Tools for School Staff Working with Students with Emotional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paycheck Protection Program Loans

Paycheck Protection Program Loans Loan Amount Business Name Headquarters City a $5-10 million ABO LEASING CORPORATION PLYMOUTH a $5-10 million ACMS GROUP INC CROWN POINT a $5-10 million ALBANESE CONFECTIONERY GROUP, INC. MERRILLVILLE a $5-10 million AMERICAN LICORICE COMPANY LA PORTE a $5-10 million AMERICAN STRUCTUREPOINT, INC. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million ASH BROKERAGE, LLC FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million ASHLEY INDUSTRIAL MOLDING, INC. ASHLEY a $5-10 million BEST CHAIRS INCORPARATED FERDINAND a $5-10 million BIOANALYTICAL SYSTEMS, INC. WEST LAFAYETTE a $5-10 million BLUE & CO LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million BLUE HORSESHOE SOLUTIONS INC. CARMEL a $5-10 million BRAVOTAMPA, LLC MISHAWAKA a $5-10 million BRC RUBBER & PLASTICS INC FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million BTD MANUFACTURING INC BATESVILLE a $5-10 million BUCKINGHAM MANAGEMENT, L.L.C. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million BYRIDER SALES OF INDIANA S LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million C.A. ADVANCED INC WAKARUSA a $5-10 million CFA INC. BATESVILLE a $5-10 million CINTEMP INC. BATESVILLE a $5-10 million CONSOLIDATED FABRICATION AND CONSTRUCTORS INC GARY a $5-10 million COUNTRYMARK REFINING & LOGISTICS LLC MOUNT VERNON a $5-10 million CROWN CORR, INC. GARY a $5-10 million CUNNINGHAM RESTAURANT GROUP LLC INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million DECATUR COUNTY MEMORIAL HOSPITAL GREENSBURG a $5-10 million DIVERSE STAFFING SERVICES, INC. INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million DRAPER, INC. SPICELAND a $5-10 million DUCHARME, MCMILLEN & ASSOCIATES, INC. FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million ELECTRIC PLUS, INC AVON a $5-10 million ENVIGO RMS, LLC INDIANAPOLIS a $5-10 million ENVISTA, LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million FLANDERS ELECTRIC MOTOR SERVICE INC EVANSVILLE a $5-10 million FOX CONTRACTORS CORP FORT WAYNE a $5-10 million FUSION ALLIANCE, LLC CARMEL a $5-10 million G.W. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 10, 2012 to Sun. September 16, 2012 Monday September 10, 2012

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 10, 2012 to Sun. September 16, 2012 Monday September 10, 2012 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Nothing But Trailers IMAX - Grand Canyon Adventure - River at Risk Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So HDNet presents a half hour of Noth- Narrated by Academy Award®-winning filmmaker, actor, and noted environmentalist Robert ing But Trailers. See the best trailers, old and new in HDNet’s collection. Redford. Follow the great Colorado River as it reveals the most pressing environmental story of our time - the world’s growing shortage of fresh water. 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Hustle 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT Mickey and the team are thrust into a daring daylight heist to retrieve stolen diamonds that Hustle are hidden beneath a police station and wanted back by the owner. Mickey and the team are thrust into a daring daylight heist to retrieve stolen diamonds that are hidden beneath a police station and wanted back by the owner. 6:00 PM ET / 3:00 PM PT JAG 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Fighting Words - While respected and decorated Marine General Earl Watson has been as- Honky Tonk TV: Your Country signed to lead the joint task force charged with capturing all the remaining high-value targets This week we’ve got Lee Brice and Colt Ford. Our girl Roxy chats with JT Hodges and he in Iraq, a troubling revelation surfaces. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

