Jul-Dec2018.Pdf (1.234Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Schedule Chart (8 1/2 X 14 In

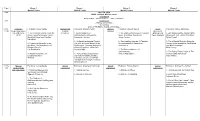

Time Room 1. Room 2. Room 3. Room 4. Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center Moffett Center 9:00 April 10, 2010 SUNY Cortland, Moffett Center Registration Sarat Colling - Elizabeth Green – Ashley Mosgrove 9:30 Introduction Anthony J. Nocella, II Welcoming Andrew Fitz-Gibbon and Mechthild Nagel 10:00 – Academic Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animals and Facilitator: Ronald Pleban Species Facilitator: Doreen Nieves Social Facilitator: Ashley Mosgrove 11:20 Repression Book Cultural Inclusion Movement Talk (AK Press, 1. The Carceral Society: From the Practices 1 Animal Subjects in 1. The Politics of Inclusion: A Feminist Strategy and 1. DIY Media and the Animal Rights 2010) Prison Tower to the Ivory Tower Anthropological Perspective Space to Critique Speciesism Tactic Analysis Movement: Talk - Action = Nothing Mechthild Nagel and Caroline Alessandro Arrigoni Jenny Grubbs Dylan Powell Kaltefleiter 2. An American Imperial Project: 2. Transcending Species: A Feminist 2. The Influential Activist: Using the 2. Regimes of Normalcy in the The Role of Animal Bodies in the Re-examination of Oppression Science of Persuasion to Open Minds Academy: The Experiences of Smithsonian-Theodore Roosevelt Jeni Haines and Win Campaigns Disabled Faculty African Expedition, 1909-1910. Nick Cooney Liat Ben-Moshe Laura Shields 3. The Reasonableness of Sentimentality 3. The Role of Direct Action in The 3. Adelphi Recovers „The 3. Conservation perspectives: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon Animal Rights Movement Lengthening View International wildlife priorities, Carol Glasser Ali Zaidi individual animals, and wildlife management strategies in Kenya Stella Capoccia 11:30- Species Facilitator: Jackie Riehle Animal Facilitator: Anastasia Yarbrough Animal Facilitator: Brittani Mannix Animal Facilitator: Andrew Fitz-Gibbon 1:00 Relationships Exploitation Exploitation Exploitation and Domination 1. -

Until One Has Loved an Animal, a Part of One's Soul Remains Unawakened

THEOSOPHICAL ORDER OF SERVICE, USA SPRING 2014 Until one has loved an animal, a part of one’s soul remains unawakened. —ANATOLE FRANCE For the Love of Life Contents Spring 2014 THEOSOPHICAL ORDER OF SERVICE, USA Editor Ananya S. Rajan 2 From the President’s Desk Designer Lindsay Freeman By Nancy Secrest OfficErs anD BOarD Of DirEctOrs 4 The Reason Why By RAdha Burnier President Nancy Secrest secretary Ananya S. Rajan 5 An Inside Look at Animals treasurer Betty Bland An Interview with Robyn Finseth Board Members Tim Boyd By Nancy Secrest Kathy Gann Jon Knebel Jeanne Proulx 9 To Ziggy with Love Honorary By AnanyA S. Rajan Board Members Joseph Gullo Miles Standish 12 Meet the Girls Contact information for the Theosophical By AnanyA S. Rajan Order of Service in the United States: Mailing address Theosophical Order 14 On Service Animals of Service 1926 N. Main St By Nancy Secrest Wheaton, IL 60187 send donations by 19 Do Animals Have Rights? check to: P.O. Box 1080 By Morry Secrest Wakefield, NC 27588 Phone 630-668-1571 ext. 332 22 Beagle Freedom Project E-mail [email protected] By Kathy Gann Website www.theoservice.org To leave a name for the Healing network: 23 Happy Birthday Jane 800-838-2197. For animal healing contact us at 25 Where the Wild Things Are [email protected] By AnanyA S. Rajan For more information about the TOS around the world, go to http://international. theoservice.org/ 28 Scholarship Recipients Disclaimer On the cOvEr: Articles and material in this publication do not necessarily Friends for Lifetimes--Bella with Tarra roam the grounds at reflect the opinions of the Theosophical Order of Service or The Elephant Sanctuary. -

I Mmmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I Mmmmmmmmmm 5A Gross Rents

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¼ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2018 or tax year beginning 02/01 , 2018, and ending 01/31 , 20 19 Name of foundation A Employer identification number SALESFORCE.COM FOUNDATION 94-3347800 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 50 FREMONT ST 300 (866) 924-0450 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption applicatmionm ism m m m m m I pending, check here SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94105 m m I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm hem rem anmd am ttamchm m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminamtedI Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminmatIion end of year (from Part II, col. -

