Hellas on Screen Hellas on Screen HABES 45 Alte Geschichte HABES – Band 45

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeric Time Travel Erwin F

Trinity University Digital Commons @ Trinity Classical Studies Faculty Research Classical Studies Department 7-2018 Homeric Time Travel Erwin F. Cook Trinity University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.trinity.edu/class_faculty Part of the Classics Commons Repository Citation Cook, E.F. (2018). Homeric time travel. Literary Imagination, 20(2), 220-221. doi:10.1093/litimag/imy065 This Post-Print is brought to you for free and open access by the Classical Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Trinity. It has been accepted for inclusion in Classical Studies Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Trinity. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Homeric Time Travel In a recent pair of articles I argued that the Odyssey presents itself as the heroic analogue to, or even substitute for, fertility myth.1 The return of Odysseus thus heralds the return of prosperity to his kingdom in a manner functionally equivalent to the return of Persephone, and with her of life, to earth in springtime. The first paper focused on a detailed comparison of the plots of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and the Odyssey;2 and the second on the relationship between Persephone’s withdrawal and return and the narrative device of ring-composition.3 In my analysis of ring-composition, I concluded that what began as a cognitive and functional pattern, organizing small-scale narrative structures, evolved into an aesthetic pattern, organizing large blocks of narrative, before finally becoming an ideological pattern, connecting the hero’s return to the promise of renewal offered by fertility myth and cult. -

Image – Action – Space

Image – Action – Space IMAGE – ACTION – SPACE SITUATING THE SCREEN IN VISUAL PRACTICE Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner (Eds.) This publication was made possible by the Image Knowledge Gestaltung. An Interdisciplinary Laboratory Cluster of Excellence at the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (EXC 1027/1) with financial support from the German Research Foundation as part of the Excellence Initiative. The editors like to thank Sarah Scheidmantel, Paul Schulmeister, Lisa Weber as well as Jacob Watson, Roisin Cronin and Stefan Ernsting (Translabor GbR) for their help in editing and proofreading the texts. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Copyrights for figures have been acknowledged according to best knowledge and ability. In case of legal claims please contact the editors. ISBN 978-3-11-046366-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-046497-9 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-046377-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956404 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche National bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Luisa Feiersinger, Kathrin Friedrich, Moritz Queisner, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com, https://www.doabooks.org and https://www.oapen.org. Cover illustration: Malte Euler Typesetting and design: Andreas Eberlein, aromaBerlin Printing and binding: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Inhalt 7 Editorial 115 Nina Franz and Moritz Queisner Image – Action – Space. -

An Ancient Theatre Dynasty: the Elder Carcinus, the Young Xenocles and the Sons of Carcinus in Aristophanes

Philologus 2016; 160(1): 1–18 Edmund Stewart* An Ancient Theatre Dynasty: The Elder Carcinus, the Young Xenocles and the Sons of Carcinus in Aristophanes DOI 10.1515/phil-2016-0001 Abstract: The elder Carcinus and his sons are mentioned, or appear on stage, as tragic performers in three plays by Aristophanes (Wasps, Clouds and Peace). They provide a unique insight into how the performance of tragedy could be (and frequently was) a family business. This study attempts to establish what can be known about this theatrical family from the evidence of comedy and how it functioned as an acting troupe. Moreover, in examining how the family troupe changed over time, we begin to learn more about the process by which one of Carcinus’ sons, Xenocles, was trained as a tragic poet. Though little is known about Carcinus, Xenocles was a relatively successful tragedian, who was active in the final two decades of the fifth century B.C. Both ancient and modern scholars have assumed that Xenocles was a poet by 422, when he is thought to have appeared as a character in the Wasps. I argue that Xenocles did not in fact make his debut as an independent poet until after 420. Before this date Aristophanes recognises Carcinus as the poet of the family company, which suggests that the young Xenocles was still serving his apprenticeship with his father at this time. Keywords: Aristophanes, Carcinus, Xenocles, tragedy, actors Introduction Theatre in the fifth century was often a family business. Sons, grandsons and other relations of tragedians frequently followed their forebears into a career in the theatre, either as actors or poets.1 The same was true of comic performers, though 1 See Sutton (1987) 11–9; Olson (2000) 69–70. -

