Computing Ethics: the Case for Codes of Ethics and Privacy Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walmart Canada's

Walmart Canada’s Corporate Social Responsibility Report Environment People Ethical Sourcing Community Published September 2011 Introduction Corporate Social Responsibility Report Published September 2011 Message from the President and CEO Welcome to our latest CSR Report. This year’s theme is collaboration – it’s about working with our corporate peers, stakeholders, and even retail competitors to pursue the solutions to challenges which concern us all. We see this report as a powerful tool for corporate good. Our size gives us considerable influence and with it comes considerable responsibility – a role we embrace in order to help Canadians save money and live better. Our goal is to present an open look into the impact of our operations in Canada over the past year. This latest report frames our diverse activities into four broad categories of CSR: Environment, People, Ethical Sourcing and Community. In each area, we highlight our efforts and actions, both large and small – and summarize our current programs and challenges while outlining plans to keep improving in the future. Now ready to share this report with stakeholders, we are tremendously proud of the progress to date but equally aware of how much is still left to do. In the spirit of collaboration that permeates this report, I welcome your feedback to help us better pursue and attain our goals. David Cheesewright President and CEO, Walmart Canada What to look for in our 2011 CSR Report: Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) .........................................................................................................................3 -

Symbol Company Market Maker Market Maker Type Effective Date ACB AURORA CANNABIS INC. Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 ASO AVESORO RESOURCES INC

Symbol Company Market Maker Market Maker Type Effective Date ACB AURORA CANNABIS INC. Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 ASO AVESORO RESOURCES INC. J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 CNL CONTINENTAL GOLD INC. J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 ECN ECN CAPITAL CORP. Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 FF FIRST MINING FINANCE CORP. Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 GCM GRAN COLOMBIA GOLD CORP. J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 LAC LITHIUM AMERICAS CORP. J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 LUC LUCARA DIAMOND CORP. J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 NYX NYX GAMING GROUP LIMITED Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 SWY STORNOWAY DIAMOND CORPORATION J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 USA AMERICAS SILVER CORPORATION J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 WEED CANOPY GROWTH CORPORATION J Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 XRE ISHARES S&P/TSX CAPPED REIT INDEX ETF UN Canaccord Genuity Corp. (#033) Full 12/13/2016 CCX CANADIAN CRUDE OIL INDEX ETF CL 'A' UN CIBC World Markets Inc. (#079) Full 6/13/2017 CGL ISHARES GOLD BULLION ETF HEDGED UNITS CIBC World Markets Inc. (#079) Full 6/13/2017 CIC FIRST ASSET CANBANC INCOME CLASS ETF CIBC World Markets Inc. (#079) Full 6/13/2017 CMR ISHARES PREMIUM MONEY MARKET ETF UNITS CIBC World Markets Inc. (#079) Full 6/13/2017 DXM 1ST ASST MORNSTAR CDA DIV TARGET 30IDX ETF UN CIBC World Markets Inc. -

OSC Bulletin

The Ontario Securities Commission OSC Bulletin September 15, 2016 Volume 39, Issue 37 (2016), 39 OSCB The Ontario Securities Commission administers the Securities Act of Ontario (R.S.O. 1990, c. S.5) and the Commodity Futures Act of Ontario (R.S.O. 1990, c. C.20) The Ontario Securities Commission Published under the authority of the Commission by: Cadillac Fairview Tower Thomson Reuters 22nd Floor, Box 55 One Corporate Plaza 20 Queen Street West 2075 Kennedy Road Toronto, Ontario Toronto, Ontario M5H 3S8 M1T 3V4 416-593-8314 or Toll Free 1-877-785-1555 416-609-3800 or 1-800-387-5164 Contact Centre – Inquiries, Complaints: Fax: 416-593-8122 TTY: 1-866-827-1295 Office of the Secretary: Fax: 416-593-2318 The OSC Bulletin is published weekly by Thomson Reuters Canada, under the authority of the Ontario Securities Commission. Subscriptions to the print Bulletin are available from Thomson Reuters Canada at the price of $868 per year. The eTable of Contents is available from $148 to $155. The CD-ROM is available from $1392 to $1489 and $314 to $336 for additional disks. Subscription prices include first class postage to Canadian addresses. Outside Canada, the following shipping costs apply on a current subscription: 440 grams US – $5.41 Foreign – $18.50 860 grams US – $6.61 Foreign – $10.60 1140 grams US – $7.64 Foreign – $14.70 Single issues of the printed Bulletin are available at $20 per copy as long as supplies are available. Thomson Reuters Canada also offers every issue of the Bulletin, from 1994 onwards, fully searchable on SecuritiesSource™, Canada’s pre-eminent web-based securities resource. -

