connect with and update our church family on some of the activities with which the Elder board has been involved. For more information or to share concerns please contact one of your SBC Elders. There are normally two elder board meetings each month. The first meeting will include staff, and focus on staff development and prayer. The second monthly meeting will include only the elders and will focus on our agenda considerations. ● Don provided the Elder Reflection from Psalm 133 on unity of the elder and of the body of Christ. Our unity is a blessing from God, born of humility under His Lordship, modeled among our people, and strengthening us in our service in the Kingdom together. ● Funds on hand are doing well one month into the new church year. We continue to be grateful for the faithfulness of the SBC community. ● Pastor Steve described the next series of Sunday messages on the Life of Jesus. The series will concentrate on five significant characteristics of the life of Jesus: ‣ Where I see the power of Jesus ‣ Where I see the wisdom and brilliance of Jesus ‣ Where I see the grace, mercy, and forgiveness of Jesus ‣ Where I see the new life of Jesus ‣ Where I find hope through Jesus Our vision and purpose is to help our people become rooted again in the gospels. ● We are developing new Ministry Teams, to (a) broaden our leadership to be more mission-driven, (b) deepen our leadership to be mixed-gender and multi-generational, and (c) help more people actively participate and be equipped for SBC’s mission. -

A Strategy to Train Local Church Elders for Effective Assimilation And

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Project Documents Graduate Research 2014 A Strategy to Train Local Church Elders for Effective Assimilation and Nurture of New Converts Enock Chifamba Andrews University This research is a product of the graduate program in Doctor of Ministry DMin at Andrews University. Find out more about the program. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Missions and World Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Chifamba, Enock, "A Strategy to Train Local Church Elders for Effective Assimilation and Nurture of New Converts" (2014). Project Documents. 262. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/262 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Project Documents by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. ABSTRACT A STRATEGY TO TRAIN LOCAL CHURCH ELDERS FOR EFFECTIVE ASSIMILATION AND NURTURE OF NEW CONVERTS by Enock Chifamba Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A STRATEGY TO TRAIN LOCAL CHURCH ELDERS FOR EFFECTIVE ASSIMILATION AND NURTURE OF NEW CONVERTS Name of researcher: Enock Chifamba Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss Date completed: October 2014 Problem In most multi-church districts the pastoral burden rests with the local church elders. -

Elder Covenants of Conduct

A Guide to Elder Covenants of Conduct Resources for the relationships between elders and congregations Compiled in September 2016 by the Siburt Institute for Church Ministry siburtinstitute.org Additional Resources from the Siburt Institute for Church Ministry Church Health Assessment This robust and statistically reliable instrument helps church leaders by gathering and reporting congregational members’ perceptions on nine different areas such as ministry effectiveness, spiritual formation and discipleship, congregational culture and values, and family life stages. Learn more: siburtinstitute.org/cha Leadership Seminars and Events Numerous seminars and training events take place throughout the year in various U.S. cities. Examples include ACU Summit, Equipping for Ministry, and Summer Seminar. Learn more: siburtinstitute.org/events acusummit.org Minister Transition Guidance and Resources The Looking Team is an active group that helps churches find candidates for open ministry positions. MinistryLink is a web-based service connecting ministers and churches to help fill ministry positions. Resource packets are also available to assist churches and ministers with navigating ministerial transitions in constructive and healthy ways. Learn more: siburtinstitute.org/transition Mosaic Blog This blog curates reflections on Christian leadership, spiritual vitality, and cultural engagement. Mosaic seeks to engage Christian leaders, congregational ministers, and others who care deeply about the church and her mission, matters of faith, and what God is doing in the world. Learn more: mosaicsite.org Connect Contact us: [email protected] 325-674-3722 Sign up for our monthly e-newsletter: siburtinstitute.org/subscribe Follow us @SiburtInstitute: Facebook Twitter YouTube Equipping and serving church leaders and other Christ-followers for God’s mission in the world Table of Contents The Ministry of an Elder ................................................................................................. -

