Klassics for Kids: the Reception of Antiquity in Children's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2004Shaw Television Broadcast Fund Shaw Television Broadcast Fund

Annual Report 2004Shaw Television Broadcast Fund Shaw Television Broadcast Fund 2004 Shaw Television Broadcast Fund 2004 was a milestone year at the Shaw Television Broadcast Fund, investing over $9.5 million in original Canadian children’s programming. We had a quantum leap in our funding Since 1998, the Fund has invested over enabling us to impact the children’s $35 million and supported 173 original television industry in a very big way productions. The Shaw Television Broadcast and we could not have done it without Fund is pleased to continue to finance the significant contributions from Shaw Canadian children’s television productions Communications, Star Choice Television based on their quality and innovation, Network and EastLink Cablesystems. As supported by a sound business plan. important and very key to our success this year, we welcomed two new contributors The success of this year is truly the start to Delta Cable Communications and Shaw something big for years to come. Pay Per View Ltd., a division of Shaw Cablesystems G.P. With the addition of our new contributors, we were able to increase our investments into the production of Canadian children’s and youth programming by 40% this year! 2004 Annual Report | 3 Investing in Canadian Children’s Television By Genre In Every Age Group Variety 6% Variety Magazine 3% Pre-School $2,707,500 Documentary 5% Primary (6-9) $452,800 Elementary (9-12) $4,397,950 Drama 86% Youth $1,218,650 Family $821,220 Across Canada British Columbia $397,200 Newfoundland $350,000 Nova Scotia $1,310,000 -

Happily Ever Ancient

HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media HAPPILY EVER ANCIENT This work is subject to an International Creative Commons License Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0, for a copy visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Visions of Antiquity for children in visual media First Edition, December 2020 ...still facing COVID-19. Editor: Asociación para la Investigación y la Difusión de la Arqueología Pública, JAS Arqueología Plaza de Mondariz, 6 28029 - Madrid www.jasarqueologia.es Attribution: In each chapter Cover: Jaime Almansa Sánchez, from nuptial lebetes at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece. ISBN: 978-84-16725-32-8 Depósito Legal: M-29023-2020 Printer: Service Pointwww.servicepoint.es Impreso y hecho en España - Printed and made in Spain CONTENTS INTRODUCTION: A CONTEMPORARY ANTIQUITY FOR CHILDREN AND YOUNG AUDIENCES IN FILMS AND CARTOONS Julián PELEGRÍN CAMPO 1 FAMILY LOVE AND HAPPILY MARRIAGES: REINVENTING MYTHICAL SOCIETY IN DISNEY’S HERCULES (1997) Elena DUCE PASTOR 19 OVER 5,000,000.001: ANALYZING HADES AND HIS PEOPLE IN DISNEY’S HERCULES Chiara CAPPANERA 41 FROM PLATO’S ATLANTIS TO INTERESTELLAR GATES: THE DISTORTED MYTH Irene CISNEROS ABELLÁN 61 MOANA AND MALINOWSKI: AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH TO MODERN ANIMATION Emma PERAZZONE RIVERO 79 ANIMATING ANTIQUITY ON CHILDREN’S TELEVISION: THE VISUAL WORLDS OF ULYSSES 31 AND SAMURAI JACK Sarah MILES 95 SALPICADURAS DE MOTIVOS CLÁSICOS EN LA SERIE ONE PIECE Noelia GÓMEZ SAN JUAN 113 “WHAT A NOSE!” VISIONS OF CLEOPATRA AT THE CINEMA & TV FOR CHILDREN AND TEENAGERS Nerea TARANCÓN HUARTE 135 ONCE UPON A TIME IN MACEDON. -

DHX Media Ltd

A YEAR OF MILESTONES July 2007 November 2007 March 2008 Secured the worldwide television Issued 9,815,000 Units from Production began for Kid vs. Kat and home entertainment treasury at $1.80 per unit for total Season I, Animal Mechanicals distribution rights to My Spy Family. proceeds of $17,667,000. A Unit Season II, Canada’s Super Spellers consisted of one common share and Season I and Poppets Town Season August 2007 one-half of one common share I. Signed up a UK licensing agent for purchase warrant. Franny’s Feet. Canada’s Super Spellers launched Completed a strategic investment in online qualifying website. This Hour Has 22 Minutes Season Tribal Nova, an on-line game XIV was nominated for 4 Gemini developer and operator of gaming Acquired Halifax-based Bulldog Awards. and video-on-demand broadband Interactive Fitness Inc., a developer channels for children. of children’s entertainment centers. September 2007 Posted year end results for 2007 December 2007 April 2008 with revenues up 65%. Acquired Vancouver-based Studio B Signed a Canadian-Singaporean Productions Inc. with a library of collaboration with Scrawl Studios for Award-winning hit comedy series 400 half-hours of children’s new animated series RPG High. This Hour Has 22 Minutes returned programming and a current for its 15th season. production slate of seven shows The Guard was renewed for a including Kid vs. Kat for YTV, Ricky second season by Global Television. Production began on The Guard Sprocket – Showbiz Boy for Season I. Teletoon and Nickelodeon Networks May 2008 and Martha Speaks, a co-production Canada’s Super Spellers began local Shake Hands with the Devil with WGBH Boston. -