4 | 2017 Volume 8 (2017) Issue 4 ISSN 2190-3387

4 | 2017 Volume 8 (2017) Issue 4 ISSN 2190-3387 Editorial: A Christmas Gift by Séverine Dusollier Designing Competitive Markets for Industrial Data – Between Propertisation and Access Law and Electronic Commerce Information Technology, Intellectual Property, Journal of by Josef Drexl From Cyberpunk to Regulation – Digitised Memories as Personal and Sensitive Data within the EU Data Protection Law by Krzysztof Garstka Copyright, Doctrine and Evidence-Based Reform by Stef van Gompel Non-Commercial Quotation and Freedom of Panorama: Useful and Lawful? by Eleonora Rosati Where is the Harm in a Privacy Violation? Calculating the Damages Afforded in Privacy Cases by the European Court of Human Rights by Bart van der Sloot Editors: Thomas Dreier Axel Metzger Gerald Spindler Lucie Guibault Miquel Peguera www.jipitec.eu Séverine Dusollier Chris Reed Karin Sein Journal of Intellectual Property, Information Technology and Electronic Commerce Law Table Of Contents Volume 8 Issue 4 December 2017 www.jipitec.eu [email protected] A joint publication of: Articles Prof. Dr. Thomas Dreier, M. C. J., KIT - Karlsruher Institut für Technologie, Zentrum für Angewandte Rechtswissenschaft (ZAR), Vincenz-Prießnitz-Str. 3, Editorial: A Christmas Gift 76131 Karlsruhe Germany by Séverine Dusollier 255 Prof. Dr. Axel Metzger, LL. M., Humboldt-Universität zu Designing Competitive Markets for Industrial Data – Between Berlin, Unter den Linden 6, Propertisation and Access 10099 Berlin by Josef Drexl 257 Prof. Dr. Gerald Spindler, Dipl.-Ökonom, Georg-August- From Cyberpunk to Regulation – Digitised Memories as Personal Universität Göttingen, and Sensitive Data within the EU Data Protection Law Platz der Göttinger Sieben 6, by Krzysztof Garstka 293 37073 Göttingen Copyright, Doctrine and Evidence-Based Reform Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, by Stef van Gompel 304 Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin and Georg-August-Universität Non-Commercial Quotation and Freedom of Panorama: Göttingen are corporations under Useful and Lawful? public law, and represented by their respective presidents. -

The Uses of Animation 1

The Uses of Animation 1 1 The Uses of Animation ANIMATION Animation is the process of making the illusion of motion and change by means of the rapid display of a sequence of static images that minimally differ from each other. The illusion—as in motion pictures in general—is thought to rely on the phi phenomenon. Animators are artists who specialize in the creation of animation. Animation can be recorded with either analogue media, a flip book, motion picture film, video tape,digital media, including formats with animated GIF, Flash animation and digital video. To display animation, a digital camera, computer, or projector are used along with new technologies that are produced. Animation creation methods include the traditional animation creation method and those involving stop motion animation of two and three-dimensional objects, paper cutouts, puppets and clay figures. Images are displayed in a rapid succession, usually 24, 25, 30, or 60 frames per second. THE MOST COMMON USES OF ANIMATION Cartoons The most common use of animation, and perhaps the origin of it, is cartoons. Cartoons appear all the time on television and the cinema and can be used for entertainment, advertising, 2 Aspects of Animation: Steps to Learn Animated Cartoons presentations and many more applications that are only limited by the imagination of the designer. The most important factor about making cartoons on a computer is reusability and flexibility. The system that will actually do the animation needs to be such that all the actions that are going to be performed can be repeated easily, without much fuss from the side of the animator. -

