ABCD Resource Kit Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020

Electronic Gaming Machines Strategy 2015-2020 Version: 1.1 Date approved: 22 December 2015 Reviewed: 15 January 2019 Responsible Department: Planning Related policies: Nil 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................. 3 2 Definitions ............................................................................................................. 3 3 Acronyms .............................................................................................................. 5 4 Scope .................................................................................................................... 5 5 Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 5 6 Gambling and EGMs in the City of Casey ........................................................... 6 7 City of Casey Position on Electronic Gaming Machines ................................... 7 7.1 Advocacy & Partnerships ....................................................................................... 7 7.2 Local Economy ....................................................................................................... 8 7.3 Consultation & Information Provision ...................................................................... 9 7.4 Community Wellbeing ............................................................................................ 9 7.5 Planning Assessment .......................................................................................... -

Submission to the Standing Committee on Transport and Regional Services

Submission to the Standing Committee on Transport and Regional Services May 2005 Version 1 SEATS Submission to the Standing Committee on Transport and Regional Services EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Councils of Gippsland, Gippsland Area Consultative Committee (GACC), and South East Australian Transport Strategy Inc (SEATS) are delighted to provide this submission to the Inquiry into the Integration of Regional Rail and Road Freight Transport and their Interface with Ports. Gippsland is located in eastern Victoria and extends from the Great Dividing Range in the north, through rich and productive timber and agricultural grazing land, to the Bass Strait coastline in the south and from the New South Wales border in the east to the Latrobe Region and Phillip Island in the west and south-west. The Region comprises the LGAs of Bass Coast, East Gippsland, Latrobe, South Gippsland, Wellington and Baw Baw Shire The Region covers an area of almost 40,000 sq kms, or 17.5% of the total area of Victoria. The major urban centres are Bairnsdale, Leongatha, Moe, Morwell, Sale, Traralgon, Warragul and Wonthaggi. Gippsland’s major industries include dairy, timber and forest products, energy production, other agriculture, cement and sand extraction, and tourism. These industries are described below. Figure 2 provides an overview of the transport network in the Gippsland Region. The region is serviced by road, rail, air and sea infrastructure. FIGURE 1 GIPPSLAND REGION MAJOR TRANSPORT INFRASTRUCTURE Submission to the Standing Committee on Transport and Regional Services Key Issues Raised in this Submission A. Land Transport Access to Ports A.1. Rail Gauge Incompatibility The long term retention of broad gauge is a significant problem for the region of Gippsland and the competitiveness of its economy. -

Engaging Young People in Regional Centres

Engaging young people in regional centres A discussion paper by the Youth Affairs Council of Victoria and the Victorian Rural Youth Services initiative April 2013 The Youth Affairs Council of Victoria The Youth Affairs Council of Victoria (YACVic) is a vibrant, member based organisa- tion that represents and advocates for young people and the organisations that work with them. YACVic has worked for and with young Victorians and the services that support them for over 50 years. Our vision is for a Victorian community in which all young people are valued as active participants, have their rights recognised and are treated fairly and with respect. The Victorian Rural Youth Services The Victorian Rural Youth Services (VRYS) initiative sets out to advance research, training and policy development to support the rural youth sector. It aims to promote the strengths of young people in rural communities, and address the disadvantag- es these young people can face. The initiative is supported by the VRYS network, a network of services concerned with young people’s wellbeing in rural Victoria, and it operates through the Youth Affairs Council of Victoria. The Youth Affairs Council of Victoria Inc Level 2, 180 Flinders St, Melbourne VIC 3000 Ph: (03) 9267 3799 Fax: (03) 9639 1622 www.yacvic.org.au Joanna Hatcher, Rural Youth Services Support and Advocacy Officer [email protected] April 2013 Contents Background ....................................................................................................................................... -