Climate-Friendly Hydrogen Fuel: a Comparison of the Life-Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Selected Fuel Cell Vehicle Hydrogen Production Systems

Climate-Friendly Hydrogen Fuel: A Comparison of the Life-cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Selected Fuel Cell Vehicle Hydrogen Production Systems prepared by with support from The Pembina Institute The David Suzuki Foundation Climate-Friendly Hydrogen Fuel: A Comparison of the Life-cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Selected Fuel Cell Vehicle Hydrogen Production Systems March 2000 prepared by The Pembina Institute for Appropriate Development with support from The David Suzuki Foundation About the Pembina Institute The Pembina Institute is an independent, citizen-based environmental think-tank specializing in the fields of energy-environment, climate change and environmental economics. The Institute engages in environmental education, policy research and analysis, community sustainable energy development and corporate environmental management services to advance environmental protection, resource conservation, and environmentally sound and sustainable resource management. Incorporated in 1985, the Institute’s head office is in Drayton Valley, Alberta with additional offices in Ottawa and Calgary and research associates in Edmonton, Vancouver Island and other locations across Canada. For more information on the Institute’s work, please visit our website at www.pembina.org, or contact: The Pembina Institute Box 7558 Drayton Valley, AB T7A 1S7 tel: 780-542-6272 fax: 780-542-6464 e-mail: [email protected] About the David Suzuki Foundation The David Suzuki Foundation is a federally registered Canadian charity that explores human impacts on the environment, with an emphasis on finding solutions. We do this through research, application, education and advocacy. The Foundation was established in 1990 to find and communicate ways in which we can achieve a balance between social, economic and ecological needs. -

This Information Is Provided for Information Purposes Only. Neither

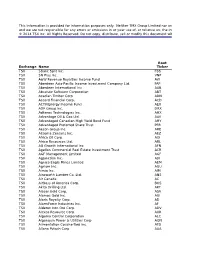

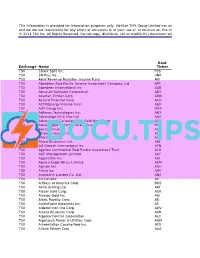

This information is provided for information purposes only. Neither TMX Group Limited nor any of its affiliated companies represents, warrants or guarantees the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this document and we are not responsible for any errors or omissions in or your use of, or reliance on, the information provided. © 2014 TSX Inc. All Rights Reserved. Do not copy, distribute, sell or modify this document without TSX Inc.'s prior written consent. Root Exchange Name Ticker TSX 5Banc Split Inc. FBS TSX 5N Plus Inc. VNP TSX A&W Revenue Royalties Income Fund AW TSX Aberdeen Asia-Pacific Income Investment Company Ltd. FAP TSX Aberdeen International Inc. AAB TSX Absolute Software Corporation ABT TSX Acadian Timber Corp ADN TSX Accord Financial Corp. ACD TSX ACTIVEnergy Income Fund AEU TSX ADF Group Inc. DRX TSX Adherex Technologies Inc. AHX TSX Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd. AAV TSX Advantaged Canadian High Yield Bond Fund AHY TSX Advantaged Preferred Share Trust PFR TSX Aecon Group Inc. ARE TSX AEterna Zentaris Inc. AEZ TSX Africa Oil Corp. AOI TSX Africo Resources Ltd. ARL TSX AG Growth International Inc AFN TSX Agellan Commercial Real Estate Investment Trust ACR TSX AGF Management Limited AGF TSX AgJunction Inc. AJX TSX Agnico Eagle Mines Limited AEM TSX Agrium Inc. AGU TSX Aimia Inc. AIM TSX Ainsworth Lumber Co. Ltd. ANS TSX Air Canada AC TSX AirBoss of America Corp. BOS TSX Akita Drilling Ltd. AKT TSX Alacer Gold Corp. ASR TSX Alamos Gold Inc. AGI TSX Alaris Royalty Corp. AD TSX AlarmForce Industries Inc. AF TSX Alderon Iron Ore Corp. -