2020 Spring Newsletter

Volume 20, Issue 1 Winter 2020 From the Executive Director How do you measure a year? This question has been asked – sung, even – from scientists to philosophers, since the beginning of time. If you look to highlights surrounding a year’s end, any news source will provide a plethora of statistics and key names along with events and trends of each year, decade, century, or – for those around during Y2k – the millennia! If you pose this question to the characters from the Broadway hit, Rent, they’ll tell you measuring a year is about more than 525,600 minutes… that it’s about seasons of love. Markers in time cause us to pause, to reflect on the past and prepare ourselves for new beginnings. Perhaps one of our most challenging questions at the Center for Loss and Bereavement is – how do we measure our mission’s impact each year? In supporting those in the throes of grief, we know the passage of time is measured by the intricate, unique, and complicated ways that people are able to find restoration over each new year of milestones. It’s about gaining new meaning or purpose in life through loss’s twists and turns, and about maintaining connections with those living and lost – for some – with life, itself. Each year, in our assessment of impact, we tune in to the many stories shared in the trusted spaces of our therapy offices and peer groups. We hope to see that within our roles, we’ve been able to support the grief experience of our clients in ways that help them to find comfort, understanding, and growth through their journey. -

Military Trivia Toll Free Numbers for Contacting VA 1

Military Trivia Toll Free Numbers for Contacting VA 1. In the military legal television series "JAG," lawyer Harmon "Harm" Rabb is a member of what service? A) Army Department Name(s) Toll Free Number(s) B) Navy Benefits (VA): C) Air force Burial D) Marines Death Pension 2. What 1980’s sitcom star played the role of Lt. Bob Anderson in the short-lived WWII flying drama Baa Baa Black- sheep? Dependency Indemnity Compensation A) Alan Thicke Direct Deposit B) John Goodman Directions to VA Benefits Regional Offices C) Ted Danson Disability Compensation D) John Larroquette Disability Pension 3. The cast of the television series “Combat!”, which ran from 1962-67, trained at what California army base to prepare Education for the show? A) Fort Irwin Home Loan Guaranty B) Fort Ord Medical Care C) Fort Buchanan Vocational Rehabilitation and Employment…………………..1-800-827-1000 D) Fort Drum Beneficiaries in receipt of Pension Benefits………………….. 1-877-294-6380 Last Month’s Trivia Answers: CHAMPVA Meds by Mail ………………………………….1-888-385-0235 (or)1-866-229-7389 1. Virginia Combat Call Center………………………………………...1-877-WAR-VETS (1-877-927-8387) 2. Arkansas Debt Management Center (Collection of Non-Medical Debts)...1-800-827-0648 3. Ohio Children of Women Vietnam Veterans (CWVV) Foreign Medical Program (FMP) Spina Bifida Health Care Program…………………………….1-877-345-8179 (or)1-888-820-1756 Civilian Health and Medical Program of the Department of Veterans Affairs (CHAMPVA) The military recognizes that military medals are often a cherished part of family history and makes replacement medals, decora- CHAMPVA In-House Treatment Initiative (CITI)……………..1-800-733-8387 tions, and awards available to veterans or their next of kin if the veteran is no longer living or able to make the request on his or eBenefits Technical Support………………………………….1-800-983-0937 her own behalf. -

Gangs and Organized Crime Groups

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE JOURNAL OF FEDERAL LAW AND PRACTICE Volume 68 November 2020 Number 5 Acting Director Corey F. Ellis Editor-in-Chief Christian A. Fisanick Managing Editor E. Addison Gantt Associate Editors Gurbani Saini Philip Schneider Law Clerks Joshua Garlick Mary Harriet Moore United States The Department of Justice Journal of Department of Justice Federal Law and Practice is published by Executive Office for the Executive Office for United States United States Attorneys Attorneys Washington, DC 20530 Office of Legal Education Contributors’ opinions and 1620 Pendleton Street statements should not be Columbia, SC 29201 considered an endorsement by Cite as: EOUSA for any policy, 68 DOJ J. FED. L. & PRAC., no. 5, 2020. program, or service. Internet Address: The Department of Justice Journal https://www.justice.gov/usao/resources/ of Federal Law and Practice is journal-of-federal-law-and-practice published pursuant to 28 C.F.R. § 0.22(b). Page Intentionally Left Blank Gangs & Organized Crime In This Issue Introduction....................................................................................... 1 David Jaffe Are You Maximizing Ledgers and Other Business Records in Drug and Organized Crime Investigations? ............. 3 Melissa Corradetti Jail and Prison Communications in Gang Investigations ......... 9 Scott Hull Federally Prosecuting Juvenile Gang Members........................ 15 David Jaffe & Darcie McElwee Scams-R-Us Prosecuting West African Fraud: Challenges and Solutions ................................................................................... 31 Annette Williams, Conor Mulroe, & Peter Roman Gathering Gang Evidence Overseas ............................................ 47 Christopher J. Smith, Anthony Aminoff, & Kelly Pearson Exploiting Social Media in Gang Cases ....................................... 67 Mysti Degani A Guide to Using Cooperators in Criminal Cases...................... 81 Katy Risinger & Tim Storino Novel Legal Issues in Gang Prosecutions .................................. -