Overcoming Sociological Naïveté in the Animal Rights Movement

Theory in Action, Vol. 9, No. 1, January (© 2016) DOI:10.3798/tia.1937-0237.16003 Overcoming Sociological Naïveté in the Animal Rights Movement Joseph H. Michalski* The following paper draws upon Milner’s theory of social status to explain why nonhuman animals generally are not accorded equal status or the same level of compassion as human beings. The inexpansible nature of status means that one’s position in a status hierarchy depends upon how one fares relative to everyone else. Acquiring status requires the ability to excel in terms of collective expectations, or the ability to conform appropriately to extant group norms. Moreover, social associations with high-status individuals usually further enhance one’s relative status. Animals are disadvantaged along each of these aspects of status systems in most cases. Moreover, their relational and cultural distance from human beings reinforces their inferior position, reducing the likelihood of human beings defining them as “innocent victims” or otherwise according them full and equal rights. Yet animal rights activists who are aware of these sociological realities will be in a better position to advocate more effectively on behalf of at least selected nonhuman species. [Article copies available for a fee from The Transformative Studies Institute. E-mail address: [email protected] Website: http://www.transformativestudies.org ©2016 by The Transformative Studies Institute. All rights reserved.] KEYWORDS: Animal Rights, Sociological Theory, Status, Nonhuman Species, Activism. * Joseph H. Michalski, Ph.D., is Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Sociology, King’s University College at Western in Ontario, Canada. His academic work focuses mainly on the development and application of sociological theory to explain variations in diverse forms of human behaviors, but especially with respect to different forms of violence. -

'Choctaw: a Cultural Awakening' Book Launch Held Over 18 Years Old?

Durant Appreciation Cultural trash dinner for meetings in clean up James Frazier Amarillo and Albuquerque Page 5 Page 6 Page 20 BISKINIK CHANGE SERVICE REQUESTED PRESORT STD P.O. Box 1210 AUTO Durant OK 74702 U.S. POSTAGE PAID CHOCTAW NATION BISKINIKThe Official Publication of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma May 2013 Issue Tribal Council meets in regular April session Choctaw Days The Choctaw Nation Tribal Council met in regular session on April 13 at Tvshka Homma. Council members voted to: • Approve Tribal Transporta- returning to tion Program Agreement with U.S. Department of Interior Bureau of Indian Affairs • Approve application for Transitional Housing Assis- tance Smithsonian • Approve application for the By LISA REED Agenda Support for Expectant and Par- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma 10:30 a.m. enting Teens, Women, Fathers Princesses – The Lord’s Prayer in sign language and their Families Choctaw Days is returning to the Smithsonian’s Choctaw Social Dancing • Approve application for the National Museum of the American Indian in Flutist Presley Byington Washington, D.C., for its third straight year. The Historian Olin Williams – Stickball Social and Economic Develop- Dr. Ian Thompson – History of Choctaw Food ment Strategies Grant event, scheduled for June 21-22, will provide a 1 p.m. • Approve funds and budget Choctaw Nation cultural experience for thou- Princesses – Four Directions Ceremony for assets for Independence sands of visitors. Choctaw Social Dancing “We find Choctaw Days to be just as rewarding Flutist Presley Byington Grant Program (CAB2) Soloist Brad Joe • Approve business lease for us as the people who come to the museum say Storyteller Tim Tingle G09-1778 with Vangard Wire- it is for them,” said Chief Gregory E. -

Animal-Industrial Complex‟ – a Concept & Method for Critical Animal Studies? Richard Twine

ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 Journal for Critical Animal Studies ISSN: 1948-352X Volume 10 Issue 1 2012 EDITORAL BOARD Dr. Richard J White Chief Editor [email protected] Dr. Nicole Pallotta Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Lindgren Johnson Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Laura Shields Associate Editor [email protected] Dr. Susan Thomas Associate Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Richard Twine Book Review Editor [email protected] Vasile Stanescu Book Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Carol Glasser Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Adam Weitzenfeld Film Review Editor [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Cole Web Manager [email protected] ___________________________________________________________________________ EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD For a complete list of the members of the Editorial Advisory Board please see the Journal for Critical Animal Studies website: http://journal.hamline.edu/index.php/jcas/index 1 Journal for Critical Animal Studies, Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 (ISSN1948-352X) JCAS Volume 10, Issue 1, 2012 EDITORAL BOARD .............................................................................................................. -

