An Archaeological Survey of Barbados Battery: the Good Shepherd Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial

Navigating the Atlantic World: Piracy, Illicit Trade, and the Construction of Commercial Networks, 1650-1791 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University by Jamie LeAnne Goodall, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Margaret Newell, Advisor John Brooke David Staley Copyright by Jamie LeAnne Goodall 2016 Abstract This dissertation seeks to move pirates and their economic relationships from the social and legal margins of the Atlantic world to the center of it and integrate them into the broader history of early modern colonization and commerce. In doing so, I examine piracy and illicit activities such as smuggling and shipwrecking through a new lens. They act as a form of economic engagement that could not only be used by empires and colonies as tools of competitive international trade, but also as activities that served to fuel the developing Caribbean-Atlantic economy, in many ways allowing the plantation economy of several Caribbean-Atlantic islands to flourish. Ultimately, in places like Jamaica and Barbados, the success of the plantation economy would eventually displace the opportunistic market of piracy and related activities. Plantations rarely eradicated these economies of opportunity, though, as these islands still served as important commercial hubs: ports loaded, unloaded, and repaired ships, taverns attracted a variety of visitors, and shipwrecking became a regulated form of employment. In places like Tortuga and the Bahamas where agricultural production was not as successful, illicit activities managed to maintain a foothold much longer. -

A Study of Chlamydia Trachomatis: Sexual Risk Behaviour, Infection and Prevention in the Australian Defence Force

A study of Chlamydia trachomatis: sexual risk behaviour, infection and prevention in the Australian Defence Force Stephen Mark Lambert Diploma of Teaching; Bachelor of Education; Masters in Public Health A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of Medicine I Abstract There is limited research in Australia focusing on C. trachomatis infection at a population level utilising systematic non-random recruitment methodologies. In addition, little is known in the Australian Defence Force (ADF) about the prevalence of C. trachomatis and of risk behaviours that may impact on sexual health. This study utilised an existing process in the ADF, the Annual Health Assessment, to source new information about C. trachomatis infection and about sexual risk and behaviour. The outcomes of this research may assist the ADF to maintain the health of personnel and consequently a high degree of operational preparedness, and may contribute to the understanding of C. trachomatis prevalence in Australia and across the world. The aims of this study were to determine the prevalence of C. trachomatis infection and to identify potential high risk populations in the ADF with a view to discussing secondary prevention interventions for the control of C. trachomatis infection within the ADF. Seven hundred and thirty-three ADF personnel were recruited into the study over a 24 month period. Participants were asked to complete an 8 page comprehensive survey about sexual behaviour and to provide a urine sample to be tested for C. trachomatis. Ethics approval was received from both the Australian Defence Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of Queensland Medical Research Ethics Committee. -

The West India Regiments

The West India Regiments By the mid-1790s, the wars with the French in the Caribbean were not going well for Britain and new sources of men were required to help defend the colonies. Issues with recruiting European troops and the high mortality rate amongst them meant that military minds had to consider new options with which to garrison and defend the West Indies. The local white population was not large enough to provide the number of men required, so attention turned to the large black population, mainly comprising slaves. Thus, Lieutenant General Sir John Vaughan proposed that a regiment should be raised composed of black soldiers. Unlike previous black regiments raised in the region, this was not to be a temporary measure but a new, permanent, regular infantry regiment of the British Army. The idea of a permanent corps of black soldiers outside their control horrified the leading figures of the Plantocracy, and their representative body in London, The West India Committee, attempted to use its influence in Government to prevent their formation. However, slave rebellions in both 1794 and 1795, as well as the conflict with the Maroons of Jamaica, coupled with the advice Ranger Regiments of senior officers who had been stationed The previous slave regiments were known as Ranger in the Caribbean and knew the difficulties Regiments, who were raised in times of desperation and of serving there, led Sir Henry Dundas, usually commanded by local officers. Ranger Regiments Secretary of State for War, to approve the tended only to serve on the island where they were created formation of two new regiments composed and slave-owners were paid for the services of their slaves, of black soldiers. -

Questioning Whiteness: “Who Is White?”

