Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analyse D'œuvres Du Style Artistique Woodland

TRACES DE PEINTURE ARTIDAVI_VF1_Fiche1 Analyse d’œuvres du style artistique Woodland Norval Morrisseau est considéré comme le père du style artistique Woodland. Au cours des années 1970, il s’est affilié à une coopérative d’artistes, desquels certains ont adopté des aspects de ce langage artistique du style Woodland. Par la suite, il y a eu une relève formée d’une nouvelle génération de peintres qui ont trouvé leur inspiration dans ce style, et ce courant se poursuit encore aujourd’hui. Dans cet exercice, tu exploreras des œuvres de ces deux groupes d’artistes : ceux qui étaient à l’origine, et ceux de la relève. Citation de Daphne Odjig : « Nous sommes un peuple vivant et une culture vivante. Je suis convaincue que notre destin est de progresser, d’expérimenter et de développer de nouveaux modes d’expression, comme le font tous les peuples. Je n’ai pas l’intention de rester figée dans le passé. Je n’suis pas une pièce de musée. » Source : Les dessins et peintures de Daphne Odjig : Une exposition rétrospective, Bonnie Devine, Robert Houle et Duke Redbird, 2007. Consigne Tu analyseras deux œuvres, une de chaque groupe. Les œuvres du premier groupe sont celles d’artistes qui ont côtoyé Norval Morrisseau et comme lui, ont adopté un langage artistique similaire. Leurs couleurs plutôt ternes avec l’ocre très présent rappellent celles des pictogrammes et peintures rupestres sur les rochers dans la région des Grands Lacs où ce style est né. Bien que ces œuvres présentent des ressemblances, le style de plusieurs de ces artistes se transformera dans une forme personnelle, surtout à partir des années 1980, quand on verra émerger l’usage de couleurs éclatantes. -

Knowledge Organiser: How Do Artists Represent Their Environment

Knowledge Organiser: How do Artists represent their environment through painting? Timeline of key events 1972 – Three First Nations artists did a joint exhibition in Winnipeg 1973 – Following the success of the exhibition, three artists plus four more, created Indian Group Of Seven to represent Indian art and give it value and recognition. 1975 – Group disbanded Key Information Artists choose to work in a particular medium and style. They represent the world as they see it. Key Places Winnipeg, Manitoba, Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta Key Figures Daphne Odjig 1919 – 2016 Woodland style, Ontario; moved to British Columbia Alex Janvier 1935 – present Abstract, represent hide-painting, quill work and bead work; Alberta Jackson Beardy 1944 - 1984, Scenes from Ojibwe and Cree oral traditions, focusing on relationships between humans and nature. Manitoba. Eddy Cobiness 1933 – 1996 Life outdoors and nature; born USA moved to winnipeg Norval Morrisseau 1931 – 2007 Woodland stlye; Ontario, also known as Copper Thunderbird Carl Ray 1943 – 1978 Woodland style, electrifying colour (founder member); Ontario Joseph Sanchez 1948 – present Spritual Surrealist; Born USA moved to Manitoba Christi Belcourt 1966 – present Metis visual artist, often paints with dots in the style of Indian beading – Natural World; Ontario Key Skills Drawing and designing: Research First Nations artists. Identify which provinces of Canada they come from. Compare and contrast the works of the different artists. Take inspiration from the seven artists to plan an independent piece of art based on the relevant artist: • Give details (including own sketches) about the style of some notable artists, artisans and designers. • type of paint, brush strokes, tools Symbolic representation • Create original pieces that show a range of influences and styles based on the Indian Group of Seven and their work. -