U.S. Government Publishing Office Style Manual

Style Manual An official guide to the form and style of Federal Government publishing | 2016 Keeping America Informed | OFFICIAL | DIGITAL | SECURE [email protected] Production and Distribution Notes This publication was typeset electronically using Helvetica and Minion Pro typefaces. It was printed using vegetable oil-based ink on recycled paper containing 30% post consumer waste. The GPO Style Manual will be distributed to libraries in the Federal Depository Library Program. To find a depository library near you, please go to the Federal depository library directory at http://catalog.gpo.gov/fdlpdir/public.jsp. The electronic text of this publication is available for public use free of charge at https://www.govinfo.gov/gpo-style-manual. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: United States. Government Publishing Office, author. Title: Style manual : an official guide to the form and style of federal government publications / U.S. Government Publishing Office. Other titles: Official guide to the form and style of federal government publications | Also known as: GPO style manual Description: 2016; official U.S. Government edition. | Washington, DC : U.S. Government Publishing Office, 2016. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016055634| ISBN 9780160936029 (cloth) | ISBN 0160936020 (cloth) | ISBN 9780160936012 (paper) | ISBN 0160936012 (paper) Subjects: LCSH: Printing—United States—Style manuals. | Printing, Public—United States—Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Publishers and publishing—United States—Handbooks, manuals, etc. | Authorship—Style manuals. | Editing—Handbooks, manuals, etc. Classification: LCC Z253 .U58 2016 | DDC 808/.02—dc23 | SUDOC GP 1.23/4:ST 9/2016 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055634 Use of ISBN Prefix This is the official U.S. -

A Suggested Professional Reading Program for Judge Advocates

260 MILITARY LAW REVIEW [Vol. 204 READ ANY GOOD (PROFESSIONAL) BOOKS LATELY?: A SUGGESTED PROFESSIONAL READING PROGRAM FOR JUDGE ADVOCATES LIEUTENANT COLONEL JEFF BOVARNICK ∗ I challenge all leaders to make a focused, personal commitment to read, reflect, and learn about our profession and our world. Through the exercise of our minds, our Army will grow 1 stronger. ∗ Judge Advocate, U.S. Army. Presently assigned as Professor and Chair International & Operational Law Department, The Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center & School (TJAGLCS), U.S. Army, Charlottesville, Virginia. LL.M., 2002, TJAGLCS, Charlottesville, Virginia; J.D., 1992, New England School of Law; B.B.A., 1988, University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Previous assignments include: Chief, Investigative Judge Team, Law and Order Task Force, Forward Operating Base Shield, Baghdad, Iraq, 2008–2009; Deputy Staff Judge Advocate, 1st Infantry Division, Fort Riley, Kansas, 2006–2008; Student, Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, 2005–2006; Chief, Military Justice, 82d Airborne Division, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, 2003–2005; Chief, Operational Law, XVIII Airborne Corps, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and Combined Joint Task Force 180, Bagram, Afghanistan, 2002–2003; Student, 50th Graduate Course, 2001–2002; Chief, Criminal Law Division & Chief, Client Services Division, Fort Sam Houston, Texas, 1999–2001; Observer/Controller, Joint Readiness Training Center, Fort Polk, Louisiana, 1998; Defense Counsel, Fort Bragg Field Office, U.S. Army Trial Defense Service, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, 1996–1997; Trial Counsel and Chief, Operational Law, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky, 1993–1996; Member of the bars of Massachusetts, the Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, and the Supreme Court of the United States. -

