The Analysis of Ceramic Symbolism from the First Street Site in Barbados

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

D08-38 Appendices a to E

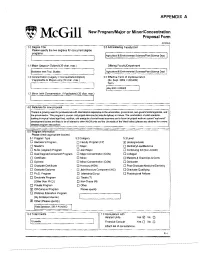

APPENDIX A NewProgram/Major or Minor/Concentration , McGill Proposal Form (0712004) 1,0 DegreeTitle 2,0 Administering Faculty/Unit Please specifythe two degrees for concurrentdegree programs Agricultural &Environmental SdencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.1 Major (Legacy:: Subject)(30-char. max.) . Offering Faculty/Department IBarbadOS Inter.Trop. Studies Aglicultural & Environmental SciencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.2 Concentration(Legacy =ConcentrationJOption) 30 EffectiveTerm of Implementation If applicableto Majors only (30 char, max) (Ex. Sept 2004 == 200409) Term IMay 2009 1200905 1,3 Minor (withConcentration, if Applicable)(30 char. max.) I ~ I 4.0 Rationalefor new proposal I There tsa growing need forprofessionals with international experience intheunlversilles, government, non-govemmental agencies. and theprivate sector. This program is course- and project-intensive butinterdisciplinary in nature. Thecombination ofsolk! academic training intropical Island a91i-fooo. nutrition, and energy Ina tourist-based economy anda focus onproject work oncurrent 'realwortd' development issues arelikely tobe ofinterest toother McGill units and the University of thewest Indies (please see attached fora more detailed program description). - 5.0 ProgramInformation Please check appropriate boxtes) 5.1 Program Type 5.2 Category 5.3 Level o Bachelor'sProgram o FacultyProgram(FP) . ~ Undergraduate o Master's o Major o DentistryfLawlMedicine o M.Sc. (Applied) Program o Joint Major o Continuing Ed (Non-Credit) o Dual Degree/ConcurrentProgram o MajorConcentration -

Kirk King Appointed New GM of Berger Paints

Established October 1895 See inside Monday February 17, 2020 $1 VAT Inclusive High cost concern MINISTER of Maritime Affairs and the Blue Economy,Kirk Humphrey says he is concerned about the high cost of some of the eco-friendly food-grade products available on the local market. He made the comments after touring COT Holdings at Newton Industrial Estate, Christ Church, stating that it is imperative that a way is found to reduce the cost of the inputs so that the products can be sold more competitively. “Some of the costs that you see on some of these items are not in sync with what they have had to pay, so that what you see reflected as the final price has no bearing to the ban that we have put on single use plastics. I have said before and I am saying it now, we have persons in Barbados, the corporate companies [who] have a responsibility to engage in practices that are in sync with Barbadian values,” he said. He continued, “There is an ethical kind of behaviour that should bind all of us.” Haynesville Youth Group Dancers and Dancin’ Africa performing at the Holetown Monument. Minister Humphrey said in the process of some of his ministry’s investigations, when the cost of the containers and the selling price were compared,“it was insane”, hinting that the latter was extremely high. With that in mind, he said they have BIGGER, BETTER also heard that there are some persons who are Holetown Festival attempting to sell the banned single use plastics quietly, despite the fact off to grand start that it is illegal to do so. -

Climate Change and Coastal Human Settlements: Barbados and Guyana

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean LIMITED LC/CAR/L.326 22 October 2011 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH AN ASSESSMENT OF THE ECONOMIC IMPACT OF CLIMATE CHANGE ON THE COASTAL AND HUMAN SETTLEMENTS SECTOR IN BARBADOS __________ This document has been reproduced without formal editing. i Acknowledgement The Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) Subregional Headquarters for the Caribbean wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Maurice Mason, consultant, in the preparation of this report. ii Table of contents I. THE INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 A. OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................... 1 B. OBJECTIVE .......................................................................................................................... 1 C. GENERAL METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH ......................................................................... 2 II. MANIFESTATION OF CLIMATE CHANGE ......................................................................... 3 A. SEA LEVEL RISE ................................................................................................................. 3 B. CHANGE IN WEATHER CONDITION ..................................................................................... 5 1 .Projection for the Atlantic Storm ........................................................................... -

