The Collected Works of William Morris Volume 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'William Morris

B .-e~ -. : P R I C E T E N CENTS THE NEW ORDER SERIES: NUMBER ONE ‘William Morris CRAFTSMAN, WRITER AND SOCIAL RBFORM~R BP OSCAR LOVELL T :R I G G S PUBLISHED BY THE OSCAR L. TRIGGS PUBLISHING COMPANY, S58 DEARBORN STREET, CHICAGO, ILL. TRADE SUPPLIED BY THE WESTERN NRWS COMIPANY, CHICAGO TEN TEN LARGE VOLUMES The LARGE VOLUMES Library dl University Research RELIGION, PHILOSOPHY SOCIOLOGY, SCIENCE HISTORY IN ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS The Ideas That Have Influenced Civilization IN THE ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS Translated and Arranged in Chronological or Historical Order, so that Eoglish Students may read at First Hand for Themselves OLIVER J. THATCHER, Ph. D. Dcparfmmt of Hisfory, University of Chicago, Editor in Chid Assisted by mme than 125 University Yen, Specialists in their own fields AN OPINION I have purchased and examined the Documents of the ORIGINAL RESEARCH LIBRARY edited by Dr. Thatcher and am at once impressed with the work as an ex- ceedingly valuable publication, unique in kind and comprehensive in scope. ./ It must prove an acquisition to any library. ‘THOMAS JONATHAN BURRILL. Ph.D., LL.D., V&e-Pres. of the University of NZinois. This compilation is uniquely valuable for the accessi- bility it gives to the sources of knowledge through the use of these widely gathered, concisely stated, con- veniently arranged, handsomely printed and illustrated, and thoroughly indexed Documents. GRAHAM TAYLOR, LL.D., Director of The Institute of Social Science at fhe Universify of Chicago. SEND POST CARD FOR TABLE OF CONTENTS UNIVERSITY RESEARCH EXTENSION AUDITORIUM BUILDING, CHICAGO TRIGGS MAGAZINE A MAGAZIiVE OF THE NEW ORDER IN STATE, FAMILY AND SCHOOL Editor, _ OSCAR LOVELL TRIGGS Associates MABEL MACCOY IRWIN LEON ELBERT LANDONE ‘rHIS Magazine was founded to represent the New Spirit in literature, education and social reform. -

The Harmony of Structure: the Earthly Paradise

CHAPTER I THE HARMONY OF STRUCTURE: THE EARTHLY PARADISE In the following analysis of The Earthly Paradise I shall try to show first what was Morris's purpose throughout the composition of the work, and secondly, what was his actual achievement, with its significance for English poetry. In bringing together in The Earthly Paradise stories and legends from various cultures and various periods, Morris did not set out to point the contrast between the classical, the medieval and the saga methods, which could have been done only by a strict preservation or reproduction of the methods of each type. He aimed rather at showing the contribution of each tradition to the common literary fund of Western Europe — especially of English literary tradition — as it crystallised towards the end of the Middle Ages, in the time of Chaucer, as he says explicitly himself, if not indeed — as internal evidence may perhaps lead us to conclude — during the century of Caxton and Malory, just after Chaucer's death. In the light of more discriminate modem examination of the Middle Ages, we may incline to think that the atmosphere which Morris evokes in The Earthly Paradise is that of the very end of the Middle Ages, just before Renaissance classicism was to make familiar a different, more scholarly attitude towards classical tra dition, and to render less easy the acceptance of popular traditional forms and methods (cf. infra pp. 26-7). Morris was thus deliberately returning to the historical moment at which he considered the national cultural tradition had last existed in a pure form unspoilt by the "pride of pedantry"9 which he judged guilty of divorcing culture from the mass of the nation. -

Proceedings 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction iv Beacon 2012 Sponsors v Conference Program vi Outstanding Papers by Panel 1 SESSION I POLITICAL SCIENCE 2 Alison Conrad “Negative Political Advertising and the American Electorate” Mentor: Prof. Elaine Torda Orange County Community College EDUCATION 10 Michele Granitz “Non-Traditional Women of a Local Community College” Mentor: Dr. Bahar Diken Reading Area Community College INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES 18 Brogan Murphy “The Missing Link in the Puzzling Autism Epidemic: The Effect of the Internet on the Social Impact Equation” Mentor: Prof. Shweta Sen Montgomery College HISTORY 31 Megan G. Willmes “The People’s History vs. Company Profit: Mine Wars in West Virginia, the Battle of Blair Mountain, and the Ongoing Fight for Historical Preservation” Mentor: Dr. Joyce Brotton Northern Virginia Community College COMMUNICATIONS I: POPULAR CULTURE 37 Cristiana Lombardo “Parent-Child Relationships in the Wicked Child Sub-Genre of Horror Movies” Mentor: Dr. Mira Sakrajda Westchester Community College ALLIED HEALTH AND NURSING 46 Ana Sicilia “Alpha 1 Anti-Trypsin Deficiency Lung Disease Awareness and Latest Treatments” Mentor: Dr. Amy Ceconi Bergen Community College i TABLE OF CONTENTS (CONTINUED) SESSION II PSYCHOLOGY 50 Stacy Beaty “The Effect of Education and Stress Reduction Programs on Feelings of Control and Positive Lifestyle Changes in Cancer Patients and Survivors” Mentor: Dr. Gina Turner and Dr. Sharon Lee-Bond Northampton Community College THE ARTS 60 Angelica Klein “The Art of Remembering: War Memorials Past and Present” Mentor: Prof. Robert Bunkin Borough of Manhattan Community College NATURAL AND PHYSICAL SCIENCES 76 Fiorella Villar “Characterization of the Tissue Distribution of the Three Splicing Variants of LAMP-2” Mentor: Prof. -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Italian Renaissance: Envisioning Aesthetic Beauty and the Past Through Images of Women

