Content Warning and Disclaimer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Philosophical Inquiry Into the Development of the Notion of Kalos Kagathos from Homer to Aristotle

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theses 2006 A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle Geoffrey Coad University of Notre Dame Australia Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses Part of the Philosophy Commons COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA Copyright Regulations 1969 WARNING The material in this communication may be subject to copyright under the Act. Any further copying or communication of this material by you may be the subject of copyright protection under the Act. Do not remove this notice. Publication Details Coad, G. (2006). A philosophical inquiry into the development of the notion of kalos kagathos from Homer to Aristotle (Master of Philosophy (MPhil)). University of Notre Dame Australia. https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theses/13 This dissertation/thesis is brought to you by ResearchOnline@ND. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of ResearchOnline@ND. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PHILOSOPHICAL INQUIRY INTO THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE NOTION OF KALOS KAGATHOS FROM HOMER TO ARISTOTLE Dissertation submitted for the Degree of Master of Philosophy Geoffrey John Coad School of Philosophy and Theology University of Notre Dame, Australia December 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iv Declaration v Acknowledgements vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: The Fish Hook and Some Other Examples 6 The Sun – The Source of Beauty 7 Some Instances of Lack of Beauty: Adolf Hitler and Sharp Practices in Court 9 The Kitchen Knife and the Samurai Sword 10 CHAPTER 2: Homer 17 An Historical Analysis of the Phrase Kalos Kagathos 17 Herman Wankel 17 Felix Bourriott 18 Walter Donlan 19 An Analysis of the Terms Agathos, Arete and Other Related Terms of Value in Homer 19 Homer’s Purpose in Writing the Iliad 22 Alasdair MacIntyre 23 E. -

Folktale Types and Motifs in Greek Heroic Myth Review P.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic Quest

Mon Feb 13: Heracles/Hercules and the Greek world Ch. 15, pp. 361-397 Folktale types and motifs in Greek heroic myth review p.11 Morphology of the Folktale, Vladimir Propp 1928 Heroic quest NAME: Hera-kleos = (Gk) glory of Hera (his persecutor) >p.395 Roman name: Hercules divine heritage and birth: Alcmena +Zeus -> Heracles pp.362-5 + Amphitryo -> Iphicles Zeus impersonates Amphityron: "disguised as her husband he enjoyed the bed of Alcmena" “Alcmena, having submitted to a god and the best of mankind, in Thebes of the seven gates gave birth to a pair of twin brothers – brothers, but by no means alike in thought or in vigor of spirit. The one was by far the weaker, the other a much better man, terrible, mighty in battle, Heracles, the hero unconquered. Him she bore in submission to Cronus’ cloud-ruling son, the other, by name Iphicles, to Amphitryon, powerful lancer. Of different sires she conceived them, the one of a human father, the other of Zeus, son of Cronus, the ruler of all the gods” pseudo-Hesiod, Shield of Heracles Hera tries to block birth of twin sons (one per father) Eurystheus born on same day (Hera heard Zeus swear that a great ruler would be born that day, so she speeded up Eurystheus' birth) (Zeus threw her out of heaven when he realized what she had done) marvellous infancy: vs. Hera’s serpents Hera, Heracles and the origin of the MIlky Way Alienation: Madness of Heracles & Atonement pp.367,370 • murders wife Megara and children (agency of Hera) Euripides, Heracles verdict of Delphic oracle: must serve his cousin Eurystheus, king of Mycenae -> must perform 12 Labors (‘contests’) for Eurystheus -> immortality as reward The Twelve Labors pp.370ff. -

Hesiod Theogony.Pdf

Hesiod (8th or 7th c. BC, composed in Greek) The Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, are probably slightly earlier than Hesiod’s two surviving poems, the Works and Days and the Theogony. Yet in many ways Hesiod is the more important author for the study of Greek mythology. While Homer treats cer- tain aspects of the saga of the Trojan War, he makes no attempt at treating myth more generally. He often includes short digressions and tantalizes us with hints of a broader tra- dition, but much of this remains obscure. Hesiod, by contrast, sought in his Theogony to give a connected account of the creation of the universe. For the study of myth he is im- portant precisely because his is the oldest surviving attempt to treat systematically the mythical tradition from the first gods down to the great heroes. Also unlike the legendary Homer, Hesiod is for us an historical figure and a real per- sonality. His Works and Days contains a great deal of autobiographical information, in- cluding his birthplace (Ascra in Boiotia), where his father had come from (Cyme in Asia Minor), and the name of his brother (Perses), with whom he had a dispute that was the inspiration for composing the Works and Days. His exact date cannot be determined with precision, but there is general agreement that he lived in the 8th century or perhaps the early 7th century BC. His life, therefore, was approximately contemporaneous with the beginning of alphabetic writing in the Greek world. Although we do not know whether Hesiod himself employed this new invention in composing his poems, we can be certain that it was soon used to record and pass them on. -

