Scotlands Colleges 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Lothian College Board of Governors Tuesday 08 December 2020 at 4.30Pm

West Lothian College Board of Governors Tuesday 08 December 2020 at 4.30pm Agenda Item Paper 1 Welcome and apologies 2 Declarations of Interest 3 Minute of Meeting of 22 September 2020 1 For Approval 4 Matters Arising from Minute of Meeting of 22 September 2 For Approval 2020 Board Business 5 Student Association Report 3 For Information 6 Chief Executive’s Report 4 For Information 7 Regional Chair’s Feedback Verbal 8 Board Development i) Report from Board Secretary – Board Development 5 To Note Committee Business 9 Learning and Teaching Committee i) Update from Chair of the Learning and Teaching 6 For Information Committee from draft minute of 18 November 2020 ii) Curriculum Plan 2020-21 Presentation 10 Finance and General Purposes Committee: i) Update from Chair of the Finance and General Purposes Committee from draft minute of 25 7 For Information November 2020 ii) People Strategy 8 For Approval 11 Audit Committee i) Update from Chair of the Audit Committee from draft 9 For Information minute of 26 November 2020 ii) Annual Report & Financial Statements for 2019-20 10 For Approval iii) Annual Report to the Board of Governors and the 11 To Discuss Auditor General for Scotland 2019-20 iv) Audit Committee’s Report to the Board 12 For Information v) Letter of Representation 13 For Approval vi) Health & Safety Quarterly Report 14 For Information vii) Strategic Risk Register 15 For Information 12 Update from Chair of the Remuneration Committee Verbal 13 Nominations Committee i) Update from Chair of the Nominations Committee 16 For Information from 29 October 2020 ii) Secretary to the Board 17 For Approval 14 Any Other Business 15 Board Development Plan, Review of Meeting, and 18 For Information Supporting Papers 16 Date of Next Meeting: 9 March 2021 at 4.30 p.m. -

College Innovation the Heart of Scotland's Future

FOR SCOTLAND’S COLLEGE SECTOR 2020 THE HEART OF SCOTLAND’S FUTURE An interview with Karen Watt, Chief Executive of the Scottish Funding Council p11 COLLEGE INNOVATION Innovation has never been more important, says City of Glasgow College p12 PROJECT PLASTIC How Dundee and Angus College is tackling the climate emergency head on p30 REACHING NEW HEIGHTS Colleges have a crucial role to play in the new vision for Scotland’s tourism and hospitality sector 11 28 2020 Editor Wendy Grindle [email protected] Assistant Editor Tina Koenig [email protected] Front Cover The cover photo shows Rūta Melvere with her snowboard. She completed the West Highland College UHI Outdoor Leadership NQ and came back to study BA (Hons) Adventure Tourism Management. She has gone on to start her own tourism business. The photo was taken by Simon Erhardt, who CONTENTS studied BA (Hons) Adventure Performance and Coaching at West Highland College UHI and graduated in 2018. 4 ROUND-UP 24 COLLEGE VOICE The latest projects and initiatives The CDN Student of the Year and Colleague of the Year speak to Reach Reach is produced by Connect Publications (Scotland) 9 ADULT LEARNING Limited on behalf of College Development Network Richard Lochhead MSP on a new national strategy 26 DIGITAL COLLEGES A digital learning network has been formed by 11 INTERVIEW Dumfries and Galloway and Borders Colleges Karen Watt, Chief Executive of the Scottish Funding Studio 2001, Mile End Council (SFC), reflects on the role of colleges 12 Seedhill Road 28 INCLUSION Paisley PA1 1JS Fife College -

BOARD of MANAGEMENT Tuesday 19 March 2019 at 5.00Pm, Seminar Room 5, Arbroath Campus