Annual Report 2004Shaw Television Broadcast Fund Shaw Television Broadcast Fund

Annual Report 2004Shaw Television Broadcast Fund Shaw Television Broadcast Fund 2004 Shaw Television Broadcast Fund 2004 was a milestone year at the Shaw Television Broadcast Fund, investing over $9.5 million in original Canadian children’s programming. We had a quantum leap in our funding Since 1998, the Fund has invested over enabling us to impact the children’s $35 million and supported 173 original television industry in a very big way productions. The Shaw Television Broadcast and we could not have done it without Fund is pleased to continue to finance the significant contributions from Shaw Canadian children’s television productions Communications, Star Choice Television based on their quality and innovation, Network and EastLink Cablesystems. As supported by a sound business plan. important and very key to our success this year, we welcomed two new contributors The success of this year is truly the start to Delta Cable Communications and Shaw something big for years to come. Pay Per View Ltd., a division of Shaw Cablesystems G.P. With the addition of our new contributors, we were able to increase our investments into the production of Canadian children’s and youth programming by 40% this year! 2004 Annual Report | 3 Investing in Canadian Children’s Television By Genre In Every Age Group Variety 6% Variety Magazine 3% Pre-School $2,707,500 Documentary 5% Primary (6-9) $452,800 Elementary (9-12) $4,397,950 Drama 86% Youth $1,218,650 Family $821,220 Across Canada British Columbia $397,200 Newfoundland $350,000 Nova Scotia $1,310,000 -

Klassics for Kids: the Reception of Antiquity in Children's

Klassics for Kids: The Reception of Antiquity in Children’s Entertainment Many, if not most, of today’s children will not get their first exposure to the ancient world from an ancient source, or even from a myth compendium like the justly famous D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths. Instead, they are more likely to meet people from Zeus to Caesar in their favorite picture book, Saturday morning cartoon, or PG rated movie. These sources are often what draws people to the Classics in the first place, and even more often provide the foundation of their understanding of the ancient world. Indeed, large numbers of students young and old are shocked to find that Ovid’s Hercules is not the same as the man they knew from Disney movies. Understanding antiquity’s status in the modern world therefore requires us to study the materials that craft the lens through which new generations will see it. This panel hopes to be a first step in that direction. Taking their cue from CAMWS’ recent thought provoking special panels on Classical Reception in Westerns, Sword and Sandal films, and other media, this panel will approach Greece and Rome’s role in children’s entertainment from both scholarly and pedagogical perspectives. The nature and significance of divergences from ancient sources will be discussed, as will strategies to maximize the benefits children’s television, books and films provide to the classroom while minimizing the potential problems they can cause. While this panel will be focused on children’s entertainment generally, the multiform nature of this entertainment provides a vantage point by which to combine multiple genres of reception analysis into a single panel. -

Movie Mirror Book

WHO’S WHO ON THE SCREEN Edited by C h a r l e s D o n a l d F o x AND M i l t o n L. S i l v e r Published by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., I n c . NEW YORK CITY t y v 3. 67 5 5 . ? i S.06 COPYRIGHT 1920 by ROSS PUBLISHING CO., Inc New York A ll rights reserved | o fit & Vi HA -■ y.t* 2iOi5^ aiblsa TO e host of motion picture “fans” the world ovi a prince among whom is Oswald Swinney Low sley, M. D. this volume is dedicated with high appreciation of their support of the world’s most popular amusement INTRODUCTION N compiling and editing this volume the editors did so feeling that their work would answer a popular demand. I Interest in biographies of stars of the screen has al ways been at high pitch, so, in offering these concise his tories the thought aimed at by the editors was not literary achievement, but only a desire to present to the Motion Picture Enthusiast a short but interesting resume of the careers of the screen’s most popular players, rather than a detailed story. It is the editors’ earnest hope that this volume, which is a forerunner of a series of motion picture publications, meets with the approval of the Motion Picture “ Fan” to whom it is dedicated. THE EDITORS “ The Maples” Greenwich, Conn., April, 1920. whole world is scene of PARAMOUNT ! PICTURES W ho's Who on the Screcti THE WHOLE WORLD IS SCENE OF PARAMOUNT PICTURES With motion picture productions becoming more masterful each year, with such superb productions as “The Copperhead, “Male and Female, Ireasure Island” and “ On With the Dance” being offered for screen presentation, the public is awakening to a desire to know more of where these and many other of the I ara- mount Pictures are made. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