Spiritual Odysseys in Children's Television

Spiritual Odysseys in Children’s Television The story of Odysseus’ wanderings is part of North American story telling to the point that it can be classified as modern folklore. (Hardwick 2007). Although other aspects of Homer’s Odyssey, such as the Telemachiad and the Phaeacians, have fallen by the wayside, the dangers, temptations, and adventures that Odysseus encounters on his journey home are interwoven throughout much of children’s literature (Norton 2003, Huck & Kiefer 2004). Unsurprising, visually appealing encounters with sirens, Cyclopes, and sentient whirlpools often appear in children’s television. However, these exciting encounters are only the superficial focus of their stories. Instead, children’s television often transforms the myth of Odysseus’ journey into a journey of personal growth for the shows’ young protagonists. It is not uncommon for televised adaptations of the wanders of Odysseus to relegate Odysseus to a secondary role or outright replace him with a younger character. To give a few examples, Duck Tales’ episode “Homer Sweet Homer” sends Odysseus’s nephew, Homer, to retrace his famous relative’s steps with the help of the McDuck family, and Odie, a descended of Odysseus in Class of the Titans, encounters Calypso, Scylla, and Aeolus in the episode “Odie- sey.” These youthful characters act as stand-ins for the young viewers. As a result, Odysseus becomes older relative or father-figure to the young travelers and an object of inspiration. As the heroes make their journeys, they also struggle with their own personal feelings of weakness, failure, or inferiority and aspire to match Odysseus’ accomplishments. Rather than exploring all instances of this phenomenon, the paper will seek to illuminate the personal growth aspects of Television Odysseys through one example, an episode of Martha Speaks called “Truman and the Deep Blue Sea.” Martha Speaks is a television show aimed at children from ages 4 to 7. -

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT ("Agreement")

-·- ·· -·--- ---------- INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT ("Agreement") covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the "Guild") and The CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION ("CFTPA") and THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TELJ~:VISION DUQUEBEC ("APFTQ") (the "Associations") January 1, 2010 to December 31, 20 II © 2010 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION AND THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TELEVISION DU QUEBEC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General -AU Productions p. Article AI Recognition, Application and Term p. Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 16 Article AS Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p.22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p.24 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p.29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article AIO Security for Payment p.42 Article All Payments p.44 Article Al2 Administration Fee p.52 Article Al3 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer's Fees p. 52 Article Al4 Contributions and Deductions from Writer's Fees in the case of Waivers p.54 Section 8: Conditions Governing Engagement p.55 Article 81 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p.55 Article 82 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 61 Article 83 Options p.62 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p.63 Article Cl Feature Film p.63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. -

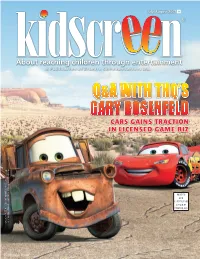

Q&A with Thq's Gary Rosenfeld

US$7.95 in the U.S. CA$8.95 in Canada US$9.95 outside of CanadaJuly/August & the U.S. 2007 1 ® Q&A WITH THQ’S GARY ROSENFELD CCARSARS GGAINSAINS TTRACTIONRACTION IINN LLICENSEDICENSED GGAMEAME BBIZIZ NUMBER 40050265 40050265 NUMBER ANADA USPS Approved Polywrap ANADA AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA C IN PRINTED 001editcover_July_Aug07.indd1editcover_July_Aug07.indd 1 77/19/07/19/07 77:00:43:00:43 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 2 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:05:06:05 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 3 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:54:06:54 PMPM #8#+.#$.'019 9 9 Animation © Domo Production Committee. Domo © NHK-TYO 1998. [ZVijg^c\I]ZHiVg<^gah Star Girls and Planet Groove © Dianne Regan Sean Regan. XXXCJHUFOUUW K<C<M@J@FEJ8C<J19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'(2\dX`c1iZfcc`ej7Y`^k\ek%km C@:<EJ@E>GIFDFK@FEJ19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'-2\dX`c1idXippXe\b7Y`^k\ek%km KKS4548.BIGS4548.BIG TTENT.inddENT.indd 2 77/19/07/19/07 66:54:45:54:45 PMPM 1111 F3 to mine MMOG space for TV concepts 114Parthenon4 Kids: Geared up and ready to invest 1177 Will Backseat TV boost Nick’s in-car profile? 225Storm Hawks5 goes jjuly/augustuly/august viral with Guerilla 0077 HHighlightsighlights ffromrom tthishis iissuessue 10 up front 24 marketing France TV to invest in Chrysler and Nick hope more content and global to get more mileage out Special Reports web presence of the minivan set with 29 RADARSCREEN backseat TV feature Fred Seibert’s Frederator Films 13 ppd tries a fresh approach to Parthenon Kids offers 26 digital -