BOARD OF MANAGEMENT Tuesday 19 March 2019 at 5.00pm, Seminar Room 5, Arbroath Campus AGENDA 1. WELCOME 2. APOLOGIES 3. DECLARATION S OF INTEREST 4. ESRC RESEARCH PROJECT – INFORMED Paper A for information CONSENT 5. EDUCATION SCOTLAND QUALITY REPORT Presentation P Connolly FEEDBACK HMIE 6. MINUTE OF LAST MEETING – 11 DECEMBER 2018 Paper B for approval AMc 6.1 Adoption 6.2 Matters Arising 7. STRATEGIC ITEMS 7.1 Strategic Risk Register Paper C for discussion ST 7.2 Good to Great Strategy Project Report Paper D for discussion GR 7.3 Regional Outcome Agreement Final Draft Paper E approval ST 7.4 Future Strategy – Strategic Session Update Paper F for approval GR/SH 7.5 Board Development Sessions Verbal update AMc 8. NATIONAL BARGAINING UPDATE Verbal update GR/ST 9. PRINCIPAL’S REPORT Paper G for information GR 9.1 SFC Strategic Dialogue Verbal update GR/AMc 10. FINANCE ITEMS 10.1 Financial Strategy Paper H for approval CB 10.2 Estates Strategy Paper I for approval CB 11. STUDENTS’ ASSOCIATION REPORT Verbal update DH/RW 12. GOVERNANCE ITEMS 12.1 Board Membership Paper J for information ST 12.2 Governance Update Paper K for information ST 12.3 Board Metrics Paper L for information ST 12.4 2019/2020 Board Meeting Dates Paper M for approval ST 13. MINUTES OF COMMITTEE MEETINGS Paper N for information AMc 13.1 Learning, Teaching & Quality – 13 February 2019 13.2 Audit & Risk – 5 March 2019 13.3 Human Resource & Development – 21 February 2019 13.4 Finance & Property – 22 January 2019 & 12 March 2019 (verbal update) 14. -

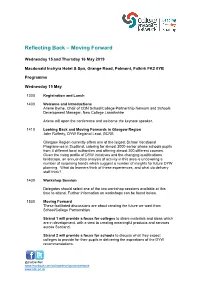

Reflecting Back – Moving Forward

Reflecting Back – Moving Forward Wednesday 15 and Thursday 16 May 2019 Macdonald Inchyra Hotel & Spa, Grange Road, Polmont, Falkirk FK2 0YB Programme Wednesday 15 May 1300 Registration and Lunch 1400 Welcome and Introductions Arlene Byrne, Chair of CDN School/College Partnership Network and Schools Development Manager, New College Lanarkshire Arlene will open the conference and welcome the keynote speaker. 1410 Looking Back and Moving Forwards in Glasgow Region John Rafferty, DYW Regional Lead, GCRB Glasgow Region currently offers one of the largest School Vocational Programmes in Scotland, catering for almost 3000 senior phase schools pupils from 4 different local authorities and offering almost 200 different courses. Given the rising profile of DYW initiatives and the changing qualifications landscape, an annual data analysis of activity in this area is uncovering a number of surprising trends which suggest a number of insights for future DYW planning. What do learners think of these experiences, and what do delivery staff think? 1430 Workshop Session Delegates should select one of the two workshop sessions available at this time to attend. Further information on workshops can be found below. 1530 Moving Forward These facilitated discussions are about creating the future we want from School/College Partnerships Strand 1 will provide a focus for colleges to share materials and ideas which are in development, with a view to creating meaningful products and services across Scotland. Strand 2 will provide a focus for schools to discuss -

Major Players

PUBLIC BODIES CLIMATE CHANGE DUTIES – MAJOR PLAYER ORGANISATIONS Aberdeen City Council Aberdeen City IJB Aberdeenshire Council Aberdeenshire IJB Abertay University Accountant in Bankruptcy Angus Council Angus IJB Argyll and Bute Council Argyll and Bute IJB Audit Scotland Ayrshire College Borders College City of Edinburgh Council City of Glasgow College Clackmannanshire and Stirling IJB Clackmannanshire Council Comhairlie nan Eilean Siar Creative Scotland Disclosure Scotland Dumfries and Galloway College Dumfries and Galloway Council Dumfries and Galloway IJB Dundee and Angus College Dundee City Council Dundee City IJB East Ayrshire Council East Ayrshire IJB East Dunbartonshire Council East Dunbartonshire IJB East Lothian Council Sustainable Scotland Network Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Innovation, High School Yards, Edinburgh, EH1 1LZ 0131 650 5326 ú [email protected] ú www.sustainablescotlandnetwork.org East Lothian IJB East Renfrewshire Council East Renfrewshire IJB Edinburgh College City of Edinburgh IJB Edinburgh Napier University Education Scotland Falkirk Council Falkirk IJB Fife College Fife Council Fife IJB Food Standards Scotland Forth Valley College Glasgow Caledonian University Glasgow City Council Glasgow City IJB Glasgow Clyde College Glasgow Kelvin College Glasgow School of Art Heriot-Watt University The Highland Council Highlands and Islands Enterprise Highlands and Islands Transport Partnership (HITRANS) Historic Environment Scotland Inverclyde Council Inverclyde IJB Inverness College UHI Lews Castle College -