Desertification

SPM3 Desertification Coordinating Lead Authors: Alisher Mirzabaev (Germany/Uzbekistan), Jianguo Wu (China) Lead Authors: Jason Evans (Australia), Felipe García-Oliva (Mexico), Ismail Abdel Galil Hussein (Egypt), Muhammad Mohsin Iqbal (Pakistan), Joyce Kimutai (Kenya), Tony Knowles (South Africa), Francisco Meza (Chile), Dalila Nedjraoui (Algeria), Fasil Tena (Ethiopia), Murat Türkeş (Turkey), Ranses José Vázquez (Cuba), Mark Weltz (The United States of America) Contributing Authors: Mansour Almazroui (Saudi Arabia), Hamda Aloui (Tunisia), Hesham El-Askary (Egypt), Abdul Rasul Awan (Pakistan), Céline Bellard (France), Arden Burrell (Australia), Stefan van der Esch (The Netherlands), Robyn Hetem (South Africa), Kathleen Hermans (Germany), Margot Hurlbert (Canada), Jagdish Krishnaswamy (India), Zaneta Kubik (Poland), German Kust (The Russian Federation), Eike Lüdeling (Germany), Johan Meijer (The Netherlands), Ali Mohammed (Egypt), Katerina Michaelides (Cyprus/United Kingdom), Lindsay Stringer (United Kingdom), Stefan Martin Strohmeier (Austria), Grace Villamor (The Philippines) Review Editors: Mariam Akhtar-Schuster (Germany), Fatima Driouech (Morocco), Mahesh Sankaran (India) Chapter Scientists: Chuck Chuan Ng (Malaysia), Helen Berga Paulos (Ethiopia) This chapter should be cited as: Mirzabaev, A., J. Wu, J. Evans, F. García-Oliva, I.A.G. Hussein, M.H. Iqbal, J. Kimutai, T. Knowles, F. Meza, D. Nedjraoui, F. Tena, M. Türkeş, R.J. Vázquez, M. Weltz, 2019: Desertification. In:Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, E. Calvo Buendia, V. Masson-Delmotte, H.-O. Pörtner, D.C. Roberts, P. Zhai, R. Slade, S. Connors, R. van Diemen, M. Ferrat, E. Haughey, S. Luz, S. -

HISTORY of the COMSTOCK PATENT MEDICINE BUSINESS and Dr

••v v. ..;•• HISTORY of the COMSTOCK PATENT MEDICINE BUSINESS and Dr. Morse's Indian Root Pills by Robert B. Shaw MAY 2 61972 / HJDIKQW *n SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS City of Washington 1972 SERIAL PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION The emphasis upon publications as a means of diffusing knowledge was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. In his formal plan for the Insti tution, Joseph Henry articulated a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This keynote of basic research has been adhered to over the years in the issuance of thousands of titles in serial publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Annals of Flight Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the research and collections of its several museums and offices and of professional colleagues at other institutions of learning. These papers report newly acquired facts, synoptic interpretations of data, or original theory in specialized fields. These pub lications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, laboratories, and other interested institutions and specialists throughout the world. Individual copies may be obtained from the Smithsonian Institution Press as long as stocks are available. -