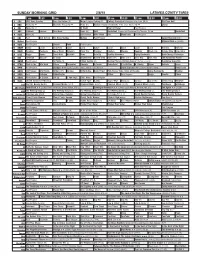

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

The Cambridge Companion to Hippocrates Edited by Peter E. Pormann Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-06820-9 — The Cambridge Companion to Hippocrates Edited by Peter E. Pormann Index More Information Index abortion, 172–5, 278, 377 Articella, 46 Achilles, 9, 71, 150 Asclepius, 240, 317, 341, 378 Aephicianus, 300, 301 Asulanus Aeschylus, 122, 214 editio princeps,31 aetiology, 4, 89–118, 185, 193–4 Avempace, 355 Aëtius of Amida, 18, 60 Avicenna, 343 Agamemnon, 9 Canon of Medicine, 47, 347, 357 Alcmaeon of Croton, 23, 80, 90, 100, 135 encephalocentric theory, 124 Bacchius of Tanagra, 29, 43, 293 Alexander of Tralles, 18, 60, 315 Bacon, Francis, 21, 369–71 Alexander the Great, 61 Baġdā dī, ʿAbd al-Laṭīf al-, 355, 356–7 Alexandria, 45, 305, 340 Bartholomew of Messina, 47 Alexandrian Renaissance, 45, 60, 322 Biṭrīq, al-, 350 exegesis, 239 bladder, 74, 240 library, 42, 293 diseases, 196 allopathy, 13, 96, 205, 210, 212 bloodletting, 35 amulets, 139, 209, 213 body-mind interface, 3 anaesthesia, 15, 224 brain, 77, 98, 125 anatomy, 3 Burgundio of Pisa, 47 in Galenic doctorine, 305–6 in medieval Europe, 367 Calvus, 31 Anaxagoras, 135, 150 Cassius Felix, 315 Anaximander, 90 cauterisation, 35, 142, 168, 226, 260, 262 Andromachus, 43, 293 Celsus, 27, 318, 322 animals, 112, 223, 336 On Medicine, 175, 202, 217, 219 classification, 131–2 surgery, 217, 242 Apollo, 25, 26, 71, 81, 170, 171, 174, 214 cheese, 109, 112, 137 Apollonius of Citium, 42, 43, 44, 59, 293, 294 childbirth, 251 Arabic, xiii, 19, 44, 48 contraception, 277 translation movement, 348–52 Cornarius, 31 Aretaeus of Cappadocia, 197, 293 Corpus Medicorum -

Appre Hender Les Personnages En 3D : Quelques Principes Fondamentaux Du Rig

Universite Paris 8 Master Arts Mention : Arts Plastiques et Art Contemporain Spe cialite : Arts et Technologies de l'Image Virtuelle Appre hender les personnages en 3D : quelques principes fondamentaux du rig Rodolphe Zirah Me moire de Master 2 2013- 2014 Résumé Le rig est un enjeu majeur de la production des films d’animation en images de synthèse d’aujourd’hui, tout en étant caché dans l’ombre du travail de l’animateur. Pourtant, pour qu’une animation soit réussie, il faut que le rig soit bien pensé. Il faut donc créer son rig en pensant à rendre le travail des animateurs plus simple et intuitif, et certains choix du riggeur peuvent influencer fortement sur la qualité de l’animation et sur le temps de production. Cette étude se découpe en trois parties. Nous commencerons pas un état de l’art bref qui nous montrera que le rig existe bien avant la 3D, avec les créatures en volume de toutes l’histoire du cinéma d’animation. Nous discuterons ensuite de technique de rig à proprement parler. Nous donnerons, dans une deuxième partie, les principes fondamentaux nécessaires à la bonne compréhension et à la bonne réalisation d’un rig, en général. Puis nous détaillerons, dans une troisième partie, des cas particuliers de rig - personnage mécanique et rig facial- à partir d’étude de productions. On utilisera Maya (2013) comme outil principal. Abstract Nowadays, character rigging is one of major issue of animated films, while hidden in the shadow of animation work. Yet, for a movie to be successful it is necessary that the rig is well thought out. -

2012 Annual Report

2012 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA/ONSTAGE Events ................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Special Screenings .................................................................................................................................... 23 Robert M.