Agenda and Papers Thursday 01 April 2021

Board of Management Meeting Board of Management Date and time Thursday 01 April 2021 at 4.30 p.m. Location VC – Microsoft Teams Board Secretary 25 March 2021 AGENDA Welcome and Apologies Declarations of Interest Presentation by Nicola Quinn, HR Manager on Results of the Staff Survey ITEMS FOR DECISION 1. MINUTES Meeting of the Board of Management – 18 February 2021 2. OUTSTANDING ACTIONS Action List 3. POLICIES FOR APPROVAL • Complaints Policy 4. SCHEDULE OF BOARD AND COMMITTEE MEETINGS – 2021/22 5. OSCR RETURN 6. DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2021-22 7. AUDIT COMMITTEE MATTERS FOR BOARD APPROVAL - CONFIDENTIAL Extension to Internal Auditors Contract ITEMS FOR DISCUSSION 8. SHARED FINANCE SERVICE Report by Director of Finance 9. COVID-19 AND PLANNING FOR 21/22 REPORT • Report by Principal • Additional Facility for Construction Delivery – Lease Approval Page 1 of 2 10. PRINCIPAL’S REPORT Report by Principal 11. HEALTH AND SAFETY POLICY AND STATEMENT ANNUAL REVIEW 12. PARTNERSHIP AND PARTNERSHIP COUNCIL UPDATE Report by Principal 13. DRAFT MINUTES OF MEETINGS OF BOARD COMMITTEES - (CONFIDENTIAL) a) Minutes of HR Committee held on 12 November 2020 b) Minutes of LT&R Committee held on 17 November 2020 c) Minutes of Joint Audit & F&GP Committee held on 27 January 2021 d) Minutes of F&GP Committee held on 27January 2021 e) Minutes of Estates Legacy Committee held on 04 February 2021 f) Minuets of Chairs Committee held on 04 March 2021 g) Minutes of Audit Committee held on 09 March 2021 FOR NOTING 14. UHI COURT – QUARTERLY UPDATE FROM UHI SMT & ACADEMIC PARTNERS a) 01 September 2020 – 30 November 2020 b) 01 December 2020 – 28 February 2021 15. -

Assignation of Argyll College to the Regional Strategic Body for the Highlands and Islands, the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI)

Assignation of Argyll College to the Regional Strategic Body for the Highlands and Islands, the University of the Highlands and Islands (UHI) Consultation Paper May 2018 ASSIGNATION OF ARGYLL COLLEGE TO THE REGIONAL STRATEGIC BODY FOR THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS, THE UNIVERSITY OF THE HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS (UHI) CONSULTATION PAPER SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION 1.1 The college sector was restructured in 2014 to create 13 regions, three of which are served by more than one college. In the three multi-college regions, colleges were assigned to a Regional Strategic Body (RSB). The RSB is responsible for securing provision of fundable further and higher education in its region. 1.2 On 1 August 2014, the University of Highlands and Islands (UHI) became the RSB for the Highlands and Islands, and those colleges in the region that were already fundable bodies listed in schedule 2 to the Further and Higher Education (Scotland) Act 2005 (“the 2005 Act”) – i.e. colleges directly funded by the Scottish Further and Higher Education Funding Council (“the SFC”) – were assigned to UHI. From that date, UHI assumed all of the responsibilities of RSB for the region, other than the direct funding of assigned colleges, responsibility for which was subsequently transferred from the SFC in April 2015. 1.3 Argyll College (“the College”) is located within the Highlands and Islands region and should therefore be assigned to UHI as the RSB to ensure appropriate accountability across the region. However, as the College was not already a fundable body listed in schedule 2 to the 2005 Act, it could only be assigned to UHI if the SFC proposed or approved the assignation. -

Reach Magazine 2021 (Pdf)

FOR SCOTLAND’S COLLEGE SECTOR 2021 PROTECTING OUR PLANET Staff and students from one college have come together to tackle the Climate Emergency p12 WHOLE-COLLEGE WELLBEING Supporting the mental health and wellbeing of the whole college community p46 DIGITAL LEARNING College learning and teaching is embracing digital delivery as never before FOR SCOTLAND’S COLLEGE SECTOR 2021 PROTECTING OUR PLANET Staff and students from one 12 college have come together to tackle the Climate Emergency p12 WHOLE-COLLEGE WELLBEING Supporting the mental health and wellbeing of the whole college community p46 24 DIGITAL LEARNING College learning and teaching is embracing digital delivery as never before 2021 Editor Wendy Grindle [email protected] CONTENTS Assistant Editor Tina Koenig [email protected] 4 ROUND-UP 28 INDUSTRY SPOTLIGHT The latest news from CDN and Scotland’s The college sector will play a critical role in post- Thank you to all contributors and those who college sector Covid recovery by working with employers helped to put this edition of Reach magazine together. 9 STUDENT OF THE YEAR 32 INTERVIEW We speak to Kirstie Ann Duncan, CDN College We speak to Helena Good, Tes FE Teacher Front Cover Awards 2020 Student of the Year of the Year Colleges have embraced digital delivery as never before... read about some of the key 10 NUS PRESIDENT 34 SCOTTISH FUNDING COUNCIL learning on page 16. Matt Crilly makes the case for more student Karen Watt, Chief Executive of the Scottish support Funding Council, looks at the three-phase review of tertiary -

Colleges and Universities Contact Information

Entry to the Creative Industries Colleges and Universities Contact Information The following provides information on colleges and universities where you can study a performing and/or production arts course. All information is divided into college study, university study and subject areas. Please note you can only access the course details if you are connected to the internet. All information and links were correct at the time of production. www.rsamd.ac.uk/academyworks/focuswestChloe Dobson - Entry to the Creative Industries, Widening Access and Participation 0141 270 8319 [email protected] http://www.rcs.ac.uk/about_us/entry-creative-industries/ www.focuswest.org.uk COLLEGES ACTING DANCE Ayrshire College Dundee and Angus College www.ayrshire.ac.uk www.dundeeandangus.ac.uk City of Glasgow College Edinburgh College www.cityofglasgowcollege.ac.uk www.edinburghcollege.ac.uk Dundee and Angus College Glasgow Clyde College www.dundeeandangus.ac.uk www.glasgowclyde.ac.uk Edinburgh College Glasgow Kelvin College www.edinburghcollege.ac.uk www.glasgowkelvin.ac.uk Fife College New College Lanarkshire www.fife.ac.uk www.nclanarkshire.ac.uk Glasgow Clyde College West College Scotland www.glasgowclyde.ac.uk www.westcollegescotland.ac.uk Glasgow Kelvin College www.glasgowkelvin.ac.uk Inverness College www.uhi.ac.uk New College Lanarkshire www.nclanarkshire.ac.uk North East Scotland College www.nescol.ac.uk West College Scotland www.westcollegescotland.ac.uk MUSIC PERFORMANCE RADIO Ayrshire College City of Glasgow College www.ayrshire.ac.uk www.cityofglasgowcollege.ac.uk -