Windspeaker February 1996

--.11., QUOTABLE QUOTE "National Chief Mercredi's actions and statements are an insult to the chiefs." - Manitoba Grand Chief Phil Fontaine '2 00 where applicable PUBLICATION MAIL REGISTRATION k2177 13 No. IO FEBRUARY 1996 Canada's National Aboriginal News Publication Volume POSTAGE PAID AT EDMONTON Thumbs up for treaties VANCOUVER Negotiation is the only acceptable and civilized way for Native people and the government to deal with the complex issues of Abo- riginal title and rights in the province of British Columbia, said Chief Joe Mathias. He was responding to a new study, conducted by ARA Con- sulting Group of Vancouver, which found land claim treaties have a positive effect in regards to economic opportunity, community development and improved relations between Aboriginal and non- Aboriginal people. "The strength of this report is that it provides an independent and balanced perspective of the issues, challenges and opportuni- ties of treaty- making," said Mathias. "It is a critically important and timely document, one we expect will generate constructive public debate in the months ahead." The study found that modern day treaties have not caused the kind of disruption and disharmony their critics contend they do, but neither do they offer instant solutions. A summary report pre- pared by Ken Coates of the University of Northern British Colum- bia said the resolution of long- standing disagreements, through negotiation rather than through legal or politically imposed con- ditions, will liberate people from the contentious and difficult de- bates of the past. "These often heated discussions - about colonialism, disloca- tion, sovereignty, ownership, and the legitimacy of Native land claims - generate a great deal of rhetoric and anger but rarely pro- vide lasting solutions," concludes the summary. -

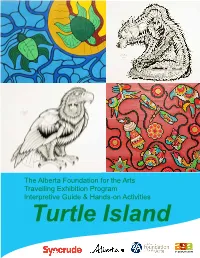

Turtle Island Education Guide

The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program Interpretive Guide & Hands-on Activities Turtle Island The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program The Interpretive Guide The Art Gallery of Alberta is pleased to present your community with a selection from its Travelling Exhibition Program. This is one of several exhibitions distributed by The Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program. This Interpretive Guide has been specifically designed to complement the exhibition you are now hosting. The suggested topics for discussion and accompanying activities can act as a guide to increase your viewers’ enjoyment and to assist you in developing programs to complement the exhibition. Questions and activities have been included at both elementary and advanced levels for younger and older visitors. At the Elementary School Level the Alberta Art Curriculum includes four components to provide students with a variety of experiences. These are: Reflection: Responses to visual forms in nature, designed objects and artworks Depiction: Development of imagery based on notions of realism Composition: Organization of images and their qualities in the creation of visual art Expression: Use of art materials as a vehicle for expressing statements The Secondary Level focuses on three major components of visual learning. These are: Drawings: Examining the ways we record visual information and discoveries Encounters: Meeting and responding to visual imagery Composition: Analyzing the ways images are put together to create meaning The activities in the Interpretive Guide address one or more of the above components and are generally suited for adaptation to a range of grade levels. -

Witnesswitness

Title Page WitnessWitness Edited by Bonnie Devine Selected Proceedings of Witness A Symposium on the Woodland School of Painters Sudbury Ontario, October 12, 13, 14, 2007 Edited by Bonnie Devine A joint publication by the Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness Book design Red Willow Designs Red Willow Designs Copyright © 2009 Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness www.aboriginalcuratorialcollective.org All rights reserved under international copyright conventions. Published in conjunction with the symposium of the same title, October 12 through 15, 2007. Photographs have been provided by the owners or custodians of the works reproduced. Photographs of the event provided by Paul Gardner, Margo Little and Wanda Nanibush. For Tom Peltier, Jomin The Aboriginal Curatorial Collective and Witness gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council Cover: Red Road Rebecca Belmore October 12 2007 Image: Paul Gardner Red Willow Designs Aboriginal Curatorial Collective / Witness iii Acknowledgements This symposium would not have been possible without the tremendous effort and support of the Art Gallery of Sudbury. Celeste Scopelites championed the proposal to include a symposium as a component of the Daphne Odjig retrospective exhibition and it was her determination and vision that sustained the project through many months of preparation. Under her leadership the gallery staff provided superb administrative assistance in handling the myriad details an undertaking such as this requires. My thanks in particular to Krysta Telenko, Nancy Gareh- Coulombe, Krista Young, Mary Lou Thomson and Greg Baiden, chair of the Art Gallery of Sudbury board of directors, for their enthusiasm and support. -

Breaking Barriers the Artist Inside

Interpretive Guide & Hands-on Activities The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program Breaking Barriers The Artist Inside youraga.ca The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program The Interpretive Guide The Art Gallery of Alberta is pleased to present your community with a selection from its Travelling Exhibition Program. This is one of several exhibitions distributed by The Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program. This Interpretive Guide has been specifically designed to complement the exhibition you are now hosting. The suggested topics for discussion and accompanying activities can act as a guide to increase your viewers’ enjoyment and to assist you in developing programs to complement the exhibition. Questions and activities have been included at both elementary and advanced levels for younger and older visitors. At the Elementary School Level the Alberta Art Curriculum includes four components to provide students with a variety of experiences. These are: Reflection: Responses to visual forms in nature, designed objects and artworks Depiction: Development of imagery based on notions of realism Composition: Organization of images and their qualities in the creation of visual art Expression: Use of art materials as a vehicle for expressing statements The Secondary Level focuses on three major components of visual learning. These are: Drawings: Examining the ways we record visual information and discoveries Encounters: Meeting and responding to visual imagery Composition: Analyzing the ways images are put together to create meaning The activities in the Interpretive Guide address one or more of the above components and are generally suited for adaptation to a range of grade levels. -

Woodlands the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program the Interpretive Guide

Interpretive Guide & Hands-on Activities The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program Woodlands The Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program The Interpretive Guide The Art Gallery of Alberta is pleased to present your community with a selection from its Travelling Exhibition Program. This is one of several exhibitions distributed by The Art Gallery of Alberta as part of the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Travelling Exhibition Program. This Interpretive Guide has been specifically designed to complement the exhibition you are now hosting. The suggested topics for discussion and accompanying activities can act as a guide to increase your viewers’ enjoyment and to assist you in developing programs to complement the exhibition. Questions and activities have been included at both elementary and advanced levels for younger and older visitors. At the Elementary School Level the Alberta Art Curriculum includes four components to provide students with a variety of experiences. These are: Reflection: Responses to visual forms in nature, designed objects and artworks Depiction: Development of imagery based on notions of realism Composition: Organization of images and their qualities in the creation of visual art Expression: Use of art materials as a vehicle for expressing statements The Secondary Level focuses on three major components of visual learning. These are: Drawings: Examining the ways we record visual information and discoveries Encounters: Meeting and responding to visual imagery Composition: Analyzing the ways images are put together to create meaning The activities in the Interpretive Guide address one or more of the above components and are generally suited for adaptation to a range of grade levels. -

August 2018 Preview-Art.Com

GUIDE TO GALLERIES + MUSEUMS ALBERTA BRITISH COLUMBIA OREGON WASHINGTON June - August 2018 preview-art.com 2018_JJA_document_Final.indd 1 2018-05-23 9:37 AM Appearance New Works by Jianjun An August 20 – Sept 7, 2018 Opening Reception: Aug 23rd, 18:00 pm Panel Discussion: Aug 23rd, 19:00 pm Pendulum Gallery HSBC Building Atrium, 885 West Georgia, Vancouver, BC V6C 3E8 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday: 9:00am–5:00pm Thursday, Friday: 9:00am–9:00pm Saturday: 9:00am–5:00pm Sundays and Stat Holidays: Closed e: [email protected] www.jianjunan.com T: 778.8952283 778.8595298 Blue Heron & Fisherman’s Wharf diptych 96” x 120” Presented by : New Primary Color Art Foundation R Space Art Development Foundation bscottfinearts.ca Advised by Shengtian Zheng | Liu, Yi 2227 Granville Street, Vancouver BC Curated by Sen Wong Co-ordinated by Li Feng 8269 North Island Highway, Black Creek 2018_JJA_document_Tue_1115.indd 2 2018-05-22 9:02 PM Appearance New Works by Jianjun An August 20 – Sept 7, 2018 Opening Reception: Aug 23rd, 18:00 pm Panel Discussion: Aug 23rd, 19:00 pm Pendulum Gallery HSBC Building Atrium, 885 West Georgia, Vancouver, BC V6C 3E8 Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday: 9:00am–5:00pm Thursday, Friday: 9:00am–9:00pm Saturday: 9:00am–5:00pm Sundays and Stat Holidays: Closed e: [email protected] www.jianjunan.com T: 778.8952283 778.8595298 Blue Heron & Fisherman’s Wharf diptych 96” x 120” Presented by : New Primary Color Art Foundation R Space Art Development Foundation bscottfinearts.ca Advised by Shengtian Zheng | Liu, Yi 2227 Granville Street, Vancouver BC Curated by Sen Wong Co-ordinated by Li Feng 8269 North Island Highway, Black Creek BC BrianScottAd.indd2018_JJA_document_Final.indd 1 3 2018-05-23 3:323:34 PM Installation Storage Shipping Transport Framing Poly Culture Art Center 100 - 905 West Pender Street Vancouver, BC V6C 1L6 展览地点 温哥华保利艺术馆 主办单位 保利文化集团股份有限公司 承办单位 保利文化北美投资有限公司 北京保利艺术中心有限公司 Venue Providing expert Poly Culture Art Center handling of your fine art Organizer Poly Culture Group for over thirty years. -