British Columbia Film Commission Production Statistics 2007 2007 Shot in Bc Totals

BRITISH COLUMBIA FILM COMMISSION PRODUCTION STATISTICS 2007 2007 SHOT IN BC TOTALS TOTAL PRODUCTIONS # % Total Budget Overall Total Spent In BC % Features/DVD Features 47 24% $ 428,322,558 $ 260,784,365 28% TV Series 42 21% $ 622,559,767 $ 435,120,166 46% Movies of the Week 43 22% $ 104,126,297 $ 92,401,686 10% TV Pilots 7 3% $ 23,626,584 $ 16,357,584 2% Mini Series 3 1% $ 50,704,493 $ 35,057,893 3% Documentaries 32 16% $ 18,706,755 $ 14,707,472 2% Short Films 9 4% $ 245,500 $ 245,500 0% Animation 19 9% $ 118,639,789 $ 88,673,149 9% Total 202 100% $ 1,366,931,743 $ 943,347,815 100% DOMESTIC PRODUCTIONS # % Total Budget Overall Total Spent In BC % Features/DVD Features 24 17% $ 84,509,508 $ 81,609,894 20% TV Series 24 17% $ 168,041,039 $ 157,641,573 39% Movies of the Week 36 26% $ 83,378,067 $ 74,445,538 18% TV Pilots 1 1% $ 769,584 $ 764,584 0% Mini Series 2 1% $ 34,386,993 $ 24,357,893 6% Documentaries 32 23% $ 18,706,755 $ 14,707,472 4% Short Films 9 7% $ 245,500 $ 245,500 0% Animation 10 8% $ 70,036,361 $ 53,932,027 13% 138 100% $ 460,073,807 $ 407,704,481 100% FOREIGN PRODUCTIONS # % Total Budget Overall Total Spent In BC % Features/DVD Features 23 36% $ 343,813,050 $ 179,174,471 33% TV Series 18 28% $ 454,518,728 $ 277,478,593 52% Movies of the Week 7 11% $ 20,748,230 $ 17,956,148 3% TV Pilots 6 9% $ 22,857,000 $ 15,593,000 3% Mini Series 1 2% $ 16,317,500 $ 10,700,000 2% Documentaries 0 0% $ 0 $ 0 0% Short Films 0 0% $ 0 $ 0 0% Animation 9 14% $ 48,603,428 $ 34,741,122 7% 64 100.00% $ 906,857,936 $ 535,643,334 100% FACTSHEET BRITISH -

(“Agreement”) Covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CMPA”) and ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE (“AQPM”) (the “Associations”) March 16, 2015 to December 31, 2017 © 2015 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION and the ASSOCIATION QUÉBÉCOISE DE LA PRODUCTION MÉDIATIQUE. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 15 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 23 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 41 Article A11 Payments p. 43 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 50 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 51 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 53 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 54 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 54 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 60 Article B3 Options p. 61 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. 63 Article C1 Feature Film p. 63 Article C2 Optional Incentive Plan for Feature Films p. 66 Article C3 Television Production (Television Movies) p. -

MICHAEL RICHARD PLOWMAN, Composer for Film, Television & Games

MICHAEL RICHARDfish-fry PLOWMAN music & sound composers for film & television composer for film, television & Games Contact: ARI WISE, agent • 1.866.784.3222 • [email protected] Contact: ARI WISE, agent • 1.866.784.3222 • [email protected] ANIMATED MOVIES FRANK AND ZED (feature) 2020 Evan Bailey, Jesse Blanchard, prod Puppetcore Film Jesse Blanchard, dir. BALOON GIRL (short) 2018 Shabnam Rezaei, Aly Jetha, Daniel Errico, prod Big Bad Boo Studios E. Soriano, dir. PIXI POST & THE GIFT BRINGERS (theatrical feature) 2016 Juanjo Elordi, Felipe Morell, E. Gozalo, L. Barreto, prod. Somuga, Bitebilau, Digitz Films, EITB, Sola Media Gork Sesma, dir. GHOST PATROL (TV movie) 2016 L. K. Lunsford, A. Loi, J. Netter, J. Sherba, H. Puttock prod. DHX Media, Disney Channel, The Family Channel Karen J. Lloyd, dir. BOB’S BROKEN SLEIGH (TV movie) 2015 L.K. Lunsford, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, prod. Eh-Okay Prods., Disney Channel, The Family Channel Jay Surridge, dir. FROZEN IN TIME (TV movie) 2014 J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, S. Shear, prod. Kickstart Productions, Ketnet Alex Leung, dir. UNDER WRAPS (TV movie) 2014 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, prod. Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent. Gordon Crum, dir. THE NAUGHTY LIST (TV movie) 2013 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, T. Moore, Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent., Raindance Ent. S. Shear, prod., Gordon Crum, Jay Surridge, dir. A MONSTEROUS HOLIDAY (TV movie) 2013 T. Drinkwater, J. Netter, S. Norkin, H. Puttock, T. Moore, Kickstart Productions, ARC Ent., Cartoon Network S. Shear, prod., Gordon Crum, dir. ABONIMABLE CHRISTMAS (TV movie) 2012 T. -

