On Byzantine Churches, and the Modifications Made in Their Arrange- Ments Owing to the Necessities of the Greek Ritual.—By EDWIN PRESHFIELD, ESQ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Architectural and Functional/Liturgical Development of the North-West Church in Hippos (Sussita) 148 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK

CENTRE D’ARCHÉOLOGIE MÉDITERRANÉENNE DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXII 2008 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK Architectural and Functional/Liturgical Development of the North-West Church in Hippos (Sussita) 148 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK In July 2007, the eighth season of excavations was completed at the so-called North- West Church at Hippos (Sussita), one of the cities of the Decapolis. The church was explored by a Polish team within the framework of an international project devoted to the unearth- ing of the remains of that Graeco-Roman and Byzantine-Umayyad period town, headed by Arthur Segal of the University of Haifa. Despite the fact that as many as four churches have so far been uncovered at Sussita,1 it is only the North-West Church (NWC) that became one of the examples discussed by A. Ovadiah in his paper listing Byzantine-peri- od churches excavated within the borders of the present-day Israel, in which architectural changes apparently refl ect some liturgical modifi cations.2 Unfortunately, A. Ovadiah’s interpretation of the NWC (published in 2005) not only was based on the reports of the early seasons of our fi eldwork (2002, 2003), but also proved to be rather superfi cial one, a fact which calls for a careful re-examination of the excavation data. Perhaps the most important fact about the NWC is that this has been one of rare in- stances attested for the region of a church that was still active as such during the Um- ayyad period. Archaeological contexts sealed by the earthquake of A.D. -

The Spread of Christianity in the Eastern Black Sea Littoral (Written and Archaeological Sources)*

9863-07_AncientW&E_09 07-11-2007 16:04 Pagina 177 doi: 10.2143/AWE.6.0.2022799 AWE 6 (2007) 177-219 THE SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY IN THE EASTERN BLACK SEA LITTORAL (WRITTEN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOURCES)* L.G. KHRUSHKOVA Abstract This article presents a brief summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the eastern Black Sea littoral during the early Christian era (4th-7th centuries AD). Colchis is one of the regions of the late antique world for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Developments during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enable this process to be described in considerably greater detail The eastern Black Sea littoral–ancient Colchis–comprises (from north to south) part of the Sochi district of the Krasnodar region of the Russian Federation as far as the River Psou, then Abkhazia as far as the River Ingur (Engur), and, further south, the western provinces of Georgia: Megrelia (Samegrelo), Guria, Imereti and Adzhara (Fig. 1). This article provides a summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the region during the early Christ- ian era (4th-7th centuries AD).1 Colchis is one of the regions of late antiquity for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Progress during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enables this process to be described in considerably greater detail.2 The many early Christian monuments of Colchis are found in ancient cities and fortresses that are familiar through the written sources.3 These include Pityus (modern Pitsunda, Abkhazian Mzakhara, Georgian Bichvinta); Nitike (modern Gagra); Trakheia, which is surely Anakopiya (modern Novyi Afon, Abkhazian Psyrtskha); Dioscuria/ * Translated from Russian by Brent Davis. -

Swinging Thuribles in Early Byzantine Churches in the Holy Land. Author

Восточнохристианское искусство 119 УДК: 7.033.2…1 ББК: 85.13 А43 DOI:10.18688/aa166-2-12 Fanny Vitto Swinging Thuribles in Early Byzantine Churches in the Holy Land Swinging thuribles producing fragrant smoke are commonplace in the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Armenian, and Roman Catholic Churches. The use of incense, though, predates Christianity by thousands of years. The practice of incense burning during religious ceremonies was customary for most ancient civilizations around the Mediterranean. It orig- inated in the Near East, doubtlessly because its ingredients, frankincense and spices, were indigenous to this area. Frankincense is an aromatic resin obtained from the Boswellia sacra tree which grew mainly in southern Arabia and southern Nubia. Isaiah (Isaiah 60:6) speaks of the caravans of camels from Midian and Sheba carrying gold and frankincense. Incense was a greatly valued commodity in the ancient times. It is quite significant that frankincense (λίβανος) was one of the three gifts the Magi offered to infant Jesus (Matthew 2:11). In antiquity, incense was burned in various vessels including high clay stands, tripods with holes and horned altars. The Old Testament contains numerous references to the use of in- cense in Ancient Israel [9; 15; 23]. There were two terms for incense used in Hebrew: qetoret (a burning mixture of spices) and levonah (meaning white, i.e., frankincense which is one of the ingredients in qetoret). In the Temple of Jerusalem incense was burned by the High Priest in the Holy of Holies. On the Day of Atonement, the smoke of incense (qetoret sammim) sym- bolically carried men’s prayers to God in order to obtain forgiveness for their sins. -

Hymns of the Holy Eastern Church

Hymns of the Holy Eastern Church Author(s): Brownlie, John Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: Translations, selections, and suggestions based on hymns in the Greek service books. "Brownlie©s translations have all the beauty, simplicity, earnestness, and elevation of thought and feeling which characterize the originals" [Julian©s Diction- ary of Hymnology] Subjects: Practical theology Worship (Public and Private) Including the church year, Christian symbols, liturgy, prayer, hymnology Hymnology Hymns in languages other than English i Contents Front Page 1 Hymns of the Holy Eastern Church 2 Title Page 2 Preface 3 Greek Index 5 Introduction 7 The Eastern Church 8 The Eastern Churches 12 Sacraments and Vestments 15 Church Architecture 22 Service Books 24 Veneration of Saints 25 The Greek and Roman Churches 26 Forms of Hymnody 27 Hymns 31 Antiphon A (From the Office of Dawn) 32 Antiphon B (From the Office of Dawn) 33 Antiphon G (From the Office of Dawn) 34 Troparia 35 Troparion from the Third Canonical Hour 36 Kontakion-Automelon 37 Sticheron Idiomelon (Hymn of Anatolius) 38 Apolutikion 39 Troparia (From the Canon for Apocreos): Ode I 40 Troparia (From the Canon for Apocreos): Ode III 41 Stichera of Apocreos 42 ii Stichera of Apocreos 43 From the ΚΥΡΙΑΚΗ ΤΗΣ ΤΥΡΙΝΗΖ: Ode I 44 From the ΚΥΡΙΑΚΗ ΤΗΣ ΤΥΡΙΝΗΖ: Ode VII 45 Sticheron from the ΚΥΡΙΑΚΗ ΤΗΣ ΤΥΡΙΝΗΣ 46 Troparia (from the Canon of the Resurrection): Ode IV 47 Troparia (from the Canon of the Resurrection): Ode VII 48 Troparia (from the Canon of the Resurrection): Ode VIII 49 Stichera (Sung after the Canon for Easter Day) 50 Sticheron of the Resurrection 51 Stichera of the Resurrection 52 Stichera of the Resurrection 53 Apolutikion of the Resurrection 54 Stichera Anatolika 55 Stichera of the Ascension 57 Hymn to the Trinity 58 Hymn to the Trinity 59 Hymn to the Trinity 60 Order of Holy Unction 61 Order of Holy Unction 62 From the Canon of the Dead: Ode VIII 63 Idiomela of S. -

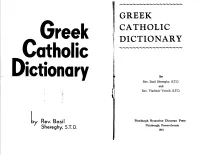

Dictionary of Byzantine Catholic Terms

~.~~~~- '! 11 GREEK CATHOLIC -reek DICTIONARY atholic • • By 'Ictionary Rev. Basil Shereghy, S.T.D. and f Rev. Vladimir Vancik, S.T.D. ~. J " Pittsburgh Byzantine Diocesan Press by Rev. Basil Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Shereghy, S.T.D. 1951 • Nihil obstat: To Very Rev. John K. Powell Censor. The Most Reverend Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Imprimatur: t Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Titular Bishop of Europus, Apostolic Exarch. Ordinary of the Pittsburgh Exarchate Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania of the Byzantine.•"Slavonic" Rite October 18, 1951 on the occasion of the solemn blessing of the first Byzantine Catholic Seminary in America this DoaRIer is resf1'eCtfUflY .diditateit Copyright 1952 First Printing, March, 1952 Printed by J. S. Paluch Co•• Inc .• Chicago Greek Catholic Dictionary ~ A Ablution-The cleansing of the Because of abuses, the Agape chalice and the fin,ers of the was suppressed in the Fifth cen• PREFACE celebrant at the DiVIne Liturgy tury. after communion in order to re• As an initial attempt to assemble in dictionary form the more move any particles of the Bless• Akathistnik-A Church book con• common words, usages and expressions of the Byzantine Catholic ed Sacrament that may be ad• taining a collection of akathists. Church, this booklet sets forth to explain in a graphic way the termin• hering thereto. The Ablution Akathistos (i.e., hymns)-A Greek ology of Eastern rite and worship. of the Deacon is performed by term designating a service dur• washmg the palm of the right ing which no one is seated. This Across the seas in the natural home setting of the Byzantine• hand, into .••••.hich the Body of service was originally perform• Slavonic Rite, there was no apparent need to explain the whats, whys Jesus Christ was placed by the ed exclusively in honor of and wherefores of rite and custom. -

Byzan2ne Architecture

Byzan&ne architecture S Vitale Ravenna apse prothesis diaconicon presbytery The apse is flanked by two chapels, the prothesis and the diaconicon, typical for Byzantine architecture. justinian matrimoneum Nave : South-East Apse : Each span, except Nave, has a semicircle apse. ecclesiastial eschatology The early Chris&an basilica was the way of realising Chris&an architecture needs within the limita&ons of the Roman architectural outlook the ideal byzantine church Hagia Sophia, Ayasofya, “Holy Wisdom”, Sancta Sophia The Central Plan The Dome Ligh&ng and decora&on the ideal byzantine church spiritually occupied Charlemagne aka in Latin: Carolus Magnus or Karolus Magnus, meaning Charles the Great 20 21 Blue Mosque Byzan&ne architecture strongly influenced the development of mosques, from Cairo to Turkey. Moorish architecture, reached its acme with the Alhambra in Granada. Suleyman Mosque Alhambra Taj Mahal Pala&ne Chapel, Aachen - Throne of Charlemagne Pala&ne Chapel, Aachen St Augus&ne’s City of God Plan of St. Gall Romanesque architecture is the term that is used to describe the architecture of Middle Ages Europe which evolved into the Gothic style beginning in the 12th century. The term "Romanesque", meaning "descended from Roman", was used to describe the style from the early 19th century. Although there is no consensus for the beginning date of the style, with proposals ranging from the 6th to the 10th centuries, examples can be found across the continent, making Romanesque architecture the first pan-European architectural style since Imperial Roman Architecture. The Romanesque style in England is more traditionally referred to as Norman architecture. Combining features of contemporary Western Roman and Byzantine buildings, Romanesque architecture is known by its massive quality, its thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers and decorative arcading. -

8 Heaven on Earth

Heaven on Earth The Eastern part of the Roman empire from the mid 5th century to the mid 15th century is referred to as the Byzantine Empire [62] but that term 8 would not have meant anything to the people living either in the Eastern or the Western parts of the Roman Empire at the time. The residents of the East thought of them- 62 selves as “Romans” as Map of the maximum extent much as the residents of of the Byzantine Empire (edited map: xenohistorian.faithweb.com/ the West did. In fact, Con- europe/eu08.html) stantine the Great had The Byzantine Empire expanded moved the capital of the and contracted many times from Roman Empire in 330 476, when the last emperor of the from “old” Rome in the Western Roman Empire abdi- West to what he called cated, until its demise in 1453. The “New” Rome (Nova map gives us some idea of the core of the Byzantine Empire’s Roma) in the East. There political and cultural influence. was already a city in the new location, Byzantion, and that is where the term Byzantine comes from. The name Constantinople was given to the new capital after the death of Constantine. Constantinople grew in power, cultural, and diplo- matic influence while old Rome was repeatedly plundered by barbarians. By the end of the 5th century the Western Roman Empire was out of busi- ness. So it was that the citizens in the East saw themselves as simply the continuation of the Roman Empire. We call that remnant of the old em- pire in the east, Byzantium, in recognition of the changed political situa- tion centered on Constantinople between 476 and 1453. -

St. Ambrose and the Architecture of the Churches of Northern Italy : Ecclesiastical Architecture As a Function of Liturgy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2008 St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy. Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider 1948- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Schneider, Sylvia Crenshaw 1948-, "St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1275 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B.A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2008 Copyright 2008 by Sylvia A. Schneider All rights reserved ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B. A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Approved on November 22, 2008 By the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________ Dr. -

Abadah Ibn Al-Samit, 1528 Abadion, Bishop of Antinoopolis, 1551 Abadir

Index Page numbers in boldface indicate a major discussion. Page numbers in italics indicate illustrations. A_______________________ Aaron at Philae, Apa, 1955 Ababius, Saint, 1, 2081 ‘Abadah ibn al-Samit, 1528 Abadion, Bishop of Antinoopolis, 1551 Abadir. See Ter and Erai, Saints Abadyus. See Dios, Saint Abamu of Tarnut, Saint, 1, 1551 Abamun of Tukh, Saint, 1-2, 1551 Abarkah. See Eucharistic wine Abba origin of term, 2-3 see also Proestos; specific name inverted Abba Maqarah. See Macarius II ‘Abbas Hilmi I Khedive, 1467,1636, 1692 ‘Abbas Hilmi II, Khedive, 1693, 1694, 1988 Abbasids compared with Umayyad administration, 2287 and Islamization, 937 Tulunid and Ikhshid rule, 2280-2281 Abbaton, 2, 1368, 1619 Abbot, 2-3 hegumenos and, 1216 provost and, 2024 see also Abba; specific names inverted ‘Abdallah, 3 ‘Abdallah Abu al-Su‘ud, 1993 ‘Abdallah ibn Musa, 3-4 ‘Abdallah ibn al-Tayyib, 6, 1777 Vol 1: pp. 1-316. Vol 2: pp. 317-662. Vol.3: pp. 663-1004 Vol 4: pp. 1005-1352. Vol 5: pp. 1353-1690. Vol 6: pp. 1391-2034. Vol 7: pp. 2035-2372 ‘Abdallah Nirqi, 4 evidence of Nubian liturgy at, 1817 example of Byzantine cross-in-square building at, 661 Nubian church art at, 1811-1812 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz, Sultan, 893 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn Marwan (Arab governor of Egypt), 85, 709, 1303 ‘Abd al-‘Aziz ibn Sa‘d al-Din, 5 Abdelsayed, Father Gabriel, 1621 ‘Abd al-Malak, Saint, 840 ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan, Caliph, 239, 937 ‘Abd al-Malik ibn Musa ibn Nasir, Caliph, 1411 ‘Abd al-Masih (manuscript), 5 ‘Abd al-Masih,Yassa, 1911 doxologies studied by, 1728 ‘Abd al-Masih ibn Ishaq al-Kindi, 5 ‘Abd al-Masih al-Isra’ili al-Raqqi, 5-7 ‘Abd al-Masih, known as Ibn Nuh, 7 ‘Abd al-Masih Salib al-Masu‘di, 7, 14, 1461 on Dayr al-Jarnus, 813 on Dayr al-Khadim and Dayr al-Sanquriyyah, 814 on Dayr Sitt Dimyanah, 870, 871 and Iqladiyus Labib, 1302 and Isidhurus, 1307 on Jirjis al-Jawhari al-Khanani, 1334 on monastery of Pisentius, 757 ‘Abd al-Raziq, ‘Ali, 1996 ‘Abd al-Sayyid, Mikha’il, 1465, 1994 ‘Abduh, Muhammad, 1995 Abednego, 1092 Abfiyyah (martyr), 1552 Abgar, King of Edessa, 7-8, 1506 Abib. -

Relationship Between Traditional and Contemporary Elements in the Architecture of Orthodox Churches at the Turn of the Millennium Udc 726.5

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Architecture and Civil Engineering Vol 13, No 3, 2015, pp. 283 - 300 DOI: 10.2298/FUACE1503283M RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TRADITIONAL AND CONTEMPORARY ELEMENTS IN THE ARCHITECTURE OF ORTHODOX CHURCHES AT THE TURN OF THE MILLENNIUM UDC 726.5 Bozidar Manic, Ana Nikovic, Igor Maric Institute of Architecture and Urban & Spatial Planning of Serbia (IAUS), Belgrade, Serbia Abstract. The paper will present the contemporary practice of church architecture in Bulgarian, Romanian, Russian and Greek orthodox churches, at the end of the XX and the beginning of the XXI century, and analyse the relationship of traditional and contemporary elements, with the aim of determining main trends and development tendencies. Free development of sacred architecture was interrupted by long reigns of authorities opposed to Orthodox Christianity. After the downfall of Communist regimes, conditions were created for the unobstructed construction of sacred buildings in all Orthodox countries, while the issue of traditional church architecture re-emerged as important. Further development of Orthodox church architecture may be affected by some issues raised in relation to the structure and form of liturgy, regarding the internal organisation of the temple. The freedom of architectural creation is strongly supported by the richness of forms created throughout history. Traditionalist approaches to the architectural shaping of churches are dominant even nowadays, tradition being understood and interpreted individually. At the same time, efforts to -

The Liturgies of SS. Mark, James, Clement, Chrysostom, and Basil

UUSB LIBHAKY TEE LITURGIES OF SS. MARK, JAMES, CLEMENT, OHRYSOSTOM, AND BASIL, AND THE CHURCH OF MALABAR EXPLANATION OF FHONTISPIECE. THE FRONTISPIECE is taken from one of the series ol nine plates in a beautiful MS. of the Greek Liturgies now in the Vatican; hut, in A.D. 1600, in the Monastery of S. Mary at Cardinal Gethsemane. ; They have been engraved by Mai, in the Sixth volume- of the "NovaBibliqtheca." The intention of the designer is to show tlie fellow-ministration of angels with men in the Liturgy. This plate (the sixth) represents the GREAT ENTRANCE : (see pp. xxix. and 108). The Priest, carried by angels, brings in the chalice covered with the aer : in his right hand, he holds the paten, covered with its veil. The door, out of which he comes, is that of the prothesis. The Deacon, with a taper, and the stole marked with the Ter Sanctns, bows. To the right, an archimandrite stands up: " by him is S. Michael : in answer to the prayer, Grant that with our entrance may be an entrance of the holy angels." In front of the altar, the Priest is represented again : he wears the alb over it a or chasuble : stoicharion, or ; plain pJuelonion, on his left (by the designer's mistake for his right) is seen a part of the epigonation. On the altar are the two tapers : the chalice, covered with the aer; the asterisk covered with the veil ; and behind, the books of the Epistles and Gospels. The Great Entrance, as we shall see, is the grandest piece of ritual in the Eastern Church, and mystically represents the Incarnation. -

Byzantine Church Decoration and the Great Schism of 1054 *

Alexei LIDOV BYZANTINE CHURCH DECORATION AND THE GREAT SCHISM OF 1054 * in Byzantion, LXVIII/2 (1998), pp.381-405 We can hardly overestimate the importance of changes that befell Byzantine church decoration in the 11th and 12th centuries--the time when a system was symbolically centered round the "Communion of the Apostles" above the altar. Despite age-old additions, it survived as the basis of the Orthodox Christian iconographic program. No less importantly, it was this new system that determined the disagreement in principles which made the Western Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions of church decorations part ways. The link between iconographic novelties and the liturgy has been amply demonstrated in scholarly literature1. Among the first was A. Grabar's work about the Jerusalem liturgical scroll2. G. Babic's article about the Officiating Bishops as connected with the Christological polemics of the 12th century notably influenced her researcher colleagues3. Chr. Walter's book Art and Ritual of the Byzantine Church4 offered a system of liturgical themes. A number of authors brought out and analyzed a range of iconographic themes and motifs to be explained by the contemporaneous liturgical context. Among these, we can single out studies of the image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows5, the Lamentation scene6, the particular iconographic types of Christ the High Priest consecrating the Church and Christ the Priest7. In fact, every serious study of an 11th or 12th century monument adds something new to our knowledge of the liturgical influences on church decoration. The new liturgical themes came down to us in non-contemporaneous monuments of the 11th and 12th centuries.