LAND & INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS Through the Art of NORVAL

TEACHER RESOURCE GUIDE FOR GRADES 9–12 LEARN ABOUT LAND & INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS through the art of NORVAL MORRISSEAU Click the right corner to LAND AND INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS NORVAL MORRISSEAU through the art of return to table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1 PAGE 2 PAGE 3 RESOURCE WHO WAS NORVAL TIMELINE OF OVERVIEW MORRISSEAU? HISTORICAL EVENTS AND ARTIST’S LIFE PAGE 4 PAGE 8 PAGE 11 LEARNING CULMINATING HOW NORVAL ACTIVITIES TASK MORRISSEAU MADE ART: STYLE & TECHNIQUE PAGE 12 READ ONLINE DOWNLOAD ADDITIONAL NORVAL MORRISSEAU: NORVAL MORRISSEAU RESOURCES LIFE & WORK IMAGE FILE BY CARMEN ROBERTSON EDUCATIONAL RESOURCE LAND AND INDIGENOUS WORLDVIEWS through the art of NORVAL MORRISSEAU RESOURCE OVERVIEW This teacher resource guide has been designed to complement the Art Canada Institute online art book Norval Morrisseau: Life & Work by Carmen Robertson. The artworks within this guide and images required for the learning activities and culminating task can be found in the Norval Morrisseau Image File provided. Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007) is considered by many to be the Mishomis, or grandfather, of contemporary Indigenous art in Canada. He is known for creating a distinctive style of painting that came to be known as the Woodland School, and for addressing a wide range of themes in his work, from spiritual beliefs to colonial history. Throughout his career, he explored ways of thinking about the land, and many of his most famous paintings emphasize the idea of land as a relation; Morrisseau believed that people live in relationship with animals, plants, the earth, and the spiritual world, a conviction shared by many Indigenous communities. -

Mcmichael Magazine ISSN 2368-1144 from the Mcmichael Canadian Art Collection of Contemporary Northwest Coast Art Transforming Spirit: the Cameron/Bredt Collection