Radical Technology Development by Incumbent Firms Daimler's Efforts to Develop Fuel Cell Technology in Historical Perspective

To be presented at the 10th international conference of the Greening of Industry Network June 23-26, Göteborg, Sweden Radical Technology Development by Incumbent Firms Daimler's efforts to develop Fuel Cell technology in historical perspective A paper for: "Corporate Social Responsibility - Governance for Sustainability" 10th International Conference of the Greening of Industry Network June 23-26, 2002 in Göteborg, Sweden Abstract This paper discusses how an established industry as the automotive industry has reacted to the emergence of a radical technology, the fuel cell, with opportunities to answer several environmental concerns. Given that established firms (incumbents) are likely to respond conservative to radical technologies, the automotive industry forms an outstanding case given the large investments it has spent on developing fuel cell vehicles. In this paper a detailed look is taken at one car manufacturer, which was the first to commit serious resources to FC technology: DaimlerBenz/Chrysler. The development of the FC program will be discussed historically in four periods, each distinct with respect to the position and viability of fuel cell vehicles (FCV). The paper draws conclusions concerning the R&D process of technology diffusion within Daimler, the identification of milestones, and assessment of driving forces. It is concluded that Daimler’s activities form a serious ambition to bring FCV to commercial production. Broad environmental concerns are the most important driver for this ambition, together with remarkable technical -

Women in Leadership at S&P/Tsx Companies

WOMEN IN LEADERSHIP AT S&P/TSX COMPANIES Women in Leadership at WOMEN’S S&P/TSX Companies ECONOMIC Welcome to the first Progress Report of Women on Boards and Executive PARTICIPATION Teams for the companies in the S&P/TSX Composite Index, the headline AND LEADERSHIP index for the Canadian equity market. This report is a collaboration between Catalyst, a global nonprofit working with many of the world’s leading ARE ESSENTIAL TO companies to help build workplaces that work for women, and the 30% Club DRIVING BUSINESS Canada, the global campaign that encourages greater representation of PERFORMANCE women on boards and executive teams. AND ACHIEVING Women’s economic participation and leadership are essential to driving GENDER BALANCE business performance, and achieving gender balance on corporate boards ON CORPORATE and among executive ranks has become an economic imperative. As in all business ventures, a numeric goal provides real impetus for change, and our BOARDS collective goal is for 30% of board seats and C-Suites to be held by women by 2022. This report offers a snapshot of progress for Canada’s largest public companies from 2015 to 2019, using the S&P/TSX Composite Index, widely viewed as a barometer of the Canadian economy. All data was supplied by MarketIntelWorks, a data research and analytics firm with a focus on gender diversity, and is based on a review of 234 S&P/TSX Composite Index companies as of December 31, 2019. The report also provides a comparative perspective on progress for companies listed on the S&P/TSX Composite Index versus all disclosing companies on the TSX itself, signalling the amount of work that still needs to be done. -

The Heralds of Hydrogen: the Economicfc Heading Sectors That Heading Are Driving the Hydrogen Economyfc Subheading in Subheading Europe

January 2021 The Heralds of Hydrogen: The economicFC Heading sectors that Heading are driving the hydrogen economyFC Subheading in Subheading Europe I. Introduction The 2019 International Energy Agency (IEA) report on the future of hydrogen highlighted the renewed interest in hydrogen as a potential pathway to a zero-carbon future.1 Since then, many new projects have started and many investment programmes reaching into the billions of euros have been announced, such as the earmarked fund of €9 billion for hydrogen as part of the COVID-19 recovery effort by the German government.2 Yet, uncertainty remains about the precise role of hydrogen in European visions of the energy transition. This raises questions about the support base of the hydrogen economy in Europe. What prompts companies as diverse as for instance Airbus, BP, Enagás, Fincantieri, Linde, Siemens, Škoda, SNCF, and Thyssenkrupp to become members of hydrogen associations? Which economic sectors stand out among supporters of the hydrogen transition? What is the role of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)? These are all relevant questions. The momentum for hydrogen comes at a time when policymakers at the subnational, national and supranational level are faced with the task of reviving their economies in response to the COVID-19 crisis. The European Commission revealed its official hydrogen strategy in July 2020.3 Hydrogen is supposed to become one of the key pillars of the European Green Deal, announced just before the COVID-19 crisis started. Many national policymakers are working on hydrogen too, with recent strategies published in France and Germany, for example. -