Popular Culture and the Remapping of Barbadian Identity

“In Plenty and In Time of Need”: Popular Culture and the Remapping of Barbadian Identity by Lia Tamar Bascomb A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies in the Graduate Division of University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Leigh Raiford, Chair Professor Brandi Catanese Professor Nadia Ellis Professor Laura Pérez Spring 2013 “In Plenty and In Time of Need”: Popular Culture and the Remapping of Barbadian Identity © 2013 by Lia Tamar Bascomb 1 Abstract “In Plenty and In Time of Need”: Popular Culture and the Remapping of Barbadian Identity by Lia Tamar Bascomb Doctor of Philosophy in African American Studies University of California at Berkeley Professor Leigh Raiford, Chair This dissertation is a cultural history of Barbados since its 1966 independence. As a pivotal point in the Transatlantic Slave Trade of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, one of Britain’s most prized colonies well into the mid twentieth century, and, since 1966, one of the most stable postcolonial nation-states in the Western hemisphere, Barbados offers an extremely important and, yet, understudied site of world history. Barbadian identity stands at a crossroads where ideals of British respectability, African cultural retentions, U.S. commodity markets, and global economic flows meet. Focusing on the rise of Barbadian popular music, performance, and visual culture this dissertation demonstrates how the unique history of Barbados has contributed to complex relations of national, gendered, and sexual identities, and how these identities are represented and interpreted on a global stage. This project examines the relation between the global pop culture market, the Barbadian artists within it, and the goals and desires of Barbadian people over the past fifty years, ultimately positing that the popular culture market is a site for postcolonial identity formation. -

JIB Group Holdings Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements 31

Company number: 02956529 JIB Group Holdings Limited Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 JIB Group Holdings Limited Company number: 02956529 Contents Company Information 1 Strategic Report 2 to 3 Directors' Report 4 to 5 Statement of Directors' Responsibilities 6 Independent Auditor’s Report 7 to 9 Profit and Loss Account 10 Statement of Comprehensive Income 11 Balance Sheet 12 Statement of Changes in Equity 13 Notes to the Financial Statements 14 to 41 JIB Group Holdings Limited Company number: 02956529 Company Information Directors J Flahive M D Jones Company secretary Marsh Secretarial Services Limited Registered office The St Botolph Building 138 Houndsditch London EC3A 7AW Page 1 JIB Group Holdings Limited Company number: 02956529 Strategic Report for the Year Ended 31 December 2019 The directors present their strategic report for JIB Group Holdings Limited ('the Company') for the year ended 31 December 2019. Principal activities Until 1 April 2019, the Company formed part of the Managed Services Division of Jardine Lloyd Thompson Group plc (‘the JLT Group’). On 1 April 2019 the JLT Group was acquired by Marsh & McLennan Companies, Inc (‘MMC’ or ‘the Group’). The Company acts as an intermediary holding company and expects to trade for the foreseeable future. Business review Profit before taxation amounts to £2,936,364,664 (2018: Loss of £(7,960,953)). During the year, and as part of a wider Group restructure to integrate the JLT Group companies with the MMC companies, the Company adopted new Articles of Association to facilitate the following: • On the 24 June 2019 the Company was transferred the entire legal and beneficial interest in a loan from JLT US. -

I'm Swimming in the Turquoise Waters of a Secluded Beach on the West Coast of Barbados

Photo by Susana Lay I'm swimming in the turquoise waters of a secluded beach on the west coast of Barbados. The sun is shimmering on the undulating water. I raise my eyes to see some boats drifting toward the horizon and wish I could pause this scene. From the shore, one of my friends waves me over as she makes a toast with a glass of wine. I submerge myself into the glassy waters and ask myself: If this is not paradise, then what is? Barbados has everything you need for an absolute disconnection: deep-rooted culture, fish fries and rum, and soca music, all against a backdrop best described as paradise. Where to Stay In Barbados you are never more than 12 miles from the sea. The best way to understand the island is to divide the map into five parts: the tranquil upper west coast, the tourist central south coast, the wild east coast bordering the Atlantic, the island's interior, and the capital of Bridgetown, or “Little England” as many call it. Depending on what you're looking for during your stay, you'll find Barbados has a lodging to fit every taste and budget. My friends and I decide to rent a three-bedroom house steps from the ocean, with a comfortable kitchen, a small plunge pool and a lovely deck overlooking the sea. There's no better way to mix with locals and have a real sense of place than by being part of a neighborhood, buying groceries like everyone else and waving hi to the waiters at the next-door restaurant (which, by the way, is called Fish Pot Restaurant and is a gourmet, upscale spot). -