ISSUE THREE | SUMMER & FALL 2015 2015 ISSUE THREE | SUMMER & FALL McMichael Magazine ISSN 2368-1144 ISSN From the McMichael Canadian Art Collection CAN $4.95 of Contemporary Northwest Coast Art Coast Northwest Contemporary of Collection Spirit: The Cameron/Bredt Transforming 7: Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. Frank (Franz) Johnston Thom Sokoloski McMichael Magazine / I Board of Trustees From the Permanent Collection On the Cover Upkar Arora, Chair Joan Bush Don Yeomans (b. 1958), Bear Peter Carayiannis Mask (detail), 2009, red cedar, Tony Carella paint, 99.4 x 61.5 x 31.8 cm, Gift Andrew Dunn Diana Hamilton of Christopher Bredt and Jamie Anita Lapidus Cameron, McMichael Canadian Linda Rodeck Art Collection, 2014.6.49 John Silverthorn Tina Tehranchian Michael Weinberg Diane Wilson Rosemary Zigrossi Ex-officio Victoria Dickenson Executive Director and CEO Guests Meegan Guest, Director-in-Training Jane Knop, Director-in-Training Christopher Henley, Foundation Chair Maurice Cullen (1866–1934), Chutes aux Caron, c. 1928, Geoff Simpson, Volunteer Committee President oil on canvas, 102.3 x 153 cm, Gift of Mrs. Janet Heywood, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, 2003.1 McMichael Canadian Art Foundation Board of Directors Christopher Henley, Chair Victoria Dickenson, President David Melo, Treasurer Upkar Arora Jordan Beallor Isabella Bertani Mark Bursey Doris Chan Susan Hodkinson Iain MacInnes Doug McDonald McMichael Honorary Council The McMichael Vision Harry Angus John Bankes H. Michael Burns To be recognized as an extraordinary Jamie Cameron Robert C. Dowsett Jan Dymond place to visit and explore Canadian culture Dr. Esther Farlinger, O.Ont George Fierheller, C.M. and identity, and the connections between Hon. -

Upcoming Events

Upcoming Events JANUARY Welcome to the January edition of the E-Voice! Check out all the events happening around the province Office Closed Archaeology Centre this month. (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) JANUARY Department of Archaeology & Anthropology Lecture Series 4:30 ‐ 6:00 pm ARTS 102 (9 Campus Drive) Don't forget to sign up or renew your 2019 SAS membership too! You can either give us a call JANUARY Saskatoon (306-664-4124), stop by, fill out the form (PDF) or go online to our website. Remember our student Archaeological Society Monthly Meeting rate is now only $15/year! 7:00 pm Room 132, Archaeology Building We're starting up our Drop-In Tuesdays again this month. Stop by on January 30th from 1:30 - 3:30 pm 55 Campus Drive at the Archaeology Centre to see what we're up to, chat about all things archaeology, and have a JANUARY Drop‐In Tuesdays coffee/tea and some tasty treats! 1:30 ‐ 3:30 pm Archaeology Centre Stay tuned to our website and social media pages for information on archaeological happenings in the (1‐1730 Quebec Avenue) province and across the world. Each week we feature a Saskatchewan archaeological site on our #TBT "Throwback Thursdays" and archaeology and food posts on our #FoodieFridays! About the SAS Office Hours: Monday to Thursday 9:00 am - 4:00 pm The Saskatchewan Archaeological Friday: by appointment only Society (SAS) is an independent, charitable, non-profit organization that was founded in 1963. We are one of the largest, Seasonal Closure: Monday, January 1st, 2019 to Friday, January 4th, 2019 inclusive most active and effective volunteer organizations on the We will reopen for regular office hours on Monday, January 7th, 2019 at 9:00 am. -

Native People of Western Canada Contents

Native People of Western Canada Contents 1 The Ojibwa 1 1.1 Ojibwe ................................................. 1 1.1.1 Name ............................................. 1 1.1.2 Language ........................................... 2 1.1.3 History ............................................ 2 1.1.4 Culture ............................................ 4 1.1.5 Bands ............................................. 7 1.1.6 Ojibwe people ......................................... 9 1.1.7 Ojibwe treaties ........................................ 11 1.1.8 Gallery ............................................ 11 1.1.9 See also ............................................ 11 1.1.10 References .......................................... 11 1.1.11 Further reading ........................................ 12 1.1.12 External links ......................................... 13 2 The Cree 14 2.1 Cree .................................................. 14 2.1.1 Sub-groups .......................................... 14 2.1.2 Political organization ..................................... 15 2.1.3 Name ............................................. 15 2.1.4 Language ........................................... 15 2.1.5 Identity and ethnicity ..................................... 16 2.1.6 First Nation communities ................................... 17 2.1.7 Ethnobotany ......................................... 17 2.1.8 Notable leaders ........................................ 17 2.1.9 Other notable people ..................................... 20 2.1.10 See also ...........................................