The Odyssey – Guided Questions (Used for Class Discussions)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses

Intertextuality in James Joyce's Ulysses Assistant Teacher Haider Ghazi Jassim AL_Jaberi AL.Musawi University of Babylon College of Education Dept. of English Language and Literature [email protected] Abstract Technically accounting, Intertextuality designates the interdependence of a literary text on any literary one in structure, themes, imagery and so forth. As a matter of fact, the term is first coined by Julia Kristeva in 1966 whose contention was that a literary text is not an isolated entity but is made up of a mosaic of quotations, and that any text is the " absorption, and transformation of another"1.She defies traditional notions of the literary influence, saying that Intertextuality denotes a transposition of one or several sign systems into another or others. Transposition is a Freudian term, and Kristeva is pointing not merely to the way texts echo each other but to the way that discourses or sign systems are transposed into one another-so that meanings in one kind of discourses are heaped with meanings from another kind of discourse. It is a kind of "new articulation2". For kriszreve the idea is a part of a wider psychoanalytical theory which questions the stability of the subject, and her views about Intertextuality are very different from those of Roland North and others3. Besides, the term "Intertextuality" describes the reception process whereby in the mind of the reader texts already inculcated interact with the text currently being skimmed. Modern writers such as Canadian satirist W. P. Kinsella in The Grecian Urn4 and playwright Ann-Marie MacDonald in Goodnight Desdemona (Good Morning Juliet) have learned how to manipulate this phenomenon by deliberately and continually alluding to previous literary works well known to educated readers, namely John Keats's Ode on a Grecian Urn, and Shakespeare's tragedies Romeo and Juliet and Othello respectively. -

From the Odyssey, Part 1: the Adventures of Odysseus

from The Odyssey, Part 1: The Adventures of Odysseus Homer, translated by Robert Fitzgerald ANCHOR TEXT | EPIC POEM Archivart/Alamy Stock Photo Archivart/Alamy This version of the selection alternates original text The poet, Homer, begins his epic by asking a Muse1 to help him tell the story of with summarized passages. Odysseus. Odysseus, Homer says, is famous for fighting in the Trojan War and for Dotted lines appear next to surviving a difficult journey home from Troy.2 Odysseus saw many places and met many the summarized passages. people in his travels. He tried to return his shipmates safely to their families, but they 3 made the mistake of killing the cattle of Helios, for which they paid with their lives. NOTES Homer once again asks the Muse to help him tell the tale. The next section of the poem takes place 10 years after the Trojan War. Odysseus arrives in an island kingdom called Phaeacia, which is ruled by Alcinous. Alcinous asks Odysseus to tell him the story of his travels. I am Laertes’4 son, Odysseus. Men hold me formidable for guile5 in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca6 under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,7 loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea,8 the enchantress, desired me, and detained me in her hall. -

Not the Same Old Story: Dante's Re-Telling of the Odyssey

religions Article Not the Same Old Story: Dante’s Re-Telling of The Odyssey David W. Chapman English Department, Samford University, Birmingham, AL 35209, USA; [email protected] Received: 10 January 2019; Accepted: 6 March 2019; Published: 8 March 2019 Abstract: Dante’s Divine Comedy is frequently taught in core curriculum programs, but the mixture of classical and Christian symbols can be confusing to contemporary students. In teaching Dante, it is helpful for students to understand the concept of noumenal truth that underlies the symbol. In re-telling the Ulysses’ myth in Canto XXVI of The Inferno, Dante reveals that the details of the narrative are secondary to the spiritual truth he wishes to convey. Dante changes Ulysses’ quest for home and reunification with family in the Homeric account to a failed quest for knowledge without divine guidance that results in Ulysses’ destruction. Keywords: Dante Alighieri; The Divine Comedy; Homer; The Odyssey; Ulysses; core curriculum; noumena; symbolism; higher education; pedagogy When I began teaching Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 1990s as part of our new Cornerstone Curriculum, I had little experience in teaching classical texts. My graduate preparation had been primarily in rhetoric and modern British literature, neither of which included a study of Dante. Over the years, my appreciation of Dante has grown as I have guided, Vergil-like, our students through a reading of the text. And they, Dante-like, have sometimes found themselves lost in a strange wood of symbols and allegories that are remote from their educational background. What seems particularly inexplicable to them is the intermingling of actual historical characters and mythological figures. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated Lv Robert Fitzç’Erald