2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service 1-The Organization May Have to Use a Copy of This Return to Satisfy State Reporting Requirements

efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493227022653 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service 1-The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2012 calendar year, or tax year beginning 01-01-2012 , 2012, and ending 12-31-2012 C Name of organization B Check if applicable D Employer identification number Network for Good FAddresschange 68-0480736 Doing Business As F Name change 1 Initial return Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 1140 Connecticut Avenue NW No 700 F_ Terminated (888)284-7978 (- Amended return City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 Washington, DC 20036 1 Application pending G Gross receipts $ 171,608,968 F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for William Strathmann affiliates? 1 Yes F No 1140 Connecticut Avenue NW No 700 Washington, DC 20036 H(b) Are all affiliates included? 1 Yes (- No If "No," attach a list (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status F 501(c)(3) 1 501(c) ( ) I (insert no ) (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 H(c) Group exemption number 0- J Website : 1- www networkforgood org K Form of organization F Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association (- Other 0- L Year of formation 2001 M State of legal domicile DE Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities To unleash generosity and drive increased financial resources to charitable organizations via digital platforms w 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

West Hollywood First City in the Nation To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Angie Adamson Campaigns Director (O) 310-271-6096 x27 (C) 310-849-0174 [email protected] FUR FREE WEST HOLLYWOOD, CA, reports LCA The First City in the Nation to Ban the Sale of Fur Apparel West Hollywood, CA, September 22, 2011 - A precedent setting victory for the animals occurred at 1:15am Tuesday, 9/20/11, when, after a seven hour meeting, WeHo’s city council voted 5-0 to pass a ban on the sale of fur apparel. Following in the footsteps of the humane minded council who voted for the animals in 1989 and passed Resolution 558 proclaiming WeHo a cruelty free zone, the council made this historic vote and put their foot down against the barbaric fur trade. This historic vote makes West Hollywood the first city in the nation with such a ban, proving that West Hollywood is truly a cruelty free zone. Last Chance for Animals, Shannon Keith, Ellen Lavinthal, Ed Buck, and fellow animal advocates came together to make this ban possible. Preceding the historic vote this group held weekly rallies and demonstrations, and made visits to retail establishments carrying fur. Important objectives were met including several stores in WeHo voluntarily removing fur from their stores, fur free candidate John D’Amico being elected to the West Hollywood City Council, and raising awareness around the fur issue. Thanks to these efforts John D’Amico was able to introduce the ordinance to ban the sale of fur apparel in West Hollywood. This ordinance makes West Hollywood the first city to go fur free in the U.S., setting a precedent for the rest of the world to put an end to the needless suffering of fur bearing animals solely for the purposes of vanity. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax OMB No

Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501(c), 527, or 4947(a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code (except private foundations) 2013 Department of the Treasury | Do not enter Social Security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Open to Public Internal Revenue Service | Information about Form 990 and its instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990. Inspection A For the 2013 calendar year, or tax year beginning and ending B Check if C Name of organization D Employer identification number applicable: Address change Network for Good Name change Doing Business As 68-0480736 Initial return Number and street (or P.O. box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number Termin- ated 1140 Connecticut Avenue, NW 700 888-284-7978 Amended return City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code G Gross receipts $ 195,975,556. Applica- tion Washington, DC 20036 H(a) Is this a group return pending F Name and address of principal officer:Robert Deily for subordinates? ~~ Yes X No same as C above H(b) Are all subordinates included? Yes No I Tax-exempt status: X 501(c)(3) 501(c) ( )§ (insert no.) 4947(a)(1) or 527 If "No," attach a list. (see instructions) J Website: | www.networkforgood.org H(c) Group exemption number | K Form of organization: X Corporation Trust Association Other | L Year of formation: 2001 M State of legal domicile: DE Part I Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities: To unleash generosity and drive increased financial resources to charitable organizations via 2 Check this box | X if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets. -

Terrorists Or Freedom Fighters? Katrina Fox Talks to Women Who Risk Their Lives and Liberty to Save Animals

Words Katrina Fox TERRORISTS OR FREEDOM FIGHTERS? KATRINA FOX TALKS TO WOMEN WHO RISK THEIR LIVES AND LIBERTY TO SAVE ANIMALS Melanie Arnold is a 38-year-old manager of a small home for adults with act of terrorism. Vivisectors blinding kittens and electrocuting monkeys are learning difficulties and autism in the UK. It’s one of a string of jobs she’s had acts of terrorism. The ALF largely take rabbits, rats and dogs from facilities over the years as a carer and she’s currently two years into a naturopathy that are designed to study their torture. They take chickens and turkeys and Melanie Arnold Shannon Keith Sandra Mohr course with the aim of healing people with natural medicine. She is a spiritual sheep before they are boxed off to be decapitated. The ALF do not commit person with a respect for all life – human and animal. But the mainstream acts of terrorism – they prevent acts of terrorism. Does not a monkey feel media brands her a violent ‘terrorist’. terror in its stereotaxic chair while its brain is being interfered with? Do not Why? Because she’s carried out direct actions in the name of the Animal beagle puppies having their faces punched not feel some degree of fear? Do Liberation Front (ALF) – from rescuing dogs from vivisection labs to using pigs being blowtorched alive in burns experiments not feel terrorised?” incendiary devices to set fire to some meat lorries and a slaughterhouse. The The ALF have never used the kind of indiscriminate bombs utilised by other latter act took place in 1996 and Arnold spent three and a half years in organisations, Arnold adds. -

