Assumptions and Implementation of the Policy of Polish Government in the Field of the Development of Shipbuilding Industry in Po

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pdf Esp 862.Pdf

SZCZECIN 2016 European Capital of Culture Candidate Text Dana Jesswein-Wójcik, Robert Jurszo, Wojciech Kłosowski, Józef Szkandera, Marek Sztark English translation Andrzej Wojtasik Proof-reading Krzysztof Gajda Design and layout Rafał Kosakowski www.reya-d.com Cover Andrej Waldegg www.andrejwaldegg.com Photography Cezary Aszkiełowicz, Konrad Królikowski, Wojciech Kłosowski, Andrzej Łazowski, Artur Magdziarz, Łukasz Malinowski, Tomasz Seidler, Cezary Skórka, Timm Stütz, Tadeusz Szklarski Published by SZCZECIN 2016 www.szczecin2016.pl ISBN 978-83-930528-3-7 (Polish edition) ISBN 978-83-930528-4-4 (English edition) This work is licensed under a Creative Commons licence (Attribution – Noncommercial – NoDerivs) 2.5 Poland I edition Szczecin 2010 Printed by KADRUK s.c. www.kadruk.com.pl SZCZECIN 2016 European Capital of Culture Candidate We wish to thank all those who contributed in different ways to Szczecin’s bid for the title of the European Capital of Culture 2016. The group is made up of experts, consultants, artists, NGO activists, public servants and other conscious supporters of this great project. Our special thanks go to the following people: Marta Adamaszek, Krzysztof Adamski, Patrick Alfers, Katarzyna Ireneusz Grynfelder, Andreas Guskos, Elżbieta Gutowska, Amon, Wioletta Anders, Maria Andrzejewska, Adrianna Małgorzata Gwiazdowska, Elke Haferburg, Wolfgang Hahn, Chris Andrzejczyk, Kinga Krystyna Aniśko, Paweł Antosik, Renata Arent, Hamer, Kazu Hanada Blumfeld, Martin Hanf, Drago Hari, Mariusz Anna Augustynowicz, Rafał Bajena, Ewa -

DESIGN for SAFETY: an Integrated Approach to Safe European Ro-Ro Ferry Design

PUBLIC FINAL REPORT DESIGN FOR SAFETY: An Integrated Approach to Safe European Ro-Ro Ferry Design SAFER EURORO (ERB BRRT-CT97-5015) SU-01.03 Page 1 PUBLIC FINAL REPORT CONTRACT N°: ERB BRRT-CT97-5015 ACRONYM: SAFER EURORO TITLE: DESIGN FOR SAFETY: AN INTEGRATED APPROACH TO SAFE EUROPEAN RORO FERRY DESIGN THEMATIC NETWORK CO-ORDINATOR: University of Strathclyde, Ship Stability Research Centre (SU) TN ACTIVITIES CO-ORDINATORS: European Association of Universities in Marine Technology (WEGEMT) Germanischer Lloyd (GL) WS Atkins (WSA) Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research (TNO) Maritime Research Institute Netherlands (MARIN) SIREHNA Registro Italiano Navale (RINA) Det Norske Veritas (DNV) National Technical University of Athens (NTUA) TN START DATE: 01/10/97 DURATION: 48 MONTHS DATE OF ISSUE OF THIS REPORT: JANUARY 2003 Thematic Network funded by the European Community under the Industrial and Materials Technologies (BRITE-EURAM III) Programme (1994-1998) Thematic Network DESIGN FOR SAFETY, Public Final Report SAFER EURORO (ERB BRRT-CT97-5015) SU-01.03 Page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1. OBJECTIVES OF THE THEMATIC NETWORK 7 2. BACKGROUND 10 2.1 Background 11 2.2 Research Focus 11 2.3 Structure of the Report 12 2.3.1 Risk-Based Design Framework 12 2.3.2 Evaluation Criteria 13 2.3.3 Principal Hazard Categories – Risk-Based Design Tools 13 2.3.4 Risk-Based Design Methodology 14 3. RISK-BASED DESIGN FRAMEWORK 15 [Professor Dracos Vassalos & Dr Dimitris Konovessis, SU-SSRC] 3.1 State of the Art 16 3.1.1 Background 16 3.1.2 Safety-Related Drivers for Change 16 3.1.3 Approaches to Ship Safety 17 3.1.4 On-going and Planned Research 18 3.2 Approach Adopted 18 3.3 The Safety Assurance Process 19 3.4 References 20 4. -