City of Latrobe 2010

Early Childhood Community Profile City of Latrobe 2010 Early Childhood Community Profile City of Latrobe 2010 This Early Childhood community profile was prepared by the Office for Children and Portfolio Coordination, in the Victorian Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. The series of Early Childhood community profiles draw on data on outcomes for children compiled through the Victorian Child and Adolescent Monitoring System (VCAMS). The profiles are intended to provide local level information on the health, wellbeing, learning, safety and development of young children. They are published to: • Equip communties with the information required to identify the needs of children and families within their local government area. • Aid Best Start partnerships with local service development, innovation and program planning to improve outcomes for young children. • Support local government and regional planning of early childhood services; and • Assist community service agencies working with vulnerable families and young people. The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Human Services, the Department of Health and the Australian Bureau of Statistics provided data for this document. Early Childhood Community Profiles i Published by the Victorian Government Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. September 2010 © Copyright State of Victoria, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may -

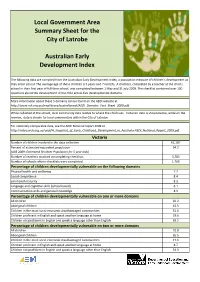

Local Government Area Summary Sheet for the City of Latrobe

Local Government Area Summary Sheet for the City of Latrobe Australian Early Development Index The following data are compiled from the Australian Early Development Index, a population measure of children’s development as they enter school. The average age of these children is 5 years and 7 months. A checklist, completed by a teacher at the child’s school in their first year of full-time school, was completed between 1 May and 31 July 2009. The checklist contained over 100 questions about the development of the child across five developmental domains. More information about these 5 domains can be found on the AEDI website at http://www.rch.org.au/emplibrary/australianedi/AEDI_Domains_Fact_Sheet_2009.pdf While collected at the school, local community data relates to where the child lives. Victorian data is shown below, while on the reverse, data is shown for local communities within the City of Latrobe. For nationally comparable data, see the AEDI National report 2009 at http://video.wch.org.au/aedi/A_Snapshot_of_Early_Childhood_Development_in_Australia-AEDI_National_Report_2009.pdf Victoria Number of children involved in the data collection 61,187 Percent of estimated equivalent population 94.2 (ABS 2009: Estimated Resident Population for 5 year olds) Number of teachers involved in completing checklists 3,783 Number of schools where checklists were completed 1,765 Percentage of children developmentally vulnerable on the following domains Physical health and wellbeing 7.7 Social competence 8.4 Emotional maturity 8.3 Language and cognitive -

The VPA Working in Latrobe Valley PROGRESS REPORT & EVALUATION

The VPA working in Latrobe Valley PROGRESS REPORT & EVALUATION MARCH 2020 Your partner in planning great places for a growing Victoria © VICTORIAN PLANNING AUTHORITY 2020 The VPA working In Latrobe Valley Progress Report & Evaluation was developed by the VPA on behalf of the Victorian Government. Any projections are based on reasonable assumptions at the time of publication but should not be relied upon without first seeking appropriate expert advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure that the information in this document is factually correct at the time of publication, the VPA does not warrant the accuracy, completeness or relevance of the information. Any person using or relying upon this document does so on the basis that the State of Victoria shall bear no responsibility or liability whatsoever for any errors, faults, defects or omissions in the information. Table of contents 1 Background 4 1.1 Purpose & introduction 4 1.2 The VPA’s role 4 1.3 The Latrobe Valley 5 1.4 Funding channels 6 2 Focus of VPA support 8 2.1 Unlocking land supply 8 2.2 Supporting planning priorities initiated by councils 9 2.3 Developing strategies to address complex planning problems 10 2.4 Facilitating issue resolution for strategic sites 11 2.5 Building stakeholder capacity 12 3 NEXT STEPS 13 3.1 What we have learned 13 3.2 What we will do next 14 Figures Figure 1 Future directions for settlement, prepared from Gippsland Regional Growth Plan, 2014, Victorian Government 6 Figure 2 West Sale Industrial Area 9 Figure 3 Issue resolution process proposed -