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife

Eris and Epos Composition, Competition, and the Domestication of Strife Joel P. Christensen Brandeis University [email protected] Abstract This article examines the development of the theme of eris in Hesiod and Homer. Start- ing from the relationship between the destructive strife in the Theogony (225) and the two versions invoked in the Works and Days (11–12), I argue that considering the two forms of strife as echoing zero and positive sum games helps us to identify the cultural and compositional force of eris as cooperative competition. After establishing eris as a compositional theme from the perspective of oral poetics, I then argue that it develops from the perspective of cosmic history, that is, from the creation of the universe in Hes- iod’s Theogony through the Homeric epics and into its double definition in the Works and Days.To explore and emphasize how this complementarity is itself a manifestation of eris, I survey its deployment in our major extant epic poems. Keywords eris – competition – conflict – poetics – rivalry In Cypria fr. 1, Zeus fans “the flames of the great strife of the Trojan war / to lighten the [earth’s] burden with death” (ῥιπίσσας πολέμου μεγάλην ἔριν Ἰλιακοῖο, 5).* Similarly, in Hesiod (fr. 204 M-W), when strife divides the gods at the birth of Hermione—“all the gods were of two minds / because of the strife” (πάν- τες δὲ θεοὶ δίχα θυμὸν ἔθεντο / ἐξ ἔριδος, 94–95)—Zeus hastens the destruction of the Heroes: “And then he hastened to extinguish the great race of human * A version of this article was given at the Heartland Graduate Conference in Ancient Stud- ies at the University of Missouri in 2015. -

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; Proquest Pg

The Name of Penelope Whallon, William Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Jan 1, 1960; 3, 2; ProQuest pg. 57 The Name of Penelope William W hallon T HE TALE OF ODYSSEUS' RETURN would have been very different if his wife had not been known as Penelope. For the Homeric poems came from an age of aural etymologizing,l the minstrels who perfected the poems throughout centuries of storytelling found proper nouns as meaningful as common nouns, and certain phonetic associations at first fortuitous became inevitable. Shakespeare's Juli et by any other name than Capulet would have had greater fortune in love, but Penelope's name is even more vitally related to her biography. Now it is an obvious fact that a language built upon a rather small number of phonemes is almost necessarily going to include homonyms, and correspondence of sound alone is insufficient to indicate words as cognate. In present-day Norwegian, for example, the word for the duck, Anda (where the dental stop is no longer pronounced), does not compel any kind of dark reminiscence of the girl named Anna, and likewise the duck 7TTJVEAoljl need not be thought germane to Penelope,2 unless in the similarity there is a remnant from the dawn of time, when in a beast epic Penelope might actually have been a duck, Athene an owl, Hera a heifer, and Apollo a wolf. In the Homeric poems we possess, the 7TTJv€Aoljl and Penelope have no semantic relationship, and the coincidence of identical syllables is unimportant. Another word, however, has been commonly observed as apparently akin to the name of Pe nelope, and may have had a crucial bearing upon her career: this IMost notably in Od. -

Prof. Thomas Hubbard Office

Prof. Thomas Hubbard Office: WAG 9 Hours: TTh 1-1:30, F 1-3 Phone: 471-0676 E-mail: [email protected] TAs: Colin MacCormack ([email protected]) & Tim Corcoran ([email protected]) TA office hours by appointment SYLLABUS - CLASSICAL MYTHOLOGY (CC 303 - #32145) The purpose of this course is to familiarize students in depth with the major myths of Ancient Greece, which have proven so influential on art, literature, and popular imagination in Rome, Renaissance and Baroque Europe, and even the contemporary world. We shall examine the various cultural influences that shaped and transformed these stories, as well as the way that gods and heroes were embedded in religious cult and ritual. Students will also be afforded the opportunity to learn about major theories of interpretation. The format of the course will center around daily lectures, but questions and discussion are encouraged. This course carries the Global Cultures flag. Global Cultures courses are designed to increase your familiarity with cultural groups outside the United States. You should therefore expect a substantial portion of your grade to come from assignments covering the practices, beliefs, and histories of at least one non-U.S. cultural group, past or present. PART ONE: THE OLYMPIAN GODS Aug. 27 - "The Nature of Myths and their Interpretation: The Case of the Greeks" Sept. 1 - "Who Were the Greeks?" Reading: Csapo, Theories (pp. 1-36) Sept. 3 - "Myths of Creation and Cosmogony" Reading: Hesiod, Theogony (pp. 61-75); Handbook: Uranus, Ge, Cronus, Rhea, Atlas, Titans, Giants, Cyclopes, Hundred-handed Sept. 8 - "Zeus and the Establishment of Power" Reading: Hesiod, Theogony (pp. -