Signatories 1

SIGNATORIES 1. Prof. Ralph R. ACAMPORA - Associate Professor, Applied Ethics, Researcher Environmental Ethics, Hofstra University. Hempstead, New York, USA. 2. Prof. Hicham-Stéphane AFEISSA - Professeur agrégé de philosophie, 21000 Dijon, France. Auteur du livre : • "La communauté des êtres de nature" (2010). 3. Jessica ALMY - M.S., Juris Doctor, Attorney, Meyer Glitzenstein & Crystal, Washington DC, USA. 4. Prof. Abel ALVES - PhD, Professor, Department of History, Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana, USA. Author: • Brutality and Benevolence: Human Ethology, Culture, and the Birth of Mexico. Greenwood Press. 1996. 5. Prof. Rosalyn M. AMENTA - PhD, Adjunct Professor, Women's Studies, Women's Studies Steering Committee, Southern Connecticut University, New Haven, Connecticut, USA. 6. Dr. Philippe AMON - Psychiatre attaché, Hôpital Fernand Widal - 75010 Paris, France. 7. Prof. Patricia K. ANDERSON - PhD, Associate Professor, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, Western Illinois University. USA. 8. Deborah C. ANDERSON Esq. - Juris Doctor, Criminal Defense, Washington DC, USA. 9. Maryline ANSART - Psychologue clinicienne, Service Médico-Psychologique Régional – 59374 Loos, France. 10. Suzanne ANTOINE - Président de chambre honoraire à la Cour d'Appel de Paris, 75001 Paris, France. 11. Stephanie APPEL - LMSW (Licensed Master Social Worker). Michigan, USA. 12. Ursula ARAGUNDE-KOHL - PsyD, Clinical Psychology, San Juan, Puerto Rico. 13. Gala ARGENT - MA, Legal Publisher, Argent Communications Group. USA. 14. Prof. Arnold ARLUKE - PhD, Professor of Sociology, Research areas: Qualitative Methods, Social Psychology, Human-Animal Relationships, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA. • Founding Co-Editor, Animals, Culture and Society series, Temple University Press (1996 to present) Selected Publications: • Beauty and the Beast: Human-Animal Relations Revealed in Real Photo Postcards, 1905-1935 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2010) with 1 Robert Bogdan • Inside Animal Hoarding: The Barbara Erickson Case Lafayette, IN: Purdue University Press, 2009) with C. -

A Dis-Ability Perspective on the Stigmatization of Dissent: Critical Pedagogy, Critical Criminology, and Critical Animal Studies

Syracuse University SURFACE Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Social Science - Dissertations Affairs 12-2011 A Dis-Ability Perspective on the Stigmatization of Dissent: Critical Pedagogy, Critical Criminology, and Critical Animal Studies Anthony John Nocella Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/socsci_etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Nocella, Anthony John, "A Dis-Ability Perspective on the Stigmatization of Dissent: Critical Pedagogy, Critical Criminology, and Critical Animal Studies" (2011). Social Science - Dissertations. 178. https://surface.syr.edu/socsci_etd/178 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Science - Dissertations by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This intersectional and interdisciplinary social science qualitative dissertation in six chapters is grounded in critical research and theory for the purpose of engaged public service. This project is grounded in three formal disciplines: education, criminology, and peace and conflict studies. Within those three disciplines, this project interweaves newly emerging fields of study together, including critical animal studies, eco-ability, disability studies, environmental justice, transformative justice, green criminology, anarchist studies, and critical criminology, This dissertation adopts three qualitative methodologies; autoethnography, case study, and critical pedagogy. My project uses the animal advocacy movement as its case study. Using a critical pedagogy methodology, I explored why and how activists respond to the stigmatization of being labeled as or associated with terrorists, a process I refer to as ―terrorization.‖ Chapter One is an introduction to global ecological conditions and post-September 11, 2001 US political repressive conditions toward environmental and animal advocates.