AGREEMENT (“Agreement”)

INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CFTPA”) and THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TÉLÉVISION DU QUÉBEC (“APFTQ”) (the “Associations”) ***VERSION WITH 2009 RATES FOR WGC WEBSITE USE ONLY*** November 19, 2006 to December 31, 2008 EXTENDED TO DECEMBER 31, 2009 © 2006 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN FILM AND TELEVISION PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION AND THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TÉLÉVISION DU QUÉBEC. 10940 (06) TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 16 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 22 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 24 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 42 Article A11 Payments p. 44 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 52 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 52 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 54 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 55 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 55 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 61 Article B3 Options p. 62 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p. -

Michael Plowman Composer Profile

LONDON - LOS ANGELES - VANCOUVER Biography: For the past 25 years, London, Los Angeles based composer Michael Richard Plowman has been composing award winning and internationally recognized music, touching audiences in over 120 countries. His passion for creativity began in his birthplace of England where he learned to play the trumpet at the early age of three. Plowman's love and talent of music quickly grew, as did his aspirations. He began teaching himself different orchestral instruments. Over the course of his school years, Plowman was a member of jazz and rock groups, playing gigs at local clubs, and at 14 landed his first commercial television job. At 16 he received a recording contract and produced his first album, "The Now Sounds of Today". Plowman continued his musical training at universities in both Canada and the United States. He began conducting and touring worldwide with various orchestras and choirs, then moved into theatre, and finally into composing for Film, Television & Games. He works with many of the major players in the industry world wide; including Sony Pictures Television, BBC, Cartoon Network, WB, 20th Century Fox, New Line Cinema, MTV, Nickelodeon, A&E, Discovery, Animal Planet to name a few. "Working in film, television and games has given me the opportunity to explore many new musical styles and techniques," says Plowman. "Every production is unique and providing an original score is essential." With over 500 credits to date in live-action, animation, film, concert works and games Plowman continues to create symphonic adventures in his own style for the absolute entertainment experience. -

512-17312-14 (851-0034-14)

IPA cover_12-14:ipa cover03.final 11/30/12 10:54 AM Page 1 IPA 2012-2014Effective November 1, 2012 Writers Independent Production Agreement INDEPENDENT PRODUCTION AGREEMENT (“Agreement”) covering FREELANCE WRITERS of THEATRICAL FILMS TELEVISION PROGRAMS and OTHER PRODUCTION between The WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA (the “Guild”) and The CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION (“CMPA”) and THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TÉLÉVISION DU QUÉBEC (“APFTQ”) (the “Associations”) November 1, 2012 to December 31, 2014 © 2012 WRITERS GUILD OF CANADA and CANADIAN MEDIA PRODUCTION ASSOCIATION AND THE ASSOCIATION DES PRODUCTEURS DE FILMS ET DE TÉLÉVISION DU QUÉBEC. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A: General – All Productions p. 1 Article A1 Recognition, Application and Term p. 1 Article A2 Definitions p. 4 Article A3 General Provisions p. 14 Article A4 No Strike and Unfair Declaration p. 16 Article A5 Grievance Procedures and Resolution p. 16 Article A6 Speculative Writing, Sample Pages and Unsolicited Scripts p. 23 Article A7 Copyright and Contracts; Warranties, Indemnities and Rights p. 24 Article A8 Story Editors and Story Consultants p. 29 Article A9 Credits p. 30 Article A10 Security for Payment p. 42 Article A11 Payments p. 44 Article A12 Administration Fee p. 51 Article A13 Insurance and Retirement Plan, Deductions from Writer’s Fees p. 53 Article A14 Contributions and Deductions from Writer’s Fees in the case of Waivers p. 54 Section B: Conditions Governing Engagement p. 55 Article B1 Conditions Governing Engagement for all Program Types p. 55 Article B2 Optional Bibles, Script/Program Development p. 61 Article B3 Options p. 62 Section C: Additional Conditions and Minimum Compensation by Program Type p.