Community Health Assessment

HARFORD COUNTY HEALTH DEPARTMENT DECEMBER 14, 2012 COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT Acknowledgements Harford County Health Department was the lead organization in the preparation of this report: Susan Kelly, Health Officer, Russell Moy, MD, Deputy Health Officer, Joan Salim, Laura McIntosh and Bari Klein, Health Policy Analysts, contributed to the preparation of this document. Minor revisions made February 19, 2014 Harford County Health Department Community Health Assessment Page 1 Index I. Executive Summary C. Obesity D. Summary II. Introduction VII. Access to Health Care III. Health Assessments and A. Health Insurance Coverage Planning Initiatives B. Availability of Preventive A. Healthy Harford Health Services B. County Health Rankings C. Access to Medical and C. State and Local Health Dental Care Improvement Process D. Access to Healthy Food D. Obesity Task Force E. Summary E. Summary VIII. Public Health Resources IV. Demographic and Economic Profile IX. Conclusion A. Location and Population B. Age X. Appendix C. Diversity A. Maps D. Education B. Local Health Improvement E. Income Coalition (LHIC) Survey F. Housing and Transportation Summary2011-2012 G. Poverty C. 2011-2012 Harford County H. Special Populations Resource Guide I. Summary V. Health Outcomes A. Births and Infant Deaths B. Mortality (Chronic Disease) C. Mortality (other causes) D. Summary VI. Health Behaviors A. Tobacco Use B. Alcohol and Substance Abuse Harford County Health Department Community Health Assessment Page 2 I. Executive Summary The Harford County Health Department’s Community Health Assessment (CHA) is an opportunity to learn about the health status of our community. It is a collaborative process that describes the health status of the population, identifies areas for health improvement, determines factors that contribute to health issues, and identifies resources that can be mobilized to improve the population’s health. -

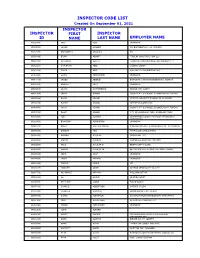

INSPECTOR CODE LIST Created on September 01, 2021 INSPECTOR INSPECTOR FIRST INSPECTOR ID NAME LAST NAME EMPLOYER NAME 000234700 0000 0000 UNKNOWN

INSPECTOR CODE LIST Created On September 01, 2021 INSPECTOR INSPECTOR FIRST INSPECTOR ID NAME LAST NAME EMPLOYER NAME 000234700 0000 0000 UNKNOWN 000390900 JAMES AAMODT GSI ENGINEERING, LLC: WICHITA 000578700 MOHAMMED ABAAULA KTI 000521900 BRAM ABBOTT TRIDENT CONSTRUCTION, LLC 000482900 NATHANIEL ABEITA TRANSYSTEMS CORPORATION: KANSAS CITY 000622041 CHRISTIAN ABEL LIBERAL-CONST 000503800 TYLER ABELL KAW VALLEY ENGINEERING INC 000189400 GARIC ABENDROTH UNKNOWN 000141400 JAMES ABERLE BARTLETT & WEST ENGINEERS INC: TOPEKA 000355600 RONALD ABLA UNKNOWN 000630030 LAURA ACHTERBERG DODGE CITY-CONST 000313600 JIMMY ADAMS COOK FLATT & STROBEL ENGINEERS PA: TOPEKA 000345600 DAVID ADAMS CRETEX CONCRETE PRODUCTS: SHAWNEE 000383100 BUTCH ADAMS MILES EXCAVATING INC 000464700 James ADAMS COOK FLATT & STROBEL ENGINEERS PA: TOPEKA 000507900 DOUG ADAMS CITY OF OVERLAND PARK: OVERLAND PARK 000304300 JON ADAMYK MCPHERSON COUNTY HIGHWAY DEPARTMENT: MCPHERSON 000249600 BRANDON ADDINGTON UNKNOWN 000485200 KOFFI ADELA-KLOUTSE KIRKHAM MICHAEL & ASSOCIATES INC: ELLSWORTH 000380600 ERNEST ADU TERRACON CONSULTANTS 000342500 RAMIRO AGUILAR SMOKY HILL LLC 000487400 OSCAR AGUILAR CORNEJO & SONS INC: WICHITA 000292200 TACO AGUILAR IV EMERY SAPP & SONS 000458400 PEDRO AGUILAR JR BETTIS ASPHALT & CONSTRUCTION: TOPEKA 000258200 JOHN AGUT UNKNOWN 000384300 JESSE AHRENS UNKNOWN 000291500 TADELE AKALU KTI 000460200 TIMOTHY AKINS OLSSON ASSOCIATES: OLATHE 000175700 MUHAMMET AKPINAR KSU_MANHATTAN 000160129 ALI AL INIZI OLATHE-CONST 000340600 MATTHEW ALBER KLEINFELDER 000577300