Long Wave Dynamics in the Coastal Zone

THESIS ON CIVIL ENGINEERING F16 Long Wave Dynamics in the Coastal Zone IRA DIDENKULOVA TUT PRESS TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Faculty of Civil Engineering Department of Environmental Engineering Institute of Cybernetics, Tallinn University of Technology The dissertation was accepted for the defence of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy on June 3, 2008 Supervisors: Prof. Tarmo Soomere Institute of Cybernetics Tallinn University of Technology, Estonia Prof. Efim Pelinovsky Department of Mathematical Sciences Loughborough University, UK Department of Nonlinear Geophysical Processes Institute of Applied Physics Russian Academy of Sciences, Russia Opponents: Prof. Geir Pedersen Department of Mathematics University of Oslo, Norway Prof. Kevin Parnell School of Earth and Environmental Sciences James Cook University, Australia Defence of the thesis: 21 July 2008 Declaration: Hereby I declare that this doctoral thesis, my original investigation and achievement, submitted for the doctoral degree at Tallinn University of Technology has not been submitted for any academic degree. /Ira Didenkulova/ Copyright: Ira Didenkulova, 2008 ISSN 1406-4766 ISBN 978-9985-59-816-0 EHITUS F16 Pikkade lainete dünaamika rannavööndis IRA DIDENKULOVA TUT PRESS The ocean is a wilderness reaching round the globe, wilder than a Bengal jungle, and fuller of monsters, washing the very wharves of our cities and the gardens of our sea-side residences. Henry David Thoreau “The Writings of Henry David Thoreau”, vol. 4, 1906 Contents List of Tables .................................................................................................8 -

Spring 2018 Issue #8

SPRING 2018 ISSUE #8 In this issue… th Annual Meeting of the American Meteologist Society Tsunami Warning Communications Test – March 28 by Ricky Lam Annual Meeting of the American Meteorological Society Sneaker Wave & Beach Safety The 98th Annual Meeting of the Several Local Records Set This Winter American Meteorological Society Rain, Snow, & Hail Observers Still Needed! was held in Austin, TX from January NWS Eureka Info Available by Telephone 7th to 11th, 2018. In this annual Science of River Flooding meeting, over 4,000 meteorologists, Magnitude 7.9 Earthquake Near Kodiak, Alaska scientists, educators, students, and Tsunami Safety other professionals from across the Regular Features… weather, water, and climate community Climate Page: Winter Wrap-up & Spring Outlook gathered to share, learn, and collaborate. The figure below Night Sky Corner shows some interesting statistics about this meeting. Upcoming Events Tsunami Warning Communications Test – March 28th by Ryan Aylward Part of ensuring the area’s tsunami safety includes testing the emergency alert system. Testing the system allows us to be confident that our communication system is working and Image courtesy of the American Meteorological Society able to reach you with emergency information when it’s T needed most. On Wednesday, March 28th, there will be a test he following image is a snapshot of meteorologists of the emergency alert system between 11am and Noon. reviewing posters created by their peers. These posters This test will interrupt radio and television programming, showcased cutting-edge research projects in different areas activate NOAA weather radios, and turn on sirens in some of meteorology, including: tropical, artificial intelligence, areas. -

CMF 2020-2021 Development Historic Performance Project List.Xlsx

2020‐2021 Development Envelope Calculation ‐ Historic Performance Factor Credit ‐ Eligible Project List This list is a companion to the review of Development Historic Performance eligible projects for individual broadcasters and shows CMF funding eligible for Development Historic Performance factor credit. The list below includes all Development Envelope‐supported television and digital media component projects from 2016‐2017, 2017‐2018, and 2018‐2019 with updated development envelope commitment amounts. As at January 31, 2020 Project Title CMF ID # Phase # Applicant (principal) Company Total (if appli‐ Development cable) envelope commitments $ 419 302150 N/A Sarrazin Productions Inc. 50,247 1871 305894 N/A Screen Siren Pictures Inc. 40,657 #elleaussi 305917 N/A DATSIT Sphère inc. 67,032 #relationshipgoals I 305121 N/A Hungry Eyes Media Inc. 56,374 100 Days to Victory I 146836 1 Bristow Global Media Inc. 21,770 14837 choses à savoir I 302917 N/A Productions KOTV Inc. 33,270 150 Doc Project 145309 1 150 Doc Production Inc. 20,000 180 jours I 146787 1 Gestion Avanti Ciné Vidéo Inc. 3,000 2 bleus I 306578 N/A Maki Media inc 13,500 2 Bucks and Change I 146890 N/A DHX Media (Toronto) Ltd. 22,112 2 Wiseman 143929 2 Téléfiction Productions inc. 23,660 21 Thunder II 301723 N/A PMA Productions Inc. 33,369 Paperny Films Development (2) 40 Days at Sea I 146885 1 Inc. 46,500 422 (Le) I 144574 2 Blach Films Inc. 17,097 4Player I 146867 1 Sinking Ship Entertainment Inc. 51,806 5 Prochains (Les) III 146815 1 Gestion Avanti Ciné Vidéo Inc.