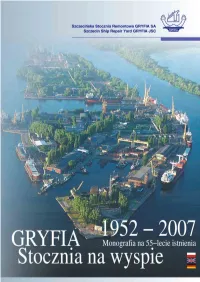

Gryfia Monog 2007

1952 – 2007 The monography for 55th Anniversary Die Monographie für 55 Jahre der Tätigkeit GRYFIA The shipyard on an island Werft auf der Insel GRYFIA GRYFIA the shipyard on an island die Reparaturwerft auf einem Insel Szczecin Ship Repair Yard GRYFIA JSC celebrates Die Reparaturwerft GRYFIA AG in Szczecin begeht in dem this year its 55th anniversary. Since 1952, it worked with laufenden Geschäftsjahr ihr 55-jähriges Betriebsjubiläum. Seit 1952 ist considerable effects in service for the polish marine econ- diese Werft im Dienste der polnischen Seewirtschaft tätig und hat bis omy, and the achievements and results of this 55-year heute bedeutsame Erfolge erzielt. Die innerhalb der letzten 55 Jahre long work, in spite of the whirl of history, remained erzielten Ergebnisse und Errungenschaften sind trotz der unquestionable. geschichtlichen Verwirrungen und Entwicklungen unbestritten, den sie Throughout all the years of its existence, the shipyard zeugen von den Leistungen der Werftarbeiter und Schiffbauer. raised its reputation by enriching fixed assets, technologi- Die Werft hat in der Vergangenheit ihre Marktposition von Jahr zum Jahr verbessert, indem sie ihr Anlagevermögen, ihr technologisches Potential cal potential and increasing the staff qualifications, and erweitert sowie die Qualität der Produktion systematisch verbessert hat. the quality of work. Szczecin repair yard became famous In diesem Zeitraum wurde die Arbeitsqualität im wesentlichen dadurch in Poland and abroad, as the solid and responsible con- verbessert, daß die berufliche Qualifikationen der Belegschaft kon- tractor, able to cope with the most difficult technical chal- tinuierlich erhöht wurde. Die Stettiner Werft ist im In- und Ausland als lenges in the area of repair, building or rebuilding of solider, verantwortungsbewußter Partner bekannt, der die schwierigsten ships. -

Shipbuilding and Ship Repair Sectors in Poland, Estonia, Czech Republic

Jonschera 4/10, 91-849 Łódź, Poland, tel/fax (+48 42) 656 4978, www.nobe.pl This report was prepared by NOBE for the ENTERPRISE DG Unit A3 of the European Commission in the framework of contract n° PRS/98/501703 (or PSE/99/502333). 2 Table of contents.............................................................................................................3 List of tables ....................................................................................................................4 List of graphs...................................................................................................................5 Sources ...........................................................................................................................6 Abbreviations...................................................................................................................6 1. Executive summary.........................................................................................................7 1.1 Macroeconomic overview..........................................................................................7 1.2 General characteristics of the industry ......................................................................8 1.3 Effects of EU accession ..........................................................................................11 1.4 Present and future competitive advantage – views of the industry ........................11 1.5 Conclusions: ability to withstand competitive pressure ...........................................15 -

Shipbreaking Bulletin of Information and Analysis on Ship Demolition # 45, from July 1 to September 30, 2016