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN Carolyn Porter Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/113 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Carolyn Elizabeth Porter 2010 All Rights Reserved “DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI AND THE ITALIAN RENAISSANCE: ENVISIONING AESTHETIC BEAUTY AND THE PAST THROUGH IMAGES OF WOMEN” A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Virginia Commonwealth University. by CAROLYN ELIZABETH PORTER Master of Arts, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2007 Bachelor of Arts, Furman University, 2004 Director: ERIC GARBERSON ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF ART HISTORY Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia August 2010 Acknowledgements I owe a huge debt of gratitude to many individuals and institutions that have helped this project along for many years. Without their generous support in the form of financial assistance, sound professional advice, and unyielding personal encouragement, completing my research would not have been possible. I have been fortunate to receive funding to undertake the years of work necessary for this project. Much of my assistance has come from Virginia Commonwealth University. I am thankful for several assistantships and travel funding from the Department of Art History, a travel grant from the School of the Arts, a Doctoral Assistantship from the School of Graduate Studies, and a Dissertation Writing Assistantship from the university. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

The Use of the Arthurian Legend by the Pre-Raphaelites

University of Colorado, Boulder CU Scholar University Libraries Digitized Theses 189x-20xx University Libraries Summer 6-1-1905 The seU of the Arthurian Legend Matilda Krebs University of Colorado Boulder Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.colorado.edu/print_theses Recommended Citation Krebs, Matilda, "The sU e of the Arthurian Legend" (1905). University Libraries Digitized Theses 189x-20xx. 2. http://scholar.colorado.edu/print_theses/2 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by University Libraries at CU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Libraries Digitized Theses 189x-20xx by an authorized administrator of CU Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University Archives THE USE OF THE ARTHURIAN LEGEND BY THE PRE-RAPHAELITES A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF COLORADO BY MATILDA KREBS A Candidate for the Degree of Master of Arts BOULDER, COLORADO JUNE, 1905 PREFACE. The following pages are the result of many happy hours spent in the library, in an earnest endeavor to become better acquainted with Truth and Beauty. The author does not pose as a critic for she has little knowledge of literary art either theoretical or practical, and none of pic- torial. Should this self-imposed task prove to be of even the slightest benefit to other students, the pleasure to the writer would be multiplied many fold. M ATILDA KREBS. OUTLINE OF THESIS. I. The Arthuriad. 1. The origin of the Arthuriad. 2. Development of the Arthuriad. 3. Use of the Arthuriad by early writers. 4. Revival of interest in the Arthuriad through Rossetti's “ King Arthur's Tomb.” II. -

Pre-Raphaelites and the Book

Pre-Raphaelites and the Book February 17 – August 4, 2013 National Gallery of Art Pre-Raphaelites and the Book Many artists of the Pre-Raphaelite circle were deeply engaged with integrating word and image throughout their lives. John Everett Millais and Edward Burne-Jones were sought-after illustrators, while Dante Gabriel Rossetti devoted himself to poetry and the visual arts in equal measure. Intensely attuned to the visual and the liter- ary, William Morris became a highly regarded poet and, in the last decade of his life, founded the Kelmscott Press to print books “with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty.” He designed all aspects of the books — from typefaces and ornamental elements to layouts, where he often incorporated wood- engraved illustrations contributed by Burne-Jones. The works on display here are drawn from the National Gallery of Art Library and from the Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library. front cover: William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910), proof print of illustration for “The Lady of Shalott” in Alfred Tennyson, Poems, London: Edward Moxon, 1857, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (9) back cover: Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828 – 1882), proof print of illustration for “The Palace of Art” in Alfred Tennyson, Poems, London: Edward Moxon, 1857, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (10) inside front cover: John Everett Millais, proof print of illustration for “Irene” in Cornhill Magazine, 1862, wood engraving, Mark Samuels Lasner Collection, on loan to the University of Delaware Library (11) Origins of Pre-Raphaelitism 1 Carlo Lasinio (1759 – 1838), Pitture a Fresco del Campo Santo di Pisa, Florence: Presso Molini, Landi e Compagno, 1812, National Gallery of Art Library, A.W. -

