Indigenous Perspectives on Cyclone Vulnerability Awareness and Mitigation Strategies for Remote Communities in the Gulf of Carpentaria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Quinkins, Percy J. Trezise, Dick Roughsey, Harpercollins Publishers Limited, 1978

The Quinkins, Percy J. Trezise, Dick Roughsey, HarperCollins Publishers Limited, 1978, 0001843702, 9780001843707, . A story about two groups of "Quinkins," the spirit people of the country of Cape York--the one group consisting of small, fat-bellied, bad fellows who steal children, and the other comprised of humorous, whimsical spirits.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/17kMNDu The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane , Kate DiCamillo, May 27, 2009, Juvenile Fiction, 210 pages. Edward Tulane, a cold-hearted and proud toy rabbit, loves only himself until he is separated from the little girl who adores him and travels across the country, acquiring new .... The Robe of Skulls , Vivian French, 2008, Juvenile Fiction, 200 pages. The sorceress Lady Lamorna has her heart set on a very expensive new robe, and she will stop at nothing--including kidnapping and black magic--to get the money to pay for it.. Coyote Columbus Story , Thomas King, William Kent Monkman, 1992, , 32 pages. Reinterprets the Christopher Columbus conquest story as a trickster tale, where Coyote the trickster is challenged by a funny looking red-haired man who has no interest in the .... Gb Horrorland: The Streets Of Panic Park , R. L. Stine, Jul 1, 2009, , 136 pages. Luke, Lizzy, and the other children have escaped HorrorLand, but to get out of Panic Park, where they are now trapped, they must join forces with an old enemy to defeat a .... Swamp Angel , Anne Isaacs, Jan 1, 2000, History, 40 pages. Along with other amazing feats, Angelica Longrider, also known as Swamp Angel, wrestles a huge bear, known as Thundering Tarnation, to save the winter supplies of the settlers ... -

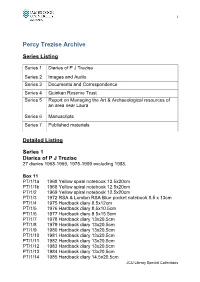

Percy Trezise Archive

1 Percy Trezise Archive Series Listing Series 1 Diaries of P J Trezise Series 2 Images and Audio Series 3 Documents and Correspondence Series 4 Quinkan Reserve Trust Series 5 Report on Managing the Art & Archaeological resources of an area near Laura Series 6 Manuscripts Series 7 Published materials Detailed Listing Series 1 Diaries of P J Trezise 27 diaries 1968-1969, 1975-1999 excluding 1988. Box 11 PT/1/1a 1968 Yellow spiral notebook 12.5x20cm PT/1/1b 1968 Yellow spiral notebook 12.5x20cm PT/1/2 1969 Yellow spiral notebook 12.5x20cm PT/1/3 1972 RSA & London RSA Blue pocket notebook 8.5 x 13cm PT/1/4 1975 Hardback diary 8.5x12cm PT/1/5 1976 Hardback diary 8.5x10.5cm PT/1/6 1977 Hardback diary 9.5x15.5cm PT/1/7 1978 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/8 1979 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/9 1980 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/10 1981 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/11 1982 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/12 1983 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/13 1984 Hardback diary 13x20.5cm PT/1/14 1985 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm JCU Library Special Collections 2 PT/1/15 1985 Hardback notebook 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/16 1986 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/17 1987 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/18 1989 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/19 1990 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/20 1991 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/21 1992 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/22 1993 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/23 1994 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/24 1995 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/25 1996 Hardback diary 14.5x20.5cm PT/1/26 1997 Soft cover diary 14.5x21.5cm PT/1/27 1999 Soft cover diary 14.5x21.5cm Series 2 Images & Audio containing slides, film strips, B&W Photos, VHS and audio tapes. -

Shannon Brett

Teacher Resource WELCOME TO THE 2O11 CIAF TEACHER RESOURCE WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM CONTEMPORARY ART? The integration of contemporary art into school and community learning enables educators to actively with engage with This resource has been developed by REACH (Regional Excellence in Arts and Culture Hubs) and CIAF (Cairns issues that affect our lives, provoking curiosity, encouraging dialogue, and igniting debate about the world around us. Indigenous Art Fair) to assist teachers and other educators support learning in the visual arts with an emphasis on contemporary Indigenous artist and their work. Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander artists address both current historical events and policies. These references help educators and students make connections across the curriculum and support interdisciplinary thinking. How to use this resource As artists continue to explore new technologies and media, the work they create encourages critical thinking and visual literacy in our increasingly media-saturated society. The CIAF 2O11 Teacher Resource defines three key phases for teachers - EARLY (P - 5), MIDDLE (6 - 9) and SENIOR (1O - 12). Each section is informed by and refers to Embedding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Perspectives in We want students to understand that contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art is part of a cultural dialogue Schools (EATSIPS). The DISCUSSION, LOOKING and ACTIVITY are to be seen as starting points and are not exclusive that concerns larger contextual frameworks, such as personal and cultural identity, family, community, and nationality. or finite. Please adopt, adapt, share and extend these ideas with your students and your peers. Curiosity, openness, and dialogue are important tools for engaging audiences in contemporary art. -

Differing Relations to Tradition Among Australian Indigenous Homeless

TDSR VOLUME XXVI NUMBER II 2015 59 D iffering Relations to Tradition amongst Australian Indigenous Homeless People PAUL MEMMOTT This essay explores a growing, visible form of Indigenous homelessness in contempo- rary Australia that can be termed “spiritual homelessness,” but which has not been ad- equately defined or understood using empirical evidence. Selected case studies provide a means of understanding the distinction between two categories of public-place-dwell- ing Aboriginal people: those who are reproducing their traditions in foreign places in a way that corresponds with the 2014 iaste conference theme “Mobility and the Reimagi- nation of Traditions”; and those who are unable to reconnect with their traditions and are spiritually bereft, corresponding with those who have no effective “Anchor to Their Tradi- tions in Place,” another conference theme. It concludes by offering suggestions for fur- ther research and project implementation in the area of Indigenous behavior settings. A growing, visible form of Indigenous homelessness in contemporary Australia is be- ing termed “spiritual homelessness,” but is currently without adequate definition or understanding based on empirical evidence. In this article I argue that this concept divides mobile Aboriginal public-place dwellers who are absent from their homeland and living itinerant lifestyles in towns and cities into two categories: those who have lost their traditions (spiritually homeless) and are chronically homeless, and those who are maintaining their traditions in a new itinerant lifestyle through the re-creation of tradi- tional place properties wherever they camp or reside. Paul Memmott is a Professor in the School The above analysis sets up a potential hypothesis about spiritual homelessness of Architecture and Institute for Social being a disconnect with homeland places and extended kin. -

MS 4706 Douglas and Doreen Belcher Papers 1954-1999

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Manuscript Finding Aid Index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library MS 4706 Douglas and Doreen Belcher Papers 1954-1999 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY……………………………………......page 2 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT…………………….....page 2 ACCESS TO COLLECTION………………………………………page 3 COLLECTION OVERVIEW…………………………………….....page 3 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE……………………………………………page 5 SERIES DESCRIPTION…………………………………………...page 6 Series 1: Diaries 1954-62, 1965-1972……………………..p.6 Series 2: Douglas Belcher 1999 ……………………………p.6 Series 3: ‘Windward, Leeward’ 2001……………………….p.7 Series 4: Research material for ‘Windward, Leeward’……p.7 Series 5: Photographs……………………………………….p.17 BOX LIST……………………………………………………………page 17 MS 4706 Douglas and Doreen Belcher papers COLLECTION SUMMARY Creator: Belcher, Douglas L. Title: Douglas and Doreen Belcher papers Collection no: MS 4706 Date Range: 1954-1999 (1914-2000) Extent: 1.06m; 8 boxes + 1 oversize box + 2 folders in Plan Cabinet PC7 Repository: Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Back to top CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT It is a condition of use of this finding aid, and of the collection described in it, that users ensure that any use of the information contained in it is sympathetic to the views and sensitivities of relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This includes: Language Users are warned that this finding Aid may contain words and descriptions which may be culturally sensitive and which might not normally be used in certain public or community contexts. Terms and descriptions which reflect the author’s attitude, or that of the period in which the manuscript was written, and which may be considered inappropriate today in some circumstances, may also be used. -

Aboriginal Elders Talk About Community- School Relationships on Mornington Island

‘We're the mob you should be listening to’: Aboriginal Elders talk about community- school relationships on Mornington Island Thesis submitted by Hilary BOND, BA, GradDipTeach, PostGradDipArts, MEd in March 2004 for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education, James Cook University Declaration on Sources I declare that this is my own work and has not been submitted in any form for another degree or diploma at any university or other institution of tertiary education. Information derived from the published or unpublished work of others has been acknowledged in the text and a list of references is given. Hilary Bond Date ii Statement of Access to Thesis I, the undersigned, author of this work, understand that James Cook University will make this thesis available for use within the University Library and, via the Australian Digital Theses network, for use elsewhere. I understand that, as an unpublished work, a thesis has significant protection under the Copyright Act. I do not wish to place any further restriction on access to this work. Hilary Bond Date iii Electronic Copy I, the undersigned, the author of this work, declare that the electronic copy of this thesis provided to the James Cook University Library is an accurate copy of the print thesis submitted, within the limits of the technology available. Hilary Bond Date iv Declaration on Ethics The research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted within the guidelines for research ethics outlined in the National Statement on Ethics Conduct in Research Involving Human (1999), the Joint NHMRC/AVCC Statement and Guidelines on Research Practice (1997), the James Cook University Policy on Experimentation Ethics. -

Southern Gulf of Carpentaria Sea Country Management, Needs and Issues

Living on Consultation Saltwater Country: Report Southern Gulf of Carpentaria Sea Country Management, Needs and Issues Healthy oceans: cared for, understood and used wisely for the benefit of all, now and in the future. Healthy oceans: cared for, understood and used wisely for the Prepared by Paul Memmott & Graeme Channells of Paul Memmott & Associates in association with Aboriginal Environments Research Centre University of Queensland on behalf of Carpentaria Land Council Aboriginal Corporation Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be warned that this document may contain images of and quotes from deceased persons. TITLE: SOUTHERN GULF OF CARPENTARIA SEA COUNTRY NEEDS AND ISSUES RESEARCH COPYRIGHT © National Oceans Office, 2004 DISCLAIMER This paper is not intended to be used or relied upon for any purpose other than to inform the management of marine resources. The Traditional Owners and native title holders of the regions discussed in this report have not had the opportunity for comment on this document and it is not intended to have any bearing on their individual or group rights, but rather to provide an overview of the use and management of marine resources in the Northern Planning Area for the Northern regional marine planning process. The views expressed in this report are not necessarily those of the Australian Government. The Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the contents of this report. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers should be warned that this document may contain images of and quotes from deceased persons. SOURCING Copies of this report are available from: The National Oceans Office Level 1, 80 Elizabeth St, Hobart GPO Box 2139 Hobart TAS 7001 Tel: +61 3 6221 5000 Fax: +61 3 6221 5050 www.oceans.gov.au REPRODUCTION: Information in this report may be reproduced in whole or in part for study or training purposes, subject to the inclusion of acknowledgement of the source and provided no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. -

WOOMERA 01 Sound Recordings Collected by the Woomera

Finding aid WOOMERA_01 Sound recordings collected by the Woomera Aboriginal Corporation, 1985, 1997-1999 Prepared April, 2016 by TQ Last updated 20 December 2016 Page 1 of 16 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening however please note that children are restricted from listening to Field Tape W98/4, Archive Item Number 026359. Restrictions on use This collection is restricted and may only be copied by clients who have obtained permission from the Woomera Aboriginal Corporation. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Permission must be sought from the Woomera Aboriginal Corporation as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1985, 1997-1999 Extent: 13 audiocassettes Production history These recordings were collected in July 1985 as well as from May 1997 through to 18 July 1999 at various locations on Mornington Island, Queensland. The recordings were created for the Lardil Songs Register project as part of AIATSIS research Grant number G98/6144. The purpose of the grant was to document the music from the Lardil language group as well as providing information on Lardil culture and heritage. RELATED MATERIAL Important: before you click on any links in this section, please read our sensitivity message. -

Introduction: a Return

`Introduction A RETURN In Australia’s far north, heat greets a visitor like a warm hug, envelop- ing the body as it exits an air-conditioned aeroplane. It’s still some time from what is known as the ‘Wet’, and residents here will have months of the ‘build up’ left to contend with before the clouds open and mon- soon storms bring sweet relief. For now, I’m covered in sweat, beads springing forth across the bridge of my nose and rivulets forming, running between my shoulder blades, and down the backs of my legs. Waves of heat rise from the tarmac where a small aeroplane waits, bak- ing in the midday sun, and blow towards the small building where a small number of passengers sit on rows of plastic chairs. I’m returning to the small Aboriginal community of Mornington Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia, a very remote island that I have been visiting since 2006 (see fi rst map in the frontmatter). The small commercial plane in which I’m travelling departed from the Australian east-coast city of Cairns, and is now making a brief stop in the small town of Normanton before fl ying on to the island community. My fel- low passengers are the usual mix of Aboriginal people and government workers from the range of service delivery agencies across the region. The fl ight attendant calls ‘all aboard’ and those making the onwards journey from Normanton to Mornington Island trudge across the tar- mac and resume their seats for take-off. -

15. Dugong Hunting As Changing Practice: Economic Engagement and an Aboriginal Ranger Program on Mornington Island, Southern Gulf of Carpentaria

15. Dugong Hunting as Changing Practice: Economic engagement and an Aboriginal ranger program on Mornington Island, southern Gulf of Carpentaria Cameo Dalley Introduction Chapters in this volume and papers in a special edition of The Australian Journal of Anthropology in 2009 address the intersection of anthropology with economics. A particular focus has been the ways in which Indigenous cultures might relate to conceivably more foreign notions of market economies. One prominent example, which conceptualised Aboriginal engagements in economic enterprise, was the ‘hybrid economy’ model offered by Altman (2001). The model featured three intersecting realms: the ‘market’, the ‘state’ and the (Aboriginal) ‘customary economy’. Important components of hybridity were the ‘linkages’, ‘dependencies’ and ‘cleavages’ between the various realms, which created particular opportunities, Altman (2001:5) argued, for economic development. Others, however, such as Martin (2003:3) and Merlan (2009:276), questioned the capacity of such sectors to exist in any way autonomously, instead pointing to their ‘recursive’ and ‘interrelated’ natures. These themes were similarly evident in the ethnographically rich analyses of local forms of economic relations by Austin-Broos (2003) and Smith (2003). These explorations in economic anthropology draw heavily on broader discourses about the degree to which Aboriginal culture could be considered to exist autonomously from the culture of broader Australia. These discussions were particularly advanced by the contributions of Merlan (1998, 2005, 2006). Merlan’s ethnography of the Aboriginal people of Katherine in the Northern Territory led her to propose a model of Aboriginal culture as having been transformed through interaction with others and, thus, having become thoroughly ‘intercultural’. -

Volume 9, Issue 2 August 2020 Read

NEWS Volume 9 Issue 2, August, 2020 About IACA A word from the IACA President IACA, the Indigenous Art Centre Alliance, is the peak body that supports and advocates for the community-based Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander art and cultural centres of Far North Queensland. Contents IACA works under the guidance and direction of a majority Volume 9 Issue 2, August, 2020 Indigenous Management Committee and is a not-for-profit organisation. There are currently 13 member art centres spread across the islands of the Torres Strait, the Gulf of Carpentaria, IACA Contacts Cape York and the tropical rainforest and coastal regions of Far 4 - 5 Elliot Koonutta: Email: [email protected] North Queensland. Pormpuraaw Art Centre Phone: +61 (0)7 4031 2745 6 - 7 Meredith Arkwookerum: Office Pormpuraaw Art Centre 16 Scott St Indigenous Art Centre Alliance members: Parramatta Park IACA Chair Phillip Rist. Image: IACA 8 - 9 Michael Norman: Queensland 4870 Badu Art Centre / Badhulgaw Kuthinaw Mudh - Badu Island Pormpuraaw Art Centre Australia An interview with the IACA Your thoughts on IACA’s response Bana Yirriji Art Centre - Wujal Wujal to COVID Travel restrictions and President Phillip Rist Lila Creek: Postal Erub Arts - Darnley Island cancellation of members conference 10 Bana Yirriji Art Centre P O Box 6587 and move to online training? Girringun Aboriginal Art Centre - Cardwell Has the lockdown affected you Cairns IACA has taken a very practical Gab Titui Cultural Centre personally? Queensland 4870 approach and provided online training 11 Sonya Creek: HopeVale Arts and Culture Centre It has been a blessing in disguise to Australia to its members which has worked well Bana Yirriji Art Centre be able to spend time with family.