Shipbreaking Bulletin of information and analysis on ship demolition # 45, from July 1 to September 30, 2016 November 2, 2016 Content One that will never reach Alang 1 Livestock carrier 13 Car carrier 57 Ships which are more than ships 4 Ferry/passenger ship 14 Cable layer, dredger 58 Offshore platforms: offshoring at all costs 5 General cargo 17 Offshore: drilling ship, crane ship, 59 Who will succeed in breaking up Sino 6, 6 Container ship 23 offshore service vessel, tug and when? Reefer 36 The END: Modern Express, 63 Accidents: Gadani; Captain Tsarev 7 Tanker 38 wrecked, salvaged, scrapped Should all container ships be demolished? 9 Chemical tanker 42 and suspected smuggler Overview July-August-September 2016 10 Gas tanker 44 Sources 66 Factory ship 12 Bulk carrier 46 One that will never reach Alang The true product of a Merchant Navy that is too mercantile to be humane. A Liberia-flagged freighter formerly flying the flags of China and Panama, a de facto Greek ship-owner with an ISM (International Safety Management) nowhere to be found whose single ship officially belongs to Fin Maritime Inc, a virtual company registered on a paradise island, a broken up Taiwanese and Filipino crew, the ex- Benita, stateless slave sailing the Pacific Ocean, North Seas, Indian Ocean, South Seas, and the Atlantic Ocean, detained in Australia and the United States of America, with approximately a hundred deficiencies reported in worldwide ports, with a varnished good repute from a distinguished classification society, had everything to be where she is : 4,400 meters deep, 94 nautical miles off Mauritius. -

Maritime Security How It Affects Your Business

January 2003 AND ENGINEERING NEWS \ * l§||2— Eg zj**.. r- " ' Many new ships to come Maritime Security How it affects your business Investment in Design: New Gas Turbines Technology • New Shtp Contracts • Marine Electronics • SatCom E-Mail Data Voice all in one... and one solution for all SATELLITE GSM One service provider for voice & data One optimized platform to launch all your software applications One space-saving integrated hardware component One consolidated easy-to-read bill One reliable connection One e-mail address on land or at sea One Website for your crew to manage their own accounts One low price • One solution • One Company Wave SeaWave Communicator 3.0 with MAX SeaWeat her* One Source for reliable Weather Newport, Rhode Island • (800)746-6251 • Fax: (401)846-9012 • E-mail: [email protected] • www.seawave.com Circle 254 on Reader Service Card or visit www.maritimereporterinfo.com Ur>c,c? i i 4s r, & f: Alone, but never adrift. Look to the leader. Look to Sea Tel. Circle 252 on Reader Service Card or visit vvww.maritimereporterinfo.com K> Your ships are half a world away in nasty conditions. Relax. You can depend on Sea Tel for reliable, uninterrupted satellite k communications at sea. No other company has the depth and breadth of products from TV-at-Sea to mega bandwidth communications. No other company has the technology that allows you to monitor your Sea Tel from halfway around the world. No other company even comes close for worldwide service and support. For more than two decades, twenty thousand plus large system installations prove Sea Tel is the one both navies and commercial fleets trust. -

Pats Baltexpo 2005.Pdf

2 September 2005 Editorial Significant Ships According to well-informed sources, at the end of 2004 the number of ships of the com- mercial fleet worldwide amounted to 89 960 SHIPBUILDING totaling 633,3 million CGT. The average age of BALTEXPO - SPECIAL ISSUE ships came to 22 years. At the same time, the September 2005 world order book reached another all-time re- cord of more than 90 million CGT. In 2004, shi- pyards worldwide delivered 1729 vessels, amo- PUBLISHER unting to 25,5 million CGT, more than three qu- Shipbuilding and Shipping Ltd. Na Ostrowiu 1 Street arters of which were produced by Asian ship- 80-958 Gdañsk, Poland builders. On the other hand, European yards www.okretownictwo.pl recorded the strongest increase in new orders ACCOUNT: ING Bank from 4 million CGT in 2003 to 6,8 million CGT PL 1050 1764 1000 0018 0203 7869 in 2004. In the same year Polish yards had new orders for 51 ships totaling 1 088 744 CGT, Chairman Editor-in-Chief: 34 of which were container ships. Grzegorz Landowski Phone +48 58 307 12 49 In 2004, the Polish yards delivered 25 ships [email protected] of 448 684 CGT and the value of 754,7 million Subscription USD. Two of them were really significant. The Polish yards in 2004 and 2005, as well as some and advertisement: Aleksandra Dylejko RINA list of Significant Ships of the Year 2004 ships that are currently being under construc- Phone +48 58 307 15 54 mentioned the arctic container carrier Mary tion. -