Victoria Government Gazette No

Victoria Government Gazette No. S 257 Wednesday 14 December 2005 By Authority. Victorian Government Printer Country Fire Authority Act 1958 the south-eastern angle of Allotment 133 in that DECLARATION OF parish; thence westerly by a road to the south- FIRE DANGER PERIOD western angle of that allotment; thence southerly by a road to the southern boundary of the parish; In pursuance of the powers conferred by thence westerly by that boundary to the north- Section 4 of the Country Fire Authority Act western angle of the Parish of Gatum Gatum; 1958, I, Neil G. Bibby, Chief Executive Officer thence southerly by the western boundary of the of the Country Fire Authority, after consultation parish to the south-western angle of Allotment with the Secretary to the Department of 5, Section 1; thence south-easterly by a road to Sustainability and Environment, hereby declare the northern angle of Allotment 14, Section 3; the following periods to be the Fire Danger thence south-westerly by the western boundaries Period in the municipal districts of the of Allotments 14 and 16 and a line to the municipalities or parts of municipalities western boundary of the parish; thence southerly specified, commencing on the dates shown and, by that boundary and a line to the north-western unless varied by subsequent declaration, ending angle of Allotment 4, Section 1, Parish of at 0100 hours on 1 May 2006. Toolang; thence further southerly by the western To commence from 0100 hours on boundary of that allotment to a point in line with 19 December 2005: the southern -

Reform of the Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services Program

Mental Health Community Support Services June 2014 Fact Sheet 2: Information for Existing Clients Fact Sheet: Information for Existing Clients This fact sheet provides information for current clients of mental health community support services provided under the Victorian Psychiatric Disability Rehabilitation and Support Services (PDRSS) program. It includes information about the changes that will happen to these services over the next few months, when these changes will occur and how the changes might affect you. As part of these changes the Victorian Government will also change the name of the PDRSS program to Mental Health Community Support Services (MHCSS) program from August 2014. This change is about supporting you. The changes will ensure access to mental health community support services is fair and equitable by ensuring people most disabled by their mental health condition do not miss out on the support they need. The reforms will make it easier for new and returning consumers and carers to get help no matter where they live. This will be achieved by establishing a centralised intake point for all referrals in each local area. A fact sheet explaining how the new intake assessment system will work will be made available shortly. We also know you want services to be of a consistent quality and designed around your individual needs and preferences. This is why we are introducing Individualised Client Support Packages. They will replace standard, moderate and intensive Home Based Outreach Services, Day Programs, Care Coordination, Aged Intensive Program and Special Client Packages from 1 August 2014. Your support package will help you to develop the life skills needed to live well in the community and to manage your mental illness. -

Various Planning Schemes Combined 3 May 2021

Form 1 Section 38(1) NOTICE OF APPROVAL OF AMENDMENT TO A PLANNING SCHEME TO BE PRESENTED TO PARLIAMENT On 29 April 2021 the Minister approved Amendment C378melb to the Melbourne Planning Scheme. The amendment was prepared by Minister for Planning. The Melbourne City Council will be responsible for administering the scheme. The amendment applies the Environmental Significance Overlay - Schedule 2 to protect trees identified as significant in the Exceptional Tree Register 2019 on an interim basis until 27 April 2023. The Minister exempted the Minister from the requirements of section 17, 18 and 19 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987 being the requirement to: Give a copy of the amendment, together with the explanatory report and any document applied, adopted or incorporated in the amendment to the relevant municipal council. Make the amendment available for inspection until the amendment is approved. Give notice of the amendment to every Minister, public authority and municipal council that the planning authority believes may be materially affected by the amendment Give notice of the amendment to the owners and occupiers of land that the planning authority believes may be materially affected by the amendment. Give notice of the amendment to any Minister, public authority, municipal council or person prescribed. Publish a notice of the amendment in a newspaper generally circulating in the area. Publish a notice of the preparation of the amendment in the Government Gazette. The Minister exempted Minister for Planning from the requirements 6 and 7 of the Planning and Environment Regulations 2015 being the requirement for the purposes of giving notice of an amendment in accordance with section 19 of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. -