人間生活文化研究 Int J Hum Cult Stud. No. 29 2019 Questioning Whiteness: “Who is white?” ―A case study of Barbados and Trinidad― Michiru Ito1 1International Center, Otsuma Women’s University 12 Sanban-cho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan 102-8357 Key words:Whiteness, Caribbean, Barbados, Trinidad, Oral history Abstract This paper seeks to produce knowledge of identity as European-descended white in the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Trinidad, where the white populations account for 2.7% and 0.7% respectively, of the total population. Face-to-face individual interviews were conducted with 29 participants who are subjectively and objectively white, in August 2016 and February 2017 in order to obtain primary data, as a means of creating oral history. Many of the whites in Barbados recognise their interracial family background, and possess no reluctance for having interracial marriage and interracial children. They have very weak attachment to white hegemony. On contrary, white Trinidadians insist on their racial purity as white and show their disagreement towards interracial marriage and interracial children. The younger generations in both islands say white supremacy does not work anymore, yet admit they take advantage of whiteness in everyday life. The elder generation in Barbados say being white is somewhat disadvantageous, but their Trinidadian counterparts are very proud of being white which is superior form of racial identity. The paper revealed the sense of colonial superiority is rooted in the minds of whites in Barbados and Trinidad, yet the younger generations in both islands tend to deny the existence of white privilege and racism in order to assimilate into the majority of the society, which is non-white. -

Redescription of Hypoatherina Valenciennei and Its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans

Japanese Journal of Ichthyology 魚 類 学 雑 誌 Vol. 35, No. 2 1988 35 巻 2 号 1988年 Redescription of Hypoatherina valenciennei and its Relationships to Other Species of Atherinidae in the Pacific and Indian Oceans Walter Ivantsoff and Maurice Kottelat (Received December 23, 1986) Abstract A review of Tirant's collections and examination of types has resulted in the reidentifica- tion of Haplocheilus argyrotaenia Tirant as Hypoatherina valenciennei (Bleeker) which is found throughout the southwestern Pacific and as far north as Japan. The taxonomic status of H. valenciennei is clarified and Bleeker's emendation of the original specific epithet valenciennei to valenciennesi is rejected. The systematic position of this species is difficult to determine since H. valenciennei shows affinities with both Hypoatherina and Atherinomorus. In the light of the present knowledge, Bleeker's species appears to have greater affinities with Hypoatherina and is therefore placed in this genus. Recent reexamination of the types of Haplo- 1983). The genus Hypoatherina as defined by cheilus argyrotaenia Tirant, 1883, (unaccepted and Ivantsoff (1978) includes all those species with misspelt emendation of Haplochilus Agassiz, 1846, moderately long dorsal process of premaxilla but for Aplocheilus McClelland, 1839) has prompted not longer than eye diameter, lateral process of us to review the status of Hypoatherina valenciennei premaxilla short and broad, lower jaw coronoid (Bleeker, 1853a) which is considered to be the process highly elevated, distinct notch (sensory senior synonym of Tirant's species (thought by canal opening) in posterior margin of anterior him to be an aplocheilid). Although the systema- bony edge of preopercle near its lower corner, tic position of the Pacific atherinids is yet to be body slender and subcylindrical, midlateral band resolved, work to that end has already begun. -

British Commemorative Medals

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ BRITISH COMMEMORATIVE MEDALS Gold Medals 2074 Victoria, Golden Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by L C Wyon, after Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm and (reverse), Sir Frederick Leighton, crowned and veiled bust left, rev the Queen enthroned with figures of the arts and industry around her, 58mm, 89.86g, in red leather case of issue (BHM 3219). Extremely fine, damage to clasp of case. £900-1100 944 specimens struck, selling at 13 Guineas each 2075 Victoria, Diamond Jubilee 1887, Official Gold Medal, by G W -