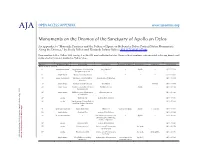

Supplemental Content: Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary Of

AJA OPEN ACCESS: APPENDIX www.ajaonline.org Monuments on the Dromos of the Sanctuary of Apollo on Delos An appendix to “Honorific Practices and the Politics of Space on Hellenistic Delos: Portrait Statue Monuments Along the Dromos,” by Sheila Dillon and Elizabeth Palmer Baltes (AJA 117 [2013] 207–46). Base numbers follow Vallois 1923 (see fig. 3 in the AJA print-published article). Bases without numbers were recorded as having been found in the area but were not marked on Vallois’ plan. Base No. Monument Type Honorand(s) Dedicator(s) Reason(s) for Honor Dedicated to Sculptor(s) Reference(s) Bases set up ca. 250–200 5 equestrian statue Epigenes, son of Andron, the King Attalos I – Apollo – IG 11 4 1109 Pergamene general 8 single statue Donax, son of Apollonios – – – – IG 11 4 1202 16 group monument Aischylo(. .) and his father, Mennis, son of Nikarchos – – – IG 11 4 1168 Nikarchos 19 single statue female, Hellenistic queen? the Delians – – Thoinias IG 11 4 1088 20 single statue Autokles, son of Ainesidemos, Autokles, his son – Apollo – IG 11 4 1194 from Chalcidia 117.2) 25 single statue Phildemos, son of Pythermos Eumedes, his son – – – IG 11 4 1193 of Chalcedon 27 exedra family group demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1090 33 exedra family group of Jason, Eukleia, – – – – IG 11 4 1203 Timokleia, Straton, Timokleia, Sillis 41 victory monument Gallic dedication Attalos I(?) victory over Gauls Apollo (. .)epoiei IG 11 4 1110 50c single statue Aichmokritos demos of the Delians – – – IG 11 4 1094 American Journal of Archaeology American 53 -

MYTHS R, 44ORSE 'MYTHOLOGY ANNA

NOS0-430 ERIC REPORT RESUME ED 010 139 1 a.09.0.67 24 QRE VI NYTHS,..*LAI MATURE ORR ICULUM: STUDENT VERS IOU. it I TZH ABER RaR60230', &.14IVERS ITV OF mesa* =MESE CRP -Pi 449-10 RR- 5.11360-v40 ..45 ED itS C E MP'S Os 13 HC..424i60 cop it SEVENTH GRADE, *STUDY -GUIDES, *CURRIE Cdi.UN GUIDES, -*LITERATURE* *NYTHOLOGY. - ENGLISH C URRI GUM. -LITERATURE PROGRAMS EUGENE, OREGON PROJECT ENGL. UN, NB4 GRAMMAR PRESENTED- HERE WM A ,STUDY t-S_VI OE: FOR.STUDENT USE; A .-SEWENTHGRADE L/ TER ATUR E CURRI CULUNT I NTROOUCTOLir XATER/AL los PaesENTE0 ON GREEK MYTHS r, 44ORSE 'MYTHOLOGY ANNA :. AMERICAN INDIAN r prIfiquisfeatsivoir GUEST IONS SUGGESTED A CT I VItIES9 AND Ass REFERENCE soft of PITIliS VritE PRESENTED. AN ACCONIANY-INS *GUIDE WAS PREPARED FOR TEACfrIERS EL) 010 140I e: UN/ .0) rave:t e PT.PARThMIT EnUCI1.11%; ante wet rA.RE Office of Education mils document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organ:zat:on originating it. Points of view or .op':nions stated do not necessarily represent official -Office of Education position or policy. OREGON CURRICULUM,. STUDY CENTER Trri-S"lir" in 11.3 Literature Curriculum I Studait Version The project reported heksinwas supported through the Cooperative Research Program ofthe Office of Education, U, S. Department of Health,Education, and Welfare. 4 4 r 7777*,\C 1,,IYTHS General. Introduction How was the world made? Where did the first people live? Why are we here? To all of these questions people have sought answers for thousands of years. -

Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: a Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas

The Internet Journal of Forensic Science ISPUB.COM Volume 3 Number 1 Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas Citation C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas. Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science. 2007 Volume 3 Number 1. Abstract The aim of this review was to describe child abuse cases in ancient Greek mythology. Names like Hercules, Saturn, Aesculapius, Medea are very familiar. The stories can be divided into 3 categories: child abuse from gods to gods, from gods to humans and from humans to humans. In these stories children were abused in different ways and the reasons were of social, financial, political, religious, medical and sexual origin. The interpretations of the myths differed and the conclusions seemed controversial. Archaeologists, historians, and philosophers still try to bring these ancient stories into light in connection with the archaeological findings. The possibility for a dentist to face a child abuse case in the dental office nowadays proved the fact that child abuse was not only a phenomenon of the past but also a reality of the present. INTRODUCTION courses are easily available to everyone. Child abuse may be defined as any non-accidental trauma, On 1860 the forensic odontologist Ambroise Tardieu, neglect, failure to meet basic needs or abuse inflicted upon a referring to 32 cases, made a connection between subdural child by a caretaker that is beyond the acceptable norm of haematoma and abuse. In 1874 a church group in New York childcare in our culture. Abused children found in all 1 City took a child named Mary-Helen from home in which economic, social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and she was being abused. -

How Disney's Hercules Fails to Go the Distance

Article Balancing Gender and Power: How Disney’s Hercules Fails to Go the Distance Cassandra Primo Departments of Business and Sociology, McDaniel College, Westminster, MD 21157, USA; [email protected] Received: 26 September 2018; Accepted: 14 November; Published: 16 November 2018 Abstract: Disney’s Hercules (1997) includes multiple examples of gender tropes throughout the film that provide a hodgepodge of portrayals of traditional conceptions of masculinity and femininity. Hercules’ phenomenal strength and idealized masculine body, coupled with his decision to relinquish power at the end of the film, may have resulted in a character lacking resonance because of a hybridization of stereotypically male and female traits. The film pivots from hypermasculinity to a noncohesive male identity that valorizes the traditionally-feminine trait of selflessness. This incongruous mixture of traits that comprise masculinity and femininity conflicts with stereotypical gender traits that characterize most Disney princes and princesses. As a result of the mixed messages pertaining to gender, Hercules does not appear to have spurred more progressive portrayals of masculinity in subsequent Disney movies, showing the complexity underlying gender stereotypes. Keywords: gender stereotypes; sexuality; heroism; hypermasculinity; selflessness; Hercules; Zeus; Megara 1. Introduction Disney’s influence in children’s entertainment has resulted in the scrutiny of gender stereotypes in its films (Do Rozario 2004; Dundes et al. 2018; England et al. 2011; Giroux and Pollock 2010). Disney’s Hercules (1997), however, has been largely overlooked in academic literature exploring the evolution of gender portrayals by the media giant. The animated film is a modernization of the classic myth in which the eponymous hero is a physically intimidating protagonist that epitomizes manhood. -

Melquart and Heracles: a Study of Ancient Gods and Their Influence

Studia Antiqua Volume 2 Number 2 Article 12 February 2003 Melquart and Heracles: A Study of Ancient Gods and Their Influence Robin Jensen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Classics Commons, and the History Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Jensen, Robin. "Melquart and Heracles: A Study of Ancient Gods and Their Influence." Studia Antiqua 2, no. 2 (2003). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol2/iss2/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. On the left, in one of the earliest surviving depictions of Heracles, c. 620 b.c., he is shown slaying the evil Geryon and his guard dog. He wears the usual Greek hero’s kilt with geometric patterns and bronze greaves like his opponent. Over them, he wears the impervious skin of the Nemean lion, his first labor. His knapsack is probably a bowcase. On the right, a basalt bas-relief of Melkart, c. 800 b.c., was found at Breidj near Aleppo. He wears the distinctive Phoenecian kilt and carries a pierced bronze battle-ax. His conical headress links him to Assyrian depictions of the gods. The Aramaic inscription invokes Melkart, “Protector of the city.” Melquart and Heracles: A Study of Ancient Gods and Their Influence Robin Jensen Societies in general revere their heroes, holding them in high regard and giving them adulation—sometimes deserved, sometimes not. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA.