A Bioarchaeological Investigation of Two Unmarked Graveyards in Bridgetown, Barbados

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Studies on the Circulation of the Atmospheres of the Sun

166 MONTHLY WEATEER REVIEW. APRIL,1904 STUDIES ON THE CIRCULATION OF THE ATMOSPHERES strato-cumulus as belonging to the cumulus level, and have OF THE SUN AND OF THE EARTH. used the reduction factor 0.5 instead of 0.9 in drawing the By Prof. FRANKH. BIGELOW. charts. V.-RESULTS OF THE NEPHOSCOPE OBSERVATIONS IN THE At Bridgetown the vector systems of the alto-stratus and WEST INDIES DURING THE TEARS 1899-1903. t,he cirro-cumulus levels have apparently been interchanged. As they now stand at Bridgetown they are inconsistent with METEODS OF OBSERVATION AND REDUCTION. the flow of air as determined at Basseterre, Roseau, Port of The observers of the United States Weather Bureau OCCII- Spain, and Willemstad; but if they are transposed, then there pied eleven stations in the West Indies during the years 1899- is harmony. The observation sheets indicate that the ob- 1903, and the opportunity was utilized to make a survey of the servers hare an unusually large number of cirro-cumulus en- motions of the atmosphere in that region of the Tropics by tries and comparatively few alto-stratus, so that apparently means of nephoscopes. they were accustomed to name many alto-stratus clods as The instruments were of the Marvin pattern, and the metliocl cirro-cumulus clouds. It is not easy to secure identical esti- of observation, to obtain the aziniuth and velocity of motion, mates of cloud forms at so many independent stations as we was identical with that described in t8heReport of the Chief of have used, and these fern instances of apparent discrepancies the Weather Bureau, 1S9S-99, T’ol. -

Strengthening Strategic Trade Controls in the Caribbean

Provisional programme Strengthening strategic trade controls in the Caribbean: preventing WMD proliferation and safeguarding borders Tuesday 4 – Thursday 6 October 2016 | WP1505 To be held in Bridgetown, Barbados Since the CARICOM-UNSCR 1540 Programme convened the forum on Public-Private Partnerships to Implement UNSCR 1540 in October 2013, CARICOM Member States have consistently expressed their desire to receive technical assistance in order to develop the needed regulatory infrastructure and enforcement capacity to effectively control strategic trade. These requests were again tabled at the recent Commodity Identification Training workshop in Kingston, Jamaica in October where the CARICOM-UNSCR 1540 and the National Nuclear Security Administration held a follow-up initiative to acquaint primarily enforcement and customs officials, with methodologies to identify nuclear and radiological commodities, particularly within a port setting. This forum will address this need by: 1. Developing a Strategic Trade Licensing Framework (STLF) that CARICOM Member States can leverage to prevent the movement of strategic commodities across regional ports and borders; 2. Draw up a Control List Construct (CLC) to assist CARICOM Member States in meeting obligations under UNSCR 1540; 3. Propose training in effective risk analysis and in targeting strategies to prevent the export, re-export, import, transit or transhipment of strategic goods and training in the utilisation of trade information/intelligence to detect suspect transfers and to minimise impediments -

Memorial Day Sale Exclusive Rates· Book a Balcony Or Above and Receive up to $300 Onboard Credit ^ Plus 50% Reduced Deposit'

Memorial Day Sale Exclusive Rates· Book a Balcony or above and receive Up to $300 Onboard Credit ^ plus 50% Reduced Deposit' Voyage No. Sail Date Itinerary Voyage Description Nights Japan and Alaska Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Sakaiminato, Busan, Sasebo, Kagoshima, Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross Q216B 5/8/2022 International DateLine(Cruise-by), Anchorage(Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Japan and Alaska 38 Victoria, Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross International Date Line (Cruise-by), Anchorage (Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise- Q217B 5/17/2022 by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier Japan and Alaska 29 (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Tokyo (tours from Yokohama), Hakodate, Aomori, Otaru, Cross International Date Line (Cruise-by), Anchorage (Seward), Hubbard Glacier (Cruise- Q217N 5/17/2022 Japan and Alaska 19 by), Juneau, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Alaska Q218N 6/4/2022 Vancouver, Glacier Bay National Park (Cruise-by), Haines, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Juneau, Sitka, Ketchikan, Victoria, Vancouver Alaska 10 Q219 6/14/2022 Vancouver, Juneau, Hubbard Glacier (Cruise-by), Skagway, Glacier Bay National Park -

School Handbook

Bridgetown REGIONAL COMMUNITY SCHOOL School Handbook Principals’ Message Welcome to our learning community at Bridgetown Regional Community School! BRCS endeavors to provide students with an excellent education delivered by a dedicated and extremely knowledgeable staff. In today’s world, students must be provided with learning experiences that prepare them for the future by stressing such learnings as aesthetic expression, citizenship, communication, personal development, problem solving and technological competence. Our school will continue to focus on the three R’s – RIGHTS, RESPECT and RESPONSIBILITY, which will strongly support the development of a warm, caring and safe environment. Students – this school is here to help you grow and develop. The more you give to it, the more you will receive from it! Please feel free to call or email us at any time if you have any questions, suggestions or concerns. Darlene Thomas & Tammy Foster-Veinot BRCS Mission Statement Bridgetown Regional Community School is a community of staff and students that is committed to individual achievement and collaborative work in the implementation of a rich, dynamic, diversified and differentiated curriculum in a climate that is safe and welcoming for all. School Configuration BRCS consists of a Pre-primary program, an Elementary Section (P-5), a Middle Level (Grades 6-8) and a Senior High (grades 9-12). The school follows a fixed 8-day cycle. The School Calendar link on the BRCS webpage outlines the school year with days of the cycle identified. Daily Schedule -

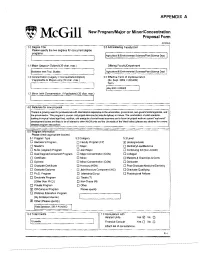

D08-38 Appendices a to E

APPENDIX A NewProgram/Major or Minor/Concentration , McGill Proposal Form (0712004) 1,0 DegreeTitle 2,0 Administering Faculty/Unit Please specifythe two degrees for concurrentdegree programs Agricultural &Environmental SdencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.1 Major (Legacy:: Subject)(30-char. max.) . Offering Faculty/Department IBarbadOS Inter.Trop. Studies Aglicultural & Environmental SciencesIPlant Science Dept. 1.2 Concentration(Legacy =ConcentrationJOption) 30 EffectiveTerm of Implementation If applicableto Majors only (30 char, max) (Ex. Sept 2004 == 200409) Term IMay 2009 1200905 1,3 Minor (withConcentration, if Applicable)(30 char. max.) I ~ I 4.0 Rationalefor new proposal I There tsa growing need forprofessionals with international experience intheunlversilles, government, non-govemmental agencies. and theprivate sector. This program is course- and project-intensive butinterdisciplinary in nature. Thecombination ofsolk! academic training intropical Island a91i-fooo. nutrition, and energy Ina tourist-based economy anda focus onproject work oncurrent 'realwortd' development issues arelikely tobe ofinterest toother McGill units and the University of thewest Indies (please see attached fora more detailed program description). - 5.0 ProgramInformation Please check appropriate boxtes) 5.1 Program Type 5.2 Category 5.3 Level o Bachelor'sProgram o FacultyProgram(FP) . ~ Undergraduate o Master's o Major o DentistryfLawlMedicine o M.Sc. (Applied) Program o Joint Major o Continuing Ed (Non-Credit) o Dual Degree/ConcurrentProgram o MajorConcentration -