Autumn Leaves

Autumn Leaves EBC e-catalogue 31 2020 George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK 01225 466000 [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com 1. AESOP. Aesop's Fables. With Instructive Morals and Reflections, Abstracted from all Party Considerations, Adapted To All Capacities; And designed to promote Religion, Morality, and Universal Benevolence. Containing Two Hundred and Forty Fables, with a Cut Engrav'd on Copper to each Fable. And the Life of Aesop prefixed, by Mr. Richardson. Engraved title-page and 25 plates each with multiple images. 8vo. [173 x 101 x 20 mm]. xxxiii, [iii], 192pp. Bound in contemporary mottled calf, the spine divided into six panels with raised bands and gilt compartments, lettered in the second on a red goatskin label, the others tooled in gilt with a repeated circular tool, the edges of the boards tooled with a gilt roll, plain endleaves and edges. (Rubbed, upper headcap chipped). [ebc6890] London: printed for J. Rivington, R. Baldwin, J. Hawes, W. Clarke, R. Collins, T. Caslon, S. Crowder, T. Longman, B. Law, R. Withy, J. Dodsley, G. Keith, G. Robinson, J. Roberts, & T. Cadell, [1760?]. £1000 A very good copy. With the early ink signature of Mary Ann Symonds on the front free endleaf. This is the fourth of five illustrated editions with the life by Richardson. It was first published in 1739 (title dated 1740), and again in 1749, 1753 (two issues) and 1775. All editions are rare, with ESTC listing four copies of the first, two of the second, five of the third and six of the fifth. -

Pre-Raphaelite Poetry

Dr.Pem Prakash Pankaj Asst.Professor,English Dept Vanijya Mahavidyalaya,PU Mob-8210481859 [email protected] For B.A (English Hons.) Part-1/ English Alternative Part-1 (50 marks) PRE-RAPHAELITE POETRY The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens and Thomas Woolner who formed a seven-member "Brotherhood" modelled in part on the Nazarene movement. The Brotherhood was only ever a loose association and their principles were shared by other artists of the time, including Ford Madox Brown, Arthur Hughes and Marie Spartali Stillman. Later followers of the principles of the Brotherhood included Edward Burne-Jones, William Morris and John William Waterhouse. Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), founded in September 1848, is the most significant British artistic grouping of the nineteenth century. Its fundamental mission was to purify the art of its time by returning to the example of medieval and early Renaissance painting. Although the life of the brotherhood was short, the broad international movement it inspired, Pre-Raphaelitism, persisted into the twentieth century and profoundly influenced the aesthetic movement, symbolism, and the Arts and Crafts movement. First to appear was Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849), in which passages of striking naturalism were situated within a complex symbolic composition. Already a published poet, Rossetti inscribed verse on the frame of his painting. In the following year, Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents (1850) was exhibited at the Royal Academy to an outraged critical reception. -

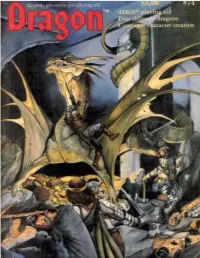

DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) Is Pub- the Occasion, and It Is Now So Noted

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chid: Kim Mohan Quiet celebration Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp Birthdays dont hold as much meaning Patrick L. Price Vol. VII, No. 12 June 1983 for us any more as they did when we were Mary Kirchoff younger. That statement is true for just Office staff: Sharon Walton SPECIAL ATTRACTION about all of us, of just about any age, and Pam Maloney its true of this old magazine, too. Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel June 1983 is the seventh anniversary of The DRAGON Magazine Contributing editors: Roger Moore Combat Computer . .40 Ed Greenwood the first issue of DRAGON Magazine. A playing aid that cant miss National advertising representative: In one way or another, we made a pretty Robert Dewey big thing of birthdays one through five c/o Robert LaBudde & Associates, Inc. if you have those issues, you know what I 2640 Golf Road mean. Birthday number six came and OTHER FEATURES Glenview IL 60025 Phone (312) 724-5860 went without quite as much fanfare, and Landragons . 12 now, for number seven, weve decided on Wingless wonders This issues contributing artists: a quiet celebration. (Maybe well have a Jim Holloway Phil Foglio few friends over to the cave, but thats The electrum dragon . .17 Timothy Truman Dave Trampier about it.) Roger Raupp Last of the metallic monsters? This is as good a place as any to note Seven swords . 18 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- the occasion, and it is now so noted. Have Blades youll find bearable lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per a quiet celebration of your own on our year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR behalf, if youve a mind to, and I hope Hobbies, Inc.