September 2006

September 2006 CONTENTS: www.naszemorze.com.pl Order books of Polish yards .......................................................... 4 Polish shipbuilding industry overwiev ....................................... 7 First LNG carrier to be built in Poland ........................................... 8 Worlds largest stainless steel parcel tankers ............................... 9 Heavy deck cargo in ice .............................................................. 11 Largest container carriers from Szczecin Shipyard so far .......... 14 Standard ships and the most successful .................................. 16 The 8234 type - pretty big and really fast .................................... 17 Kota Perkasa box carrier 2681 TEU ........................................... 18 The largest floating garages ..................................................... 20 Modern ro-ro feeder .................................................................... 22 Innovative con-ro vessel from Szczecin ...................................... 24 SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT Car and passenger ferries Argyle and Bute ............................... 27 Shipbuilding l Machinery & Marine Big double-ended ferry Bast III .................................................. 30 Technology International Trade Faire ø Hamburg Germany Double-ended car-passenger ferry Folkestadt ........................... 32 26-29 September 2006 Good looking shuttle ................................................................... 33 Second Trinity House vessel launched in Gdansk .................... -

Ships Made in Germany 2018 Ships Made in Germany

Ships 2018 in co-operation with Verband für Schiffbau Made in Germany und Meerestechnik e. V. Supplement February 2019 Ships made in Germany Contents German shipbuilding industry continues on course 5 New challenges in a difficult environment 6 Shipyard cooperation trend continues 10 Deliveries & contracts of German shipyards in 2018 ������������15 »AIDAnova« – Innovation made in Germany 28 »Years of research led to success« 32 »Ship of the year award 2018« for Meyer Werft 33 Setting out for new horizons 34 Peters Werft plans further investments 36 »Room for manoeuvering within EU regulation« ��������������������� 38 Fire boat sets new benchmarks 40 Blohm+Voss all set for the future 42 An old lady rejuvenated ���������������������������������������������������� 44 Online shops going maritime 46 2 HANSA International Maritime Journal – Supplement Ships made in Germany 2018 Ships made in Germany Supplement to Index of Advertisers HANSA International Maritime Journal Andritz Hydro GmbH ����������������������19 February 2019 DGzRS 23 Chief Editor: Krischan Förster HeroLang ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 21 Deputy Chief Editor: Michael Meyer Internationales Editors: Felix Selzer | Thomas Wägener Maritimes Museum Hamburg 21 Schiffahrts-Verlag »Hansa« GmbH & Co KG -

Download a FREE SAMPLE

MARITIME REPORTER r i AND ENGINEERING NEWS I www.marinelink.«om >2 i. Coatings & Corrosion Control Product's • Government Update • Ferliship's Ship Contracts • Repair Report MPH1 These companies support the best oil spill response program in the US. 0bp ChevronTexaco ConocoPhillips E^onMobi GIRNT INDUSTRIES, INC. MOTIVA MURPHY ENTERPRISES LLC Shell Si Saudi Aramco Working Together OIL CORPORATION PORTLAND PIPE LINE CORPORATION o TESORO What about yours? They're members of the And MSRC would respond Either way, we want to have you Marine Preservation Association immediately. on board. (MPA). As such, they not only The point is, as responsible Contact us at 480-991-5500 support the largest, dedicated, corporate citizens, these or visit our Website at cost effective, standby oil spill companies and others are doing mmv.mpaz.org response program in the United their parts to minimize damage States, they have direct and from oil spills. In fact, they've immediate access to it, as well. been doing it as MPA members That program is called for over a decade. the Marine Spill Response So what about your company? Marine Preservation Association Corporation or MSRC. If you'd like to see your Funder of Should a significant oil spill company's logo in this ad, ever affect an MPA member call us today to receive a new company, their first and most membership packet. Or visit MSRC& urgent call would be to MSRC. our website. Marine Spill Response Corporation Circle 245 on Reader Service Card For almost a decade iotun Paints has been at quality production standards.