West College Scotland Learning, Teaching and Quality Committee

West College Scotland Learning, Teaching And Quality Committee Wednesday 13th November 2019 in the Cunard Suite, Clydebank Campus Agenda General Business 1. Apologies 2. Declaration of Interests 3. Minutes of the meeting held on 22 May Enclosed Actions from the minutes Enclosed 4. Matters arising from the Minutes (and not otherwise on the agenda) Main Items for Discussion and/or Approval 5. Committee Remit, Membership and Dates of Meetings Paper 5 DM 6. Educational Leadership Team update Paper 6 SG 7. Students Association Update Oral Report VT 8. Education Scotland (standing item) Oral Report CM 9. 2019-20 Enrolment update Paper 9 SG 10. Regional Outcome Agreement Monitoring Paper 10 SG 11. 2020-21 to 2022-23 Regional Outcome Agreement Paper 11 SG 12. Student Survey Paper 12 CM 13. Internal Audit and report on Safeguarding Paper 13 IFS 14. Internal Audit Report – Student Experience Paper 14 IFS 15. Risk Paper 15 SG For information 16. College Leaver Destinations Published Report 17. Quality Standards Committee Minutes 18. Inverclyde Council Report on WCS Provision 19. Any other business Next meeting: 26 February 2020 at the Paisley Campus Drew McGowan Interim Secretary to the Committee LEARNING, TEACHING AND QUALITY COMMITTEE MINUTES: 22 May 2019 Present: Mike Haggerty (in the Chair), Jacqueline Henry, Ruth Binks, Nicole Percival, Danny Walls. Attending: Stephanie Graham (Vice Principal Educational Leadership), Cathy MacNab (Assistant Principal, Performance and Skills), Iain Forster-Smith (Assistant Principal, Student Life and Skills), Gwen McArthur (Secretary to the Committee). Apologies: Liz Connolly, Keith McKellar, David Watson. LM312 WELCOME The Chair welcomed the new member, Ruth Binks, Corporate Director of Education, Communities and Organisational Development, Inverclyde Council to the meeting. -

Sparqs' Student Engagement Awards

sparqs’ Student Engagement Awards 2021 Shortlists Award 1: A student-led initiative in a college Thank you forms: bringing Fife College students and academic staff closer ~ Fife College Students’ Association Muckers Nation – The Students’ Online Equine Community at SRUC ~ Scotland’s Rural College (SRUC) Award 2: A student-led initiative in a university Learner Support for Protected Characteristics Focus Groups ~ Heriot-Watt University School of Life Sciences Academic Events and Social Media ~ University of Dundee Award 3: A students’ association-led initiative in a college Discovering DASA ~ Dundee and Angus College Students’ Association Winter Wonderland 2020 ~ Fife College Students’ Association Class Representative Meetings – Restructure ~ Glasgow Clyde College Students’ Association Award 4: A students’ association-led initiative in a university Collaborative development of ENSA online Programme Rep training ~ Edinburgh Napier Students’ Association Recruiting & Supporting Class Reps in a Remote Working Environment workshop ~ Glasgow Caledonian University Students’ Association Award 5: A partnership initiative in a college Designing with, not for ~ Dundee and Angus College Closing the Gap with 360 approach to feedback ~ New College Lanarkshire and NCL Students’ Association Dive in to an impactful way to embed, diversity, inclusion, values and equality ~ West Lothian College Students’ Association and West Lothian College Award 6: A partnership initiative in a university RGU Welcome: New online support of student orientation, integration, and wellbeing during the Covid-19 pandemic ~ Robert Gordon University and RGU:Union StrathReps: A Student Rep Success Story ~ Strathclyde Students’ Union and the University of Strathclyde The Summer Team Enterprise Programme (STEP) ~ University of St Andrews, University of St Andrews Students’ Association, and the Playfair Consultancy student society . -

Islands Strategy 2020 Preface

Islands Strategy 2020 Preface This is an exciting and energising time for Scotland’s islands given the Islands (Scotland) Act 2018, the National Islands T Plan and the developing Islands Deal. But there are significant challenges too, such as the impact of COVID-19 on the economies of the islands, the impact of climate change and the potential impact of projected population decline, especially in the Western Isles. The shape of education and research in the islands must be informed by both these challenges and these opportunities. As the only university with a physical base and delivering a tertiary educational offering within each of Scotland’s main island groupings, the University of the Highlands and Islands is inspired to deepen its engagement in the islands in order to make an incisive contribution to the sustainable and inclusive development of the islands in new and innovative ways. By utilising its strengths in further education, higher education, research and knowledge exchange, both within and outwith the islands, the university will work with stakeholders, taking a place- based, challenge-led and research-driven approach to key issues such as repopulation, workforce development in key sectors, the impact of climate change and talent attraction. This is an outward-facing strategy, one that builds on the unique strengths and profiles of the islands and draws on the university’s international connectivity with other island groupings around the world, and one which affirms, too, the growing importance of the islands cultural and historical connections with Nordic, Arctic and near Arctic neighbours. It is also one that will facilitate stronger cohesion of university activities across the islands and will provide new opportunities for the island-based academic activity to be at the centre for initiatives for the whole university and beyond.