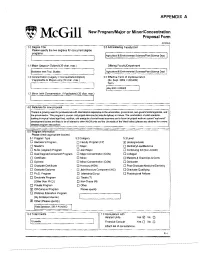

D08-38 Appendices a to E

APPENDIX A NewProgram/Major or Minor/Concentration , McGill Proposal Form (0712004) 1,0 DegreeTitle 2,0 Administering Faculty/Unit Please specifythe two degrees for concurrentdegree programs Agricultural &Environmental SdencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.1 Major (Legacy:: Subject)(30-char. max.) . Offering Faculty/Department IBarbadOS Inter.Trop. Studies Aglicultural & Environmental SciencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.2 Concentration(Legacy =ConcentrationJOption) 30 EffectiveTerm of Implementation If applicableto Majors only (30 char, max) (Ex. Sept 2004 == 200409) Term IMay 2009 1200905 1,3 Minor (withConcentration, if Applicable)(30 char. max.) I ~ I 4.0 Rationalefor new proposal I There tsa growing need forprofessionals with international experience intheunlversilles, government, non-govemmental agencies. and theprivate sector. This program is course- and project-intensive butinterdisciplinary in nature. Thecombination ofsolk! academic training intropical Island a91i-fooo. nutrition, and energy Ina tourist-based economy anda focus onproject work oncurrent 'realwortd' development issues arelikely tobe ofinterest toother McGill units and the University of thewest Indies (please see attached fora more detailed program description). - 5.0 ProgramInformation Please check appropriate boxtes) 5.1 Program Type 5.2 Category 5.3 Level o Bachelor'sProgram o FacultyProgram(FP) . ~ Undergraduate o Master's o Major o DentistryfLawlMedicine o M.Sc. (Applied) Program o Joint Major o Continuing Ed (Non-Credit) o Dual Degree/ConcurrentProgram o MajorConcentration -

White Racial Identity Development Model for Adult Educators

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press Adult Education Research Conference 2009 Conference Proceedings (Chicago, IL) White Racial Identity Development Model for Adult Educators Carole L. Lund Alaska Pacific University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/aerc Part of the Adult and Continuing Education Administration Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Lund, Carole L. (2009). "White Racial Identity Development Model for Adult Educators," Adult Education Research Conference. https://newprairiepress.org/aerc/2009/papers/38 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Adult Education Research Conference by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. White Racial Identity Development Model for Adult Educators Carole L. Lund, Ed.D. Alaska Pacific University, USA Abstract: The white racial identity development model has implications for educators wishing to address racism. There are six pathways an adult educator might explore to understand where they are in the white racial identity development process—status quo to ally. Inadequacy in addressing racism paralyzes many from taking any action. The white racial identity development process leads one to progress from the status quo to become an advocate or ally. Frow and Morris (2000) addressed the identity of scholars: “Questions of identity and community are framed not only by issues of race, class, and gender but by a deeply political concern with place, cultural memory, and the variable terms of these scholars’ access to an ‘international’ space of debate” (p. -

Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong By

Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong by Cecilia Louise Chu A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair Professor C. Greig Crysler Professor Eugene F. Irschick Spring 2012 Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Copyright 2012 by Cecilia Louise Chu 1 Abstract Speculative Modern: Urban Forms and the Politics of Property in Colonial Hong Kong Cecilia Louise Chu Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture University of California, Berkeley Professor Nezar AlSayyad, Chair This dissertation traces the genealogy of property development and emergence of an urban milieu in Hong Kong between the 1870s and mid 1930s. This is a period that saw the transition of colonial rule from one that relied heavily on coercion to one that was increasingly “civil,” in the sense that a growing number of native Chinese came to willingly abide by, if not whole-heartedly accept, the rules and regulations of the colonial state whilst becoming more assertive in exercising their rights under the rule of law. Long hailed for its laissez-faire credentials and market freedom, Hong Kong offers a unique context to study what I call “speculative urbanism,” wherein the colonial government’s heavy reliance on generating revenue from private property supported a lucrative housing market that enriched a large number of native property owners. Although resenting the discrimination they encountered in the colonial territory, they were able to accumulate economic and social capital by working within and around the colonial regulatory system. -

Kirk King Appointed New GM of Berger Paints

Established October 1895 See inside Monday February 17, 2020 $1 VAT Inclusive High cost concern MINISTER of Maritime Affairs and the Blue Economy,Kirk Humphrey says he is concerned about the high cost of some of the eco-friendly food-grade products available on the local market. He made the comments after touring COT Holdings at Newton Industrial Estate, Christ Church, stating that it is imperative that a way is found to reduce the cost of the inputs so that the products can be sold more competitively. “Some of the costs that you see on some of these items are not in sync with what they have had to pay, so that what you see reflected as the final price has no bearing to the ban that we have put on single use plastics. I have said before and I am saying it now, we have persons in Barbados, the corporate companies [who] have a responsibility to engage in practices that are in sync with Barbadian values,” he said. He continued, “There is an ethical kind of behaviour that should bind all of us.” Haynesville Youth Group Dancers and Dancin’ Africa performing at the Holetown Monument. Minister Humphrey said in the process of some of his ministry’s investigations, when the cost of the containers and the selling price were compared,“it was insane”, hinting that the latter was extremely high. With that in mind, he said they have BIGGER, BETTER also heard that there are some persons who are Holetown Festival attempting to sell the banned single use plastics quietly, despite the fact off to grand start that it is illegal to do so.