Lumina Gold Corp (TSXV: LUM) - Initiating Coverage: Ross Beaty Backed 8.5 Moz Gold Project in Ecuador

Siddharth Rajeev, B.Tech, MBA, CFA May 22, 2019 Lumina Gold Corp (TSXV: LUM) - Initiating Coverage: Ross Beaty Backed 8.5 Moz Gold Project in Ecuador Sector/Industry: Junior Resource www. luminagold.com Market Data (as of May 22, 2019) Investment Highlights Current Price C$0.57 Lumina Gold Corp. (“LUM”, “company”) is advancing its 100% owned Fair Value C$0.93 Cangrejos project in Ecuador, with an inferred resource estimate of 8.5 Moz Rating* BUY gold (0.65 gpt) and 1.03 Blbs copper (0.11%) - making Cangrejos one of the Risk* 5 largest undeveloped gold deposits held by a junior globally . A 2018 Preliminary Economic Assessment (“PEA”) showed an After Tax – 52 Week Range C$0.46 – C$0.82 Net Present Value (“AT-NPV) at 5% of $920 million at $1,300 per oz gold, Shares O/S 309,529,893 and $528 million at $1,170 per oz gold. The current Enterprise Value (“EV”) Market Cap C$ 176.43 mm of Lumina is just C$166 million. Current Yield N/A The total initial CAPEX has been estimated at approximately $831 million, P/E (forward) N/A and a very low life-of-mine (“LOM”) cash cost of $523 per oz. P/B 7.6 x We believe that, Cangrejos, with a potential to produce over 300 Koz YoY Return -26.0 % per year gold, and CAPEX under $1 billion, will be attractive for YoY TSXV -22.5 % acquirers. *see back of report for rating and risk definitions. Recent tax reforms in Ecuador, and several other initiatives taken by the * All figures in US$ unless otherwise specified. -

Top News Before the Bell Stocks to Watch

TOP NEWS • Barrick adj. profit jumps on higher prices, trims gold 2020 output Barrick Gold reported a nearly 55% rise in quarterly adjusted profit, benefiting from a surge in gold prices fueled by concerns over global economic growth. • Shopify posts surprise adjusted profit as lockdowns drive merchants online Shopify posted a surprise adjusted profit for the first quarter and beat revenue estimates as more users visited its platform after lockdowns led merchants to move their businesses online. • CVS Health first-quarter profit beats on COVID-19 stockpiling CVS Health posted first-quarter profit above Wall Street estimates, as its pharmacy benefits management business and its drugstores benefited from customers stockpiling medicines due to COVID-19 lockdowns. • AstraZeneca diabetes drug gets U.S. nod to treat heart failure AstraZeneca's diabetes drug Farxiga has become the first in its class to win U.S. approval as a treatment for heart failure, opening up a major new market opportunity outside of the medicine's established field. • China says tariffs should not be used as a weapon after U.S. threats China said tariffs should not be used as a weapon after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to impose more of them in retaliation for China's handling of the novel coronavirus. BEFORE THE BELL Canada’s main stock index futures rose as oil prices jumped on hopes for a recovery in demand. U.S. stock index futures advanced, supported by easing of coronavirus-driven restrictions by many countries. Most European indexes gained on a jump in healthcare stocks. China shares ended higher as trading resumed after a week-long holiday. -