Shifting Focus: Alternative Pathways for Communities and Economies

Shifting focus: alternative pathways for communities and economies A resource kit produced by Latrobe City and Monash University SHIFTING FOCUS: ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS FOR COMMUNITIES AND ECONOMIES A RESOURCE KIT An outcome of the Community Partnering project funded by: ¨ Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs (Australian Research Council) ¨ Latrobe City ¨ Monash University With support from: ¨ Australian Paper ¨ Loy Yang Power SHIFTING FOCUS: ALTERNATIVE PATHWAYS FOR COMMUNITIES AND ECONOMIES A RESOURCE KIT Jenny Cameron and Katherine Gibson University of Newcastle and University of Western Sydney Latrobe City and Monash University Traralgon and Melbourne, Victoria 2001 Copyright © Latrobe City and Monash University 2001 This resource kit is copyright. It may be used and reproduced for non-commercial activities only. Use for any other purpose must be by prior written permission of Latrobe City and Monash University. Requests and inquiries should be addressed to: Community Development and Planning Unit, Latrobe City, PO Box 345, Traralgon, VIC, 3844, Australia. Published by Latrobe City and Monash University Traralgon and Melbourne, Victoria. ISBN 0 9578620 0 8 Desktop Publishing: Jillian Dickinson Cover Design: Liz Butler The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily represent the views of Latrobe City or Monash University. FOREWORD The Community Partnering process detailed in this Resource Kit involves working hand-in- hand with people who have been marginalised, and assisting them to build community- based projects. The kit includes documented examples of how positives can be found in negative situations, in this case, the restructuring of the power industry. The ideas found in this document will assist communities to establish microeconomic communities in their local area using people as their major resource. -

Factsheet: Alcohol and Other Drug Treatment in Victoria April 2015

Factsheet: Alcohol and other drug treatment in Victoria April 2015 Information for health and human service providers This factsheet provides information about the current alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment system in Victoria, including catchments, treatment streams, intake and assessment, and referral pathways. Overview A number of changes to AOD treatment services were introduced in 2014 in order to improve outcomes for vulnerable Victorians. Twenty-seven community organisations now lead the delivery of adult non-residential treatment and support services across 16 catchment areas in the state, with a total of 83 providers participating, most through consortia arrangements. In addition, residential, youth and Aboriginal services continue to be available. Catchments Adult non-residential AOD treatment services are now delivered within 16 catchments across the state. There are seven catchments in rural and regional Victoria (see figure 1) and nine catchments in metropolitan Melbourne (see figure 2). Figure 1: Rural and regional catchments Figure 2: Metropolitan catchments Catchments were established to improve collaboration, planning and service coordination between AOD services and other health and welfare services, and to reduce system fragmentation. Approved service provider/s in each catchment work collaboratively under a common plan that identifies critical service gaps and development needs at the local level. Catchments are not intended to restrict client choice and it is expected that some clients may choose to access services -

Issues and Opportunities Paper June 2020

Issues and Opportunities Paper June 2020 Acknowledgements Basketball Victoria acknowledges the support of the Victorian Government in this planning project through the Participation Initiative Grants Program. We also acknowledge the staff at Latrobe City Council, Basketball Associations, members and supporters for providing background information and support for this planning project. Introduction Latrobe City Energy is the identified pathway program for basketball in Gippsland. The program has gone through various iterations over the past 30 years. In recent times the program has experienced a variety of challenges which have raised concerns regarding the sustainability of the current program as a means of providing an elite pathway for basketball in Gippsland. Across Latrobe City Council, Baw Baw Shire Council and Wellington Shire Council there are 12 Basketball Victoria Country affiliated basketball associations, with approximately 7,000 registered weekly participants. With the $20 million investment by the Victorian State Government and Latrobe City Council into the redevelopment of the Traralgon Sports Stadium, and further support from the Victorian Government for the establishment of that Stadium to host one of seven high performance basketball hubs around the State, it is critical that a sustainable and successful pathway program be established for Gippsland basketball. Additionally, Latrobe Valley has also been successful in attracting the NBL Blitz in 2017, hosting the Triple Crown event in 2018 between the Melbourne Boomers and Bendigo Spirit, as well as numerous other community and basketball programs. Never in the region’s history has such significant resources been provided for the sport, creating such a unique opportunity for basketball participants who deserve a sustainable pathway to participate at the elite level.