Final-Admission-Document.Pdf

Proof 5: 29.5.14 THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt about the contents of this document or the action that you should take, you should consult a person authorised under FSMA who specialises in advising on the acquisition of shares and other securities. If you are not in the United Kingdom you should immediately consult another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. This document is an AIM admission document drawn up in accordance with the AIM Rules for the purpose of the application for admission to trading of the entire issued and to be issued share capital of the Company on AIM. This document does not constitute a prospectus for the purposes of the Prospectus Rules and it has not been, and will not be, approved by or filed with the FCA under the Prospectus Rules. This document contains no offer of transferable securities to the public within the meaning of section 102B of FSMA, the Companies Acts 1985 or 2006 of England and Wales or otherwise. AIM is a market designed primarily for emerging or smaller companies to which a higher investment risk tends to be attached than to larger or more established companies. AIM securities are not admitted to the Official List of the UK Listing Authority. The AIM Rules for Companies are less demanding than those of the Official List of the UK Listing Authority. A prospective investor should be aware of the risks of investing in such companies and should make the decision to invest only after careful consideration and, if appropriate, consultation with an independent financial adviser. -

RESOURCE BOOKLET 2008 CELEBRATING OUR RICH HERITAGE TREASURES of BARBADOS PEOPLE, PLACES, THINGS Page 4 Resource Booklet

CO-ORDINATOR : Mrs. Margaretta Sealy Media Resource Department PHOTOGRAPHER : Mr. Basil Bishop Media Resource Department Layout and Design : Miss. Amour Chandler Media Resource Department STAFF : Media Resource Department Designed & Printed by: The Media Resource Department Ministry of Education and Human Resource Development Elsie Payne Complex Constitution Road St. Michael Resource Booklet Page 3 RESOURCE BOOKLET 2008 CELEBRATING OUR RICH HERITAGE TREASURES OF BARBADOS PEOPLE, PLACES, THINGS Page 4 Resource Booklet MESSAGE FROM MR. LEMUEL JORDAN CHIEF MEDIA RESOURCE OFFICER Technology has certainly grown by leaps and bounds over the past ten years and the MRD is positioning itself to ensure that Barbados’ educational system remains on the cutting edge of Information and Communication Technologies. We are presently in the process of rebranding and gradually making our resources available online for easy access by educators. This booklet is available electronically on our Public Broadcast Service for Education (PBS-E) which was launched by the Hon. David Thompson, Prime Minister of Barbados on October 22, 2008. In addition to the website www.pbsebarbados.org there is an educational radio station which has already been tested and there are plans for Mr. Lemuel Jordan Educational Television in the New Year. In recognizing the treasures of the past we look to Celebrating Our Heritage While the future with confidence as we seek to engage Advancing with Technology young minds utilizing technologies with which they The history of our country reflects a nation with a are most comfortable. As educators we have to be rich heritage that needs to be celebrated. Our empowered to utilize all means of modern people have been an invaluable resource and technology to realize individual and curriculum upholding the motto of ‘Pride and Industry’ has goals. -

W&M's International Tennis Team

A PUBLICATION OF THE REVES CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES AT WILLIAM & MARY VOL. 7, NO. 2, SPRING 2015 W&M’s International Tennis Team ALSO: A Thousand Years of Environmental Change in Polynesia Senator Tim Kaine visits AidData A PUBLICATION OF THE REVES CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDIES AT WILLIAM & MARY VOL. 7, NO. 2, SPRING 2015 3 5 21 AROUND THE WORLD FEATURES NEWSMAKERS 2 Alumna Profile: Millen Zerabruk 8 Cross-cultural and Cross- 17 Distinguished Visitors and ’05 Generational Connections with Milestones Japan 3 Jennifer Kahn: A Thousand Years 18 New in Print; Excerpt from The of Environmental Change 10 Senator Kaine visits AidData Cosmopolitan First Amendment by Timothy Zick 5 Studying in Singapore: A Semester 11 Virtual Conversation Partner on the Other Side of the Planet Program 19 Ellen Hazelkorn on Higher Education 7 A Swede in Williamsburg: Jimmy 14 W&M’s International Tennis Team Eriksson 20 Reves 2015 Faculty Fellows 21 2014 Study Abroad Photo Contest Winners Editor: Kate Hoving, Public Relations Manager, Reves Center for International Studies Graphic Designer: Rachel Follis, Creative Services Contributors: Shelby Roller ’15; Akshay Deverakonda ’15; Frank Shatz; Christopher Katella, AidData; Tehmina Khwaja and Pamela Eddy, W&M School of Education On the cover: Olivia Thaler (left) and Jeltje Loomans celebrate a point won. Photo by Jim Agnew. WORLD MINDED FROM THE DIRECTOR he name of our biannual In this regard, it’s hard to think of a magazine about the Reves place with greater world-mindedness TCenter for International Studies than William & Mary. Founded over pays subtle homage to the deep and three centuries ago by visionary abiding tradition of global engagement Virginians with the support of at William & Mary. -

University of Warwick Institutional Repository: a Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Phd at The

University of Warwick institutional repository: http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick http://go.warwick.ac.uk/wrap/36383 This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. a_ HISTORY AND CULTURAL IDENTITY: BARBADIAN SPACE AND THE LEGACY OF EMPIRE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY Marcia P. A. Burrowes University of Warwick Centre for British and Comparative Cultural Studies February 2000 ii I dedicate this thesis to my Mother, Hazel Patricia Burrowes, and to the memory of Captain Faye Darlington (1961-1998) iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES Vi LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Vii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix DECLARATION Xi ABSTRACT Xii Introduction 1 Chapter One : History, Historicality and its Narratives I Introduction 13 II The Island 21 DI The Missing Early Inhabitants 27 IV Colonisation 38 a) The Controversial Names 39 b) The Landing Party and the Rest 46 c) 'a quintessential New World slave society' 51 V Emancipation and Independence 56 a) 'iron tooth'd ratchets' 56 b) Emancipation Day 1997 57 VI Summary 65 Chapter Two: Barbadian Cultural Identity and its Contradictions I Identity and Fluidity 68 a) Wrestling with the Statue of Nelson 68 b) 'Living in the shadow of Englishness' -

Handbook 2, Living in Barbados

WASHBURN UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW LEARN LAW IN THE WEST INDIES SUMMER LAW PROGRAM IN BARBADOS INFORMATION HANDBOOK PART TWO “LIVING IN BARBADOS” ****TAKE THIS HANDBOOK WITH YOU**** TABLE OF CONTENTS I. CUSTOMS CHECKLIST ............................................................................................................. 1 II. PACKING ....................................................................................................................................... 1 A. Packing Suggestions .......................................................................................................... 2 B. Weather .............................................................................................................................. 5 III. TRANSPORTATION FROM AIRPORT TO CAMPUS ........................................................... 5 A. General Transportation .................................................................................................... 5 B. Driving ................................................................................................................................ 6 IV. PRACTICAL INFORMATION.................................................................................................... 6 A. Barbados ............................................................................................................................ 6 B. The University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus ................................................... 7 C. Guests and Visitors ........................................................................................................... -

Accolades.Pdf

FALLFALL 20192019 FACULTY, STAFF, AND STUDENT ACHIEVEMENTS PUBLICATIONS Bahadir Akcam, associate professor of Robert Barron, assistant professor of industrial Jingru Benner, assistant professor of Jingzhou Zhao, assistant professor of business information systems engineering and engineering management mechanical engineering mechanical engineering Bahadir Akcam, associate professor of business information Robert Barron, assistant professor of industrial engineering systems, coauthored an article titled “Research Design and and engineering management, published, with M. Hill, “A Major Issues in Developing Dynamic Theories by Secondary Wedge or a Weight? Critically Examining Nuclear Power’s Analysis of Qualitative Data” for the Systems journal (2019: 7, Viability as A Low-carbon Energy Source from an Intergenera- 3: 40). tional Perspective,” in Energy Research and Social Science (2019: 50, pp. 7-17). David Baker, associate professor of pharmacy administration, published and presented, with Izabela Collier, clinical asso- Jingru Benner, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, ciate professor of ambulatory care, Courtney Doyle-Camp- published the following; bell, clinical associate professor of ambulatory care, Melissa With Mehdi Mortazavi, assistant professor of mechanical Mattison, clinical associate professor of community care, engineering, Anthony Santamaria, assistant professor of me- Katelyn Harrison, clinical associate professor of ambulato- chanical engineering, S. Su, and T. Nguyen, “A Novel Biomimet- ry care, Quan Wei, instructional