I The Odyssey Homer Translated lv Robert Fitzç’erald PART 1 FAR FROM HOME “I Am Odysseus” Odysseus is in the banquet hail of Alcinous (l-sin’o-s, King of Phaeacia (fë-a’sha), who helps him on his way after all his comrades have been killed and his last vessel de stroyed. Odysseus tells the story of his adventures thus far. ‘I am Laertes’ son, Odysseus. [aertes Ia Men hold me formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky’s rim. My home is on the peaked sea-mark of Ithaca 4 Ithaca ith’. k) ,in island oft under Mount Neion’s wind-blown robe of leaves, the west e ast it C reece. in sight of other islands—Dulichium, Same, wooded Zacynthus—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy’s training; I (I 488 An Epic Poem I shall not see on earth a place more dear, though I have been detained long by Calypso,’ 12. Calypso k1ip’sö). loveliest among goddesses, who held me in her smooth caves, to be her heart’s delight, as Circe of Aeaea, the enchantress, 15 15. Circe (sür’së) of Aeaea e’e-). desired me, and detained me in her hail. But in my heart I never gave consent. Where shall a man find sweetness to surpass his OWfl home and his parents? In far lands he shall not, though he find a house of gold. -

The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald

The Wanderings of Odysseus from The Odyssey Homer Translated by Robert Fitzgerald Book Nine: new Coasts and poseidon’s son ―What shall I say first? What shall I keep until the end? What conflict is introduced in Odysseus’ initial statements at the banquet? The gods have tried1 me in a thousands ways. What do these statements indicate about the kind of journey he has had? But first my name: Let that be known to you, 5 and if I pull away from pitiless death, friendship will bind us, though my land lies far. Now this was the reply Odysseus made: . ―I am Laertes‘ son, Odysseus. How are Odysseus’ comments about himself during his speech at Men hold2 me Alcinous’ banquet appropriate for an epic hero? formidable for guile in peace and war: this fame has gone abroad to the sky‘s rim. 10 My home is on the peaked seamark of Ithaca under Mount Neion‘s windblown robe of leaves, in sight of other islands—Doulikhion, Same, wooded Zakynthos—Ithaca being most lofty in that coastal sea, 15 and northwest, while the rest lie east and south. A rocky isle, but good for a boy‘s training; I shall not see on earth a place more dear, Odysseus refers to two beautiful goddesses, Calypso and Circe, who have though I have been detained long by Calypso, delayed him on their islands. (Details about Circe appear in Book 10.) loveliest among goddesses, who held me Notice, however, that Odysseus seems nostalgic for his own family and 20 in her smooth caves, to be her heart‘s delight, homeland. -

Myths and Legends: Odysseus and His Odyssey, the Short Version by Caroline H

Myths and Legends: Odysseus and his odyssey, the short version By Caroline H. Harding and Samuel B. Harding, adapted by Newsela staff on 01.10.17 Word Count 1,415 Level 1030L Escaping from the island of the Cyclopes — one-eyed, ill-tempered giants — the hero Odysseus calls back to the shore, taunting the Cyclops Polyphemus, who heaves a boulder at the ship. Painting by Arnold Böcklin in 1896. SECOND: A drawing of a cyclops, courtesy of CSA Images/B&W Engrave Ink Collection and Getty Images. Greek mythology began thousands of years ago because there was a need to explain natural events, disasters, and events in history. Myths were created about gods and goddesses who had supernatural powers, human feelings and looked human. These ideas were passed down in beliefs and stories. The following stories are about Odysseus, the son of the king of the Greek island of Ithaca and a hero, who was described to be as wise as Zeus, king of the gods. For 10 years, the Greek army battled the Trojans in the walled city of Troy, but could not get over, under or through the walls that protected it. Finally, Odysseus came up with the idea of a large hollow, wooden horse, that would be filled with Greek soldiers. The people of Troy woke one morning and found that no army surrounded the city, so they thought the enemy had returned to their ships and were finally sailing back to Greece. A great horse had been left This article is available at 5 reading levels at https://newsela.com. -

The Cyclops in the Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts

THE CYCLOPS IN THE ODYSSEY, ULYSSES, AND ASTERIOS POLYP: HOW ALLUSIONS AFFECT MODERN NARRATIVES AND THEIR HYPOTEXTS by DELLEN N. MILLER A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts December 2016 An Abstract of the Thesis of Dellen N. Miller for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of English to be taken December 2016 Title: The Cyclops in The Odyssey, Ulysses, and Asterios Polyp: How Allusions Affect Modern Narratives and Their Hypotexts Approved: _________________________________________ Paul Peppis The Odyssey circulates throughout Western society due to its foundation of Western literature. The epic poem thrives not only through new editions and translations but also through allusions from other works. Texts incorporate allusions to add meaning to modern narratives, but allusions also complicate the original text. By tying two stories together, allusion preserves historical works and places them in conversation with modern literature. Ulysses and Asterios Polyp demonstrate the prevalence of allusions in books and comic books. Through allusions to both Polyphemus and Odysseus, Joyce and Mazzucchelli provide new ways to read both their characters and the ancient Greek characters they allude to. ii Acknowledgements I would like to sincerely thank Professors Peppis, Fickle, and Bishop for your wonderful insight and assistance with my thesis. Thank you for your engaging courses and enthusiastic approaches to close reading literature and graphic literature. I am honored that I may discuss Ulysses and Asterios Polyp under the close reading practices you helped me develop. -

(2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. in A. Kampakoglou, & A

Finglass, P. J. (2018). Gazing at Helen with Stesichorus. In A. Kampakoglou, & A. Novokhatko (Eds.), Gaze, Vision, and Visuality in Ancient Greek Literature (pp. 140–159). (Trends in Classics Supplements; Vol. 54). Walter de Gruyter GmbH. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110571288-007 Peer reviewed version License (if available): CC BY-NC-ND Link to published version (if available): 10.1515/9783110571288-007 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via De Gruyter at DOI 10.1515/9783110571288-007. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ GAZING AT HELEN WITH STESICHORUS P. J. Finglass οἳ δ’ ὡς οὖν εἴδονθ’ Ἑλένην ἐπὶ πύργον ἰοῦσαν, 155 ἦκα πρὸς ἀλλήλους ἔπεα πτερόεντ’ ἀγόρευον· οὐ νέμεσις Τρῶας καὶ ἐϋκνήμιδας Ἀχαιοὺς τοιῆιδ’ ἀμφὶ γυναικὶ πολὺν χρόνον ἄλγεα πάσχειν· αἰνῶς ἀθανάτηισι θεῆις εἰς ὦπα ἔοικεν· ἀλλὰ καὶ ὧς τοίη περ ἐοῦσ’ ἐν νηυσὶ νεέσθω, 160 μηδ’ ἡμῖν τεκέεσσί τ’ ὀπίσσω πῆμα λίποιτο. Hom. Il. 3.154-60 When they saw Helen on her way to the tower, they began to speak winged words quietly to each other. ‘It is no cause for anger that the Trojans and well-greaved Achaeans should long suffer pains on behalf of such a woman. -

THE CYCLOPS) PHILOSOPHY on First Glance, This Story Appears to Be the Least Yielding When It Comes to Finding Philosophy for Discussion

NOBODY'S HOME (THE CYCLOPS) PHILOSOPHY On first glance, this story appears to be the least yielding when it comes to finding philosophy for discussion. But take a closer look and the philosophy starts to materialise from nothing. I say 'materialise from nothing' because I have found the most successful philosophical discussion emerging from this session to be about non-existent entities. This topic emerges from both the content of the story (i.e. his use of the word 'nobody' to trick the Cyclops – 'nobody' seeming to be a referring term for someone that isn't there) and a feature of the story (i.e. that it contains a famous mythical creature – mythical creatures being perfect examples of non-existent entities). So, how can something that doesn't exist have certain qualities or features? Does our collective reference to a Cyclops somehow give it existence, perhaps in our minds, in our culture, or in some other way? Some philosophers have thought so. If so, what kind of existence would this be? It's certainly not the kind of existence something like a rabbit has. Or is it simply that a Cyclops does not exist in any way? But if this is the case, how can you meaningfully speak about one - how can you tell the story you are about to tell? Note: this story contains a clear example of a key Ancient Greek theme and one that runs throughout the Odyssey: hubris, 'downfall brought about by excessive pride'. Odysseus' announcement revealing his true identity to Polyphemus from the prow of his ship endangers both himself and his crew by inciting the wrath of the god Poseidon no less. -

Back-To-Back Synopses.Indd

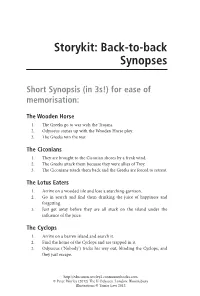

Storykit: Back-to-back Synopses Short Synopsis (in 3s!) for ease of memorisation: The Wooden Horse 1. The Greeks go to war with the Trojans. 2. Odysseus comes up with the Wooden Horse ploy. 3. The Greeks win the war. The Ciconians 1. They are brought to the Ciconian shores by a freak wind. 2. The Greeks attack them because they were allies of Troy. 3. The Ciconians attack them back and the Greeks are forced to retreat. The Lotus Eaters 1. Arrive on a wooded isle and lose a searching-garrison. 2. Go in search and find them drinking the juice of happiness and forgetting. 3. Just get away before they are all stuck on the island under the influence of the juice. The Cyclops 1. Arrive on a barren island and search it. 2. Find the home of the Cyclops and are trapped in it. 3. Odysseus (‘Nobody’) tricks his way out, blinding the Cyclops, and they just escape. http://education.worley2.continuumbooks.com © Peter Worley (2012) The If Odyseey. London: Bloomsbury Illustrations © Tamar Levi 2012 Aeolus 1. Arrive on a fortified island and are finally welcomed as guests. 2. Odysseus is given a bag as a gift by Aeolus. 3. Crew mutiny just as they reach home and release the winds from inside the bag, blowing them back out to sea. The Laestrygonians 1. Arrive on another island with an encircled harbour. 2. Find out the hard way that this is an island of giant cannibals. 3. They only just escaped with their lives. Circe 1. Arrive on yet another island only for some of the men to be turned into pigs by the goddess Circe. -

EME Revisited – the Story of Odysseus Script by Olivia Armstrong – April 8Th 2020

EME Revisited – The Story of Odysseus Script by Olivia Armstrong – April 8th 2020 Introduction Hello. I am Olivia – I tell stories, Stories that are big and stories that are small. You can listen quietly or you can join in. If you are going to join in, there are some things you will need! Ordinary household things that should be easy to find. I am going to tell you what you need and then why don’t you pause the story while you and your grown-ups go and find them? Don’t worry if you don’t have everything on the list. Whatever you have, there will still be plenty for you to join in with. Are you ready to write these down? Okay – number one – a handful of uncooked rice emptied onto a baking tray. Two – a sheet, or a piece of cloth. Three – some torn up paper or newspaper in a plastic bag. Three – a piece of tin foil. Four – a small piece of fruit or your favourite snack. Five – a cushion or pillow. Six – a couple of sticks of raw celery and a few strands of uncooked spaghetti. Seven – a small handful of cooked pasta in a bowl. And eight – any shakers or drums or bells you might have. Go and gather those things now. Don’t forget to pause the story! [ Pause here while you collect props ] Story begins Hello! Are you back? Lay all the things out in front of you, within easy reach. Your grown can help you keep everything tidy! One of my favourite places to tell stories is the magical British Museum. -

Story 1: the Cicones

THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 STORY 1: THE CICONES THE WANDERINGS OF ODYSSEUS – STORIES 1-11 (OF 30) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 THE CICONES SHIP AND CREW COUNT BEFORE AFTER 12 Ships 12 Ships 608 Men 536 Men After ten long years, the Trojan War is over. The ACHAEANS (a name for the Greeks) have defeated the Trojans. ODYSSEUS, his men, and their twelve ships, begin their journey home to ITHACA. The storm winds take them to the land of the CICONES where Odysseus and his men sack the main city Ismarus, attack their people, and steal their possessions. Odysseus and each of his men share the stolen riches equally. Odysseus urges that they leave. The crew do not listen. They slaughter the Cicones’ sheep and cattle, and drink their wine. The Cicones call for help. Now stronger and larger in number, the Cicones fight back with force. Odysseus loses six men from each of his twelve ships. He feels he and his men are being punished by ZEUS. Odysseus and the rest of his crew sail away before any more men are killed. BOOK AND LINE REFERENCES BOOK 9 (OF 24) Fagles (Fa) Fitzgerald (Fi) Lattimore (La) Lombardo (Lo) 9.44-75 9.43-73 9.39-66 9.42-68 NOTE: The numbers appearing after the Book Number (in this case, Book 9) are the specific line numbers for each translation. Although Book Numbers are the same across all four translations, line numbers are not. If you are using a prose translation (and line numbers aren’t provided), use the Book references provided above; the line numbers can be used to provide an approximate location in that Book for the particular passages.