Aguascalientes, Mexico Amman, Jordan Amsterdam, Nederlands St

Airport Code Location AGU Aguascalientes, Mexico AMM Amman, Jordan AMS Amsterdam, Nederlands ANU St. George, Antigua & Barbuda ARN Stockholm, Sweden ATH Athens, Greece AUA Oranjestad, Aruba AUH Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates BCN Barcelona, Spain BDA Hamilton, Bermuda BGI Bridgetown, Barbados BJX Silao, Mexico BNE Brisbane, Australia BOG Bogota, Colombia BON Kralendijk, Caribbean Netherlands BRU Brussels, Belgium BSB Brasilia, Brazil BZE Belize City, Belize CCS Caracas, Venezuela CDG Paris, France CPH Copenhagen, Denmark CUN Cancun, Mexico CUR Willemstad, Curacao CUU Chihuahua, Mexico CZM Cozumel, Mexico DEL New Delhi, India DOH Doha, Qatar DUB Dublin, Ireland DUS Dusseldorf, Germany DXB Dubai, United Arab Emirates EDI Edinburgh, United Kingdom EZE Buenos Aires, Argentina FCO Rome, Italy FPO Freeport, Bahamas FRA Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany GCM Georgetown, Cayman Islands GDL Guadalajara. Mexico GGT George Town, Bahamas GIG Rio de Janeiro, Brazil GLA Glasgow, United Kingdom GRU Sao Paulo, Brazil GUA Guatemala City, Guatemala HEL Helsinki, Finland HKG Hong Kong, Hong Kong ICN Seoul, South Korea IST Instanbul, Turkey JNB Johannesburg, South Africa KIN Kingston, Jamaica LHR London, United Kingdom LIM Lima, Peru LIR Liberia, Costa Rica LIS Lisbon, Portugal LOS Lagos, Nigeria MAD Madrid, Spain MAN Manchester, United Kingdom MBJ Montego Bay, Jamaica MEX Mexico City, Mexico MGA Managua, Nicaragua MLM Morelia, Mexico MTY Monterrey, Mexico MUC Munich, Germany MXP Milan, Italy MZT Mazatlan, Mexico NAS Nassau, Bahamas NRT Tokyo, Japan PAP Port-au-Prince, -

Kirk King Appointed New GM of Berger Paints

Established October 1895 See inside Monday February 17, 2020 $1 VAT Inclusive High cost concern MINISTER of Maritime Affairs and the Blue Economy,Kirk Humphrey says he is concerned about the high cost of some of the eco-friendly food-grade products available on the local market. He made the comments after touring COT Holdings at Newton Industrial Estate, Christ Church, stating that it is imperative that a way is found to reduce the cost of the inputs so that the products can be sold more competitively. “Some of the costs that you see on some of these items are not in sync with what they have had to pay, so that what you see reflected as the final price has no bearing to the ban that we have put on single use plastics. I have said before and I am saying it now, we have persons in Barbados, the corporate companies [who] have a responsibility to engage in practices that are in sync with Barbadian values,” he said. He continued, “There is an ethical kind of behaviour that should bind all of us.” Haynesville Youth Group Dancers and Dancin’ Africa performing at the Holetown Monument. Minister Humphrey said in the process of some of his ministry’s investigations, when the cost of the containers and the selling price were compared,“it was insane”, hinting that the latter was extremely high. With that in mind, he said they have BIGGER, BETTER also heard that there are some persons who are Holetown Festival attempting to sell the banned single use plastics quietly, despite the fact off to grand start that it is illegal to do so. -

The Analysis of Ceramic Symbolism from the First Street Site in Barbados

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-2006 The Analysis of Ceramic Symbolism from the First Street Site in Barbados Aya Hashimoto Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hashimoto, Aya, "The Analysis of Ceramic Symbolism from the First Street Site in Barbados" (2006). Master's Theses. 3863. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3863 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ANALYSIS OF CERAMIC SYMBOLISM FROM THE FIRST STREET SITE IN BARBADOS by Aya Hashimoto A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillmentof the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 2006 @2006 Aya Hashimoto ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Michael S. Nassaney for taking the time to discuss with me his perception of the topics contained herein. His guidance. and advice on organizing my thoughts were invaluable and necessary to complete this work. I also thank the members of my graduate committee, Dr. Laura Spielvogel and Dr. Frederick H. Smith for taking the time to review my work, and lending important advice. In addition, I would also like to thank my friends Adriana, Cleothia, and Maxwell who supported me in finishing my work. -

BRIDGETOWN, BARBADOS Disembark: 0800 Saturday, November 22 Onboard: 1800 Monday, November 24

BRIDGETOWN, BARBADOS Disembark: 0800 Saturday, November 22 Onboard: 1800 Monday, November 24 Brief Overview: This historic Caribbean town has no shortage of things to do and sites to see. Bridgetown has been known by many names such as “Indian Bridge” and “town of St. Michael” throughout its history as an important center of inter-island trading. Thanks to its rich history, Bridgetown and its nearby Garrison are recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. As you explore this beautiful island, do not miss St. Mary’s Church, the second oldest consecrated ground on the island, or the Careenage, which was once a port for ships and now houses restaurants and boutiques. Spend some times exploring the wonders of the neo-gothic Parliament Building, which is open to the public when parliament is in session. Perhaps you would like to observe the natural beauty of Barbados and wander to Harrison’s Cave, a natural wonder of Barbados with its crystal clear pools of water and speleothems which adorn the cave, or give surfing a whirl. Whatever you choose, you are sure to enjoy the beauty that is Bridgetown. Suggested short-cuts to simple planning: The following trips are grouped according to interest categories. Cultural highlights: Nature and the Outdoors: Day 1: BAR 103-101 Walk Bridgetown Day 1: BAR 101-101 Barbados in Bloom Day 3: BAR 111-301 Colleton & St. Nicholas Abbey Day 2: BAR 106-201 Harrison’s Cave Day 3: BAR 110-301 Scenic Hike & Trail Barbados Action/Adventure: Day 1: BAR 102-101 Barbados Concorde Experience Historical Perspective: Day 2: BAR 108-201 Surfing Lesson Day 2: BAR 109-201 Heritage Trail: Slave Route Day 3: BAR 112-301 Aerial Trek Zipline TERMS AND CONDITIONS: In selling tickets or otherwise making arrangements for field programs (including transportation, shore side accommodations and meals); the Institute of Shipboard Education (I.S.E.) acts only as an agent for others who provide such services as independent contractors. -

Bridgetown, Barbados. Dec 2018

ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES Inter-American Council for Integral Development (CIDI) XX INTER-AMERICAN CONFERENCE OF OEA/Ser.K/XII.20.1 MINISTERS OF LABOR (IACML) CIDI/TRABAJO/doc.23/17 December 7 and 8, 2017 27 Febrero 2018 Bridgetown, Barbados Original: Spanish FINAL REPORT XX INTER-AMERICAN CONFERENCE OF MINISTERS OF LABOR OF THE ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES 17th Street and Constitution Avenue, NW, Washington, D.C. 20006 INDEX I. Background ...………………………………………………………….….….……....... 1 II. Proceedings ……...…………………………………………………….….….………... 1 A. Preparatory Meeting ………………………………..…………….….……………. 1 B. Inaugural Session ………………………………….…………….….…………….. 2 C. First Plenary Session ………………………………..…………….………...…….. 4 D. Second Plenary Session ……………………….……………………….……......... 5 E. Third Plenary Session ……………………………….……………….….…..…..... 8 F. Fourth Plenary Session ……………………………………………………...……. 9 G. Fifth Plenary Session ………………………………………….…………..…….. 10 H. Closing Session …………………………………...…………….……….……..... 13 ANNEXES APPENDIX I – RESOLUTIONS Declaration of Bridgetown 2017 ………………………………………………………… 17 Plan of Action of Bridgetown 2017 ……………………………………………………… 25 Resolution 1: Vote of Thanks to the People and Government of Barbados …...………… 33 Declaration of COSATE to the XX IACML ………………………………………….…. 35 Declaration of CEATAL to the XX IACML …………………………………………….. 43 Joint declaration of COSATE and CEATAL to the XX IACML ………………………... 45 APPENDIX II – REPORTS PRESENTED TO THE CONFERENCE Final Report of Working Group 1 …………………………..……………….…………… 49 Final Report of Working Group -

Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará

Water, Water Everywhere: Sea Level Rise and Land Use Planning in Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, and Pará Thomas E. Bassett and Gregory R. Scruggs © 2013 Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper The findings and conclusions of this Working Paper reflect the views of the author(s) and have not been subject to a detailed review by the staff of the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Contact the Lincoln Institute with questions or requests for permission to reprint this paper. [email protected] Lincoln Institute Product Code: WP13TB1 Abstract The Caribbean and northern coastal Brazil face severe impacts from climate change, particularly from sea-level rise. This paper analyses current land use and development policies in three Caribbean locations and one at the mouth of the Amazon River to determine if these policies are sufficient to protect economic, natural, and population resources based on current projections of urbanization and sea-level rise. Where policies are not deemed sufficient, the authors will address the question of how land use and infrastructure policies could be adjusted to most cost- effectively mitigate the negative impacts of climate change on the economies and urban populations. Keywords: sea-level rise, land use planning, coastal development, Barbados, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, Pará, Brazil About the Authors Thomas E. Bassett is a senior program associate at the American Planning Association. He works on the Energy and Climate Partnership of the Americas grant from the U.S. Department of State as well as the domestic Community Assistance Program. Thomas E. Bassett 1030 15th Street NW Suite 750W Washington, DC 20005 Phone: 202-349-1028 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Gregory R. -

North Atlantic Caribbean Basin

NORTH ATLANTIC CARIBBEAN BASIN NEWARK | BROOKLYN BARGE SERVICE* Brooklyn, New York Red HookCon-Ro Terminal Carrier Container Yard Port Newark, New Jersey Newark, NJ Philadelphia, Pennsylvania ATLANTIC OCEAN Red Hook Port Everglades, Florida Container Terminal PortMiami, Brooklyn, NY Florida Barge Cut-Off to Brooklyn, NY - 3:30PM GULF OF MEXICO Puerto Plata, Rio Haina, Dom. Rep. Barge Cut-Off to Newark, NJ - 3:30PM Dom. Rep. George Town, Grand Cayman Philipsburg, St. Marteen Basseterre, St. Kitts Montego Bay, Jamaica St Johns, Antigua Port Lafito, Haiti Bridgetown, Kingston, Jamaica Barbados FREQUENCY Point Lisas, Oranjestad, Trinidad Weekly Aruba Willemstad, Curacao PACIFIC OCEAN Georgetown, Paramaribo, Suriname Guyana Southbound SOUTHBOUND FROM BROOKLYN, NY DELIVERY TOTAL TRANSIT & NEWARK, NJ CUT OFF SAIL DAY ARRIVAL AVAILABLE TIME Delivery Cut Off from Newark, NJ Tuesday (3:30pm EST) To Kingston, Jamaica Tuesday Wednesday Monday Monday 5 Days To Rio Haina, Dominican Republic Tuesday Wednesday Tuesday Tuesday 6 Days To Montego Bay, Jamaica Tuesday Wednesday Tuesday Tuesday 6 Days To George Town, Grand Cayman Tuesday Wednesday Friday Friday 9 Days To Puerto Plata, Dominican Republic Tuesday Wednesday Sunday Monday 11 Days To Philipsburg, St. Maarten Tuesday Wednesday Sunday Monday 11 Days To Port Lafito, Haiti Tuesday Wednesday Monday Monday 12 Days To St. Johns, Antigua Tuesday Wednesday Monday Monday 12 Days To Basseterre, St. Kitts Tuesday Wednesday Monday Tuesday 12 Days To Point Lisas, Trinidad Tuesday Wednesday Tuesday Tuesday 13