Muslim Marseille: the Metropolization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

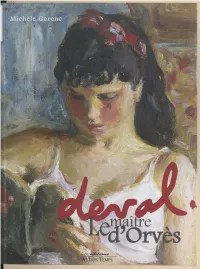

Deval. Le Maître D'orvès

Cet ouvrage est publié à l'occasion du centenaire de la naissance du peintre Pierre Deval (1897-1993), avec le concours : du conseil général du Var des amis de la vieille Valette et des sites de la galerie Michel Estades. La galerie Michel Estades présente en permanence des oeuvres de Deval. 18 rue Henri Seillon,, 83 000 Toulon Tél. 04 94 89 49 98 Malassis n 51 142 rue des Rosiers, 93400 Saint-Ouen Tél. 01 40 Il 32 60 - 1 CbMver/Hn* "La lecture à Orvès" - détail huile sur toile collection galerie Michel Estadcs Michèle Gorenc LedfBNès f� Temps Regard AUTRES TEMPS Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Conseil général du Var, des Amis de La Vieille Valette et des sites, de la Galerie Michel Estades. (Ç) Editions Autres Temps - 1997 Tous droits de traduction, adaptation et reproduction interdits ppur tous pays. à Philippe, Anne, Pierre, Jeanne, à Françoise, Oliver, Colin, Anthony, Kenneth, cet hommage à leur père et grand-père, pour le centième anniversaire de sa naissance. Remerciements Cette biographie a vu le jour grâce à l'appui de nombreuses personnes qui en ont facilité les recherches. D'abord Pierre Deval qui m'a fait partager ses souvenirs et a mis ses archives à ma disposition, Ses enfants, Philippe et Françoise, pour leur amical soutien, Alain Bitossi, président des Amis de La Vieille Valette et des Sites pour son aide constante et ses conseils avisés, Mmes Chemain et Dauphiné, MM. Chemain, Daspre et Dauphiné, professeurs des universités, pour leurs encouragements, MM. Bréon et Chanel, conservateurs des musées, pour leur solidarité, Mme Bronia Clair pour ses documents, Mme Prévot, bibliothécaire du Fonds Doucet, pour son accueil, Mme Chaney et ses enfants pour leur gentillesse et la qualité de leurs souvenirs, ainsi que tous les collectionneurs qui, dans l'anonymat, portent un amour commun à l'œuvre du maître d'Orvès. -

Our Base Ajaccio (Base Is Open Only in Season (April – October) Port Tino Rossi Quai De La Citadelle 20000 AJACCIO GPS Position : 41°55,21'N - 08°44,57'E

Our base Ajaccio (base is open only in season (April – October) Port Tino Rossi Quai de la Citadelle 20000 AJACCIO GPS position : 41°55,21'N - 08°44,57'E Base Manager : Pascal Narran + 33 (0) 7 60 21 00 20 Customer service [email protected] + 33 (0) 4 95 21.89.21 Service commercial Port Tino Rossi 20 000 Ajaccio Tel : +33 (0)4 95 21 89 21 - Fax : +33 (0)4 85 21 89 25 Thanks to call upon arrival or to go directly to Soleil Rouge Yachting Member of Dream Yacht Charter office Opening hours From 09:00am to 06:00pm (18h00) ACCESS BY FERRY BOAT Port of Ajaccio From Marseille with SNCM www.sncm.fr or La Méridionale www.lameridionale.fr From Toulon with Corsica Ferries www.corsica-ferries.fr From Nice with SNCM www.sncm.fr or Corsica Ferries www.corsica-ferries.fr ACCESS BY PLANE Ajaccio Airport (14 km – 15 minutes) Flights from Paris and/or other French cities with www.aircorsica.com, www.xlairways.fr et www.airfrance.com Flights from Brussels with www.jetairfly.com Flights from Lyon with www.regional.com Flights from Amsterdam with www.transavia.com Service commercial Port Tino Rossi 20 000 Ajaccio Tel : +33 (0)4 95 21 89 21 - Fax : +33 (0)4 85 21 89 25 TRANSFERS BUS Line 8: Airport > Bus station Timetables and rates : http://www.bus-tca.fr/index.php?langue=FR + 33 (0) 4 95 23 29 41 TAXI We can organize your transfers CAR RENTAL Europcar - 16 cours Grandval : + 33 (0) 4 95 21 05 49 Hertz - 8 cours Grandval : + 33 (0) 4 95 21 70 94 Avis - 1 rue Paul Colonna d’Istria : + 33 ( 0) 4 95 23 92 55 CAR PARK Parking « Margonajo » close to the ferry boat (41°55'35.94"N 8°44'22.19"E). -

Grand Mosque of Paris a Story of How Muslims Rescued Jews During the Holocaust Written and Illustrated by Karen Gray Ruelle and Deborah Durland Desaix

Holiday House Educators’ Guide An ALA Notable Children’s Book An Orbis Pictus Award Recommended Title “This . seldom-told piece of history . will expand . interfaith relations.”—The Bulletin Themes • Anti-Semitism/Bigotry • Courage • Fear • Survival • Danger • Hope Grades 3 up HC: 978-0-8234-2159-6 • $17.95 PB:978-0-8234-2304-0 • $8.95 The Grand Mosque of Paris A Story of How Muslims Rescued Jews During the Holocaust written and illustrated by Karen Gray Ruelle and Deborah Durland DeSaix About the Book The Grand Mosque of Paris proved to be an ideal temporary hiding place for escaped World War II prisoners and for Jews of all ages, including children. Paris had once been a safe haven for Jews who were trying to escape Nazi-occupied Germany, but in 1940 everything changed. The Nazis overtook the streets of Paris, and the city was no longer safe for Jews. Many Parisians were too terrified themselves to try and help their Jewish friends. Yet during that perilous time, many Jews found refuge in an unlikely place: the sprawling complex of the Grand Mosque of Paris. Behind its walls, the frightened Jews found an entire community, with gardens, apartments, a clinic, and a library. But even the mosque was under the watchful eyes of the Nazis, so it wasn’t safe for displaced Jews to remain there very long. Karen Gray Ruelle and Deborah Durland DeSaix tell the almost unknown story of this resistance and the people of the Grand Mosque and how their courage, faith, and devotion to justice saved the lives of so many. -

Murder in Aubagne: Lynching, Law, and Justice During the French

This page intentionally left blank Murder in Aubagne Lynching, Law, and Justice during the French Revolution This is a study of factions, lynching, murder, terror, and counterterror during the French Revolution. It examines factionalism in small towns like Aubagne near Marseille, and how this produced the murders and prison massacres of 1795–1798. Another major theme is the conver- gence of lynching from below with official terror from above. Although the Terror may have been designed to solve a national emergency in the spring of 1793, in southern France it permitted one faction to con- tinue a struggle against its enemies, a struggle that had begun earlier over local issues like taxation and governance. This study uses the tech- niques of microhistory to tell the story of the small town of Aubagne. It then extends the scope to places nearby like Marseille, Arles, and Aix-en-Provence. Along the way, it illuminates familiar topics like the activity of clubs and revolutionary tribunals and then explores largely unexamined areas like lynching, the sociology of factions, the emer- gence of theories of violent fraternal democracy, and the nature of the White Terror. D. M. G. Sutherland received his M.A. from the University of Sussex and his Ph.D. from the University of London. He is currently professor of history at the University of Maryland, College Park. He is the author of The Chouans: The Social Origins of Popular Counterrevolution in Upper Brittany, 1770–1796 (1982), France, 1789–1815: Revolution and Counterrevolution (1985), and The French Revolution, 1770– 1815: The Quest for a Civic Order (2003) as well as numerous scholarly articles. -

Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2018 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2018 Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Caleb Joseph Cumberland Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018 Part of the African History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, and the Legal History Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Cumberland, Caleb Joseph, "Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa" (2018). Senior Projects Spring 2018. 249. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2018/249 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Colonial Control and Power through the Law: Territoriality, Sovereignty, and Violence in German South-West Africa Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Caleb Joseph Cumberland Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2018 Acknowledgments I would like to extend my gratitude to my senior project advisor, Professor Drew Thompson, as without his guidance I would not have been able to complete such a project. -

MARSEILLE MARSEILLE 2018 MARSEILLE Torsdag 4/10

MARSEILLE MARSEILLE 2018 MARSEILLE Torsdag 4/10 4 5 6 Transfer till Arlanda Flyg 7 Fredag 5/10 Lördag 6/10 Söndag 7/10 8 9 10 Med guide: Picasso museum Med guide: 11 Les Docks Libres i Antibes Euromediterranée Quartiers Libres Förmiddag 12 Lunch @ Les illes du Micocoulier Transfer till 13 Nice Lunch @ Lunch på egen hand Flyg 14 Transfer till La Friche Belle de Mai Arlanda Express Marseille 15 Egen tid Med guide: Vårt förslag: Yes we camp! 16 La Cité Radieuse FRAC, Les Docks, Le Silo Parc Foresta Le Corbusier Smartseille 17 La Marseillaise Etermiddag CMA CGM Tillträde till MUCEM 18 Transfer till hotellet (Ai Weiwei) Check-in Egen tid 19 20 Middag @ La Mercerie 21 Middag @ Middag @ Sepia La Piscine Kväll 22 23 Since Marseille-Provence was chosen to be the European Capital of Culture in 2013, the Mediterranean harbour city has become a very atracive desinaion on the architectural map of the world. Besides new spectacular cultural buildings along the seashore, the city has already for a long ime been in a comprehensive process of urban transformaion due to Euroméditerranée, the large urban development project. Under the inluence of the large-scale urban development project of the city, the Vieux Port (Old Harbour) was redesigned 2013 by Norman Foster and several new cultural buildings were realised: amongst others the MuCEM – Museum for European and Mediterranean Civilisaions (Arch. Rudy Riccioi), the Villa Méditerranée (Arch. Stefano Boeri) as well as the FRAC – Regional Collecion of contemporary Art (Arch. Kengo Kuma), which today are regarded as lagship projects of the city. -

Some Non-Human Languages of Thought

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2019 Some Non-Human Languages of Thought Nicolas J. Porot The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3396 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOME NON-HUMAN LANGUAGES OF THOUGHT by NICOLAS POROT A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 NICOLAS POROT All Rights Reserved ii Some Non-Human Languages of Thought by Nicolas Porot This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in [program]in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Some Non-Human Languages of Thought by Nicolas Porot Advisor: Eric Mandelbaum This dissertation asks: What might we learn if we take seriously the possibility that some non-human animals possess languages of thought (LoTs)? It looks at the ways in which this strategy can help us better understand the cognition and behavior of several non-human species. In doing so, it offers support, from disparate pieces of the phylogenetic tree, for an abductive argument for the presence of LoTs. Chapter One introduces this project. -

Marseille, France

MARSEILLE, FRANCE Wind of Change on the Old Port Hotel Market Snapshot February 2016 H O T E L S 1 Hotel C2 (Source: © Hotel) Marseille, France Hotel Market Snapshot, February 2016 HIGHLIGHTS Marseille, the political, cultural and economic centre of the MARSEILLE - Key facts & Figures (2015) Bouches-du-Rhône department and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte Population (inner city) 852 500 (2012) d'Azur region, is France’s second largest city. Surface (inner city) 240.6 km² Unemployment 18.4% (2012) The city’s tourism industry has experienced a turning point in Tourism arrivals 1.2 million 2013 when Marseille held the title of European Capital of Overnight stays 2.1 million Culture. In preparation of this major event, the city has initiated numerous rejuvenation and redevelopment projects in order to % Leisure tourism 46.0% replace its often battered reputation in the media with the % Business tourism 54.0% image of an innovative and enjoyable city. Since then, the city % Domestic overnights 75.0% has tried to capitalise on this event to further develop its % International overnights 25.0% popularity as a tourist destination. Number of hotels 82 Number of hotel rooms 5 769 This edition of our hotel market snapshot will thus take a closer Source: BNP Paribas Real Estate Hotels, Tourism Observatory look into Marseille’s tourism and hotel industry and will Marseille, INSEE present the city’s forthcoming hotel openings. WHAT’S NEW? WHAT’S COMING UP IN MARSEILLE? With the aim of providing a more lively area for pedestrians and hosting temporary exhibitions and events, the Old Port (‘Vieux Port’) is currently being modernised. -

The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870

The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Dzanic, Dzavid. 2016. The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33840734 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 A dissertation presented by Dzavid Dzanic to The Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts August 2016 © 2016 - Dzavid Dzanic All rights reserved. Advisor: David Armitage Author: Dzavid Dzanic The Civilizing Sea: The Ideological Origins of the French Mediterranean Empire, 1789-1870 Abstract This dissertation examines the religious, diplomatic, legal, and intellectual history of French imperialism in Italy, Egypt, and Algeria between the 1789 French Revolution and the beginning of the French Third Republic in 1870. In examining the wider logic of French imperial expansion around the Mediterranean, this dissertation bridges the Revolutionary, Napoleonic, Restoration (1815-30), July Monarchy (1830-48), Second Republic (1848-52), and Second Empire (1852-70) periods. Moreover, this study represents the first comprehensive study of interactions between imperial officers and local actors around the Mediterranean. -

Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species

MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. Payne Museum of Zoology The University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Ann Arbor MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN May 26, 1982 MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN The publications of the Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan, consist of two series-the Occasional Papers and the Miscellaneous Publications. Both series were founded by Dr. Bryant Walker, Mr. Bradshaw H. Swales, and Dr. W. W. Newcomb. The Occasional Papers, publication of which was begun in 1913, serve as a medium for original studies based principally upon the collections in the Museum. They are issued separately. When a sufficient number of pages has been printed to make a volume, a title page, table of contents, and an index are supplied to libraries and individuals on the mailing list for the series. The Miscellaneous Publications, which include papers on field and museum techniques, monographic studies, and other contributions not within the scope of the Occasional Papers, are published separately. It is not intended that they be grouped into volumes. Each number has a title page and, when necessary, a table of contents. A complete list of publications on Birds, Fishes, Insects, Mammals, Mollusks, and Reptiles and Amphibians is available. Address inquiries to the Director, Museum of Zoology, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATIONS MUSEUM OF ZOOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN NO. 162 Species Limits in the Indigobirds (Ploceidae, Vidua) of West Africa: Mouth Mimicry, Song Mimicry, and Description of New Species Robert B. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

A University of Sussex Phd Thesis Available Online Via Sussex

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details The German colonial settler press in Africa, 1898-1916: a web of identities, spaces and infrastructure. Corinna Schäfer Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Sussex September 2017 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: Summary As the first comprehensive work on the German colonial settler newspapers in Africa between 1898 and 1916, this research project explores the development of the settler press, its networks and infrastructure, its contribution to the construction of identities, as well as to the imagination and creation of colonial space. Special attention is given to the newspapers’ relation to Africans, to other imperial powers, and to the German homeland. The research contributes to the understanding of the history of the colonisers and their societies of origin, as well as to the history of the places and people colonised.