International Smallcap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017

International SmallCap Separate Account As of July 31, 2017 SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS MARKET % OF SECURITY SHARES VALUE ASSETS AUSTRALIA INVESTA OFFICE FUND 2,473,742 $ 8,969,266 0.47% DOWNER EDI LTD 1,537,965 $ 7,812,219 0.41% ALUMINA LTD 4,980,762 $ 7,549,549 0.39% BLUESCOPE STEEL LTD 677,708 $ 7,124,620 0.37% SEVEN GROUP HOLDINGS LTD 681,258 $ 6,506,423 0.34% NORTHERN STAR RESOURCES LTD 995,867 $ 3,520,779 0.18% DOWNER EDI LTD 119,088 $ 604,917 0.03% TABCORP HOLDINGS LTD 162,980 $ 543,462 0.03% CENTAMIN EGYPT LTD 240,680 $ 527,481 0.03% ORORA LTD 234,345 $ 516,380 0.03% ANSELL LTD 28,800 $ 504,978 0.03% ILUKA RESOURCES LTD 67,000 $ 482,693 0.03% NIB HOLDINGS LTD 99,941 $ 458,176 0.02% JB HI-FI LTD 21,914 $ 454,940 0.02% SPARK INFRASTRUCTURE GROUP 214,049 $ 427,642 0.02% SIMS METAL MANAGEMENT LTD 33,123 $ 410,590 0.02% DULUXGROUP LTD 77,229 $ 406,376 0.02% PRIMARY HEALTH CARE LTD 148,843 $ 402,474 0.02% METCASH LTD 191,136 $ 399,917 0.02% IOOF HOLDINGS LTD 48,732 $ 390,666 0.02% OZ MINERALS LTD 57,242 $ 381,763 0.02% WORLEYPARSON LTD 39,819 $ 375,028 0.02% LINK ADMINISTRATION HOLDINGS 60,870 $ 374,480 0.02% CARSALES.COM AU LTD 37,481 $ 369,611 0.02% ADELAIDE BRIGHTON LTD 80,460 $ 361,322 0.02% IRESS LIMITED 33,454 $ 344,683 0.02% QUBE HOLDINGS LTD 152,619 $ 323,777 0.02% GRAINCORP LTD 45,577 $ 317,565 0.02% Not FDIC or NCUA Insured PQ 1041 May Lose Value, Not a Deposit, No Bank or Credit Union Guarantee 07-17 Not Insured by any Federal Government Agency Informational data only. -

Tsx Tsxv Issuers

This information is provided for information purposes only. Neither TMX Group Limited nor an and we are not responsible for any errors or omissions in or your use of, or reliance on, the inf © 2014 TSX Inc. All Rights Reserved. Do not copy, distribute, sell or modify this document wit Root Exchange Name Ticker TSX 5Banc Split Inc. FBS TSX 5N Plus Inc. VNP TSX A&W Revenue Royalties Income Fund AW TSX Aberdeen Asia-Pacific Income Investment Company Ltd. FAP TSX Aberdeen International Inc. AAB TSX Absolute Software Corporation ABT TSX Acadian Timber Corp ADN TSX Accord Financial Corp. ACD TSX ACTIVEnergy Income Fund AEU TSX ADF Group Inc. DRX TSX Adherex Technologies Inc. AHX TSX Advantage Oil & Gas Ltd. AAV TSX Advantaged Canadian High Yield Bond Fund AHY TSX Advantaged Preferred Share Trust PFR TSX Aecon Group Inc. ARE TSX AEterna Zentaris Inc. AEZ TSX Africa Oil Corp. AOI TSX Africo Resources Ltd. ARL TSX AG Growth International Inc AFN TSX Agellan Commercial Real Estate Investment Trust ACR TSX AGF Management Limited AGF TSX AgJunction Inc. AJX TSX Agnico Eagle Mines Limited AEM TSX Agrium Inc. AGU TSX Aimia Inc. AIM TSX Ainsworth Lumber Co. Ltd. ANS TSX Air Canada AC TSX AirBoss of America Corp. BOS TSX Akita Drilling Ltd. AKT TSX Alacer Gold Corp. ASR TSX Alamos Gold Inc. AGI TSX Alaris Royalty Corp. AD TSX AlarmForce Industries Inc. AF TSX Alderon Iron Ore Corp. ADV TSX Alexco Resource Corp. AXR TSX Algoma Central Corporation ALC TSX Algonquin Power & Utilities Corp AQN TSX Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc.