Swinging Thuribles in Early Byzantine Churches in the Holy Land. Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vespers Program Print 31MAR

HYMNS March 24: O God, Why Are You Silent 1. O God, why are you silent? I cannot hear your voice. The proud and strong and violent All claim you and rejoice. You promised you would hold me With tenderness and care. Draw near, O Love, enfold me, And ease the pain I bear. 2. Now lost within my grieving, I fall and lose my way. My fragile, faint believing So swiftly swept away. O God of pain and sorrow, My compass and my guide, I cannot face the morrow Without you by my side. 4. Through endless nights of weeping, This worship aid will suffice for all six weeks of Vespers. Just scroll Through weary days of grief, down until you see the appropriate date for each song or prayer. My heart is in your keeping, My comfort, my relief. Come, share my tears and sadness, Come, suffer in my pain; O bring me home to gladness, Restore my hope again. 5. May pain draw forth compassion, Let wisdom rise from loss. O take my heart and fashion The image of your cross. Then may I know your healing Through healing that I share, Your grace and love revealing Your tenderness and care. Text: Marty Haugen, b. 1950, © 2003, GIA Publications, Inc. EVENING THANKSGIVING PSALMS Each night, we begin with Psalm 141, and incense is placed in the censer to suggest our prayers rising to God. At the end of this and each psalm, there is a prayer by the presider. Every night: Psalm 141 Evening Offering March 31: Psalm 23 Shepherd Me, O God READING MAGNIFICAT (next page) INTERCESSIONS THE LORD’S PRAYER CLOSING PRAYER Presider: Our help is in the name of the Lord. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

The Offering of Incense) Thurification Or Incensation Is an Expression of Reverence and of Prayer, As Is Signified in Sacred Scripture…Psalm 141; Revelation 8:3 1

Thurifer Procedures Preparing for Mass *Attire…dress as you would…when serving as Acolyte *Arrive inside church at a minimum 45 minutes before the start of Mass. *Position Censer Stand near Ambo/Lectern/Pulpit. You will need easy access to return boat before Gospel reading. Gather the following in Sacristy: *Thurible… (Metal censer suspended from chains) --Contains 4 items: Base; Tray; Top; Chains --If necessary, you may need to clean out any unburnt coals from the tray. You can dispense the coals directly in to the trash…please insure coals have been cooled. If not…place in sink, flow water over them. --Lighter…make certain it flames --Boat…contains the incense. Fill boat with incense --Spoon…position spoon in boat --Charcoal…2 discs Lighting of charcoal…10 minutes prior to start of Mass or Procession Service --Use tongs...with Star facing down…hold charcoal disc below countertop level. --Place lighter on underside of disc…the charcoal will flare…sparks will come off disc…continue to light until sparks have stopped. Slightly blow on disc to insure it is burning --Place charcoal disc inside tray…star side facing up. --Place charcoal discs side by side…not on top of each other --close top…exit Sacristy…start to ‘swing’ thurible Incensation (The offering of Incense) Thurification or Incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture…Psalm 141; Revelation 8:3 1. During the entrance procession; 2. At the beginning of Mass; to incense the cross and the altar; 3. At the procession before the Gospel and the proclamation of the Gospel itself; 4. -

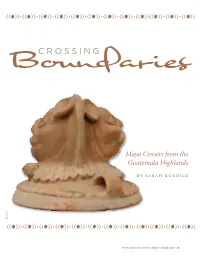

CROSSING Boundaries

(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) CROSSING Boundaries Maya Censers from the Guatemala Highlands by sarah kurnick k c i n r u K h a r a S (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) www.museum.upenn.edu/expedition 25 (( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o))(( o)) •(( o)) •(( o)) he ancient maya universe consists of three realms—the earth, the sky, and the Under- world. Rather than three distinct domains, these realms form a continuum; their bound - aries are fluid rather than fixed, permeable Trather than rigid. The sacred Tree of Life, a manifestation of the resurrected Maize God, stands at the center of the universe, supporting the sky. Frequently depicted as a ceiba tree and symbolized as a cross, this sacred tree of life is the axis-mundi of the Maya universe, uniting and serving as a passage between its different domains. For the ancient Maya, the sense of smell was closely related to notions of the afterlife and connected those who inhabited the earth to those who inhabited the other realms of the universe. Both deities and the deceased nour - ished themselves by consuming smells; they consumed the aromas of burning incense, cooked food, and other organic materials. Censers—the vessels in which these objects were burned—thus served as receptacles that allowed the living to communicate with, and offer nour - ishment to, deities and the deceased. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology currently houses a collection of Maya During the 1920s, Robert Burkitt excavated several Maya ceramic censers excavated by Robert Burkitt in the incense burners, or censers, from the sites of Chama and Guatemala highlands during the 1920s. -

Swift Censer

Why incense? FIVE REASONS FROM SCRIPTURE Incense was a regular part of the worship of Lutherans in the early Reformation, which probably shouldn’t be surprising. They were used to it, there was no need to reject it, and the Bible provides clear reasons for using it. So what does the Bible say about incense? It has a long history. Holy The use of incense for the worship of the One True God extends from the Old Testament into the New. See, for instance, Ex. 30:7-8: “And Aaron shall burn fragrant incense on it [the altar]. Every SMOKE morning when he dresses the lamps he shall burn it, and when Aaron sets up the lamps at twilight, he shall burn it, a regular incense offering before the Lord throughout your generations.” See also 2 Chron. 13:11; Phil. 4:18. The Bible speaks highly of it. It signals God’s presence. Luther recommended it. Why not Throughout Scripture, incense marks the presence of the One True God. Ex. 40:34: “Then the cloud revive it here? covered the tent of meeting, and the glory of the Lord filled the tabernacle.” See also Is. 6; Matt. 2:11 You may have noticed a recent addition in our altar area—an ornate (the Magi offer frankincense and myrrh to the baby Jesus) and John 19:39 (Nicodemus brings myrrh brass pole standing roughly 5’ tall, with chains hanging from it, holding a and aloes for Christ’s burial). tear-shaped object. It’s a symbol of atonement. Maybe you’ve noticed the little “Aladdin’s lamp” there, too. -

Architectural and Functional/Liturgical Development of the North-West Church in Hippos (Sussita) 148 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK

CENTRE D’ARCHÉOLOGIE MÉDITERRANÉENNE DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXII 2008 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK Architectural and Functional/Liturgical Development of the North-West Church in Hippos (Sussita) 148 JOLANTA MŁYNARCZYK In July 2007, the eighth season of excavations was completed at the so-called North- West Church at Hippos (Sussita), one of the cities of the Decapolis. The church was explored by a Polish team within the framework of an international project devoted to the unearth- ing of the remains of that Graeco-Roman and Byzantine-Umayyad period town, headed by Arthur Segal of the University of Haifa. Despite the fact that as many as four churches have so far been uncovered at Sussita,1 it is only the North-West Church (NWC) that became one of the examples discussed by A. Ovadiah in his paper listing Byzantine-peri- od churches excavated within the borders of the present-day Israel, in which architectural changes apparently refl ect some liturgical modifi cations.2 Unfortunately, A. Ovadiah’s interpretation of the NWC (published in 2005) not only was based on the reports of the early seasons of our fi eldwork (2002, 2003), but also proved to be rather superfi cial one, a fact which calls for a careful re-examination of the excavation data. Perhaps the most important fact about the NWC is that this has been one of rare in- stances attested for the region of a church that was still active as such during the Um- ayyad period. Archaeological contexts sealed by the earthquake of A.D. -

The Spread of Christianity in the Eastern Black Sea Littoral (Written and Archaeological Sources)*

9863-07_AncientW&E_09 07-11-2007 16:04 Pagina 177 doi: 10.2143/AWE.6.0.2022799 AWE 6 (2007) 177-219 THE SPREAD OF CHRISTIANITY IN THE EASTERN BLACK SEA LITTORAL (WRITTEN AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOURCES)* L.G. KHRUSHKOVA Abstract This article presents a brief summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the eastern Black Sea littoral during the early Christian era (4th-7th centuries AD). Colchis is one of the regions of the late antique world for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Developments during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enable this process to be described in considerably greater detail The eastern Black Sea littoral–ancient Colchis–comprises (from north to south) part of the Sochi district of the Krasnodar region of the Russian Federation as far as the River Psou, then Abkhazia as far as the River Ingur (Engur), and, further south, the western provinces of Georgia: Megrelia (Samegrelo), Guria, Imereti and Adzhara (Fig. 1). This article provides a summary of the literary and archaeological evidence for the spread and consolidation of Christianity in the region during the early Christ- ian era (4th-7th centuries AD).1 Colchis is one of the regions of late antiquity for which the archaeological evidence of Christianisation is greater and more varied than the literary. Progress during the past decade in the field of early Christian archaeology now enables this process to be described in considerably greater detail.2 The many early Christian monuments of Colchis are found in ancient cities and fortresses that are familiar through the written sources.3 These include Pityus (modern Pitsunda, Abkhazian Mzakhara, Georgian Bichvinta); Nitike (modern Gagra); Trakheia, which is surely Anakopiya (modern Novyi Afon, Abkhazian Psyrtskha); Dioscuria/ * Translated from Russian by Brent Davis. -

A Concise Glossary of the Genres of Eastern Orthodox Hymnography

Journal of the International Society for Orthodox Church Music Vol. 4 (1), Section III: Miscellanea, pp. 198–207 ISSN 2342-1258 https://journal.fi/jisocm A Concise Glossary of the Genres of Eastern Orthodox Hymnography Elena Kolyada [email protected] The Glossary contains concise entries on most genres of Eastern Orthodox hymnography that are mentioned in the article by E. Kolyada “The Genre System of Early Russian Hymnography: the Main Stages and Principles of Its Formation”.1 On the one hand the Glossary is an integral part of the article, therefore revealing and corroborating its principal conceptual propositions. However, on the other hand it can be used as an independent reference resource for hymnographical terminology, useful for the majority of Orthodox Churches worldwide that follow the Eastern Rite: Byzantine, Russian, Bulgarian, Serbian et al., as well as those Western Orthodox dioceses and parishes, where worship is conducted in English. The Glossary includes the main corpus of chants that represents the five great branches of the genealogical tree of the genre system of early Christian hymnography, together with their many offshoots. These branches are 1) psalms and derivative genres; 2) sticheron-troparion genres; 3) akathistos; 4) canon; 5) prayer genres (see the relevant tables, p. 298-299).2 Each entry includes information about the etymology of the term, a short definition, typological features and a basic statement about the place of a particular chant in the daily and yearly cycles of services in the Byzantine rite.3 All this may help anyone who is involved in the worship or is simply interested in Orthodox liturgiology to understand more fully specific chanting material, as well as the general hymnographic repertoire of each service. -

St. Mary's Altar Server Manual

ABOUT SERVING St. Mary’s By serving at the altar, you are participating in the greatest mystery of our faith: that God would come to dwell among us and offer his divine Son as a sacrifice for our redemption. Serving well allows everyone to pray reverently and maintains the dignity of the Mass. A good server is attentive Cathedral to the liturgy and able to move when needed without drawing attention to him/herself. Serving at the altar is an honor that is not open to everyone. Always conduct yourself in a way that commands respect, maintaining an attitude of honor and respect. Altar servers help everyone pray and worship God, but especially assist the priest in the celebration of the sacred mysteries. Everything in the liturgy is directed to manifesting the glory of God. Servers should be mature enough to understand their responsibilities and to carry them out well in a graceful and reverent way. They should ordinarily have already been admitted to receiving Holy Communion. Servers should receive proper formation before they begin to function. The formation should include instruction on the Mass and its parts and their meaning, the various objects used in the liturgy (their names and use), and the various functions of the server during the Mass and other liturgical celebrations. Servers should also receive appropriate guidance on maintaining proper decorum and attire when serving Mass and other functions. Since the role of server is integral to the normal celebration of the Mass, at least one server should assist the priest. On Sundays and other more important occasions, two or more servers should be employed to carry out the various functions normally entrusted to these ministers. -

Altar Boy Manual

ALTAR SERVERS MANUAL Before Liturgy starts Altar Servers should: 1. Have robe blessed 2. Light processional candles 3. Fill coffee pot with water 4. Older Altar Servers cut Holy Bread as assigned by John and Bob 5. Older Altar Server lights censer Little Entrance: After the Priest says “Again and again in peace let us pray to the Lord” for second time you should get ready for the Little Entrance. The three servers doing this should line up at the North door, which is the door closest to the Table of Oblation. Things Needed: 2 candles and cross - see Figure 1 for where to walk. After the priest enters the sanctuary, bow before the Altar and enter the side doors as soon as the priest puts the Gospel on the altar. Candle holders should stand in back of the sanctuary, next to each outer red chair, in preparation for the Epistle & Gospel. The person holding the Cross holder returns the Cross to its stand. Epistle/Gospel Readings: When the Priest says “Dynamis” (Greek for “With Strength”), Candle holders should go out the door on the side they are standing and stand on either side of the Epistle reader - see Figure 2. Candle holders bow before the Altar and come in after Priest returns to the altar after reading the Gospel. Great Entrance: Immediately after the Gospel reading (or after Sermon, if done after the Gospel), line up for Great Entrance at the North door, which is the same side door as was used for the Little Entrance. Things Needed: 2 Candles, Cross, and two fans, who stand next to the Table of Oblation while the clergy is getting ready. -

On Byzantine Churches, and the Modifications Made in Their Arrange- Ments Owing to the Necessities of the Greek Ritual.—By EDWIN PRESHFIELD, ESQ

XXIV.— On Byzantine Churches, and the Modifications made in their Arrange- ments owing to the Necessities of the Greek Ritual.—By EDWIN PRESHFIELD, ESQ. M.A. F.S.A. Read April 3rd, 1873. There is no subject that appears to me to present a better field for inquiry to a Christian antiquary than the architecture and antiquities of the Byzantine Church and the Churches associated with it. Although much has no doubt been lost, much still remains, and a far from incomplete history of Byzantine architecture and of the different styles prevailing at the different epochs of that empire might be collected even from the churches still existing in the cities of Constantinople, Salonica, Athens, and Trebisond alone, and there would still remain the churches of the Monasteries of Mount Athos and of the islands, without touching upon those of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt. My object in this communication is to point out what I believe to be one of the great landmarks in the Byzantine style, and its connection with the Greek Liturgy. The landmark is this: where an ancient Greek church is found with three apses it is subsequent in date to the Emperor Justin II., or has had a new east end applied; where it has only one apse it is prior to that date. Byzantine architecture is so intimately connected with the Liturgy of its Church that the study of one necessarily involves the other. On examining the churches I was struck to find in the later buildings a dis- tinctive feature found equally at Corfu and Trebisond, at Alexandria and at Studenitza, which I did not find in the earlier examples, and this feature I will explain. -

Thurifer Procedures V2

Thurifer Procedures March 31, 2021 INTRODUCTION “Thurification or incensation is an expression of reverence and of prayer, as is signified in Sacred Scripture” (GIRM, 276). Incense is one of the oldest and richest signs of prayer and worship in our liturgy. We read about frankincense as one of the gifts of the Magi at the nativity of Our Lord. We read of the prayers of the faithful rising as incense in the throne-room of heaven in Revelations. It is a fragrant perfume offered to God. Incense is made from gum olibanum, a precious resin from the boswellia carterii bush in Southern Arabia. To this basic ingredient other spices are added to vary the perfume. The grains of incense, carried in the boat, are scooped into the thurible by the priest where they are burned on charcoal disks to create the incense smoke. Per the General Instruction of the Roman Missal (GIRM, 276), incense may be used optionally at any Mass: a) during the Entrance Procession; b) at the beginning of Mass, to incense the cross and the altar; c) at the procession before the Gospel and the proclamation of the Gospel itself; d) after the bread and the chalice have been placed on the altar, to incense the offerings, the cross, and the altar, as well as the Priest and the people; e) at the elevation of the host and the chalice after the Consecration. There is a long liturgical tradition of service at the altar for lay ministers (non- clergy), including lectors, sacristans, and altar servers. Thurifer is one of the more solemn and important roles for altar servers.